Obama and the Millennials: Hope, Change, and Disillusionment

A generation later, youthful optimism has given way to sober realizations as millennials look back on the Obama years and their unique relationship with himAt the Fifth Avenue apartment of one of the nation’s most prominent commodity traders, David Hammond was making small talk with a magnetic Black senator from Illinois who was running for president. Hammond, a thoughtful 22-year-old who had fathered a child before dropping out of college, had managed to use his private school connections to earn a spot on the senator’s campaign. Only Hammond did not actually exist. He is the narrator of New Yorker staff writer Vinson Cunningham’s 2024 novel, Great Expectations.

Cunningham sets the scene. Hammond and “the Senator” are standing next to each other at a VIP reception when the Senator signals to Hammond that he is going to start chatting up their expectant guests. “Now watch me do the cardboard-cutout routine,” he says to his disciple.

Hammond observes from a safe distance as the Senator skillfully interacts with potential donors in the glitzy home overlooking Central Park. “In the end they did treat him like a sign, like something whose outward image was intrinsic to its identity,” Hammond recounts. “They knew as well as he did that his platform wouldn’t change as a result of their chatter.”

It’s a sobering but accurate observation: The Senator seemed to understand the source of his appeal even in those more obscure days, when he was considered a promising, but ultimately long shot, young candidate.

Despite the odds, the candidate felt potentially transformative to those increasingly flocking to his nascent campaign in a time of economic uncertainty, climate anxiety, and rising inequality. Hammond later refers to him as “the nation’s one hopeful thing.”

I should mention here that Hammond is actually Cunningham, who shares the same biography and gift for discernment. And so it is that “the Senator,” of course, is former president Barack Obama, whose campaign and White House Cunningham worked for in their fledgling months. Great Expectations, then, is more of a retelling than a dramatization.

In our conversation last week, Cunningham humbly offered that his actual role on the Obama campaign wasn’t all that interesting. But he did get to witness, up close, how the campaign responded to the world and vice versa. And those youthful observations and mature reflections helped to fill a book that has been described as a “coming-of-age story” that helps explain the Obama phenomenon a generation later.

“It was interesting for me to be that close to what seemed like the center of the world,” Cunningham told me. “He [was] in many ways so exemplary that he could cause a symbolic paradigm shift. I think that’s what Obama represented for me.”

Notice that Cunningham said “symbolic” and nothing about what Obama might tangibly do to change the nation, let alone the world. Cunningham just assumed there would be change, as part of the grand sweep of history that had brought him and millions of other American millennials to that very moment.

“This guy is going to not just achieve as a president and do good things for the country, which I did think he was going to do, but he’s going to change a paradigm that’s going to [lead] many others in his way,” Cunningham explained.

Months after that glitzy donor reception, by the time the Senator claims an almost anticlimactic electoral victory over a John McCain–like opponent near the end of the novel, Hammond is already disillusioned. “I couldn’t admire the candidate … now that I could interpret the symbols he offered in such profusion,” he says. “He was a moving statue, made to stand in a great square and eke out noise. He mattered and didn’t.”

Hammond presumably reached this point well before millions of others, as the enthusiasm for this unprecedented candidate and moment was met by the disappointment of increasingly ominous circumstances.

