Toward the end of his opening monologue at the 2025 Academy Awards, following a string of Late Night–style setups and punch lines and preceding a song-and-dance number, Conan O’Brien grew uncharacteristically serious. “Yes, we will honor many beautiful and talented A-list stars,” the longtime show host but first-time Oscars emcee said, “but the Oscars also shines a light on an incredible community of people you will never see: craftspeople, artisans, technicians, costumers. I can’t name them all; there are too many. Hardworking men and women behind the camera who have devoted their lives to making film.” Conan’s crowd work had singled out stars such as Demi Moore, John Lithgow, Adam Sandler, and Timothée Chalamet, but he promised to highlight some complete unknowns along with the lead of A Complete Unknown: “Many people we celebrate tonight are not famous. They’re not wealthy. But they are devoted to a craft that can, in moments, bring us all a little closer together.”

O’Brien was drawing a distinction between cast (the people who appear in movies) and crew (the people who contribute behind the scenes). Although plenty of actors are anonymous and numerous crew members—primarily “above-the-line” personnel like directors and writers—are well-known, in general, the former category is where the stars are. Perhaps relatedly, there’s also a sizable (and growing) divide between the two Hollywood demographics in another respect: racial diversity. Casts have long been more diverse than less public-facing crews—though casts are also far from representative of the population at large—but lately, the two groups’ proportions of people of color have further diverged.

Even with the “whitest man in America” (according to Conan) as host, the Oscars have diversified significantly in the past decade, a period during which the disproportionate whiteness of some years’ nominees made the Oscars a cultural flashpoint. The proportion of people of color among the nominees for this year’s acting categories was significantly lower than the nonwhite proportion of the U.S. population (roughly 43 percent), but notably higher than it was in the 2015 and 2016 ceremonies, when white actors captured all the nominations. That shutout for people of color inspired the #OscarsSoWhite campaign, which applied pressure that prompted the Academy to expand and diversify its ranks. The Academy also imposed new, albeit fairly lenient diversity criteria for Best Picture eligibility.

Those measures have paid dividends in diversity—in front of the camera. But behind the camera, the change has been much more modest, as evidenced by this year’s all-white nominees for Best Director and Best Original Screenplay. Many within the industry believe the issue extends beyond the Oscars. As NYU associate arts professor (and film editor and producer) Jason L. Pollard puts it, “It’s still not enough diversity behind the scenes.”

Multiple reports are published annually about diversity among actors, but there’s much less data about crews. Existing studies have been limited to snapshots that covered only a few years, or only a small portion of the tens of thousands of Hollywood crew members.

UCLA’s Entertainment and Media Research Initiative has tracked director and writer ethnicity back to 2011 and found a modest improvement in the prevalence of people of color, from 7.6 percent of writers and 12.2 percent of directors in 2011 to 12.5 percent and 20.2 percent, respectively, in 2024. USC’s Annenberg Inclusion Initiative has tracked the same jobs back to 2007, with similar results. Sinners, an original, critically revered genre film fronted by Michael B. Jordan (in multiple roles) and written and directed by Ryan Coogler, became the biggest movie in America last weekend, highlighting recent strides made by Black directors (which we’ll document below). But data on less prominent positions is more limited; USC has published some data on the racial background of composers and casting directors, and it issued one report in 2019 about a wider cross section of below-the-line roles from 2016 to 2018. But more comprehensive information, in terms of time span and personnel, has been lacking.

“We called one of our reports maybe five years ago ‘A Tale of Two Hollywoods,’ because you could see that the efforts to increase diversity that were being made were really just in front of the camera,” says Ana-Christina Ramón, director of UCLA’s EMRI, referring to the 2020 edition of its annual Hollywood Diversity Report. “There was a gradual increase in supporting casts with more people of color … but then behind the scenes it was stagnant.”

Ramón concludes, “It's clear that there is this systemic bias, and the only way to combat it is to face it head on.” Mapping out a problem’s persistence and scope sometimes makes it easier to tackle. So, in the absence of more complete preexisting data, we set out to explore the progress (or lack thereof) in this less visible, but no less important, part of moviemaking.

The Method

To do that, we assembled a historical dataset of hundreds of thousands of members of the movie industry, along with accompanying photos, which we downloaded from The Movie Database. We focused on movies produced (or coproduced) by American companies dating back to 1980, a subset that encompasses about 98,000 people and 150,000 photos—a much larger and more complete pool than previous efforts to measure diversity. Because our data included so many people, many of whom are much more obscure than the actors they work alongside, we couldn’t ascertain how each person identified their own race or ethnicity (which may not be 100 percent accurate either). Instead, along the lines of a similar process employed in a previous analysis of racial bias in baseball—as well as many additional studies by other authors, which have focused on racial biases in judicial sentencing, hiring, and health care—we built a machine learning model, trained on IMDb lists and academic research, to analyze names and photos to determine each person’s perceived race.

Kellee White, an associate professor at the University of Maryland School of Public Health, says that research based on “socially assigned or socially observed” race, which “mimics what happens in real life,” has formed an “emerging literature that talks about how [self-identified race] doesn’t really get at how we understand inequity.” Whitney Pirtle, a sociologist and associate professor at the University of California Merced who studies social inequality, says that research of this sort can be useful in the absence of universal self-reporting: “The reason why skin color can sometimes better approximate instances of racial discrimination is because it’s capturing how somebody is observing you, independent of how you identify, independent of other social factors that you have, independent of your class status or your legal status.” Pirtle adds: “All of those studies say the same thing, whether it’s the person behind the screen [doing the classifying] or some program: Folks are more likely to [be biased] to people who are darker skinned. … And so that has been replicated among people and among programming.”

It’s clear that there is this systemic bias, and the only way to combat it is to face it head on.Ana-Christina Ramón, director of UCLA’s Entertainment and Media Research Initiative

Algorithms aren’t definitive in any individual case, and they sometimes struggle to classify people of mixed ancestry (a challenge at times for humans too). But our model agrees with human perceptions of the race of other people about 95 percent of the time. “I do think that there’s probably a gray area here with assigning race to people. I think that’s a very personal kind of question,” says Nadia Abuelezam, a professor at Michigan State University who studies health inequities. However, just as some industry members have said, our data shows a striking lack of progress in racial diversity behind the camera since the 1980s—especially among higher-level decision-makers such as producers and supervisors. “There’s still a very important claim that you’re making about the need to improve equity in this field,” Abuelezam adds. “And I think that the value of that claim might in some ways outweigh the discomfort for some people, including me.”

A machine learning model isn’t the only way one can see that some communities are underrepresented among crew. “There are ways that humans process information that machines still don’t,” says Katherine Pieper, a professor at the University of Southern California who studies diversity in films. “And so I would say that to the extent that it's possible to get a sense of what the data shows from machine learning models, pairing that with human-guided information is probably the best way toward answering this question.” As we'll see, our method matches up well with demographic data gathered via non-automated methods, as well as the lived experiences of many people of color who have worked behind-the-camera jobs. Humans and computers are pointing to the same conclusion: While acting roles may have become more diverse in the last decade, crew jobs lag significantly behind.

