“I think we used up all the perfect.”

That Luthen line to Kleya sums up the feeling of watching Andor’s credits roll for the final time. After its transcendent, transformative run, Andor is done. And it concluded as it proceeded: with hardly a note or a quote out of place.

There was no trench run in the three-part finale, no battle between massed fleets, no lightsaber duel. No set piece more explosive than run-ins with a few agents and troopers at a hospital and a housing complex. There wasn’t even one last mother of a monologue: Like the last two episodes of Season 1, the ending of the second season and the series couldn’t help but be a bit overshadowed by the high points that preceded it. Yet the last of Season 2’s four mini-movies, directed by Alonso Ruizpalacios and written by Tom Bissell, was everything it could or should have been, considering the story constraints imposed by Rogue One: poignant, elegiac, devastating, inspiring, even somewhat surprising. I’m so sad that I’ve seen all the Andor, and also so fulfilled.

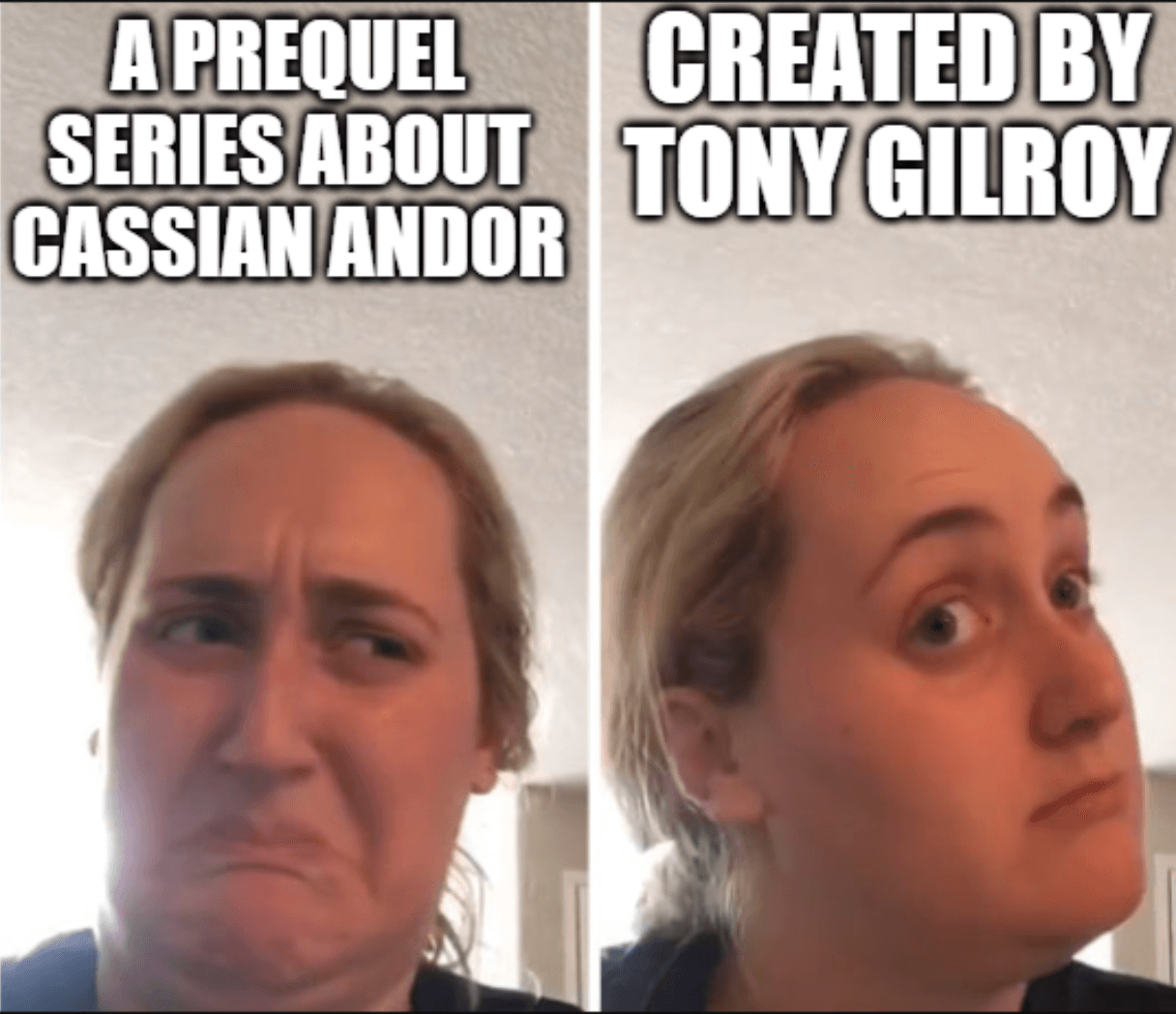

It's hard to remember now, in its moment of triumph, but much like the rebellion, Andor had humble origins, hype-wise. Forgive me for memeing, but this image more or less sums up my reaction when I first heard about the series:

Cassian Andor wasn’t exactly Glup Shitto, but the concept of a prequel to a prequel, and a spinoff of a spinoff, seemed symbolic of Disney’s recursive Star Wars storytelling strategy: The success of Rogue One would instantly be mined for more content tied to the original trilogy. I didn’t suspect that Andor would, one day, be as luminous as any other Star Wars project in the Lucasfilm firmament. However, Tony Gilroy’s involvement suggested that the series might be more than derivative franchise fodder, and once the first footage surfaced, I was sold—a testament to the difference visionary creators can make, even working within a franchise framework. It’s not as if a Breaking Bad prequel series centered on Saul Goodman sounded so great—and yet.

