C.J. Stroud loves football. Most quarterbacks do, but for the 23-year-old Houston Texans passer, it’s bordering on obsession. When Stroud isn’t playing football, he’s often found talking about it. Stroud picked up an offseason side job as an analyst … the summer after being named Offensive Rookie of the Year. He served as a guest on Bleacher Report’s live draft show in 2024, a stream that lasted more than four hours. Even near the end of the marathon broadcast, Stroud was still offering up informed takes on prospects that most football fans had probably never heard of. Throughout the 2024 offseason, you could also find him getting into heated debates with Micah Parsons, singing the praises of his favorite underappreciated quarterback, or breaking down his own film with impressive clarity. Stroud doesn’t just love the sport; he knows it inside and out.

Both Texans offensive coordinator Nick Caley and quarterbacks coach Jerrod Johnson say that Stroud’s football obsession makes their respective jobs a lot easier. They don’t need to push the QB to prepare harder or watch more film; he does that on his own. “He studies ball,” Caley told me recently on a cold and gloomy day in West Virginia, where the Texans held a week of training camp practices. “C.J. studies the league. I mean, he watches. It’s amazing how much tape he watches.”

Caley says that he picked up on his quarterback’s passion for the sport in their first interaction, an hours-long conversation back in the spring. Caley was hired away from the Rams in February and says that he and Stroud have hit it off quickly, even though they have two very different personalities. Stroud is laid-back—even when arguing with Parsons on a podcast, the quarterback never seemed too worked up—while Caley is all energy. You wouldn’t need to know that he spent the past two years in L.A. to recognize Sean McVay’s influence on his coaching style. Get him some blond hair dye and a more form-fitting shirt, and Caley could pass for his former boss.

“They talk the same,” Stroud joked of Caley and McVay. “They have the same tone of voice, which is kind of funny. Cales is a little turned up. Well, not a little. He’s turned up to the max. And I’m more of a chill guy, at least on the field. … It’s yin and yang.”

Caley said that he and C.J. “might have different personalities, per se, but it's fun to be around people that share a common interest, and I love working with him.”

The feeling is mutual. “I’m excited to work with him,” Stroud said of his first-year play caller following a preseason win against the Panthers. “He’s a great guy, loves football, knows football, knows why we’re calling things, how to call them, when to call them. He’s been great, and I’m very grateful to have him as an OC.”

The two also share a common goal: fixing the Texans offense, which broke in a number of ways during the 2024 season. Issues in protection, pre-snap penalties, and injuries to key skill players derailed a promising start, and the previous offensive coaching staff proved incapable of getting the unit back on track. Collectively, that created an unsuitable environment for Stroud to build on the successful rookie campaign he had in 2023. His numbers regressed across the board. After ranking in the top 10 in yards per dropback, EPA per dropback, and success rate in 2023, he slid toward the bottom of the league in those metrics during his sophomore season.

C.J. Stroud, 2023 Season vs. 2024 Season (TruMedia)

Stroud was far from perfect in 2024, but he didn’t perform as poorly as those numbers imply. Plus, he had arguably the highest degree of difficulty faced by any quarterback in the league. No passer faced more unblocked pressures (79), according to Pro Football Focus. That, in combination with the Texans’ impotent run game, led him to face a lot of tricky situations. He finished second in the NFL in dropbacks on third-and-10-plus, per TruMedia.

“He was put in some adverse situations [last season],” Johnson told me. “But our job as quarterbacks is to find solutions. We always take the mindset, What can we do to help? … I’m looking to get more easy downs for him. With that being said, one thing is guaranteed out there on Sunday: Something’s going to come up, and it’s our job to find the answer.”

Texans head coach DeMeco Ryans believes that Caley will help Stroud find those answers and get Houston “over the hump” after two straight seasons that ended with divisional-round playoff losses. During Caley’s introductory press conference in February, Ryans identified the team’s issues in pass protection as an area that needs drastic improvement this year.

Typically, when a young quarterback struggles through a tough season, the solution isn’t to put even more on his plate. But that’s exactly what the Texans are doing in 2025. Stroud asked for more ownership of the offense after last season’s disappointing results, and Ryans and Caley are giving it to him. For the first time in his NFL career, Stroud will be able to change protections and call audibles before the snap. Houston will be leaning on Stroud’s knowledge and feel for the game in ways it didn’t over the past two years. It’s the type of control that the best quarterbacks across the league enjoy—from Patrick Mahomes in Kansas City to Joe Burrow in Cincinnati. But with that comes another layer of pressure for Stroud.

“I don’t want to say it lights a fire under [quarterbacks],” Texans tight end Dalton Schultz told me during a post-practice chat. “But it’s like, Hey, you better be on your shit. You omit one word from the play call, now everything’s messed up. It puts a little more pressure [on him] in that sense. But at the same time, with responsibility comes a lot of freedom—the feeling that you can put your own twist on it.”