The Findings

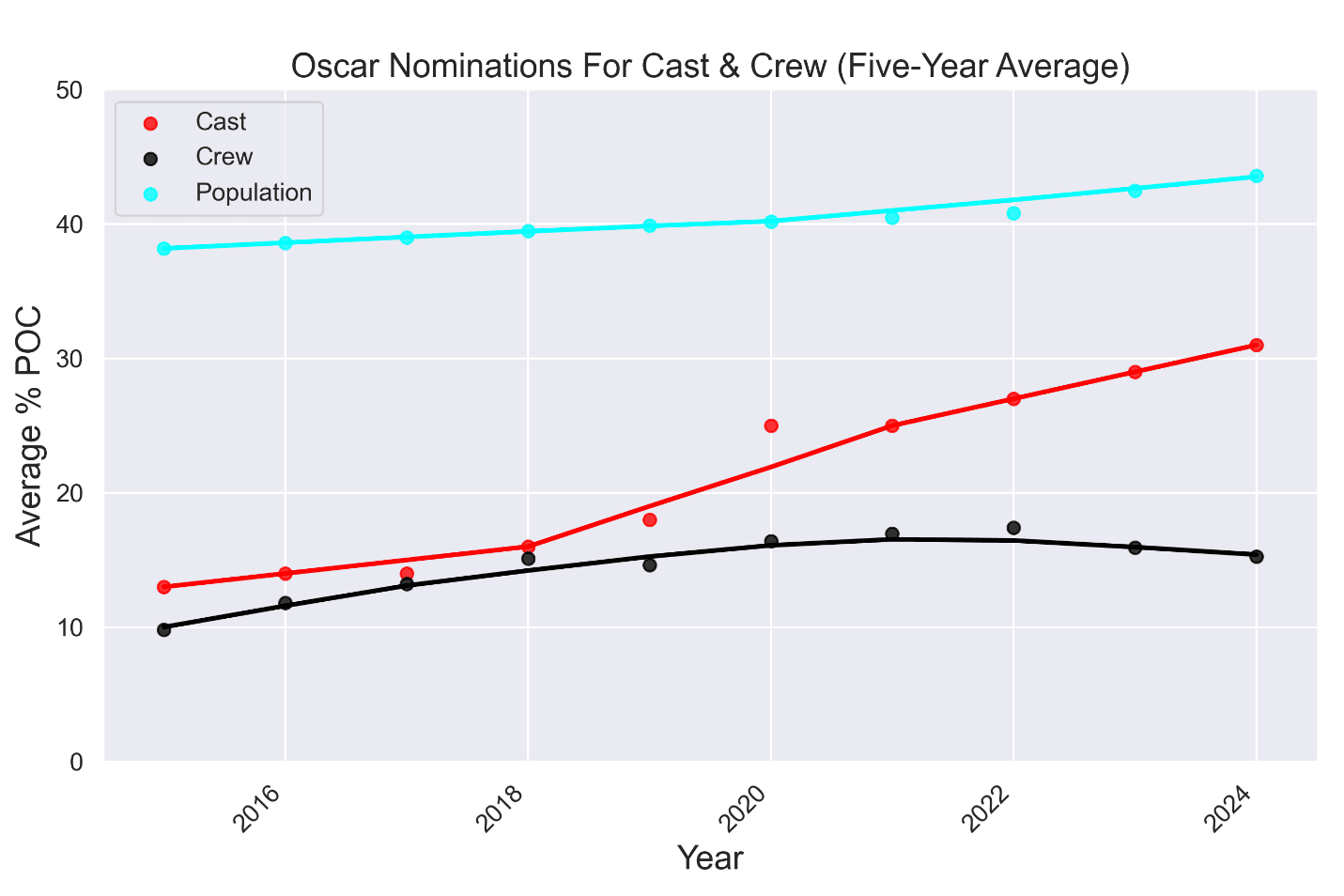

The graph below shows the change in the percentage of people of color among Oscar-nominated cast members and crew members over the past 10 years (dating back to the advent of #OscarsSoWhite), according to our data, compared to the proportion in the U.S. population. The rates were close a decade ago, but as nonwhite cast representation has more than doubled, increasing by upward of 15 percentage points and continuing to climb, nonwhite crew representation has increased by only about 5 percentage points, and plateaued or declined lately.

There are more than three times as many Oscar nominations for production roles as there are for acting roles. That doesn’t even count the music or writing categories, each of which contains about as many nominees as the acting categories. So when we refer to “crew,” we’re talking about the pool of people who compete for the majority of Academy Awards—and, more importantly, the vast majority of people who make movies. Actors are only the tip of the industry iceberg, and though there’s been a pronounced, if overdue, diversification of that very visible cohort—racially, at least, though less so gender-wise—that change may obscure a problem below the line.