Just as Better Call Saul became more than a prelude to Breaking Bad, Andor doesn’t seem like well-executed setup for preestablished Star Wars narratives. In my mind, it’s no more a prequel than Episode IV is a sequel. It’s not backstory; it’s just story. I’ll never watch Episode IV again without wondering what Wilmon and Kleya and Vel think about the Battle of Yavin, or how Bix and her (and Cassian’s) kid are doing, or whether Mon Mothma mentally thanks Luthen when the second Death Star is destroyed and the Emperor is (at least temporarily) toppled. More than that, though, I don’t need to watch Episode IV to feel Andor’s impact. I know that the big battles and victories are still to come as Cassian sets off for Kefrene. But Andor’s fine-grained portrayal of the roots of the rebellion, which Cassian has cultivated as carefully as the plants he waters at his house on Yavin, is so absorbing, so convincing, that it seems like the hard part—the important part—is already done, even before the Force users arrive.

Andor isn’t only for Star Wars obsessives, but it gave fans like me something precious: the feeling of communally experiencing Star Wars as if for the first time. I was born after the original trilogy ended, and the first Star Wars movies I saw on big screens were the special editions. While I fell for those films just as hard as the generation before me (and the ones after me), I’ve always envied the fans who had the high of seeing a subtitle-less Star Wars in ’77, when it felt fresh and limitless. No wonder I’m still so attached to the Star Wars Expanded Universe, de-canonized or not: The characters in those books, comics, and video games felt like my Star Wars, the Star Wars that didn’t predate me but bloomed just as I discovered the series at the tail end of the on-screen lean years between the first two trilogies.

Andor undoubtedly exists in close conversation with the rest of the saga: Not only is it situated within the same universe and chronology, but it also seems so transgressive and revolutionary largely because of the contrast in tone between Andor and stereotypical Star Wars. Nonetheless, the series suggested that Star Wars could do more than strive to imitate its ancestors—that in some respects, it could be better today than it was a long time ago. Andor proved it was possible to redefine a franchise after almost 50 years—not only to recapture the spirit of classic Star Wars, as the best of Rebels or The Mandalorian did, but also to pioneer a new framework for the franchise. Nostalgia is nice, but as those plucky freedom fighters on Yavin know, it’s exhilarating to be present at the start of something.

