Predicting the Breakout Heroes of the 2024 NCAA Men’s Tournament

Nine potential Davids who could slay Goliath and solidify their place as March Madness legends

I remember exactly where I was on March 20, 2010, when Ali Farokhmanesh chiseled his name into basketball history. I was in the bar of a Mexican restaurant in eastern Kentucky (this is where all special moments happen) when he hit this dagger to put Northern Iowa past Kansas and through to the Sweet 16. I couldn’t contain myself: I let out a huge, joyful Paulie Walnuts–style “HOOOOO” when it went in. The stones to take this shot, much less cash it in such a huge moment. I still remember its high-arching trajectory before it splashed through the net like a lobster tail plunging into a cup of butter in a Red Lobster commercial.

But that’s March, man. Don’t fool around in this territory. Fortune favors the bold. Scared money don’t make money. That might mean you come out swinging and whiff so hard you fall on your face—stay with me—OR, it might mean someone on your team has the shotmaking experience of their life and the building starts rocking, and the higher seed gets that “today is my day to die” look in their eyes.

Now, if you’re watching that as a Kansas fan, you understandably want to die. I can relate. Twelve years later, I found myself letting out a huge “NOOOOO” as some audacious 3s went down against my Cats. Remember this son of a bitch? Do you know who he’s pointing at in this picture? He’s pointing at me, conjuring haunting memories of that two-week period in March 2022 when Doug Edert led 15-seed Saint Peters on an improbable underdog run to the Elite Eight. If you took a sharpened blade for each one of Edert’s 117,000 Instagram followers and placed those blades pointing upward at the bottom of a pit, on March 17, 2022, I would’ve swan-dived in.

The storied history of March Madness has shown us that there are many paths toward becoming a hero (or villain, depending on your perspective), and Edert and Farokhmanesh are merely two examples. As unpredictable as tournament hoops can be, two particular species of player have a tendency to become main characters in March: craft bigs and dribble shooters. (You might also call the latter “bounce creators” if you’re at a watch party and you want other people’s eyes to glaze over as they cringe and plot your comeuppance.) In the chaos of the NCAA tournament, the home of quick turnarounds and unfamiliar opponents, these types are frequently put in a position to thrive. You gotta know who they are. Ask Kofi Cockburn about Cameron Krutwig.

Every year, we’re blessed with the opportunity to watch someone who is dying to introduce themselves to the world. I’m going to rattle off some names that I think could make that introduction this year and explain why I think it could happen.

Reyne Smith and Ante Brzovic, College of Charleston

This first entry is actually a duo, but they’re fun because we get our two archetypes on the same team; the added bonus is that both players are international and also left-handed! College of Charleston finished 27-7 overall and 15-3 in Coastal Athletic Association play, and that was in large part due to Smith and Brzovic. Smith, a 6-foot-2 junior from Australia, and Brzovic, a 6-foot-10 junior from Croatia, possess the type of chemistry that can really put points on the board. Brzovic is more of the Domantas Sabonis variety: not someone who will light it up from 3 or protect the rim at a high level, but he’s very much the hub of the Charleston offense and sets the table for its handful of shooters. His 20.9 assist percentage is in the 98th percentile nationally, according to CBB Analytics.

Reyne leverages his shooting with and without the ball. There are beautiful sequences when Charleston moves like one organism and his gravity allows a teammate to sneak into a wide-open look. When on the prowl for his own offense, the speed of Reyne’s release and the mobility of his entire shot process can catch a defense’s attention in a hurry. It’s an efficient motion without much dip, and he catches high and shoots high when the pass is right. He can be a bit wild with his shot selection in transition—he does not mind firing, even if he has minimal to zero space—but if he has a second to gather, his shots tend to find the bottom of the net.