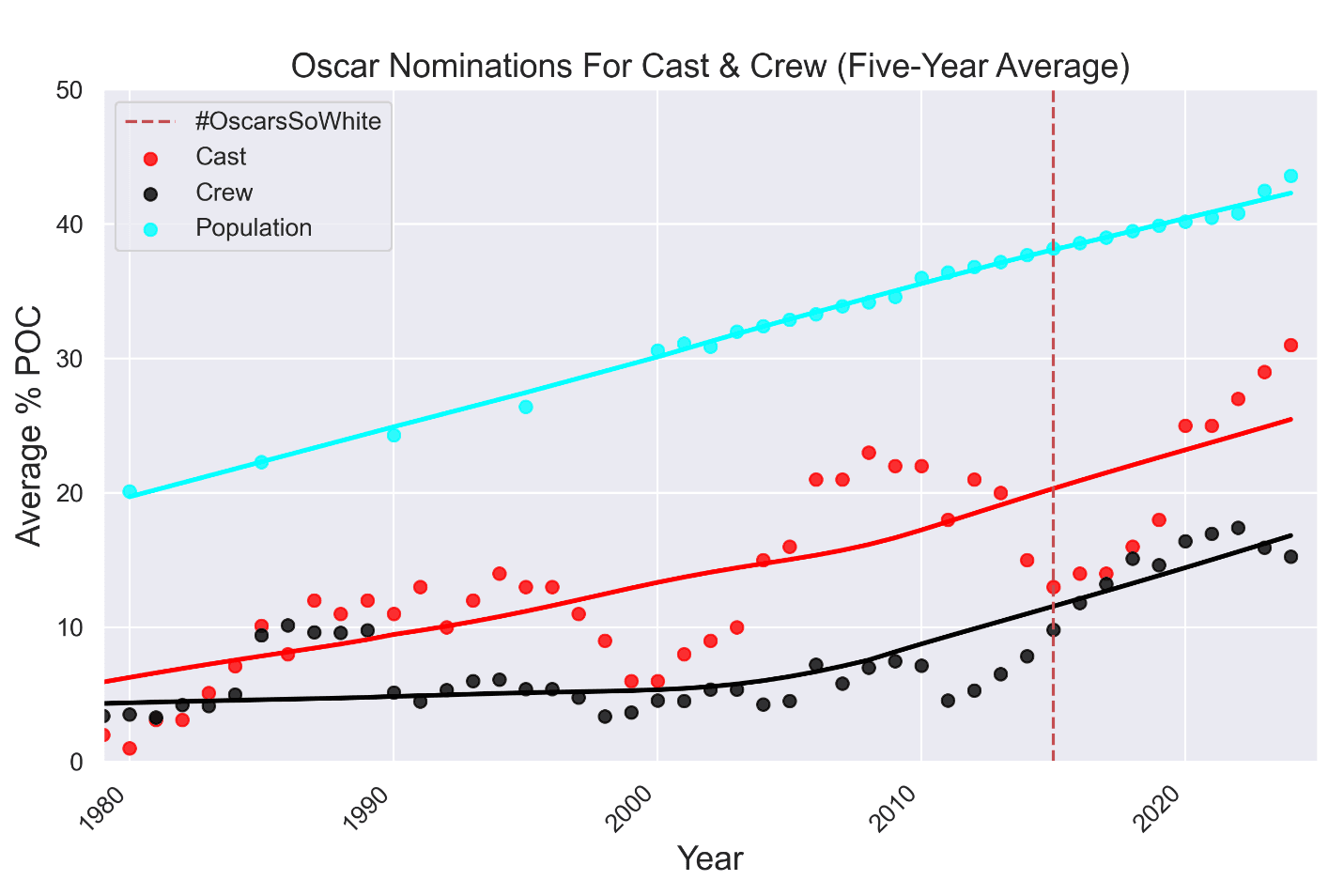

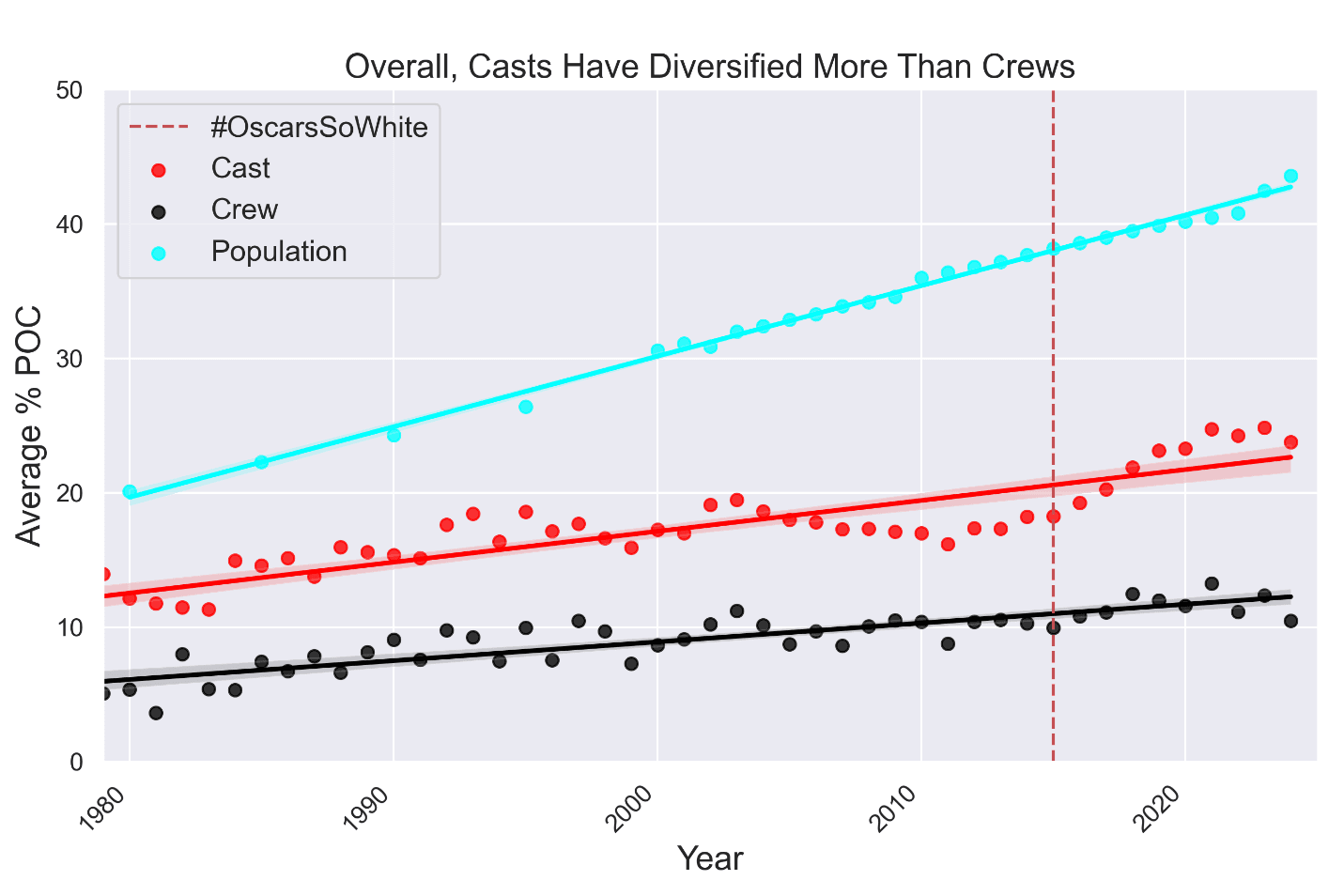

Oscar-nominated cast members and crew members were roughly equally white in the 1980s, but since the ’90s, casts have consistently featured higher proportions of people of color, aside from sporadic years when the rates roughly aligned.

Any given year’s Oscars categories comprise a fairly small sample of films, so the racial makeup of the nominees sometimes fluctuates significantly from one ceremony to the next. Using a five-year moving average, as we have on our graphs, helps smooth out the spikes and dips. But expanding our scope to all movies in our dataset reveals an even more stable, long-lasting record of cast diversity outpacing crew diversity.