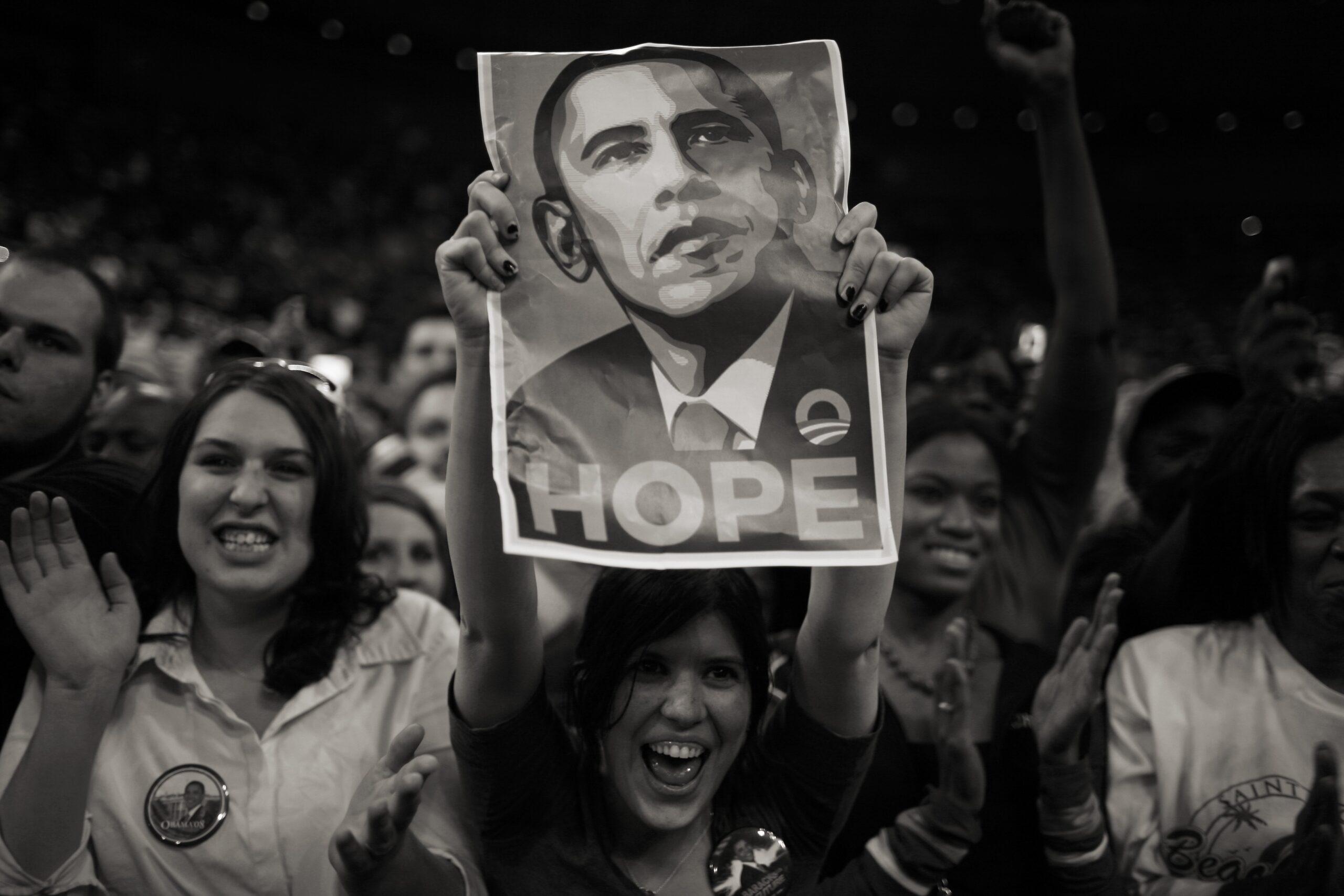

Obama—or was it the image of Obama?—engaged millennials in ways no previous presidential candidate had before, using social media and grassroots mobilization with the help of wide-eyed optimists like Cunningham. Two-thirds of voters under the age of 30 voted for Obama in the 2008 general election, leading to the largest disparity between young voters and other age groups in any election since exit polling began in 1972.

Those voters, more secular and more diverse racially and ethnically than older voters, turned to Obama hoping for an end to the war in Iraq; more government activism on health care, the climate, and the banking and loan industries amid the Great Recession; and a loosening of the grip of social conservatism on marriage rights, among other things. And despite their disappointment with the political stalemate in Washington and their waning support over the next few years, they again turned out in big numbers for Obama’s reelection in 2012.

“I still do have hope but without the very specific delusion that people in America could be exempt from the motion of history. I think that’s what that hope was. And I think you can have hope without that great, big delusion.”Vinson Cunningham

What did all the Hope and Change get them? A decade of obstinate opposition, starting with the Tea Party and culminating with President Donald Trump and the MAGA takeover of the government. Now the generation that once started out so hopeful is fated to become the first to not exceed their parents in terms of job status or income.

I asked Cunningham, now a two-time Pulitzer Prize finalist who also writes about television, film, and theater, what the generation—his generation, as I’m a Gen Xer—has learned from the developments of the past 20 years. Basically, now that millennials' preferred kind of change seems beyond their grasp and in the hands of Gen Z, what has become of his hope during this grim march toward American authoritarianism?

“I still do have hope but without the very specific delusion that people in America could be exempt from the motion of history,” Cunningham said. “I think that’s what that hope was. And I think you can have hope without that great, big delusion.”