There are few things in basketball as satisfying as a cohesive handoff tandem, and Brzovic and Smith are certainly that. Watch them with your dad, because Alabama—Charleston’s first-round opponent—gives up a ton of points and seemed a bit mentally fatigued when I saw the team in person at the SEC tournament. Charleston is a team with other weapons beyond these two, but the point is that they force teams to defend and communicate away from the ball, and that can be a recipe for upsets.

Tucker DeVries, Drake

As a player who’s been on the NBA radar for the past couple of years, DeVries is more of a known commodity, I grant you. I’m throwing a bone to the folks who see things through the NBA lens. But DeVries belongs in this group because he follows a template that we’ve seen lead to upsets in tourneys past: An NBA talent on a mid-major team quietly does their business throughout their career and garners respect from a chunk of the basketball community but still hasn’t punched through and caught the attention of the mainstream basketball world until a March Madness run. Both CJ McCollum and Kyle O’Quinn in 2012, Kenneth Faried in 2011. We’ve seen these “Hello, world!” games a lot over the years.

The key similarity that DeVries shares with some of these past examples is the fact that he’s a capable closer—he’s a dynamic shot creator who can get to his spots in a variety of ways. He loves to operate at the elbows with jab steps, bumps, and leaning jumpers, or, with his great size at 6-foot-7, go over the top if necessary. One of Drake’s bread-and-butter crunch-time actions has him come off a pindown in the left corner and either attack his man from a standstill in single coverage or roll into a ball screen from his behemoth buddy Darnell Brodie. Don’t be surprised when you see this in the NCAA tournament, starting on Thursday against Washington State.

DeVries had a pretty wretched game against Miami in the first round last season, seemingly sped up and bothered on shots he normally cashes. The difference this time around is that he’s creating more of those shots for himself. He came into college as a movement shooter who hurt teams when they lost track of him, but he’s gradually transitioned into more of an on-ball role and has really grown in his ability to dictate the terms of how and when he creates his own offense.

Tucker’s overall speed coming off of screens made me skeptical he’d ever be the type of movement shooter who exists solely for that purpose on the court, but I’ve liked how he’s blended his shooting with more reps as a methodical decision-maker who gets to his spots and finds teammates when they have an advantage. This season, 23.9 percent of his offensive possessions were in the pick-and-roll, which is up significantly from 15.6 percent a year ago. And, of course, when he’s stepping into his shot, DeVries is a stone-cold killer who shoots 45.7 percent off the dribble from 3.

Overall, the East region is a bit daunting, but in Drake’s pod, one could imagine a script in which DeVries emerges as a hero. And keep an eye on his teammate Conor Enright (44.3 percent from 3 this season), a sleeper pick for a smaller trey-slinger who could plunge a surprise dagger at some point this March. Big Edert-Farokhmanesh vibes there.

Jalen Blackmon, Stetson

Bit of college hoops trivia for those who (pathetically but admirably—and I’m including myself in that) are so inclined: Jalen’s older brother James was a marksman for Indiana from 2014 to 2017, and James Sr. was a four-year player on some strong Kentucky teams in the mid-’80s. In Jalen, the Blackmon family legacy of shooting the damn thing has continued.

The youngest Blackmon is one of the more consistent and dynamic 3-point shooters in the tournament field. As many college players do these days, he followed the playing time and it paid off, to the point where I have to wonder where the disconnect was at Grand Canyon in the first place. I mean, Blackmon came very close to posting a college 50/40/90 this season for Stetson. I know the Lopes had a good season, too, but did they not need that?

A lot of Blackmon’s damage comes without him even having to put it on the deck. He makes a living off staggered baseline screens (also known as “floppy action”). Rather than dust defenders with outright speed, he uses angular cleverness to evade them, and he has a good sense for when to fade backward and when to simply beeline to the ball off a pindown. He’s one of the most prolific and effective off-ball scorers in college basketball, as he’s in the 95th percentile for the number of those actions logged and shoots a ludicrous 47.5 percent from 3.