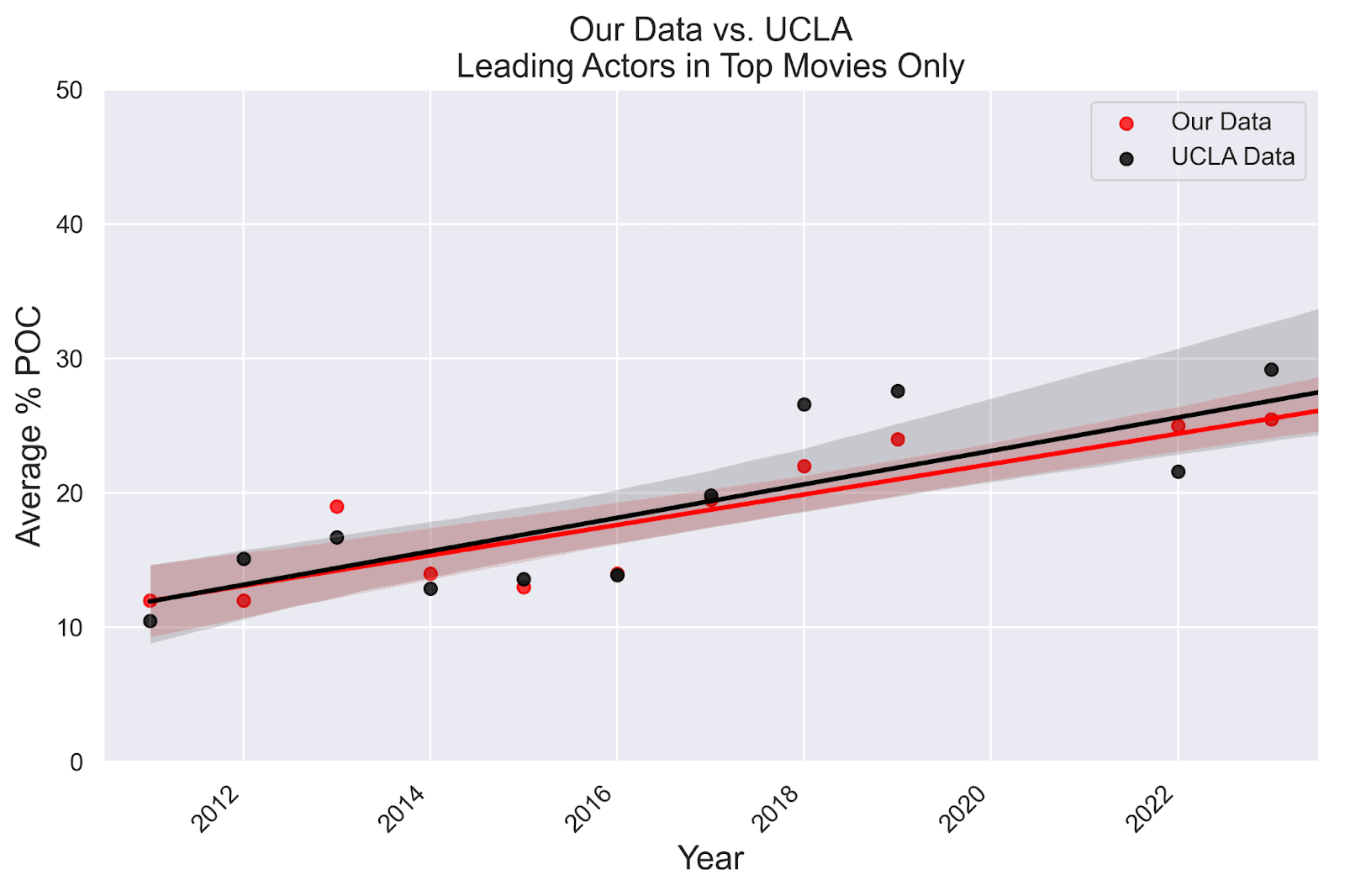

If we compare our data on actors of color to UCLA’s, which is gathered via different methodology, we find very close agreement. To produce their Hollywood Diversity Reports, which cover top-grossing films dating back to 2011 (excluding 2020-21), Ramón and her colleagues compile classifications from three subscription databases (none of which, she says, is unfailingly accurate), supplemented by info from actors’ interviews, promo materials, and more. Our results differ from theirs by less than 2 percentage points in a typical year.

Manually gathered data on the makeup of crews is comparatively scarce. But in their study of below-the-line crew in 2016-18, USC’s researchers found a severe lack of women and people of color in positions such as producer, casting director, composer, and editor. People of color held only about 5 to 15 percent of these jobs on top films, with little or no improvement over that span. “To hear that going back to the ’80s, the compilation of folks working behind the camera is relatively stable … it’s not entirely surprising,” says Pieper, one of the authors of the USC study.

