The two best defenses remaining in the playoffs are in the AFC.

There isn’t much of a debate about this. The Baltimore Ravens and Kansas City Chiefs defenses are fourth and ninth, respectively, in success rate. While the 49ers long had a great unit, and certainly still have splashier names, they’re 20th; the Lions are 17th. By expected points added per drive, the Ravens and Chiefs are second and fifth—neither NFC unit cracks the top 10.

The stories behind each defense are incredible. The Chiefs unit, which I wrote about in the midseason, is the youngest defense in the league by snap-adjusted age. All of that hype for the Jordan Love Packers and their offensive youth equally belongs to the Chiefs unit, captained masterfully by longtime NFL defensive coordinator Steve Spagnuolo. It’s got multiple bona fide stars on the roster (Chris Jones, L’Jarius Sneed, Trent McDuffie) and unbelievable, home-brewed depth (Nick Bolton, Willie Gay, Leo Chenal, George Karlaftis, Mike Danna, Jaylen Watson, Joshua Williams, Chamarri Conner). All those players were drafted and developed by this staff.

The Ravens unit, which is perhaps the best in the league, is less a story of talent discovery and more about coaching discovery: Second-year defensive coordinator Mike Macdonald, long an assistant in Baltimore, has proved to be a revelation. With tons of resources invested in traditionally non-premium positions—linebacker, safety—and bargain buys at the hallmark spots like cornerback and edge rusher, this defense has been dominating top opponents.

Besides the fun narratives, at first blush it doesn’t seem as if there’s much linking the Ravens and Chiefs defenses. Sure, their results are similar: The Ravens and Chiefs are top two in the league in total sacks and top two in the league in explosive pass rate surrendered. But schematically, they’re different units. To stop those deep passes, both run more split-safety coverages than single-high coverages, but the specifics there are pretty different: The Chiefs live in Cover 2, while the Ravens play a lot of Cover 6. To get those sacks, the Chiefs blitz on 29 percent of dropbacks (above average), while the Ravens blitz on only 20 percent (below average).

Despite those differences, the two defenses share one defining characteristic: how well they defend pre-snap motion. Per Next Gen Stats, when facing snaps when the offense uses motion, the Ravens defense is first in EPA per play; the Chiefs are sixth. The Ravens are second in yards per play surrendered on such plays, and the Chiefs are sixth.

Looking at plays with just pre-snap motion can give us a weird sample. But if we look at how these teams matched up against offenses whose entire philosophy is built around pre-snap motion, we can get a better picture of just what Macdonald and Spags have been able to achieve.

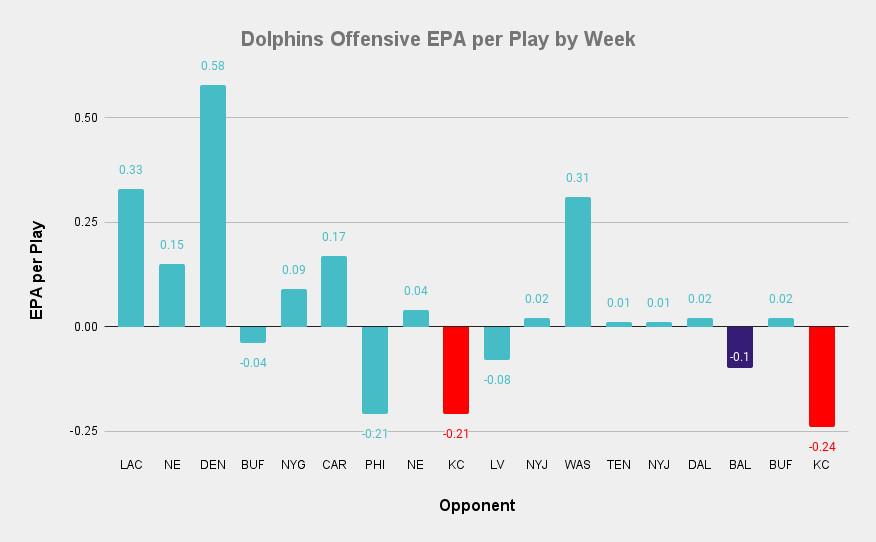

The Miami Dolphins led the league in pre-snap motion rate—they were the only team in the league to send a player in motion on more than 80 percent of their offensive plays. Here’s their EPA per play by game this season, with their games against the Ravens and Chiefs highlighted.