The term “millennial” first entered the mainstream in 1991 in William Strauss and Neil Howe’s book Generations: The History of America’s Future, 1584 to 2069. The book was organized around Strauss and Howe’s theory that each generation belongs to one of four types—idealist, reactive, civic, and adaptive—and that these types repeat sequentially in a fixed pattern. Generations proposed that the pattern of American history includes spiritual awakenings and secular crises. As an example, the authors suggest that the “triggering event” that marked the coming of age for baby boomers was the assassination of John F. Kennedy.

For the so-called millennial generation, at that time a group of children no older than 11, Strauss and Howe predicted they would eventually confront a series of urgent social crises that would require them to “unite into a heroic and achieving cadre of rising adults.”

Almost a decade later, in their follow-up, Millennials Rising: The Next Great Generation, they prophesied that millennials—“more numerous, more affluent, better educated, and more ethnically diverse” than any generation before—were prepared for the challenges ahead. But that sunny outlook came with a warning: “If downbeat elders cannot harness this potential energy to a constructive mission of sufficient scope, even a minor economic or political setback could transform it into a dangerous juggernaut.”

As it happened, Millennials Rising was published just over a year before the September 11 terrorist attacks. This was followed by the Iraq War, Hurricane Katrina, and the Great Recession, which started with the collapse of the housing bubble in 2006 and homeowners defaulting on mortgage payments in large numbers the following year. Those were the circumstances that greeted Malcolm Harris when he started his freshman year at the University of Maryland in the fall of 2007.

“One of the reasons I went to Maryland is because I wanted to work in politics—I was a West Wing Democrat,” said Harris, who is originally from Palo Alto, California. “But I ended up friends with and working with a lot of left-wing radicals, even as I was a Democrat in high school, because that's who was out there opposing the war.”

In the weeks before the 2008 Iowa caucuses, Harris decided to spend his winter break knocking on doors around the state for former North Carolina Democratic senator John Edwards.

Harris felt drawn to Edwards’s progressive platform: He talked extensively about ending poverty, providing universal health care, and removing troops from Iraq, and his campaign was the first to describe itself as “carbon neutral,” a nod to his aggressive environmental efforts.

“I was walking through 2-foot-deep snow, knocking on doors, talking about John Edwards,” Harris said, “because as far as between [Hillary Clinton] and Obama and Edwards, he was the one who had the most left-wing policy program.”

But on the night of the caucuses, in Des Moines, Harris took a look around the room and found himself getting quietly envious at the coalition Obama seemed to be building.

“What I most remember is getting the distinct feeling that we had been on the wrong side generationally,” Harris said. “The Obama team was all the young people, racially diverse, gender diverse, even in Iowa. There were groups of excited young people, maybe voting for the first time, as I would be in that election.

“And then the John Edwards people were mad, old white guys talking about, ‘His middle name is Hussein.’ And I was like, ‘Oh no. I made a terrible mistake.’”

Obama won that caucus in January 2008, a seismic victory that proved he was a viable contender. In Great Expectations, Cunningham writes about that night in Iowa creating momentum for the primary victories to come: “The victory in Iowa had made its mark—was a mark in the national ground, had already become a kind of sculpture—and when the candidate touched ground in New Hampshire for his final visit, his lead, according to the polls, was ten points.”

Cunningham framed the win in even more grandiose terms during our conversation. “It was like, ‘Oh shit, this is the biggest thing that’s happening in the world anywhere,’” he said.

In solidly blue Connecticut, 17-year-old Krystie Lee Yandoli was motivated to get out and do some canvassing for Obama even though she couldn’t yet vote. “I was excited and idealistic and thought I knew everything,” she told me.

And Yandoli appreciated that Obama seemed to be the rare candidate who didn’t condescend to millennials.

“I always felt like he heard us and saw us and addressed issues and topics that were important to us,” she said.

By inauguration a year later, even people on the left who weren’t impressed by Obama’s political ambition had to admit they were excited about the possibilities.

“We were not immune to that generational moment,” Harris said. “It was D.C., and everyone was hype.”

He continued: “And then, like everyone else, I sort of experienced the deflation of the balloon over the next year, where the change that we expected to happen didn’t.”

Obama was 47 years old when he was elected president, making him one of the younger members of the baby boomer generation.

But millennials still felt a closeness to Obama, the tall, charming biracial man from Hawaii who turned down the lucrative opportunities afforded by his Harvard Law degree in favor of organizing in the Black neighborhoods on the South Side of Chicago. It helped that Obama told his own story first, writing the memoir Dreams From My Father before he even held political office.