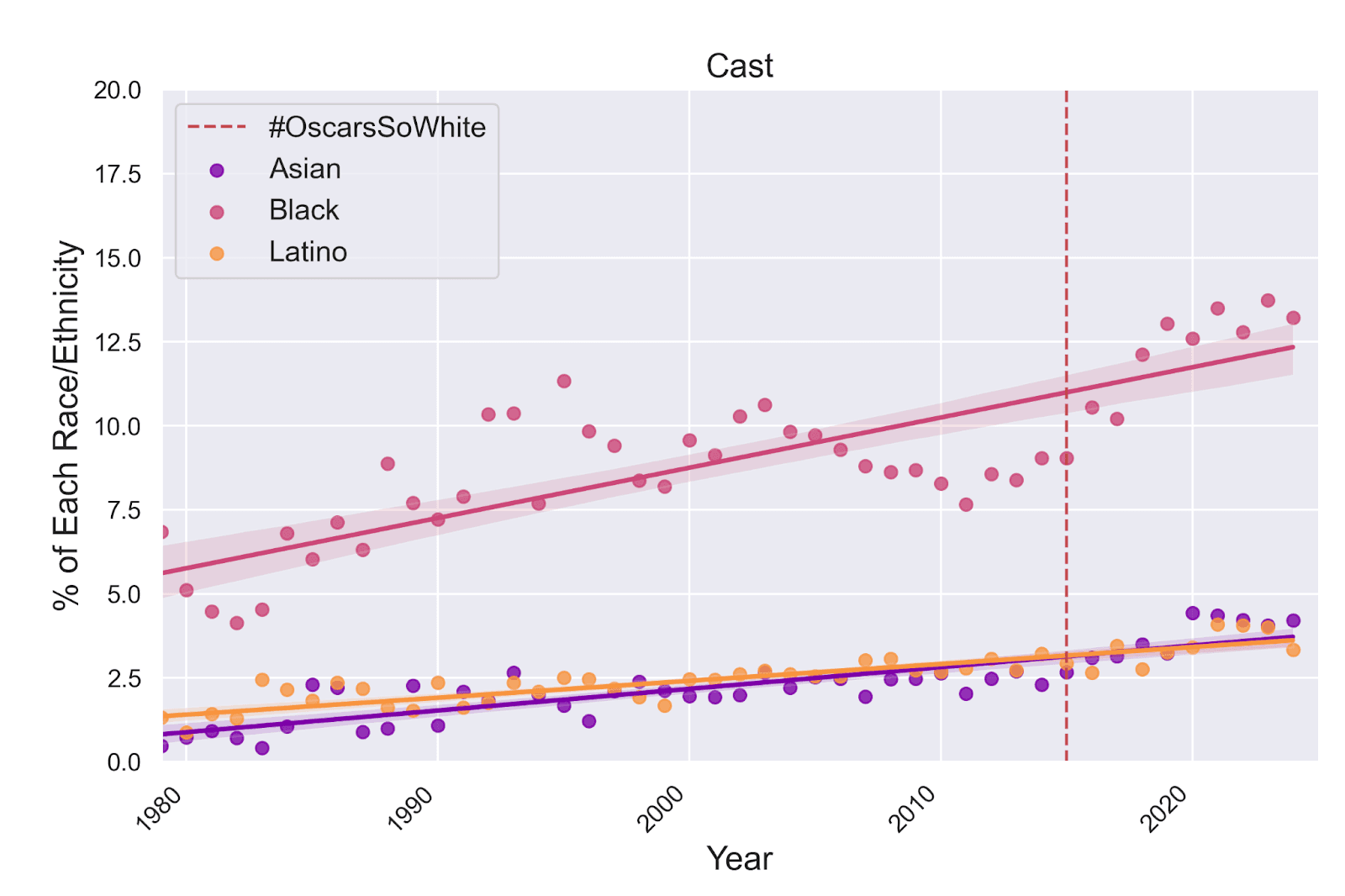

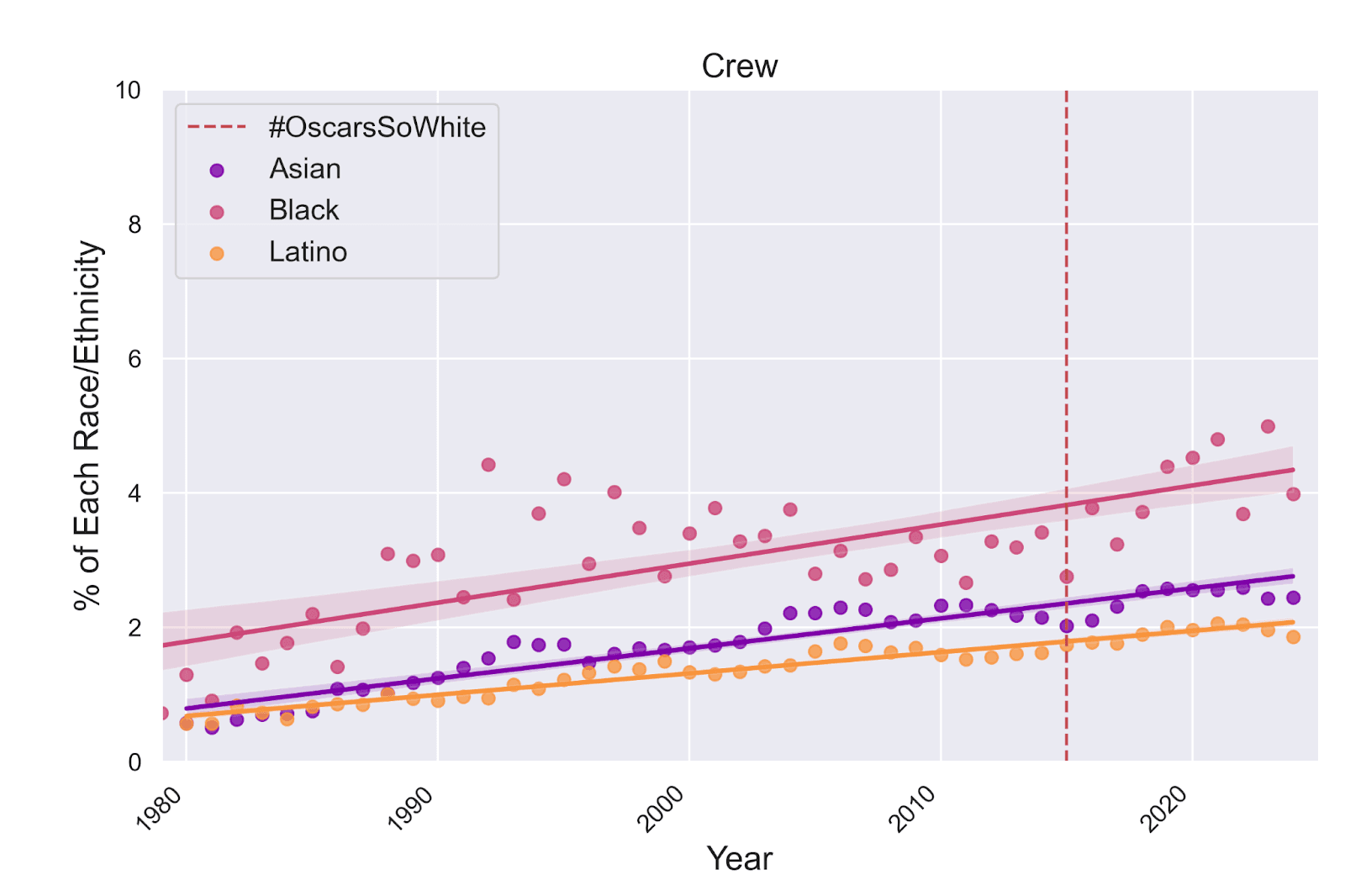

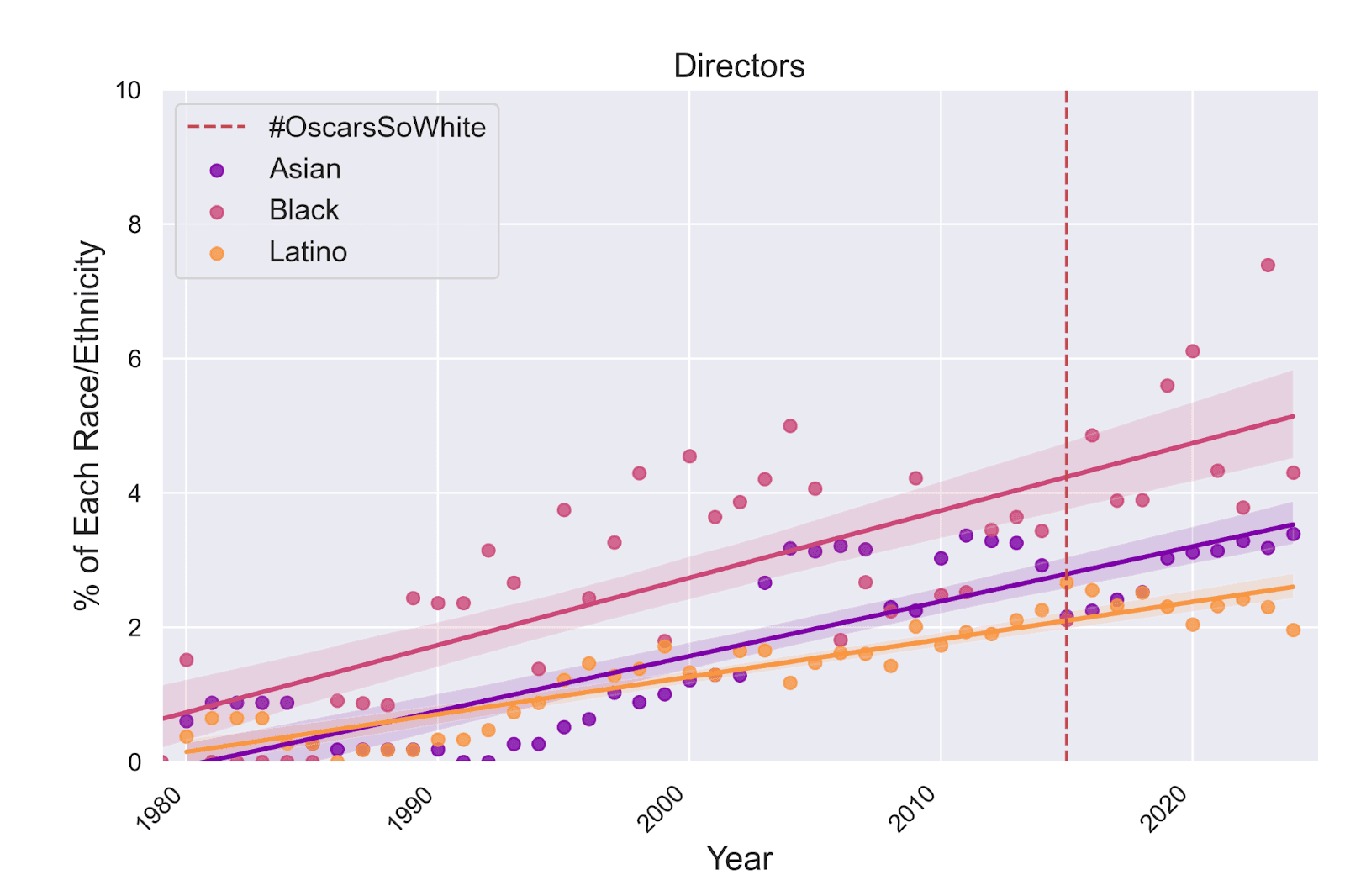

If we break down our data by ethnicity, the same trends for casts and crews stand out—and further evidence emerges of especially slow growth for Latino representation.

Some positions exhibit more equity than others, at least for members of certain ethnicities. For example, both UCLA’s data and our own show that Black directors, Coogler included, have helmed as much as 8 percent of all movies in recent years, which represents a significant increase compared to past decades and has drawn within the vicinity of the 13.7 percent of the U.S. population that identifies as Black.