That productive tension between convention and innovation extends to the finale, much of which revolves around Luthen and Kleya, the two core characters left on the board whose histories and futures remained unwritten before the episodes aired. Luthen, we learn, was once an Imperial sergeant who revolted against orders to attack and pacify a populace. Powerless to halt the violence inflicted by his fellow soldiers, he invented a mechanical problem and simply sat out the attack, intoning “Make it stop” in both Basic and his native tongue. No one answered his prayer to the air, so he had to answer it himself—with help from Kleya, a refugee who hid in his ship and whom Luthen adopted as a daughter and accomplice.

When I watched the earliest flashback for the first time, I thought that Kleya could be Kerri, Cassian’s long-lost sister, spirited away from what I took to be Kenari by Luthen just like Kassa/Cassian was by Maarva. It would be quite a coincidence for two orphans from Kenari to wind up at the bright center of both the universe and the rebellion—more support for the notion that fate and the Force are gently tugging at the strings. (As Cassian says, somewhat tragically, in Season 2, Episode 9, “The only special thing about me is luck.”) But it would also be beautiful if Cassian finally found his sister only after Maarva requested he stop looking, unwittingly completing a personal mission to find and save his sister by putting the greater good before his own interests. It would bring the series full circle, too, poetically linking the conclusion to the first scene of the series, in which Cassian’s search for Kerri kicked off the events that propelled him toward Scarif. As Kleya says, “It would be you, wouldn’t it?”

But that’s probably just decades of exposure to Star Wars speaking. One symptom of Star Wars brain is believing that everyone is related because Luke and Leia were and because Rey, like Luke, was descended from a Sith lord. Of course, even if Cassian and Kleya were siblings, their parents, as far as we know, would be nobody: Cassian and Kleya come from nothing, as The Last Jedi dared to suggest Rey did. One way or another, the duo is defined by their actions, not by their midi-chlorian counts or heroic or villainous lineages.

And if they aren’t related, which seems likely—the attack on Kleya’s unspecified planet appears to have taken place well after Cassian’s departure from Kenari, different child actors play Kerri and young Kleya, Kleya seems to speak Basic soon after the rescue, the attack seems to have taken place in a more urban, well-populated environment than Kenari, and Gilroy described the sister story line as “unresolved”—well, that’s appropriate, too. Like countless others—including Din Djarin and Jyn Erso—they’re refugees buffeted by forces beyond their control. The Separatists, the Republic that morphed into the Empire (gradually, and then all at once), even the rebellion: They’re far from equally culpable, but they are all capable of cruelty. The planets and perpetrators change, but the victims keep coming.

Those victims include Lonni and his family. The ISB plant tips off his handler about the Death Star’s construction, telling Luthen that he’s found “something huge.” (Moon-sized, even.) I wouldn’t want to be a whistleblower like Lonni because his reward for years of high-risk service is a swift execution. Between Lonni in Andor and Tivik in Rogue One, it’s clear that being Death Star Deep Throat for the rebels can be hazardous to one’s health. “We can’t let you go, Lonni,” Luthen said in Season 1. “We can’t spare you.” He meant that in more than one way.

In Luthen’s famous monologue, he talked about burning his decency and his life. In the finale’s first flashback, Luthen’s superior says, “Any burners you got, he wants that whole street out there on fire.” In a later flashback, Luthen burns a literal bridge (on Naboo), thereby burning his and Kleya’s bridge to blissfully oblivious civilian life. (OK, that one was a bit on the nose.) In the present, Lonni tells Luthen “I’m burned,” just before Luthen burns him with a blaster bolt. And when it’s time to cover the tracks of their operation, Luthen tells Kleya, “I’ll do the burn.”

Maybe the Burninator should have left that task to Kleya, because Luthen nearly bungles it so badly that he undoes his life’s work. One of the great joys of a series like Andor, in which characters proceed along parallel paths, is seeing some of those tracks intersect in the endgame, as Cassian’s and Mon Mothma’s did last week. Andor watchers were anticipating a showdown between Luthen and Dedra Meero for almost as long as Dedra was. It happened in Episode 10, and it didn’t disappoint. (Well, it disappointed Dedra.)