As Stroud will point out, this autonomy may be a new feature of the Texans offense, but it’s not entirely new to him. “It’s like what I’ve done in the past,” Stroud said after Saturday’s preseason win over Carolina. “Like high school, I had a lot of other ways to get to plays, protections. Same thing in college. Our schemes the last two years really didn’t have those capabilities—at least not yet—so I really didn’t get to do it. But this year we’ve introduced that, and I think it’s been great to just have some ownership, know what’s going on, not always have to throw hot [with] all these guys in my face.”

Stroud played under offensive coordinator Bobby Slowik in his first two professional seasons. Slowik had previously worked as an assistant under Kyle Shanahan in San Francisco and brought his own version of the famed Shanahan offense with him to Houston. The results were mixed. While Shanahan’s schematic guardrails eased Stroud’s transition to the pros, the offense failed to evolve in year two. The Shanahan system is great for young quarterbacks because it limits the thinking they have to do before the snap. As long as the quarterback reads the play out, exactly as the coach has laid it out, the offensive design will have answers to any problem the defense could present—even if those answers aren’t ideal.

“I believe in playing fast and not having to get up there and sit at the line forever and have to look at all these things and get yourself into the perfect play," Shanahan said in 2017, early in his tenure as 49ers head coach. "As a playcaller, I always try to call the perfect play … if it’s not the perfect play, there’s usually four other options that you’ve just got to adjust to and either get an incompletion or get a smaller gain. But, it’s not, ‘Hey, if I don’t call the perfect play, you check and get us into the perfect play.’ I’ve been in systems like that and it’s just what your opinion is and there’s really no right answer.”

The Shanahan system is popular for a reason. It works. We’ve seen it turn afterthought prospects (like Nick Mullens) into viable short-term starters and average quarterbacks (like Jimmy Garoppolo) into highly paid stars. But no system is perfect, and the Shanahan offense certainly has its flaws, which defenses were better able to expose in 2024. The pass protection system is probably the most glaring weakness. Instead of giving the quarterback freedom to redirect the protection before the snap to pick up pressure, Shanahan coaches expect their passers to find the “hot routes” in the play design. These are usually quick-hitting routes that the quarterback can target when the defense overloads the protection and gets a free rusher.