That said, Blackmon is the overwhelming focal point of what Stetson does, and as dynamic as he might be doing the thing he loves to do most—shooting the ball—his game doesn’t exactly sprawl into other areas. If not taken seriously, Blackmon’s movement will strain the defense that he’s facing.

I wrote this blurb before two things happened: First, he dropped 43 points on Austin Peay in the Atlantic Sun championship game. Self back-pat on that one; you’ll just have to take my word for it. Second, Stetson drew UConn, which not only plays a similar style but also has extensive defensive personnel on the perimeter—Tristen Newton, Cam Spencer, Stephon Castle, Hassan Diarra—to make this a long day for him.

Riley Minix, Morehead State

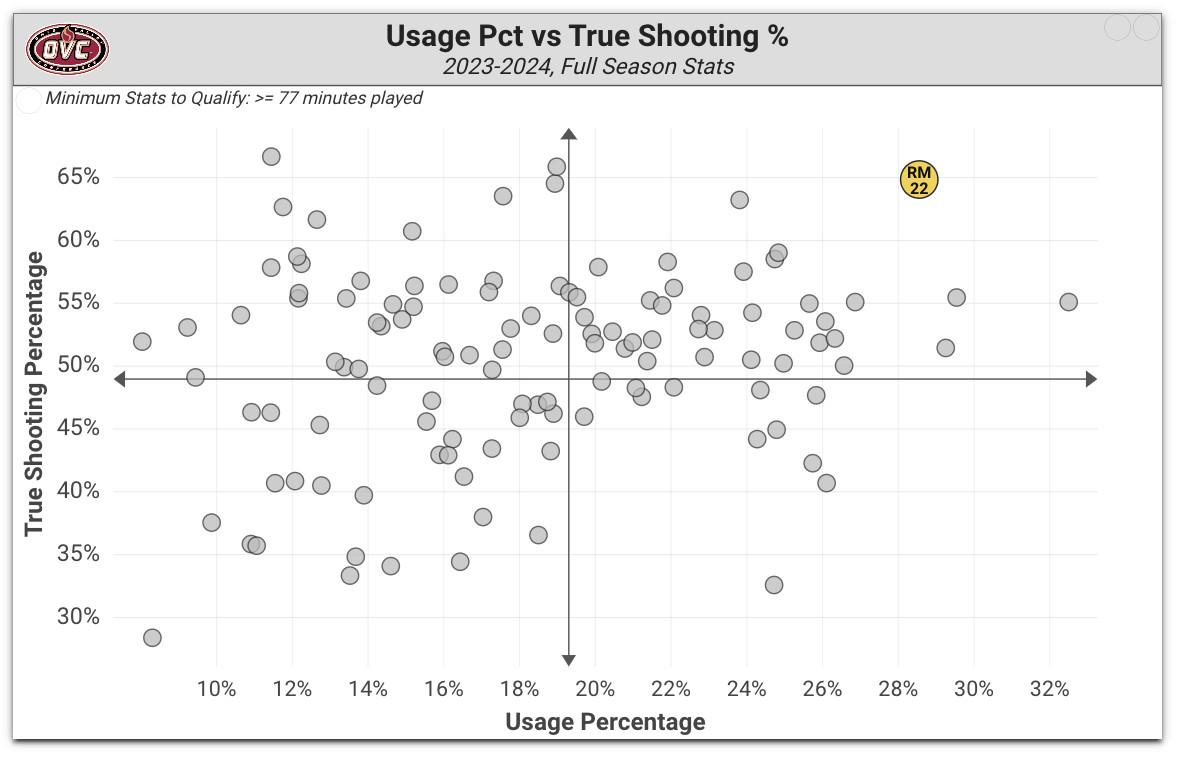

Minix the Menace is a fascinating case of talent that really translated. He’s a fifth-year grad student who spent his first four college seasons at Southeastern University in Florida, at the NAIA level, and his game interfaced with Division I better than anyone could’ve hoped. The OVC Player of the Year was the most efficient high-usage player in the conference by a wide margin, with a shot repertoire that comes at you from a variety of angles.