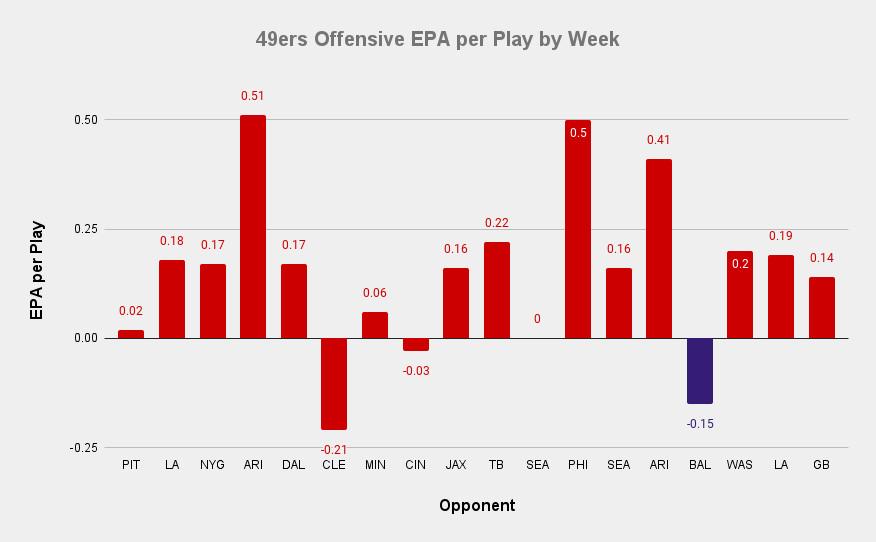

Here are the 49ers (second in pre-snap motion rate). They played only the Ravens this year, and that game is highlighted.

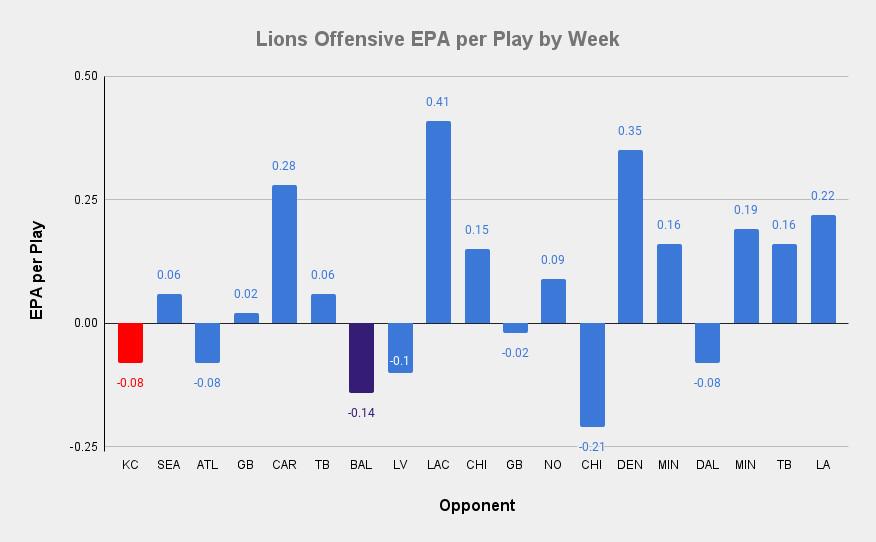

Here are the Lions, who played both the Ravens and the Chiefs and who are fourth in pre-snap motion rate.

The Dolphins, 49ers, and Lions all had top-five offenses this year by EPA per play. Against Macdonald and Spagnuolo, they crumbled.

It is worth noting that this was not a universal phenomenon. The Packers, who are another top team in motion rate, had their best offensive game of the season (by EPA) against the Chiefs defense in December; the Rams, who use motion nearly as much as the Niners and Dolphins do, hung 31 on the Ravens defense, which had stopped those other two units. If there were an easy button for defense to press against motion, all defenses would have pressed it a long time ago. But the Chiefs and Ravens are two of the only defenses that have found a way to make pre-snap motion hurt not them, but the offenses trying to use it.