His dad was a high-achieving immigrant from Kenya who was mostly absent during his childhood. His single mom, born in Kansas, balanced her own academic ambitions while raising him with help from her parents. He excelled at school but still partied a little too hard. He struggled to find his place in Chicago, greeted warily by Black community leaders when he arrived looking to organize residents.

It was easy to see his appeal: Obama faced his share of challenges but still remained eager to help people and make a difference in the world. Millennials, that cohort of people born to face down a series of global crises, now had someone who could prepare them for those perilous days ahead.

“His messaging was alluring,” Yandoli said. “It did not feel empty.”

Plus, Obama had a sort of calculated cool that played well with younger supporters. In Great Expectations, Hammond describes the Senator’s appearance at a reception at a famous music producer’s apartment in New York. “The televisual calm had crept back over the candidate’s face,” he says. “The speech the candidate gave was a toned-down, smartened-up version of what he said on the stump in the early states: his same bright hope but for an in crowd; graduate-level electoral inspiration.”

Among a crowd that boasted “two incredibly famous recording artists, he a rapper and she a singer”—a barely veiled description of Jay-Z and Beyoncé—the Senator came off as every bit the celebrity he was. At the time, this seemed like a good thing.

The critique shifted once Obama and his administration were in place, as is typical and inevitable for the incumbent leader.

Millennials grew anxious for the sweeping change promised during the campaign. But Obama’s political ambition suddenly seemed too mild for the moment, and organized Republican resistance made any gains temporary and tenuous.

The country’s recovery from the recession was slow and uneven, and student debt ballooned to $450 billion while he was in office, crippling millennials’ economic prospects as they hit the job market. Obama failed to secure a public option for his signature legislative achievement, the Affordable Care Act, which was seen as a betrayal by many young progressives. His administration also scaled back promises for environmental reform, even supporting expanded domestic oil and gas production.

Within a year, pollsters warned Obama’s historic advantage with millennials was already slipping away. Obama still won a large share of young voters in his 2012 reelection campaign, which was critical to his victory over Mitt Romney. But there were signs that the next generation of young voters would be more conservative, meaning their support would be more up for grabs without a political phenomenon like Obama atop the ticket in future elections.

“I was convinced to hope and then was waiting for the change, but the change didn’t come,” said Harris, who went on to author Kids These Days: The Making of Millennials. “And it seemed like [Obama] thought that the fact that Barack Obama was president was the change, and that if he could keep the rest of it stable, then that secures that change. And I think that was a poor analysis of the situation historically. That wasn’t what was really at stake in that moment.”

Yandoli, once so inspired by Obama’s candidacy that she knocked on doors for him before she could even vote, became disillusioned too. In 2013, she wrote a piece for Bustle headlined “I’m a Millennial, and I’m Disappointed in Obama.”

“With every day spent in the White House, the president’s bright-eyed idealism seemed to shift toward the same old politics of every man who came before him,” Yandoli wrote. “In turn, my idealism shifted right along with his. Am I disappointed? Of course.”

The Obama presidency obviously wasn’t all unsatisfying: His expansion of health care left the nation with its lowest rate of uninsured people in decades, he oversaw an increase in taxes on the rich unseen since the Reagan administration, and he helped to craft the groundbreaking Paris Agreement with more than 100 nations to limit global warming. His Justice Department worked diligently to reduce incarceration and police abuse; he used his executive power to create the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, which offered young immigrants temporary protection from deportation and allowed them to work; and his administration was inarguably the most aggressive in winning and expanding rights for LGBTQ people.

“I think people draw a very tight line between ‘We had Obama’ and then ‘We had Trump.’ And I just think Obama was present for many of the crosscurrents that would lead to Trump. The whole century has been going in this direction. From 9/11 to today is a whole cloth.”Cunningham

But those political and legislative victories were fragile, and many were made temporary after the election of Donald Trump in 2016. “Obama sought to be a transformative president and failed,” wrote Elaine Kamarck, a senior fellow in governance studies and the director of the Center for Effective Public Management at the Brookings Institution. “That’s because a presidential legacy is not simply what a person accomplishes in office but whether or not he leaves behind a political party strong enough to nurture and protect the legacy. From what we know about Obama’s post-presidency he intends to try and create a new generation of Democrats who will run for office. That is laudable but it may be too late.”