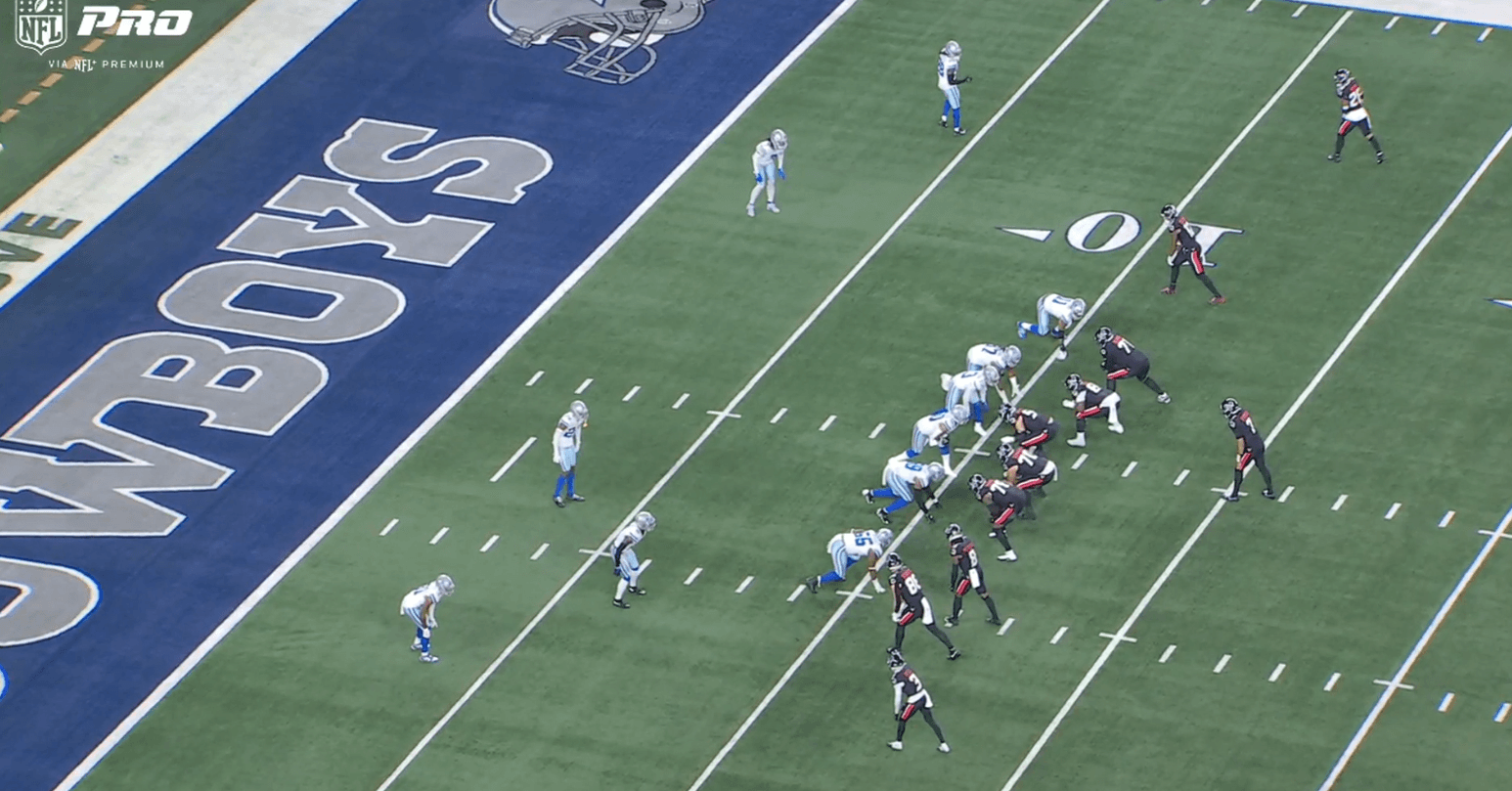

Earlier, I mentioned that Houston led the NFL in unblocked pressures allowed last season. Well, Shanahan’s 49ers finished in second. The Saints, who had former Shanahan assistant Klint Kubiak as their offensive coordinator, finished fourth in that metric. Mike McDaniel’s Dolphins finished just outside the top 10. The unblocked pressures aren’t necessarily a bug in the scheme; they’re a feature. Let’s look at an example of how this works—and why Stroud is excited that he won’t “always have to throw hot” this season. This play comes from Houston’s Week 11 win against the Cowboys last season. The Texans are lined up in an empty formation (with no running backs aligned in the backfield), and Dallas is in a clear blitz look with six defensive players on the line of scrimmage.

Houston is running a red zone staple of the Shanahan offense, a concept called “Pile,” to the top of the image. The inside receiver is running the “Pile” route, a 10-yard out, while the outside receiver is running a quick slant pattern. As you can see in the diagram below, from Shanahan’s 2018 playbook, both are considered “hot” options against all-out pressure.

There is a clear problem for the offense based on the pre-snap picture: The Cowboys are presenting more potential pass rushers (six) than the Texans have blockers (five). If all those rushers come after the quarterback, at least one of them will have a free path. Instead of shifting the protection or changing the play to bring another blocker in, Shanahan and Slowik want their quarterback to beat the rusher with a quick throw. But sometimes, that free rusher is Parsons, and what looks like a good idea on paper doesn’t work out on the field.

Even when it isn’t an All-Pro rusher bearing down on you, these throws can be difficult to pull off. Here’s Houston running the same play against an all-out blitz in a late-season game against the Chiefs. This time, Stroud fades back to try to hit the out-breaking route, but he has to throw it before his receiver comes out of his break.

In Caley’s system, Stroud would have the freedom to change the protection or check into a different play call that’s better against an all-out blitz. And Caley learned the value of putting the offense in his quarterback’s hands in New England, where he started his NFL coaching career during the last few years of the Tom Brady era. With the Patriots, Caley was mentored by famed offensive line coach Dante Scarnecchia, whose protection system afforded the quarterback a lot of freedom to make changes at the line of scrimmage. Here’s Bill O’Brien, who served as the Pats’ offensive coordinator in 2011, explaining how the system works, specifically when the offense is in an empty formation:

“When we describe this, we say, ‘It’s a five-man protection. It’s an automatic slide to the [weakside linebacker] unless you make certain calls to trump that. What we say to them is, ‘Is the [weakside linebacker] a threat when you get to the line of scrimmage?’”

If not, the quarterback can slide the protection the other way to pick up a potential blitz. Here’s an example of Brady doing just that in a 2018 game against the Jaguars. You can hear him shout “Rita” to his linemen, telling them to slide to their right.

The Jags send a blitz from that side, but Brady doesn’t have to worry about it and can work the other side of the field. In a Shanahan-style system, the quarterback would be instructed to throw “hot” to the right side, where Brady could have hit Rob Gronkowski on a short stop route, but the tight end would have been tackled for a short gain to bring up third-and-short. Instead, Brady worked the concept to the top of the screen and found a receiver for a first down. The offense stayed on the front foot rather than letting the defense dictate the terms of engagement.

