Jon Turteltaub still remembers the first time he saw Jaws.

The director of National Treasure, Cool Runnings, and The Meg was 12 years old when the 1975 blockbuster came out. Back then, the summer was an unceremonious burial ground for lousy movies. So Turteltaub walked into the theater halfway through a screening and sat down. He wound up watching Jaws through to the end and then sticking around to see the entire thing from start to finish. He was glued to his seat, with one exception.

“Right after the shark popped up in the chumming sequence with Chief Brody [Roy Scheider], I went to the lobby to use the pay phone. I called my mother and told her I thought I was having a heart attack,” Turteltaub says. “I was serious. I was also an idiot. But I was completely overwhelmed by the entire experience.”

Not everyone remembers their first time seeing Jaws so vividly. The movie, which changed Hollywood forever in more ways than one, has been a part of our cultural fabric ever since. It invented the summer blockbuster, launched Steven Spielberg’s career (he was 26 when he directed the film), inspired a slew of sharksploitation imitators, and instilled a fear of the ocean in multiple generations of movie fans. If you’re not old enough to have seen Jaws in theaters, you probably absorbed it by osmosis, thanks to countless cable TV airings and pop culture references.

“Jaws has always been there, even though I cannot remember the first tasty bite,” says Sean Byrne, director of the 2025 shark thriller Dangerous Animals.

A half century after an oversized, mechanical great white shark stalked the inhabitants of Amity Island for our amusement, The Ringer hunted down a panel of filmmakers including Turtletaub and Byrne, along with the two screenwriters and director behind the Sharknado franchise (Thunder Levin, Scotty Mullen, and Anthony C. Ferrante, respectively) and the director of disaster epics San Andreas and Rampage (Brad Peyton) to unpack the many ways that Jaws continues to influence the movie industry all these years later.

One thing is clear: Jaws remains as relevant and influential as it was when it first came out.

“I’m not sure we’d have megaplexes and massive cinemas without that movie,” says Peyton, who’s made a career out of pitting Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson against everything from earthquakes to radioactive lizards.

Shot on a budget of $9 million (Spielberg quickly blew past his original $4 million allotment), Jaws was the first movie to earn $100 million at the U.S. box office, topping out at $477.9 million worldwide. It changed the entire calculus of moviemaking, showing Hollywood studios that a well-timed summer spectacle could make enough money to bankroll most of their annual business.

“It spawned the blockbuster mentality,” says Byrne.

Whether you view that as a good thing or a bad thing depends on your perspective. Not everyone is a fan of the summer movie season, when action movies and animated films clog up theaters and push out more serious films. Then again, it’s not like the alternative was much better.

“Before Jaws, the summers were filled with throw-away titles and kiddie films,” says Turteltaub. Not only did Spielberg raise the bar for summer releases, he also showed it’s possible to make a hit movie that appeals to everyone. “Kids can handle movies with adult themes, and adults can handle movies with kids' themes,” Turteltaub adds. “Steven bridged that gap.”

Beyond establishing the summer blockbuster, Jaws also invented new rules for horror filmmaking, while borrowing liberally from masters of tension-building like Alfred Hitchcock. Jaws might not fit our traditional definition of a scary movie, but it undeniably left its imprint on the genre.

“It’s not about making you jump,” Levin says. “Yet the whole movie is terrifying. It’s an existential fear that lives within us—the things unseen.”

Levin referenced Jaws heavily while writing the first Sharknado movie. And while his movie is nowhere near as subtle as Spielberg’s, he points to the decision to withhold the film’s titular weather phenomenon until the final act, which was inspired by the way Jaws keeps the full might of its great white shark a mystery for much of the movie.

“Spielberg’s ability to terrify you with what you don’t see also helped me a lot in both of my films,” Peyton concurs. “His use of pacing and music and building tension in Jaws really helped me, especially with San Andreas and Rampage.”

Byrne, who took a similar approach while directing Dangerous Animals, puts it bluntly: “Don’t overdo the sharks.”

Anyone who sets out to make a shark movie is probably either extremely reverential to Jaws, extremely self-confident in their own filmmaking skills, or just in it for the payday.

“Thanks to Jaws, shark movies are always seen as a good investment,” says Mullen, who first joined the Sharknado franchise as a casting director and later wrote the scripts for Sharknado 5 and the subsequent finale, The Last Sharknado: It's About Time.

“People love shark movies because of Jaws,” adds Ferrante, who directed all six Sharknado entries, “and filmmakers love Jaws, so they want the sharksploitation genre to stay alive by making even more shark movie babies.”

But back when the satirical series was first getting started, its original screenwriter wasn’t so sure. Levin initially rejected offers to pen a script called Shark Storm. “There was no point making another shark movie because Jaws had done it perfectly,” he says. However, when the studio came back and revealed the title was now Sharknado, Levin changed his mind. “That’s the most ridiculous thing I’ve ever heard,” he recalls saying at the time. “As long as I could play it that way, it sounded fun.”

