Major League Baseball’s regular season ends one month from Friday, and MLB’s best records belong to the Milwaukee Brewers and Toronto Blue Jays.

This is surprising on multiple levels. For one, few foresaw league-leading win totals for Milwaukee or Toronto. FanGraphs gave them the 19th-highest and 15th-highest preseason win total projections, respectively. Baseball Prospectus pegged them 19th and 14th. The sportsbooks were less optimistic. And none of the 59 expert prognosticators at MLB.com, the 33 at The Athletic, or the 28 at ESPN picked the Brewers or Blue Jays as a pennant winner. These weren’t expected to be bad teams, but both seemed destined to be mid.

But forget about five months ago. If someone with no knowledge of the present standings were to scan the stat lines on the two teams’ rosters, it would be difficult to identify the Brewers and Jays as MLB’s winningest teams today. The only black ink (to denote a league leader) on the Brewers’ Baseball Reference page comes from Freddy Peralta’s major league–leading 15 pitcher wins; on the Jays’ page, bold text distinguishes Bo Bichette’s MLB-best hits and AL-best at-bats totals, Chris Bassitt’s AL-leading hits allowed total, and reliever Brendon Little’s AL-high appearances count. No Brewers hitter or Blue Jays pitcher made the All-Star team; 14 teams tied or surpassed the Brewers’ tally of three representatives (including, controversially, flamethrowing phenom Jacob Misiorowski), and 21 tied or surpassed Toronto’s two. By FanGraphs WAR, the Blue Jays’ most valuable player (Alejandro Kirk) ranks 37th overall; the Brewers’ (Brice Turang), 50th. Twenty-one teams have a better “best” player than the Jays, and 23 have a better “best” player than the Brewers.

So how have the 83-52 Brewers and 78-56 Blue Jays, who face off on Friday for the first time this year, topped all other teams to date? The answer is almost the same for each club. Both have excelled in several non-flashy respects that have made their records more impressive than the sum of their parts. As their Spider-Man-meme, mirror-image seasons intersect in Toronto, let’s tick off the fantastic four factors that have helped propel Milwaukee and Toronto to the top seeds in the sport despite modest (at most) expectations and a dearth of individual spectacular campaigns.

They’ve been deep

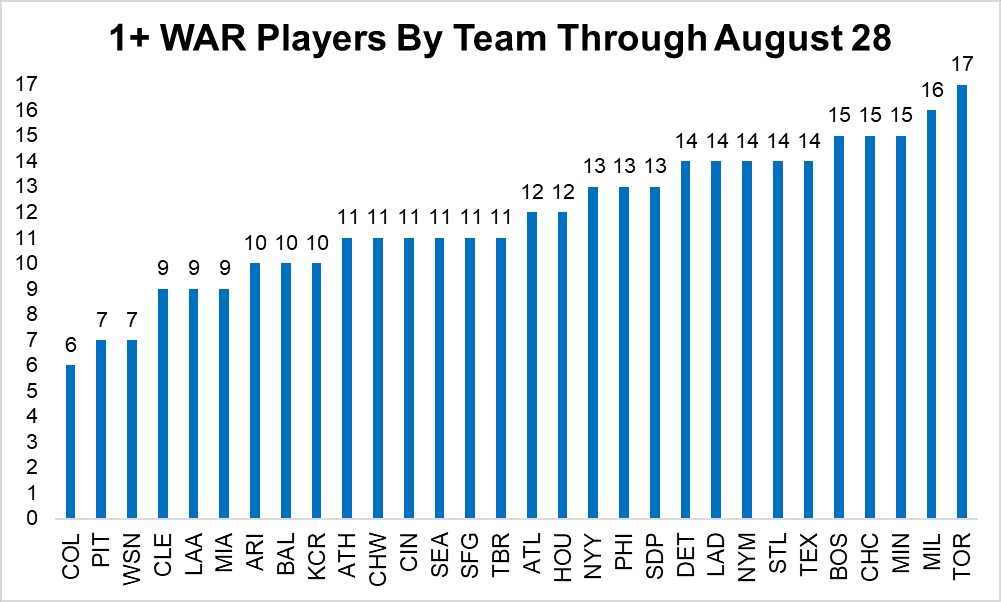

What the Brewers and Blue Jays lack in quality toward the top of the WAR leaderboard, they make up in quantity a little lower down. The two teams feature few stars—or at least few players having star-level seasons—but they aren’t saddled with scrubs, either. Despite the absence of high-end, MVP/Cy Young–caliber talent, they’re third and seventh, respectively, in overall WAR. (If you’re wondering how these teams have won the most games without the most WAR, keep reading.) And that’s because they’re second and first, respectively, in players with at least 1 WAR. Essentially, their list of useful options is longer than anyone else’s. Their rosters have low ceilings, but high floors.