“Is everything real?” she asks Luthen when she shows up at his shop. “At the moment, only two pieces of questionable provenance in the gallery,” Luthen says, seemingly referring to himself and his pursuer. (Not only is Luthen not real, but he also isn’t even Rael; he was originally Lear.) They both know what Dedra is doing there, but they’re so steeped in secrecy that they can’t drop their facades before they finish their dance. Dedra likes to play with her prey, so they parry and riposte until she brings out her prop, with a flourish: the fateful Imperial starpath unit recovered from Ferrix that led Luthen to Cassian and eventually led Dedra to Luthen.

On the one hand, it seems preposterous that Luthen wouldn’t be better prepared to take his own life, considering he’s been forecasting his demise since the start of the series and knows that the ISB is onto him. Hasn’t he heard of cyanide pills (or the Star Wars equivalent)? Alliance operatives used them! I’ll grant that death by Nautolan bleeder (his first attempt to silence himself) would’ve been badass, but it wasn’t a sure thing, and that wasn’t the time to improvise. “He always used to say, know your way out before you go in,” Kleya tells Vel. Luthen knew he would go out fighting, but he should have paid more attention to the details of his self-imposed death sentence.

It seems similarly preposterous—or “terribly perplexing,” in Krennic’s words—that Dedra could “balance such passionate competency with the mindless decision to confront Luthen Rael on [her] own.” On a lesser show, we could complain about inconsistent characterization. This is Andor, though, a show in which every little detail, from Melshi’s blaster to Partagaz’s language about rebellion being a disease, seems to have been thought through thoroughly. Naturally, the groundwork was laid long ago for both Luthen and Dedra to biff their confrontation.

“Has it ever crossed your mind that Partagaz put me on Axis because I don’t seek glory?” Heert asked Dedra in Episode 4 of this season, drawing a distinction between himself and Dedra, his former boss. Luthen, last season, acknowledged “my anger, my ego, my unwillingness to yield.” Intellectually, Luthen may have accepted that “the ego that started this fight will never have a mirror or an audience,” but on some level, Luthen likes being the mysterious “Axis.” Alliance leadership may resent him and “run him down,” but Dedra, who’s chased him down, doesn’t underestimate him. She fantasizes about being the one to catch him.

“People fail,” Luthen said at the start of Season 2. “That’s our curse.” He and Dedra may be sharp, but neither is exempt from failure, which costs Luthen his life and Dedra her freedom. Predictably, Luthen’s self-reliance and insistence on seeing things through personally did him in: Dedra, despite not understanding what motivates Luthen, cracked the case because she read a report about a spy who confessed he’d been recruited by “a man with a Fondor Haulcraft full of antiquities.” As Cassian tells Kleya about Luthen, “No one can do this alone. He knew that. He just couldn’t swallow his pride.” “Make It Stop” illustrates that team mentality: It’s the only episode of Andor in which Cassian doesn’t appear, and while I missed Diego Luna, I didn’t want less Luthen or Kleya.

Like another fictional Lear, Luthen wasn’t an ideal dad. “Am I your daughter now?” Kleya asks him. “When it’s useful,” he responds. But his care for her belies his businesslike language. “Sold—but no smile,” Kleya says when she wins her flea market negotiation, as an approving Luthen flashes a fleeting smile for free. Later, he confides, “I’m only afraid of what I’m doing to you.” Kleya, who’s equivalent to “a team of three,” is always useful. But even though her mission of merciful assassination is an assignment Luthen has groomed her for from childhood, it’s still heart-wrenching for her to heed his words about “making a choice.” One of the things Luthen said he sacrificed in Season 1 was love. But Kleya’s tears as she sits by his side at the hospital contradict him. She loves Luthen, and as he lets out his last breath, he seems to have found the peace he said he’d given up all chance at.

“Had to be done,” Kleya later tells Vel about her mission to seal Luthen’s potentially loose lips. (Dr. Gorst is gone, but his torture mixtape might not be.) Mon’s cousin answers, “It gets tiring saying that, doesn’t it?” Kleya knows what she has to do, and she has the strength to do it.