Turteltaub had similar misgivings when he signed on to direct The Meg, in which Jason Statham faces off against an ancient, 75-foot-long megalodon shark.

“Whenever I start a movie, there’s a part of me that thinks I’m setting out to make the greatest movie of all time,” he says. “But when I signed on to make The Meg, the best I could hope for was to make the second-best shark movie of all time.” He was also painfully aware that his absurdist action epic would be measured against Spielberg’s carefully calibrated thriller. “I kept saying that comparing The Meg to Jaws was like comparing Woody Allen’s Sleeper to Star Wars because they both have robots in them.”

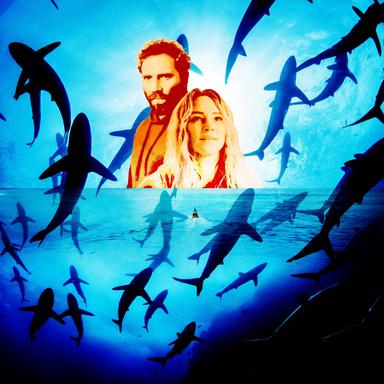

For Byrne, whose indie thriller Dangerous Animals subverts Jaws by giving audiences a human serial killer using innocent sharks to cover up his murders, the script by Nick Lepard felt like a revelation. Instead of simply swimming in Spielberg’s wake, Dangerous Animals held up a mirror to the classic movie and the ways its influence rippled across the past 50 years of cinema.

“I felt like he’d kind of cracked the code,” Byrne says of Lepard’s script. “It was the first original shark film since Jaws. Because the shark isn’t the monster. Man is the monster. We are the monster.”

While the original Jaws may be a perfect movie that holds up five decades later, the film’s many sequels aren’t quite so unassailable. Fittingly, when Mullen picked up screenwriting duties for Sharknado 5, he looked to another unserious sequel. Jaws: The Revenge, the fourth and final movie in the franchise (tagline: “This time, it’s personal”), features Michael Caine and some incredibly corny-looking special effects. For Mullen, it was the perfect inspiration.

“I love camp that doesn’t mean to be camp,” he says. “Jaws 4 takes itself so seriously, it’s amazing.”

Thunder Levin didn’t really appreciate Jaws until he was in film school, but once he started taking the movie seriously, he recognized it for what it really is.

“It’s actually a little character drama,” Levin says. “Calling it the first blockbuster is just a commercial reality, but it wasn’t structured like a blockbuster.”

Spielberg’s decision to film on location at Martha’s Vineyard and cast locals for most of the smaller roles, along with a focus on character development and depth, gives the world of Jaws a lived-in feeling that’s unlike most modern blockbusters. It’s a big part of why the movie still holds up, and a key lesson that almost everyone interviewed for this article brought up as influential on their own work.

“The real lesson from Jaws is: You better create characters people care about; otherwise, they’ll just root for the shark,” Mullen says. “In Jaws, it’s Chief Brody. You care about him and his family. That’s a huge part of what makes it work.”

“There’s an almost improvisational feel to everything at times,” Ferrante adds, “from the early family moments where you truly care about Sheriff Brody, his wife, and kids all the way to stuff on the boat in the last hour where it’s total anarchy at times as they’re held hostage by madman Quint [Robert Shaw].”

Byrne takes it one step further, arguing that the characters in Jaws are so interesting you don’t need the shark at all. Movie fans may disagree, but Byrne proposes an intriguing theory.

“For any horror film to work, you need to be able to take the horror out and the film still works,” he says. “It’s exactly like The Exorcist. You take the possession out, and it’s about a mother’s sense of helplessness. That’s great dramatic storytelling, and the horror is the icing on top. Otherwise, it’s just kills.”

Levin tried his best to instill the same type of character development and depth into Sharknado, even if it was sometimes an uphill battle. He brings up Jaws’ famous Indianapolis speech, a four-minute monologue delivered by Robert Shaw in the final act of the film that explains his character’s hatred for sharks. Levin’s original Sharknado script included a three-page “verbatim” adaptation of Quint’s speech with only a few names and details swapped out.

Ultimately, the studio made him cut down the monologue to something a bit more digestible for a made-for-television B movie. But Levin maintains it’s scenes like this that make Sharknado more than another sharksploitation cash grab. “If you focus on the characters and make them believable, people will care,” Levin says. “People will read this and say, ‘How do you explain Sharknado?’ But Sharknado could have been a lot more superficial than it was. I tried to put something in there that made it more than just sharks falling from the sky. I like to think that was at least part of what made it successful. I concentrated on making believable, genuine human characters as much as I could, given the assignment. That lesson from Jaws has always stuck with me.”