That’s not to say that the Shanahan system is bad or that every team should be operating as if it has Brady under center. Just look at the results over the past few seasons: The Shanahan coaches are doing just fine, while coaches from the New England tree aren’t getting much work. There are pros and cons to every scheme, and how an offense should operate depends on what the quarterback can handle.

“There are some guys who play better when they can just get back and rip it,” Schultz, who’s played in both styles of offense throughout his NFL career, told me. “Some guys can just play faster the other way, so I think it would be unfair to say, ‘This [system] handicaps a quarterback more than another.’ It’s kind of dependent.”

But the Texans believe that in Stroud, they have a quarterback who can handle more of that mental load. And Stroud has looked the part during camp. On the second day of my visit to West Virginia, the team held what amounted to an intra-squad scrimmage. Up until that point, the defense's dominance had been a major talking point in camp, but Stroud had the offense moving in this practice. He was making changes at the line of scrimmage, redirecting the protection, and adjusting routes on the fly. That wasn’t a new development—Caley says that Stroud has consistently taken what he’s learned in meetings to the practice field—but it was the first real look at what this offense could be capable of with Stroud in control.

A scheme change won’t solve all of Houston’s problems from last season, and not all of the protection issues can be pinned on Slowik’s scheme. Even when the Texans had enough blockers to pick up the pass rush, it didn’t always happen. Seemingly every week, there were examples of offensive linemen sticking on blocks far too long while they let another defender run free at their quarterback. Houston was particularly bad when blocking against defensive line stunts, and Stroud was sacked a league-leading 20 times on those plays, per PFF. The Texans were constantly tinkering with their lineup last season, so offensive line cohesion was nonexistent—and it showed on the field. The Week 7 loss in Green Bay was a particularly brutal showing for the line, which gave up nine unblocked pressures against an average Packers front.

Some of those pressures were caused by a flawed protection call, but most of them could have been avoided with better teamwork. Caley hopes that installing Scarnecchia’s protection scheme in Houston will help simplify the assignments for his blockers.

“Dante is the master of making something that can be complicated at times very, very simple for the players,” Caley said. “He believed in being coordinated and seeing the game through the same set of eyes, so the quarterback, the backs, the tight ends are all in line and everybody is tied together.”

So far, so good, according to Schultz, who said that the protections have been the most significant change Caley’s brought to Houston. While the offensive line has had its struggles going up against the most disruptive pass rush in football every day in camp, that hasn’t been due to mental errors.

“It’s hard when you’re going against Will [Anderson] and [Danielle Hunter],” said Schultz. “It’s hard to protect even when your rules are right. Fuck, sometimes it feels like the world’s caving in every down. But the rules are very simple for guys, and it’s made it cleaner in terms of assignments. … Early on in a new scheme and a new system, that’s the most important thing.”

Stroud’s control over the offense isn’t limited to just pass protections. Schultz says that he has more responsibilities in the run game, too. He’ll make adjustments to blocking assignments depending on what he’s seeing from the defense. And if the defense is in a front the offensive line isn’t designed to block, it will be up to Stroud to get his team into a better play. Caley is placing the offense in the hands of his quarterback, who may be young but has experience and insight that the first-year play caller simply can’t provide.

“I’ve never played quarterback,” Caley said. “I’ve coached offense for well over a decade, but you learn things and see things from a quarterback’s perspective. … We [as coaches] can prepare all we want, but the pictures could change. That could be intentional from the defense, or it may be due to injuries and personnel. Now they’re working out of certain groupings, or they give you some abnormal fronts you didn’t expect. When you have a quarterback who understands the intent of what you’re doing, he can solve problems for you. He can get you out of bad situations and get you into favorable ones.”

With the added responsibility, Stroud’s job has gotten harder this offseason, but it’s a challenge his coaches are positive he’s ready to take on.

“My role as quarterback coach is to mentor quarterbacks,” Johnson said. “It’s our job to help them on their journey finding greatness, and I think C.J. wants to keep progressing in this league going into year three. And I think he’s at a place in his career where he can handle it. It is more challenging and it requires more preparation, but having more control should help him have more success.”

Stroud and the Texans aren’t just looking to bounce back after a frustrating year. They’re looking to take a step forward and establish themselves as challengers to the Chiefs, Bills, and Ravens at the top of the AFC. Stroud asked for ownership of the offense to help him compete with the MVP-winning quarterbacks who lead those teams. His coaches all agreed that it was a necessary step in his development and handed him the reins. What he does with them will determine how far he can take Houston this season—and whether he’ll make the leap to join the league’s class of elite quarterbacks in his third year.