Luthen’s last gift to the rebellion may seem extraneous, considering Cassian was about to receive the same tip about the Death Star from Tivik. Or was he? Without Luthen’s report priming the rebel brain trust for news about a superweapon, Cassian might not have hurried to Kafrene for that rendezvous, and he and Mon might not have been as inclined to trust Tivik. All too often, crucial warnings are ignored, and Luthen made it less likely that the rebels would overlook an existential, time-sensitive threat. But fittingly, he didn’t sound the alarm or act on the intel alone. Alliances aren’t solo acts.

As was foretold, the end of Andor led directly into Rogue One, complete with identical costumes and haircuts and the return of Admiral Raddus. Like many others, I’ll soon rewatch Rogue with the ending of Andor in mind. Maybe I’ll take in the original trilogy, too; the musical medley in the last episode’s credits made me hanker for John Williams. Andor foreshadowed (and should enrich) Rogue One in ways that aren’t as heavy-handed as Palpatine telling Anakin that he’ll watch his career with great interest or Obi-Wan joking about Anakin being the death of him.

Where the sequel trilogy undercut the originals by undoing their outcome—while admittedly making the point that happy endings aren’t permanent—Andor makes those classic characters’ efforts more meaningful because they’re completing a relay race begun by Andor’s street-level heroes. Remember the baton pass at the end of Rogue One, when Cassian, Jyn Erso, and Co. give their lives to transmit the Death Star plans and a series of doomed rebels play hot potato with the hard copy as Darth Vader hunts them down? Well, now we know the provenance (to borrow a word from Luthen) of all those handoffs. The chain that ends with A New Hope’s heroes shepherding the plans from Tatooine to Yavin began with Lonni, Luthen, and Kleya.

Gilroy and his writing team had ample time to plan, and little is left unaddressed. Vel and Cassian drink to the fallen, although Cassian concedes, “Can’t toast them all, can we?” (The list they reel off is about to get a lot longer—and will include Cassian himself.) Nemik’s manifesto has posthumously broken containment. The dead speak! (Sorry.) “Who do you think it is?” a haunted Partagaz of the manifesto asks just before he shoots himself, his voice full of fear and frustration. The entire rebellion is sharing its dreams with a ghost who’s beyond the Empire’s reach. As Luthen told Dedra, the rebellion is “everywhere now.” Nemik would insist it always was.

Meanwhile, B2EMO has made a new droid friend on Mina-Rau, and he’s probably co-parenting Cassian Jr. (or maybe baby Maarva)—the most uplifting character introduced in a closing Star Wars scene since Broom Boy. It might seem corny, if not for Adria Arjona’s multilayered expressions, the need for a little light in the darkness, and the way this unexpected sight reframes both Bix’s departure from Yavin and Cassian’s death. Are Bix and her baby greeting the first of the sunrises that Luthen knew he’d never see?

In addition to these check-ins on (or salutes to) the good guys, the denouement makes time for comeuppances for Perrin, whose drinking and dallying with Davo Sculdun’s wife don’t seem to be sparking the joy he talked about back at his daughter’s wedding; for Partagaz, who says, “Best of luck to us both” but soon divines that it’s bad luck Partagaz; for Dedra, who gets grilled in the same room where she once questioned Syril and is then sent to Narkina to indefinitely display her downturny mouth. “If you’re not a rebel spy, you’ve missed your calling,” says Krennic, caustically. Dedra may be busy learning what “on program” means, but in a different world, maybe she and Cassian would’ve been on the same side.

Other minor moments stayed with me: Krennic jabbing his finger down on Dedra’s skull. Luthen ordering Kleya to “do it”—another nod to the off-screen Emperor—before telling her to avert her eyes from the bridge on Naboo before his bomb detonates, lest she look like she knew the explosion was coming. Kleya appearing to pad over to the radio at the workshop when Lonni rings “the big bell,” which seems to indicate that she lives there—and that like Cassian, she rarely sleeps well. Flashback Luthen telling Kleya, “We’ll be whoever we have to. It won’t always be up to us,” a sentiment Bix echoes twice in Season 2, Episode 4.