But in the vast majority of crew roles, the presence of people of color lags far behind the demographics of the country. In the 1980s, roughly 5 percent of all qualifying crew positions were occupied by people of color. In the past 10 years, that rate has hovered around 12 percent. (Last year, it was 10 percent.) Over the same span, actors have gone from being about 10 percent people of color to about 25 percent. Oscar nominees have diversified faster than films as a whole; about 15 percent of the past five years’ Oscar nominations for crew members, and 31 percent of the past five years’ Oscar nominations for actors, have gone to people of color. But over the long haul, none of these upticks has kept pace with the diversification of the U.S. population.

“Have there been strides? Certainly,” says Axel Caballero, CEO of the Latino Film Institute. “Have things shifted over the last decade? Yes, perhaps. But there still seems to be a very systematic way in which production and the industry runs that tends to favor a particular way of doing things. And it’s been hard for our community to break through as a whole.”

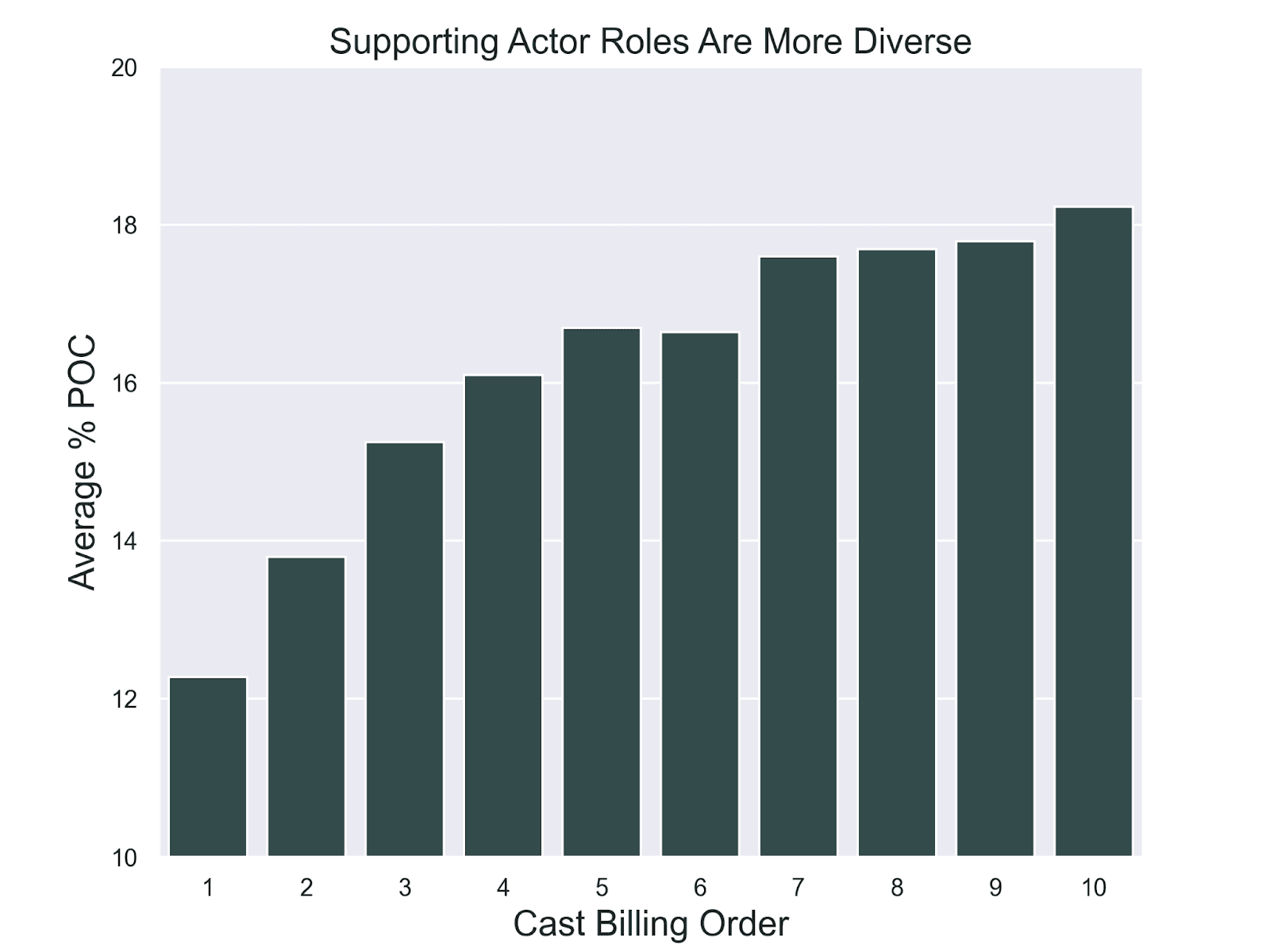

The Causes

According to Ramón, the disparate rates of representation among casts and crews reflect the studios’ typical response to outside scrutiny regarding race. “What usually happens is then the studios think, ‘OK, so they want to see more people like them,’” Ramón says. “So if we’re going to do that, then we’re going to get more people of color … cast on screen in order to appease them. And that’s where that tale of two Hollywoods happened, because that’s where it’s easy for executives to say, ‘Yeah, we can throw in more supporting actors of color.’ … That’s the minimal effort that they might make.”

These demographics matter not just in terms of how representation resonates with the audience, but also in terms of how stories get told—and whether they get told. “It’s a storytelling medium, and so you really want the perspective also to be from people behind the camera,” Ramón says. Caballero echoes that sentiment. “The more that you have different perspectives and people of different backgrounds work in all these technical components, the more that it trickles up into a production. There are many, many examples and cases where decisions that are made at the set level and in the preproduction of a film have gone all the way to the picture and have really graphically changed the film.”

Have there been strides? Certainly. ... But there still seems to be a very systematic way in which production and the industry runs that tends to favor a particular way of doing things.Axel Caballero, CEO of the Latino Film Institute

There are probably many more cases where a movie might have benefited from voices that weren’t in the rooms where such decisions were made. Emilia Pérez, which led the Oscars field with 13 nominations, also seemingly led in backlash from the communities the movie depicted, perhaps in part because of where its creators came from—or didn’t come from. The film featured a diverse cast—albeit one that was minority Mexican—but its writers, producers, and director were French and not really working from personal experience, which may help explain the elements of the movie that some critics called misrepresentations and stereotypes.

Director, writer, and editor Raafi Rivero cites the way director Ava DuVernay and cinematographer Bradford Young lit the Birmingham jail scene in 2014’s Selma as an example of diversity making a difference.

“It’s this brown skin on this black background,” Rivero recalls. “And brown and black are two different colors. But to a traditional Hollywood look, it’s too dark. I was sitting between my mom and my girlfriend at the time. And I was like, I’ve never once in my life sat in a movie theater and seen brown-on-black as the color palette. I got goose bumps. … It was just thrilling, the image, and I know it was because of all those people who were behind the camera that were able to produce this image and this color that everyone else would have said was wrong. Any other film, any other time someone would try to make an image like that, it would have been the first thing that got scrubbed out.”

Of course, some films might not even be conceived, let alone green-lit and adeptly produced, if filmmakers’ backgrounds remain mostly homogeneous. “When you ignore audiences, when you only play to one audience … you’re leaving out so much,” Jason L. Pollard, the NYU professor and film editor and producer, says, adding, “Behind the screen is not diverse, and so on the screen is not going to be diverse. How do you expect different stories to be told by just one group of people? That’s not realistic to me.”