Motion is the defining wrinkle of the past five years of offensive innovation, and it sure is a doozy. As Seth Walder of ESPN Analytics shared, an average NFL team snapped the ball with a player in motion on 4 percent of their offensive plays in 2017; in 2023, that average is 22 percent. That particular flavor of motion—the kind that is still happening the moment the ball is snapped—is particularly nasty. According to Walder, in 2019, runs with motion at the snap generated .11 EPA per play more than runs without pre-snap motion; for plays with dropbacks, the difference was .08. To put that in more concrete terms: Over 100 running plays, you’d expect to score 11 more points with pre-snap motion than without.

To understand why motion at the snap is such a cheat code, we need to define how a defensive play is called. An offensive play call is easy to understand—well, not easy. Just ask a young Chris Simms as he tries to relay a call from Jon Gruden.

But while “green right X, shift to viper right, 382 X-stick looky” is a garbled mouthful to those who don’t know the code, that entire play call is fairly static. The words define the formation, the motion, the route concept, and even the finer adjustment of the individual players. When the offense leaves the huddle, the players know that they’ll do green right X, shift to viper right, 382 X-stick looky—again, whatever that means.

Defenses don’t break the huddle with that certainty. They are in a reactive position. When the offense puts its personnel in the huddle—one running back, one tight end, three receivers—the defense sends in 11 defenders to match them on the field. And the positions aren’t the only thing that matter—the particular offensive players affect the defensive personnel, too. The defense will expect a run when Gus Edwards and Patrick Ricard are the RB and TE in the Ravens huddle; when it’s Justice Hill and Isaiah Likely, a pass feels a little more … likely.

But you haven’t even seen a formation yet, and you still must get a defensive play call in. Accordingly, defenses call in a front (so that the defensive linemen know how to line up) and a coverage (so that the back seven knows who’s doing what), along with any stunts or blitzes the defensive coordinator would like to call. And then they wait for the offense to break the huddle.

The offensive formation will dictate who lines up where. This is where things like “strong” and “weak” side of the formation become important. In certain defenses, players will line up on either side of the field based on offensive strength. For example, the strong safety will go to the side of the offense that the defense has defined as the strong side—the side the TE has lined up on, perhaps, or the side with three wide receivers. In other defenses, certain players will remain on the left or right no matter what but still must know whether they’re on the strong or weak side, as it will change their responsibilities—see Bengals pass rusher Trey Hendrickson, who took 736 snaps this year on the defense’s right, and two on the left.

Not only does the offensive formation dictate who lines up where on defense—it also changes the call that was just given to the defense. Consider the 49ers offense. With their standard personnel on the field, they can line up in an empty formation …

… and with the same personnel on the very next snap, get two bodies in the backfield in a condensed set.

The 49ers will run a different type of play in each formation—of course they will. (You can’t really hand the ball off in empty, can you?) So a defense will have an “empty” check baked into every call. If the offense is telling you before the snap that it won’t hand the ball off, don’t you want to adjust your call to prioritize the pass rush and maybe run a more complex coverage that takes advantage of the fact that your linebackers will be free from a run/pass conflict?

An empty formation isn’t the only thing that ignites a check. In fact, I would say just about everything warrants a check. You hear about these on broadcasts all the time: stacks, bunches, trips, tight alignment—that’s just wide receiver stuff. A defensive call can in turn change whether a tight end is lined up on the ball, or whether he’s a step off the ball, or whether he’s in the slot instead of attached to the tackle; whether the running back is next to the quarterback in the gun and then steps to the other side of the quarterback in the gun, or whether he steps behind him to get into the pistol.

You can imagine the strain on a defense’s communication. The offense breaks the huddle, and linebackers are barking out the strength of the offensive formation so that everyone can get lined up. Meanwhile, each side of the secondary is communicating both with the other side and among themselves to define the coverage—it’s Cover 3, but we’ve got a trips set over here, so we’re running Skate.

While the offensive plans are generally static—no matter what the defense runs, X receiver is running a post—the defensive plans are fluid. Against one formation, they’re covering that post with man coverage and a deep safety; if the formation changes, the coverage check changes, and all of a sudden they’re zoning it off, passing it from one player to another.

And that’s where pre-snap motion comes into play. The defense calls their strength and their check when the offense sets into a formation … and then the offense moves. And the defense has to reset the coverage on the fly.