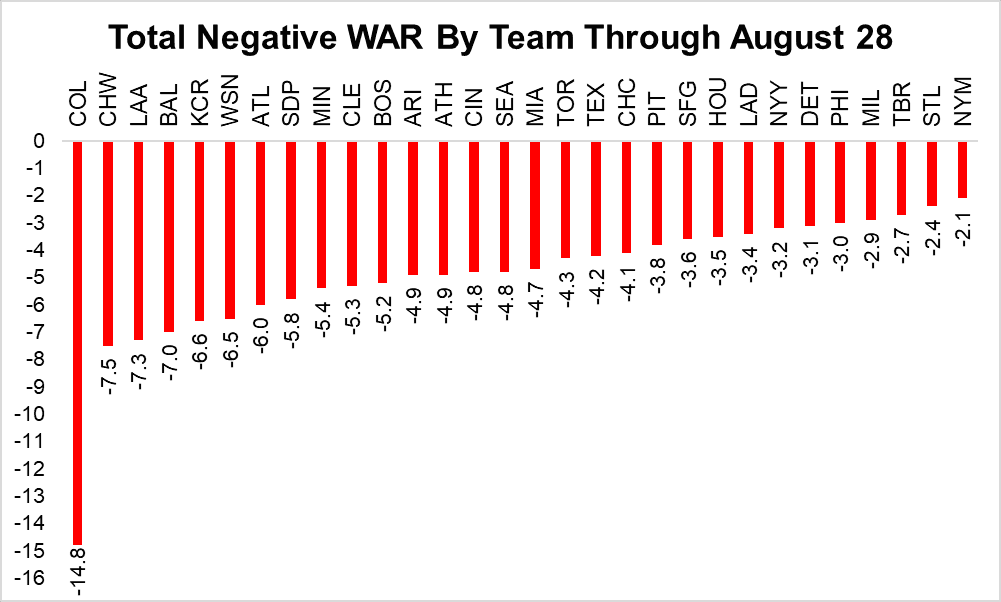

Thanks to that long tail of competent players, the Brewers, especially, have managed to “avoid the awful,” in the parlance of former FanGraphs writer Jeff Sullivan. Only three other teams have collectively compiled less negative WAR than Milwaukee. That kind of depth pays dividends: Stars are sexy, but avoiding sub-replacement-level players is important, too.

Much has been written about how the Brewers were built. Their roster boasts a bit of everything: first-round draftees (Sal Frelick, Turang); failed-prospect castoffs from other teams who’ve broken out as Brewers (Andrew Vaughn, Quinn Priester); trade steals (Peralta, Christian Yelich, William Contreras); even a minor league Rule 5 pick plucked from the Rockies (one of Milwaukee’s several Rookie of the Year contenders, Isaac Collins). The Brewers have traded and developed their way to a robust roster, and they’ve done it largely by identifying external talent. FanGraphs’ Roster Resource classifies only six players on the Brewers’ 26-man roster as “homegrown.” In that, they’re like the Jays, who have five homegrown guys. Only the Padres, built by A.J. Preller’s prolific dealmaking, have fewer (three).

They’ve gotten on base

The Brewers and Blue Jays score runs: They rank third and sixth, respectively, in the runs column despite neutral to negative park factors. However, they don’t drive the ball. The Blue Jays and Brew Crew rank 12th and 19th, respectively, in home runs; 12th and 20th in isolated power; 12th and 28th in average exit velocity; 12th and 25th in hard-hit rate; 15th and dead last in barrel rate, and 19th and 28th in percentage of batted balls that are pulled in the air. Pitchers apparently aren’t afraid of Brewers batters, who see pitches in the strike zone at the highest rate of any team (and chase pitches outside the zone at the lowest rate).

In a league that’s hyper-focused on punishing pitches, these clubs’ somewhat soft contact doesn’t stand out (or does stand out, but for the wrong reasons). On the plus side, they rank first and second in on-base percentage. Neither team parts lightly with outs, the main currency of the sport.

Even in this area, they’re a tad out of step with the times: Their on-base ability comes not so much from walking as from making contact and posting similarly lofty batting averages (by the era’s low-average standards). The Jays lead the sport in singles; the Brewers, who beat out grounders and rack up infield hits, rank a close second. Consequently, they rank 21st and 28th in percentage of runs scored on homers, according to Baseball Prospectus. They may deal death by a thousand cuts, rather than by big blows, but their lineups have been lethal nonetheless.

They’ve been clutch

Adept as the Brewers and Blue Jays have been with the bats, they’ve still scored more runs than one would expect based on their slash stats. That’s because they’ve clustered their best play at opportune times, on both sides of the ball. Blue Jays and Brewers batters rank second and eighth, respectively, in FanGraphs’ “Clutch” metric, which compares performance in high-leverage situations to overall performance. The two teams’ pitchers place in the top 10 in that statistic, too. And if you prefer to assess production with runners in scoring position relative to overall production, well, Brewers and Blue Jays batters are top 10 in that also (and their pitching staffs are both better than average).