In the 1990s, Strauss and Howe expected those then-baby millennials “to become America’s next great generation.” Instead, they’ve been thwarted by economic and political instability for much of their adult lives, as “the nation’s one hopeful thing,” as described by Hammond in Great Expectations, showed them the practical limitations of hope. History, it seems, is unconcerned with unprecedented protagonists and storybook endings.

“I think people draw a very tight line between ‘We had Obama’ and then ‘We had Trump,’” Cunningham said. “And I just think Obama was present for many of the crosscurrents that would lead to Trump. The whole century has been going in this direction. From 9/11 to today is a whole cloth.

“This guy seemed, in many ways, so exemplary that he could cause a symbolic paradigm shift. But sometimes the Black guy’s just a guy.”

More than a decade ago, Harris started writing his book Kids These Days because he became exasperated with what he considered to be shallow analysis of millennials.

He recalled Strauss and Howe’s grand expectations for the generation and then the crude stereotypes and criticisms that followed as millennials failed to even meet the living standards of previous generations.

“I think ridicule was a powerful tool for explaining why this cohort was not rising into positions of power, positions of authority, positions of wealth,” Harris said. “And then society had to come up with reasons why this 25-year-old should be an intern instead of an assistant manager or something at every company in the world, in the country. And the reason was because millennials were childish or whatever.”

In Kids These Days, Harris connects how millennials have been ultimately stymied by tuition inflation, rising student debt, and stagnant wages. He makes the convincing argument that American society asks more of millennials than many of their forebearers, starting even in elementary school, where students are pressed into a tedious and increasingly laborious education system.

“I think ridicule was a powerful tool for explaining why this cohort was not rising into positions of power, positions of authority, positions of wealth. And then society had to come up with reasons why this 25-year-old should be an intern instead of an assistant manager or something at every company in the world, in the country. And the reason was because millennials were childish or whatever.”Malcolm Harris

The reward for all their good and diligent work has been a world hostile to their well-being and advancement, an unprecedented betrayal led by baby boomers. “Every authority from moms to presidents told millennials to accumulate as much human capital as we could, and we did, but the market hasn’t held up its end of the bargain,” Harris wrote.

By the end of the book, Harris calls on millennials to embrace drastic, perhaps even violent action to shift these historical tides.

“The situation, in terms of the welfare of the world, seems to be getting worse and worse,” Harris told me. “I think we need that dialectical understanding that we’re heading toward some sort of broad social conflict in which we're going to have to fight.”

To Harris, this is merely a call for another kind of hope and change. “We’re either going to be the first revolutionaries or the first fascists in America. Right now I look at someone like [White House Deputy Chief of Staff] Stephen Miller, and there's strong evidence for the fascist thesis, but I still believe that we will win, I really do,” said Harris, who touches on this in his latest book, What's Left: Three Paths Through the Planetary Crisis.

We probably shouldn’t expect to see Obama on those front lines.

While he’s been a reliable supporter of Democratic politicians since leaving office—often stumping for them during election season—he’s mostly shied away from using his considerable influence.

Like the millennials he once aggressively courted as a politician, he’s entered the content game with the production company he cofounded with his wife, Michelle Obama. His deft understanding of symbolism and image management has paid off handsomely now that he can fully pursue the life of a celebrity. Remember that quip about the cardboard-cutout routine from Great Expectations?

“Right now, as a figure, he's maddening to me,” Cunningham said. “I do think there is something symbolic about the motion from ‘I’m a community organizer’ to ‘I have a Netflix deal.’”

Said Harris: “One thing I’ve got to hand it to the conservatives on is that they were constantly saying he just wants to be a celebrity. And I thought that that was kind of a silly thing for a guy who had just pursued politics his whole adult life or whatever. But it’s hard to argue with that now.”

Near the end of Great Expectations, Hammond mourns the distance from his mentor, Beverly Whitlock. Whitlock is a pioneering Black businesswoman and longtime supporter of the Senator whose fundraising efforts come under federal scrutiny, forcing her out of the orbit of the campaign. As the Obama-like Senator closes in on an Election Day victory, Hammond can barely bring himself to celebrate. “I’d been deceived after all. In a way. I couldn’t muster indignation, as hard as I tried. Maybe I was the last to figure out that I had changed.”

That was a long time ago. The man who gave Hammond his voice has long since moved beyond his earlier awe at the phenomenon of the candidate, the man who is really Obama. He’s now an elder millennial, a writer, a father, and he’s since found other sources for hope. “I think sometimes disillusionment is just the name we give to growing up.”