The offensive abuse of pre-snap motion, and especially motion at the snap, leads to some hilarious coverage busts. One of the most popular motions today is the fast-out motion popularized by Mike McDaniel’s offense in Miami. Not only does it allow a speedy receiver to move at full throttle at the snap, but it also creates a new outermost receiver at the snap, which changes the coverage responsibility of every single defensive player.

It’s easy to see why offenses are using motion at unprecedented rates. Motion isn’t without cost—motion-heavy teams can struggle on the road, where loud opposing environments make it challenging for them to time up their snap count, and some quarterbacks prefer reading a static defense, instead of one moving at the snap—but the costs are dramatically outweighed by the gains.

At least, against most defenses. But the Ravens and the Chiefs have discovered a counterpunch.

Remember, there aren’t too many shared threads between the Ravens and the Chiefs schematically. It’s not that they’re both leading the league in press man coverage or blitz rate or something like that. There is, however, a significant philosophical similarity between Spagnuolo and Macdonald: They both want to change the picture.

Just as offenses can move a player to change their alignment pre-snap, so too can defenses—in fact, all of the defensive players can move, at the same time, pre-snap or at the snap, in any direction they want (that is, behind the line of scrimmage). This edge is one that Spagnuolo has maximized during his five seasons as the defensive coordinator of the Chiefs and for his many years of coaching defense before that. Spags rotates coverages as much as any defensive coach in the league, spinning from two-high to one-high or from one-high to two-high, dropping a cornerback to a zone typically filled by a safety and a safety down into a zone typically filled by a linebacker. What’s that linebacker doing, you ask? Usually blitzing.

Rotating coverage can be hard. You need versatile players to pull it off. Guys like Justin Reid, a safety who is as comfortable fitting the run between the tackles as he is playing a deep half against speedy receivers, or L’Jarius Sneed, a college safety turned slot corner turned outside corner who can rely on his experience at other positions to take on new coverage responsibilities at the drop of a hat. You also need excellent communication on the field as seven players move in concert, and you need excellent coaching to get these plays installed.

While Spagnuolo has been doing it for a long time, Macdonald, a league sensation and huge name on the head-coaching market, has less experience. When Spagnuolo was the defensive coordinator with the Giants in 2008, Macdonald was the linebackers and running backs coach at Cedar Shoals High School in Georgia. By the time Spagnuolo had gotten his first head-coaching job, lost it, and landed on the Ravens staff as their secondary coach in 2014, Macdonald had broken into the league. He was on that 2014 Ravens team as a coaching intern. You can’t help but wonder what pieces of Spagnuolo’s approach stuck with a young Macdonald as he watched Spags from afar or got his ear for a few precious minutes.

However Macdonald’s defensive philosophy was concocted (he coached under two legends, Dean Pees and Wink Martindale, for much of his time in Baltimore), his defense wants to accomplish the same goals that Spags’s does. He wants to change the picture.

Unlike the Spagnuolo defense, which sends a lot of true blitzes—that is, sends an extra rusher (or two, or three)—the Ravens defense with Macdonald likes to simulate blitzes. They’ll send a safety or a nickel or a linebacker, but in exchange, they’ll drop a pass rusher off the line of scrimmage and into coverage. This world of simulated pressure is a modern twist on the enduring problem of NFL defenses: How do we affect the quarterback? By sending surprising pass rushers, you can beat protection rules and get quick pressure—but by dropping surprising bodies into coverage, you can also muddy reads and force quarterbacks to hesitate. Simulated pressure can offer much of the advantage of blitzing, without as many of the drawbacks.

Just like in Kansas City, unique players are required in Baltimore for this defense to work. It was not a coincidence that, once the Ravens installed Macdonald as their coordinator, they spent a top-15 draft pick on a supersized safety in Kyle Hamilton and traded a second-round pick for a star middle linebacker in Roquan Smith. At pass rusher, the Ravens deploy a unique athlete, Jadeveon Clowney, and the notoriously versatile Kyle Van Noy, both acquired as free agents this year.

It’s not just defensive pieces that you need. You also need excellent coaching to make it as easy as possible for all 11 players to get on the same page. You need excellent advanced scouting to riddle out your opponent’s protection rules and prioritize pressures that will beat them.