Minix’s most fundamental trait is that he has a painstaking (and pain-administering) offensive game that is just unusual enough to cause discomfort for bigs and guards alike. He’s capable of making something happen at all three levels, and he’s relentless in the way he finds and utilizes space. In the last 10 games of the season he shot 37 percent from 3 on nearly 5.5 attempts per game, and he’s surgical in the midrange and especially in the post. When Minix seals people, he seals people. Like, into a tomb. If he’s allowed to play to his whims, frequently on the left block in the short corner, he loves to bury people and then spin baseline before quickly getting to his right hand. Once that threat is established, he’s shown that he can do a lot with his advantage—he passes well out of the post with either hand and does some nice things when dropping off to teammates around the rim.

He’s able to do that because he has the lower body of a mule. Speaking of mules: I once saw what was proclaimed as the “World’s Largest Mule” at the Kentucky State Fair. His name was Apollo. (I never Googled it until just now, but apparently this claim was confirmed by Guinness. Gigantic specimen.)

So I walked onto this concourse where Apollo was chilling, about 25-ish feet away, and Apollo decides he has to sneeze—a huge, bellowing sound from what I have to imagine is a cavernous sinus cavity in this animal’s head. He rockets a loogie the size of a GameCube disc across the concourse and directly into my face, and I felt like I’d been attacked in the worst Alien sequel ever. Got a huge laugh. I was pissed. However, in the fleeting moments before Apollo did something to me that I would write about like, I dunno, 30 years later, I was struck by how inconceivably big and powerful his legs were.

Minix hasn’t sneezed on me yet, but I’ve felt a similar sense of amazement as I’ve watched him (not trying to continue the mule thing here but might as well) treat the paint like a field that needs to be plowed.

Illinois is a tough draw for Morehead, because I suspect we’ll see the size and versatility of Coleman Hawkins on Minix, and on defense he’ll be dealing with Hawkins and Dain Dainja, both of whom will have a noteworthy size advantage.

Achor Achor, Samford

It’s late at night in the Westchester suburbs, and Rick Pitino is sitting on the toilet with his AirPods in, hiding from Joanne. He’s got the iPad (probably an iPad Pro because the Ricktator has money) out, and Synergy is pulled up, but he’s not watching St. John’s—no way. He hates his team. This has been the least enjoyable experience of his life! No, he’s watching the Samford Bulldogs, the team that makes him feel young again.

Thanks for entertaining that bit of fan fiction, which came to me as I watched Samford this year. With their relentless pressure and the appetite for 3s that it creates, the Bulldogs remind me of those early-’90s Pitino teams that hit people with their relentless guerilla system shock of a style. Those who oppose the idea of a 24-second shot clock in the NCAA often say that college players aren’t skilled enough to play efficiently at that speed. Samford coach Bucky McMillan’s philosophy more or less counts on that, because this team—which presses on nearly 40 percent of its defensive possessions, the highest rate in the tournament field and second highest in the country—wants to either turn you over or force you to begin your offense with 23 to 25 seconds on the shot clock. That has turned Samford into one of the most annoying teams in the country to play (5-foot-7 Dallas Graziani will charm the nation with the way he pressures the ball like one of the aerosol-huffing road warriors from Mad Max), something that I’m sure the hobbled Kansas Jayhawks are giddy about as they attempt to pull themselves together for this first-round matchup.

Within this oil-and-water juxtaposition of styles, I think we could get an interesting matchup between the tireless Achor Achor and the KU frontcourt duo of KJ Adams and/or Hunter Dickinson, assuming he plays. Achor is a capable pick-and-pop threat but also does his work quickly as a screener when he heads toward the rim. While he’s a real threat to score, his role on defense is almost more fascinating to watch and the thing that could surprise a national audience. He thrives when he’s lurking at the back of Samford’s pressure and acts almost like a goalie, tending the space inside the arc when teams do break through with their sights on the rim.