Put it all together, and the Brewers have scored about 40 more runs than they “should” have, and allowed about 12 fewer. Typically, this kind of clutchness isn’t repeatable, though Brewers batters have been clutch in every season since 2020 (a streak that has already reached historic proportions). Call it clutchness, luck, or good timing, but Milwaukee and Toronto have raised their games when it’s mattered most.

The two clubs have also picked their spots effectively in a second sense: They’ve excelled in games decided by one run, which tend to be heavily luck dependent. The Jays are 23-15 in such contests, while the Brewers are 26-17. As a result, Toronto and Milwaukee have exceeded their deserved/expected win records, as determined by a BaseRuns accounting of their underlying performance, by five and four wins, respectively, more than any other club besides the Guardians, Astros, and Angels. Hence the slight mismatches between their overall records and their players’ context-neutral numbers.

They’ve played good defense

Fielding is the silent killer of other teams’ dreams. Even with plenty of fancy fielding stats at our disposal, defense tends to be a little less salient than raking in the batter’s box or shoving on the bump. And although the Brewers and Blue Jays aren’t elite teams on the mound, they’ve got great gloves, which can compensate for other flaws in their run prevention. Per Statcast, only the Cubs have accrued more fielding value than the Blue Jays and Brewers. Other defensive stats that fold in fielder positioning suggest that Toronto’s and Milwaukee’s defenses are merely very good, not great, but this is still a strength that’s easily overlooked unless you’re looking at particular leaderboards.

If anything, the Jays—whose fielders led the majors in multiple metrics last season—have underperformed their potential in the field: Reigning Gold Glovers Daulton Varsho and Andrés Giménez have missed much of the season with injuries. As it is, their defensive value is heavily concentrated at catcher—thanks, Alejandro Kirk—whereas the Brewers have been above average almost everywhere. But both of these clubs can pick it, and that pays off.

There are plenty of parallels between the Brewers and Blue Jays, but they aren’t identical-twin teams. The Brewers, newly anointed poster team for the fundamentals, are baseball’s best baserunning club; the Jays are one of the worst. (Toronto has grounded into the majors’ most double plays, whereas Milwaukee, which has encountered the majors’ most double-play opportunities, has grounded into the third-fewest.) The small-market Brewers rank 22nd in player payroll, while the Blue Jays just crack the top five. Relatedly, the youthful Brewers, who’ve rebuilt their roster without missing a beat, pace the pack in WAR produced by players 25 and younger, while the Jays, whose entire rotation has seen the last of its 20s (or in Max Scherzer’s case, 30s) trail only Texas in WAR from players 34 or older. (The Brewers also have a higher-rated farm system, despite their recent graduations, which bodes well for their future.)

Moreover, none of the above necessarily suggests that the Brewers and Blue Jays have hacked baseball long term, or even that they’ll sustain their success this season. FanGraphs ranks Milwaukee and Toronto 12th and 10th in rest-of-season winning percentage, suggesting that numbers-based evaluation methods still aren’t sold on the clubs as the cream of the crop. And though Milwaukee has a slightly more comfortable cushion, it wouldn’t take much for Toronto to lose its grasp on baseball’s second-best record: The Tigers trail the Jays by half a game, and in the NL, two predicted powerhouses, the Dodgers and Phillies, lag a game behind. The sport’s post-superteam interregnum has made it more feasible for two surprise teams to vault to the top of the standings. (If not for Milwaukee, MLB would be on pace for its first season since 2013 in which no club posted a .600 winning percentage.) But it’s also compressed the standings such that there’s little separation between the “best” and next-best teams.

Of course, the Brewers and Jays won’t be judged by the regular season alone. The Brewers haven’t won a playoff round since 2018, and the Jays haven’t won a playoff game since 2016. To pull back a bit, 23 franchises have won a pennant since the Blue Jays’ last trip to the Fall Classic in 1993, and the Mariners and Pirates are the only other two teams without a World Series appearance since the Brewers’ last (and lone) league title in 1982. The Brewers and Blue Jays have beaten the odds just by being baseball’s biggest winners well into the final fifth of the regular season, which has put them in strong playoff position. But October is the month when they’d most like to prove the experts and projections wrong.

Perhaps Friday’s Peralta vs. Shane Bieber battle, Saturday’s Priester vs. Kevin Gausman matchup, and Sunday’s Brandon Woodruff vs. Scherzer showdown will serve as postseason previews. This weekend’s series is the only scheduled clash between the Brewers and Blue Jays in 2025. But they’d both sign up for four more matchups, minimum, this fall.