But the “what” and “how” of defensive picture changing aren’t, well, the whole picture. There’s also the “when” of the call—the precise moment when all of those players move in concert, each filling the space that was just vacated by a teammate. Poor timing in defensive rotation creates cracks in the shell, windows in the zones—space in coverage that a quarterback, even when disoriented, can exploit. Ideally, the coverage starts to rotate just as the ball is snapped so that defenders are already flying in motion when the quarterback goes to make his reads. But you don’t always know when exactly the ball will be snapped.

… unless you’re playing one of those teams that uses motion all the time. Then you can be pretty sure when the ball will be snapped.

And that’s why these two coaches have found such success against the motion teams. It’s not a new defensive structure, x’s and o’s arranged in a constellation undiscovered by humankind; it’s not a new technique or coverage. It’s just knowing when the ball will be snapped.

Watch this pressure on the first drive from the Chiefs game against the Dolphins. On a clear passing down, the Chiefs have three safeties on the field, and because they’re confident the Dolphins will snap the ball with motion, they don’t need to be clearly set right as the offense gets to the line. Watch how the entire Chiefs secondary instantly reacts the moment the Dolphins send Tyreek Hill into motion.

That silly little motion—Hill is squatting in a tight end’s position, then suddenly scoots to become the new outside receiver in what has become a bunch set—is supposed to break a defense’s collective brain. We’ve seen it happen across the league, week after week. But against the Chiefs, all the Dolphins have done is activate Spagnuolo’s trap card. His blitz swallows up the protection, and the backside cornerback gets a great jump on his pressure, which Tua Tagovailoa never sees coming. There was an open receiver beyond the sticks, but it didn’t matter—the quarterback is sacked, and the ball is punted away.

Contrast that play with this one—another third-and-9. Here, the Dolphins don’t motion anyone, and the Chiefs’ intentions are easier to anticipate. The Chiefs blitz and rotate on the snap signal from the guard, but the timing is off, and they’re almost offside. The blitz still gets home—Tua knows he’s hot and has to throw underneath, and the pass is dropped—but the operation isn’t as clean.