Marcus Tsohonis, Long Beach State

Tsohonis has been on quite a ride. He entered college as a part of that memorable Washington recruiting class in 2019 that featured two studs in Isaiah Stewart and Jaden McDaniels (now both in the NBA) as well as journeyman (hilarious that college players can be legitimate journeymen these days) gunner RaeQuan Battle. After two seasons in the rotation and decent production, he bounced all the way to the Eastern time zone for a single season at VCU, only to trek all the way back west to play for Dan Monson at Long Beach State.

When your highest-usage player is a score-first guard, your success will rise and fall with whether their shots are going down. That’s not the sole source of blame when it comes to Long Beach’s up-and-down season, but Tsohonis is a textbook streaky scorer, and after a brutal stretch from 3 in the middle of the nonconference schedule up through the middle of January when he couldn’t throw it in the ocean (despite being right next to it), he found a rhythm at the perfect time. Long Beach was 10-10 in the WCC and had informed Monson that he wouldn’t return as head coach next season before popping off three straight wins in the conference tournament and making it to the dance.

Tsohonis can fill it up when he’s in a lather, even against high-quality opponents. He hung 35 on the road at Michigan and 28 on USC. He does that by being primarily a midrange maniac—if he turns the corner on a ball screen or finds a path to the rim, more often than not he’s stopping short and taking a floater. His 104 floater attempts rank seventh in the country, and the only players in this tournament who’ve taken more are Boo Buie from Northwestern, Don McHenry from Western Kentucky, and Wade Taylor IV from Texas A&M.

Isaiah Stevens and Nique Clifford, Colorado State

Keep an eye on the chain reaction between these two against Virginia in the First Four as they battle for the 10-seed and the honor of facing Texas and Rodney Terry’s stylish frames in the first round. This is not the team I would prefer to see if I were a Longhorn.

Stevens has used his five years at CSU to become the school’s all-time leader in points, assists, made 3s, ([ahem] turnovers), steals, and free throw percentage, just to name a few. He has played in the NCAA tournament one other time, in 2022, when he was running alongside David Roddy and they fell 75-63 to Michigan. He strikes me as more of a bucket-getter/shotmaker type than a pure shooter, but when it’s going in, who gives a shit? His game is predicated on scoring off the bounce, and his ability to create separation one on one by getting low and sharply changing direction is the kind of Kemba quality that we’ve seen pop in this tournament. That fact is especially interesting because of how well he balances that with sharing. Despite averaging 16.5 points per game, he still manages to be in the 96th percentile in assist-to-usage ratio. He does a good job of looking for his offense without outright hunting it at all times.

The poorer the ball pressure, the more teams are in rotation and helping to account for Stevens’s driving game, and Nique Clifford is frequently the beneficiary of that. Clifford is a senior transfer from rival Colorado (I’m sure that went over well, considering how well these two schools get along, as I found out on Twitter once) with great perimeter size at 6-foot-6 and a skill set that relies on having the table set for him. He’s been one of the more lethal catch-and-shoot players in the country this season, shooting 46.8 percent from 3 on spot-up looks, and that size helps to offset the fact that his mechanics aren’t exactly lightning fast. Turning him into a creator and a decision-maker is key for limiting his effectiveness.

This Colorado State team had a stretch in late November when it beat four high majors in a row in Boston College, Creighton at a neutral site, Colorado (yeah baby, go Rams), and Washington before losing to Saint Mary’s by only three a few days later. Stevens averaged 17.5 points and 7.8 assists per game and shot 42.9 percent from 3 during that stint. They won’t be surprised by anything that Virginia brings to the table, and it would not shock me at all if the Rams win that game—and maybe a couple more.