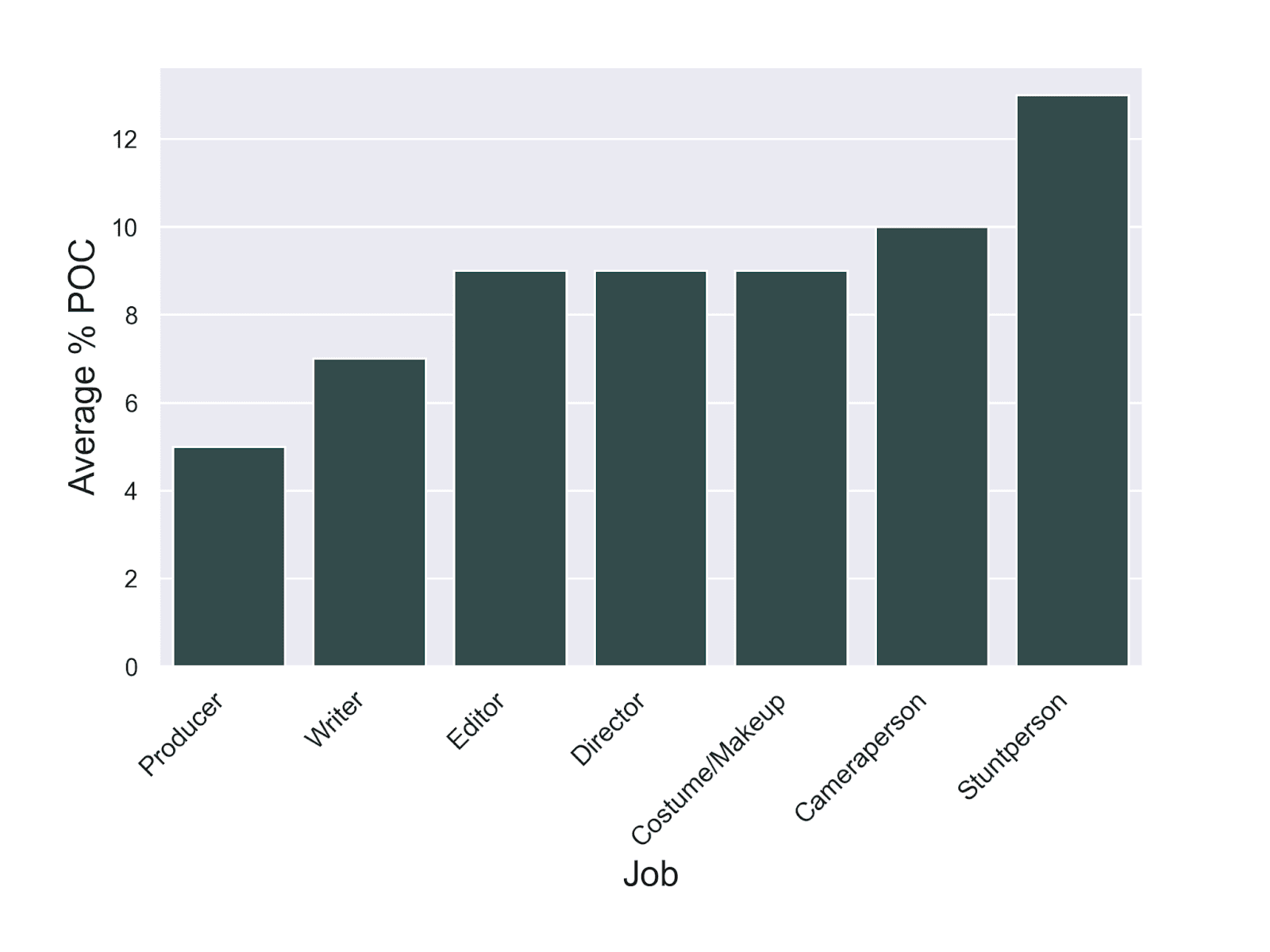

The following graph shows how the presence of people of color has historically varied among some of the jobs that qualify as “crew”:

Even within this category, we see some demonstrable disparities, which generally skew in the direction of greater seniority and responsibility for white crew members. Our research indicates that crew members of color are less likely than white crew members to hold “executive,” “supervisor,” “supervising,” or “coordinator” titles. In the full dataset, people of color made up about 10 percent of all non-supervisory positions, but only 6 percent of supervisory positions. Maryann Erigha, author of The Hollywood Jim Crow: The Racial Politics of the Movie Industry and assistant professor of sociology and African American studies at the University of Georgia, says, “The more prestigious roles and positions of authority tend to be occupied by white creatives, which leads to an imbalance of control and perspective.”

Producing is one of the least diverse subsets: Even now, about 95 percent of producers are white, down only slightly from roughly 97 percent in the early ’80s. “That’s definitely something that I think is clear and felt in terms of who has the power at the producer level,” Ramón says, adding that to reach a producer perch, “you need to go up in rank as a writer. And so it becomes very difficult for writers of color to break through to that upper level. There’s a lot of writers that have been working for years, and they’re good writers, but they don’t get a chance to … get to that producer level.”

Partly, Pollard says, the problem is “a pipeline issue,” though he acknowledges that “there could be some cases of racial bias.” That bias need not be bigotry to have a discriminatory effect; simple social dynamics could account for exclusion, because as Rivero says, “Film is very much a ‘who you know’ business.” As DuVernay, who started Array Crew, a database designed to connect below-the-line professionals from underrepresented backgrounds with movie producers and studios, said in 2021, “When hiring managers and studios and streamers said, ‘Yeah, well, the crew all looks one way because, you know, I can’t find anyone,’ the question will be, was that genuine?”

At the upper echelons, moviemaking isn’t just a “who you know” business; it’s also a “Do you have dough?” business. “One of the dirty secrets of the film industry is that it's a money game,” Rivero says. “At its worst, you could describe it as a playground for the rich. … More of those people who have means tend to be white, just based on the way our society is structured.” By contrast, he continues, “You see all the … production assistant roles, which is like the lowest job that anybody can get off the street, it’s always like two-thirds of the PAs are Black and Latino people. But when you get up to the next level, the coordinator level, most of the coordinators are white. And by the time you get up to [assistant director] and producers—the producer is almost always white.”

Stunt work is one of the more diverse subcategories on crews, relatively speaking. Nonwhite workers have made up about 10 percent of all crew positions, but 12 percent of stunt positions, according to our model. Despite that, they’re still unlikely to become stunt coordinators; only 8 percent of stunt coordinators in the sample have been nonwhite. Erigha says, “Stunts are risky, sometimes posing hazardous or health concerns. Sociologists have noted that racial minorities often perform the ‘dirty work’ in American society, work that is deemed undesirable and often goes unrecognized. Stunt work might fall into this category.”