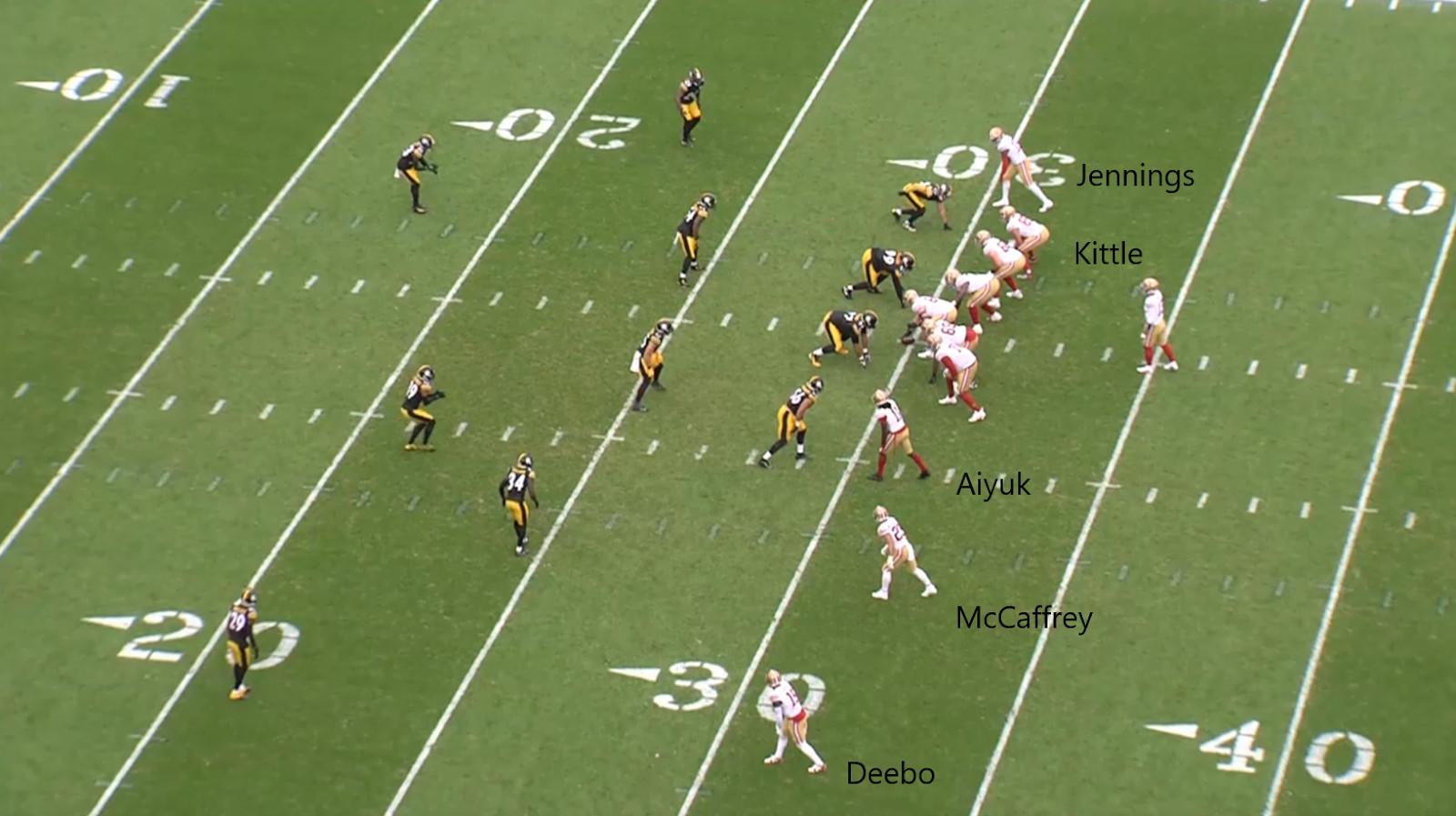

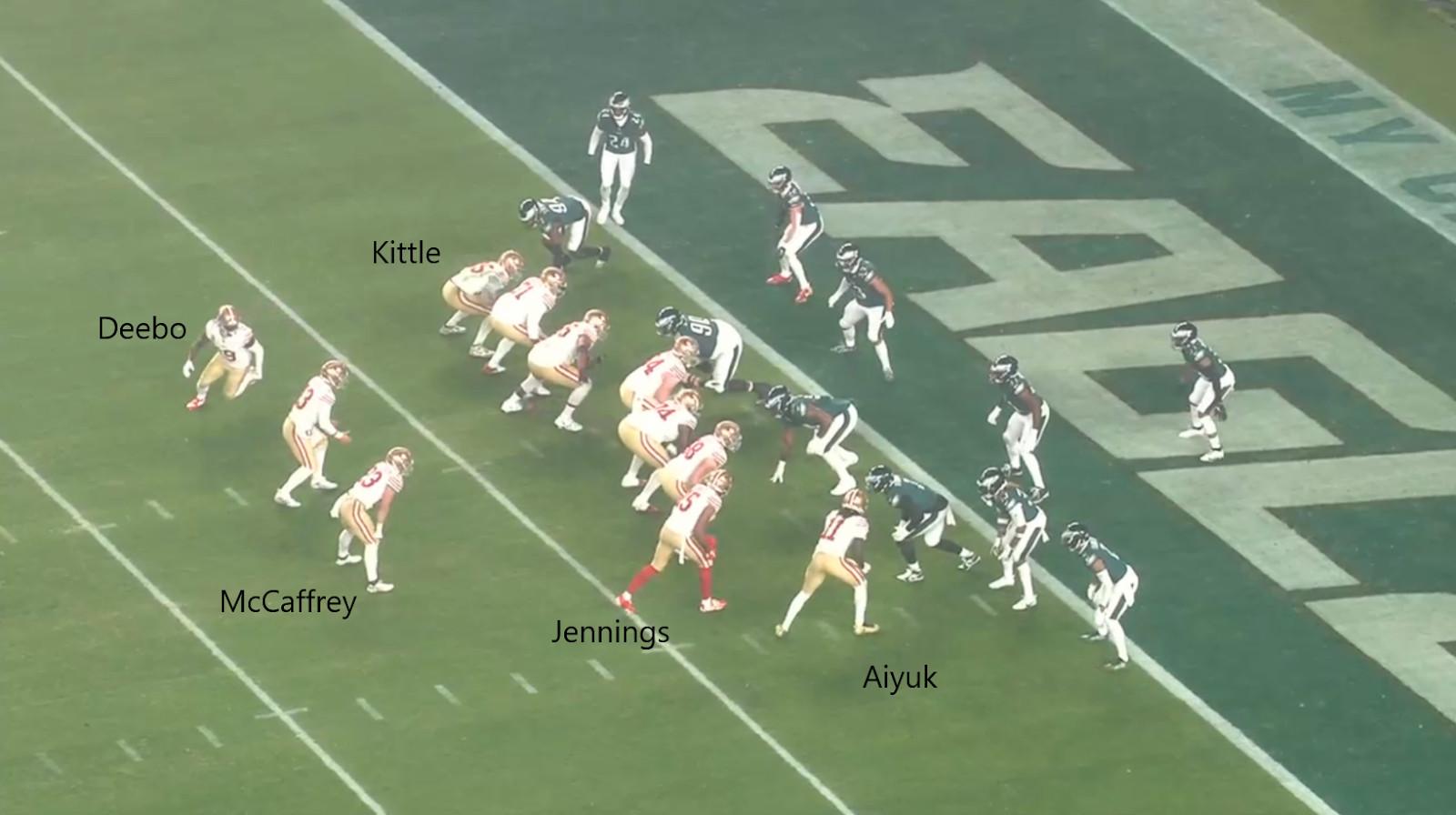

Once you see how the offense’s motion tells the defense when to move, it’s hard to unsee. Here’s the very first play of the 49ers offense against the Ravens defense. As Christian McCaffrey leaves the backfield, linebacker Patrick Queen slips down to the line of scrimmage and comes screaming off the edge with momentum; Smith and the backside corner adjust their alignment to account for his absence. Quick pressure, checkdown forced.

Here, Ravens nickel corner Arthur Maulet times up his own blitz off the same Hill motion that we saw the Chiefs beat above.

And here comes Maulet once again, this time against the Lions as WR Jameson Williams comes in motion across the formation. The blitz is cool, but watch at the bottom of the screen as Queen is able to easily navigate the natural pick from the tight end and get into coverage over the running back. How? He moved just before the snap because he knew when it was coming—the motion told him.

This isn’t just a nifty thing to see on film. Whichever team ascends to the Super Bowl will be facing either the 49ers or the Lions—offenses that are top five in motion rate that have suffered when they played these defenses in the regular season. The cream rises to the top, and it is no mistake that these two defenses are the ones vying to represent the AFC: They are the cream. They are the standard of NFL defending.