Almost miraculously, the finale fits in some silly levity and dark comedy, too: the trusting grandmother at the hospital whom Nurse Kleya uses as cover; the ISB tech who’s a tad too admiring of Luthen and Kleya’s communications setup; K-2SO complaining about disobeying 18 orders and using Heert as a meat shield during his own Vader-esque slaughter in a hallway; Mon succeeding Luthen (à la Rebels) as the person saddled with the burden of butting heads with Saw Gerrera; the throwback Imperial sergeant on Coruscant who, like Sergeant Mosk on Ferrix, seems straight out of World War I—and who, like Mosk in the series’ first failed raid against Cassian, underestimates what he's up against. Both Preox-Morlana and the ISB should’ve sent more than a single shuttle to take Andor down.

Like Luthen and Kleya, we need to accept what we’re leaving behind. Say what you will about this Star Wars era, but dammit, Disney gave us Andor. Movies may carry the franchise forward, but there hasn’t been a Star Wars film for five and a half years, a good deal longer than the span from The Force Awakens to The Rise of Skywalker. That lull will stretch to six and a half years before The Mandalorian & Grogu debuts, or seven and a half before Starfighter (supposedly) becomes the first Star Wars movie since the sequels that wasn’t adapted from TV. That doesn’t reflect well on the brand, but would you trade Andor for another theatrical trilogy?

In 2023, I argued that Star Wars series couldn’t all be Andor—not just because of the creativity and budget required, but because Star Wars can and should be many things to many people. I still stand by that: The worst way to honor Andor’s originality would be by trying to model every subsequent Star Wars project after it. Rianza chips on the table, though: I am having a hard time getting hyped for Ahsoka Season 2, The Mandalorian & Grogu, or Maul - Shadow Lord. Gilroy has rightly credited Dave Filoni, Jon Favreau, and The Mandalorian for creating the conditions that made Andor possible, but it’s been a few years since Filoni felt like the Chosen One. His love for the lore and faith in franchise tradition were assets at times, but they can be weaknesses as well. (Favreau and Filoni may have friends everywhere, but not in a writers room.) If you’ll allow me one more meme:

I don’t really mean that; maybe I just need to recalibrate my enthusiasm. I have time to: The on-screen Star Wars release slate is clean for the rest of the year, save for the third volume of Visions. Maybe by 2026, enough time will have elapsed since Andor that the show’s fans will be ready to let another Star Wars series into their hearts.

“What a bitter ending,” Kleya says to Cassian, who responds, “Nothing’s ending.” Alas, Andor is, in one sense: Sadly, its seasonal episode counts were never more than 12. But maybe bittersweet is more the mot juste. Cassian never knows about his son, but at least he has one: He’s left a better galaxy not just for the friends he has everywhere, but also for the family he doesn’t know he has on Mina-Rau. (Which makes his sacrifice even sadder.) As for Andor, its legacy will also live on so: Though there won’t be new episodes, I intend to trot out Andor dialogues and monologues for the rest of my days—and to periodically revisit the series, gaining new insights each time.

When he reaches the right floor of the safe house in the penultimate episode, Andor tells Melshi, “It’s at the very end.” That’s where we are, too. In 2022, before Andor premiered, I noted that sci-fi and fantasy needn’t be graded on a curve—that scrutiny and high standards are signs of respect and that thinking isn’t incompatible with appreciating Star Wars. After 24 episodes of Andor, few would question that. “We’ll take the quick way,” Cassian tells K-2SO in the pair’s last scene, before ordering the droid to “get us out of here” (a line he repeats in Rogue One). Andor didn’t take the quick way; Instead, it took us on the scenic route. Like Cassian, it accomplished its mission, albeit at great (financial) cost. And now, even Andor must, like Cassian, obey Luthen’s plea: Make it stop.