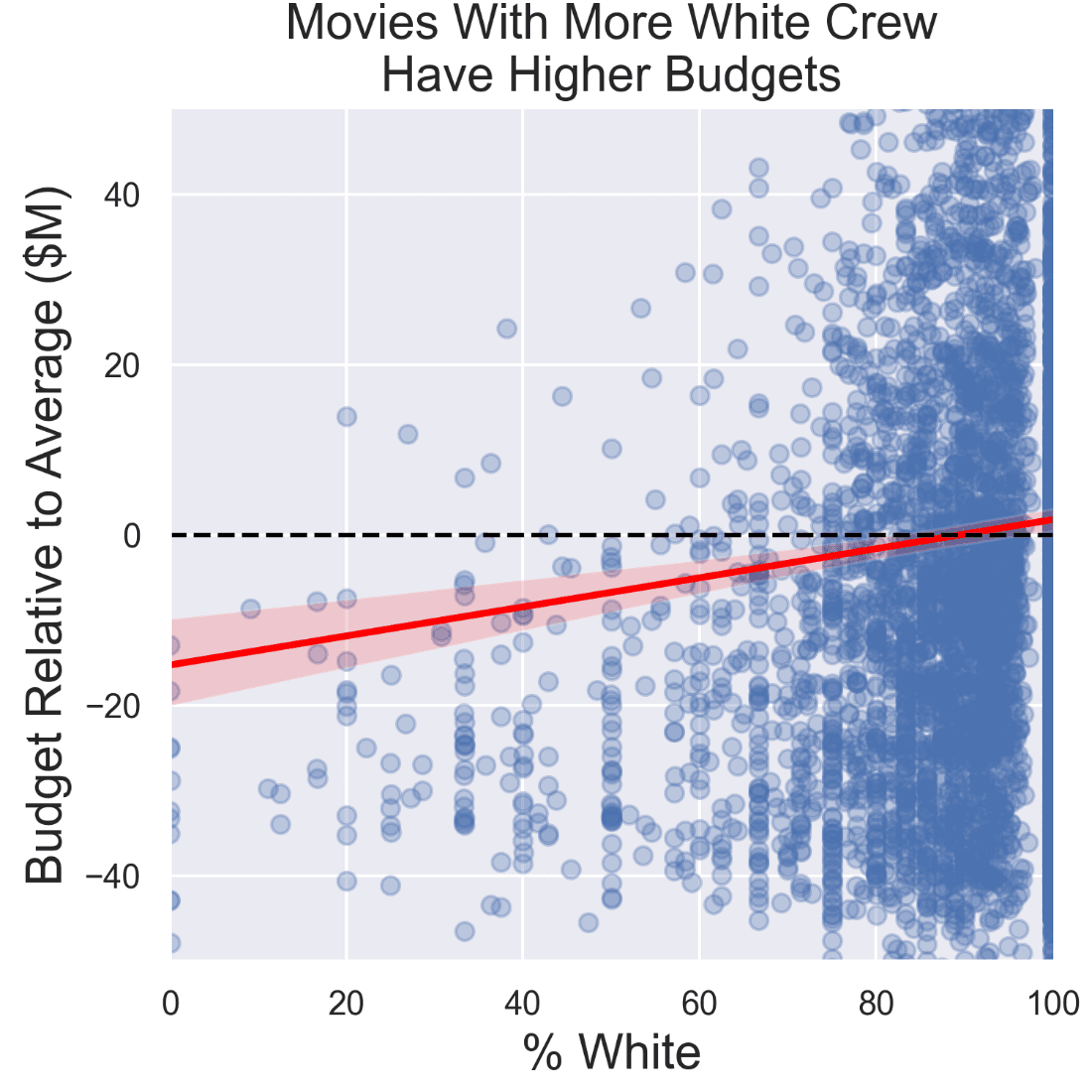

One upshot of all of this is that films with whiter crews have historically received greater resources, priming them to reach wider audiences and earn more revenue. Over the past decade, Ramón notes, many production companies “have seen the value of having more diverse crews. But oftentimes those are independent films or smaller films.” Thus, Erigha says, “when racial diversity is present in the film industry, it is deliberately concentrated in areas that are less funded.”

Coogler has coaxed blockbuster spends out of studios, both for the Black Panther films and now, to a lesser extent, Sinners, which still had a hefty $90 million production budget. On the whole, however, the budgets for movies with white directors, cinematographers, editors, casting directors, and producers have tended to be 10 to 25 percent bigger than those with nonwhite people in those positions; for every additional crew member of color, budgets have tended to be $210,000 lower. Directors of color, Erigha says, have been “underrepresented at major studios and less hired for the more technically inclined blockbuster franchise films.” Yet adjusted for budgets, movies with nonwhite directors make as much or more revenue than movies with white directors.

Even Oscar-nominated nonwhite directors work less and receive smaller budgets than their Oscar-nominated white counterparts. In the five years following an Oscar nomination, white directors make almost twice as many movies as nonwhite directors, on average. (That pattern holds for other Oscar categories, such as Best Picture, and other crew positions, such as cinematographer.) Nonwhite directors’ first films following an Oscar nomination have average budgets that are 44 percent lower than those of Oscar-nominated white directors, but those movies make only 14 percent less at the box office.

The lack of representation might be a blocked pipeline, but the lack of funding, that’s pure bias. People don’t believe that films with a cast featuring people of color will make as much money.Jason L. Pollard, NYU associate arts professor

“The lack of representation might be a blocked pipeline, but the lack of funding, that’s pure bias,” Pollard says, adding, “People don’t believe that films with a cast featuring people of color will make as much money.” Erigha says, “There is an assumption that films with racial minority casts do not play well overseas. These films tend to get smaller budgets, and directors of color are more likely to direct these films. But in the long run it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy, since films that are distributed internationally have an advantage to be commercially successful.”

According to Pollard, “People say things like, ‘We already have this type of film in the catalog,’ or ‘We’re already covering this issue,’ and it’s not true.” Instead, he says, lack of funding is “just discrimination.”

Ramón notes that per the EMRI’s research on writers, directors, and actors, 2024 brought “a little bit of a rollback” in racial diversity. Despite the success of some films fronted by nonwhite actors, including Wicked and A Quiet Place: Day One, Ramón reports that there were more films with all-white casts in the top 200 at the global box office than in any year since 2017. “Overall, the domestic box office performance went down,” she says. “To me that shows that … going backward is not going to be helpful for your profits.”

Time and further research will reveal whether 2024’s figures were a blip, the after-effects of the writers’ strike, or a symptom of a so-called “unwokening” manifesting itself in Hollywood as well as in the Trump administration’s attacks on diversity, equity, and inclusion. They’ll also answer the question of whether the industry’s lower-profile positions will ever mirror the makeup of casts. “Rolling back or maintaining the status quo with those behind-the-camera jobs is not a sustainable approach for an industry that’s already struggling,” Ramón concludes.

Crew unions IATSE and the ICG declined to comment on the findings in this story; the DGA and WGA didn’t respond to requests for comment. Crew unions typically don’t produce public reports about the racial makeup of their members, partly because they legally can’t compel people to disclose that information. The 2021 IATSE basic agreement included a DEI section that featured a “statement of commitment” to “increase employment opportunities for individuals from ‘underrepresented populations,’” as well as pledges to encourage the voluntary reporting of self-identification data and form a subcommittee to develop and oversee training programs, support internship programs, and expand outreach efforts. One obstacle to greater diversification is that some subsets of film crews tend to work in clusters of longtime associates that move from project to project, which tends to preserve the insular status quo.

“One thing I’ll say in favor of everybody in the film industry is that they all love movies,” Rivero says. “We’re playing dress-up for a living. The thing that animates every single person in this is that we want our version of playing dress-up to be something that everybody else watches and likes.” Or, as Conan said, something that can “bring us all a little closer together”—which would probably be easier if the system weren’t set up to keep some people apart.