Elite defense isn’t just about what you can do against league-average offenses; it isn’t just how well you can build an elite four-down pass rush and bully your way to a couple of sacks and turnovers. Defense is about responsiveness, adaptability. As the prevalence of pre-snap motion has made offenses into moving targets, defenses must be capable of responding. If you can’t deal with this style of offense, which is ripping through the league like wildfire, then you cannot make a postseason run. Eventually, you will bump into some chaotic offensive coordinator who’s launching his wide receivers hither and thither, you will give up 40, and your head will still be spinning on the flight to Cancún.

Of course, it matters for this week, too. The Ravens are sixth in the league in motion at the snap—they use it to nasty effect in their running game, to mess with your fits and involve Lamar Jackson in the option game. But with careful film study, Spags can now dial up run blitzes with impeccable timing. The Chiefs don’t snap the ball with a player in motion as much, but they’re still seventh in total motion rate. Patrick Mahomes uses it to get coverage reads before the ball is snapped. The disguise that defines Macdonald’s defense must discombobulate the greatest quarterback alive on Sunday—no small task.

But after this weekend’s game is played and a championship is crowned a few weeks down the road, the play of the Chiefs and Ravens defenses will continue to ripple throughout the league. Offenses everywhere will put on their film and devise crafty new ways to mess with a defense’s plan, scrambling for a new foothold. Defenses will consider how to teach their guys to communicate, disguise, and coordinate the same way Spags’s and Macdonald’s defenses have. The cream will continue to rise to the top. Pre-snap motion was the offensive evolution. This is the defensive response, the coevolution. The scales might finally start tipping back.