I worked as an intramural basketball referee in college. I already knew the rules and needed only to buy a whistle; it was an easy way to make some extra money on campus. Or, at least, it was easy when I wasn’t reffing Brian’s games.

Brian was a student at my university’s medical school, and he was an excellent hooper. He’d been a teammate of Jeremy Lin’s at Harvard as an undergrad, then gone on to play in multiple countries in Europe and receive a cup of coffee with the Maine Red Claws (the Celtics’ G League affiliate). Most importantly for this story, he was 7 feet tall and about 250 pounds, which gave him an advantage of at least four inches and 30 pounds over any opponent who had the misfortune of guarding him.

That disparity turned Brian’s games into a nightmare to officiate. I could have called a foul on just about every one of his offensive possessions, as overmatched opponents resorted to extremely physical defense in a fruitless effort to slow him down. I tried to strike a balance between maintaining the game’s rhythm and not letting it get out of hand, but opponents—and, often, Brian himself—were never satisfied. I remember one asking with wide eyes after a whistle, “What else am I supposed to do?”

I’ve been thinking about Brian this week, ever since Steve Kerr Grinched about Nikola Jokic’s 18 free throw attempts in the Nuggets’ win over Golden State on Christmas. “I have a problem with the way we are legislating defense out of the game,” Kerr said in his postgame press conference. “That’s what we’re doing in the NBA. The way we are teaching the officials, we are enabling players to BS their way to the foul line. … They are taking full advantage and it’s a parade to the free throw line. And it’s disgusting to watch.”

Kerr’s complaint was just the latest and most prominent gripe about foul calls this season, but I’ve seen its ilk all over NBA discourse. The most common form on social media is a video of an MVP candidate like Joel Embiid or Luka Doncic, and an ostensibly soft whistle that penalizes a defender and sends the star to the line.

But I’m here to declare that this narrative is nonsense. NBA officiating isn’t perfect because of the inherent challenge of making subjective, split-second decisions as athletic marvels run into each other. (Soft technicals and ejections for, say, hanging on the rim after a dunk, flexing, or cursing are a different story.) But the current state of foul calls is far from a crisis.

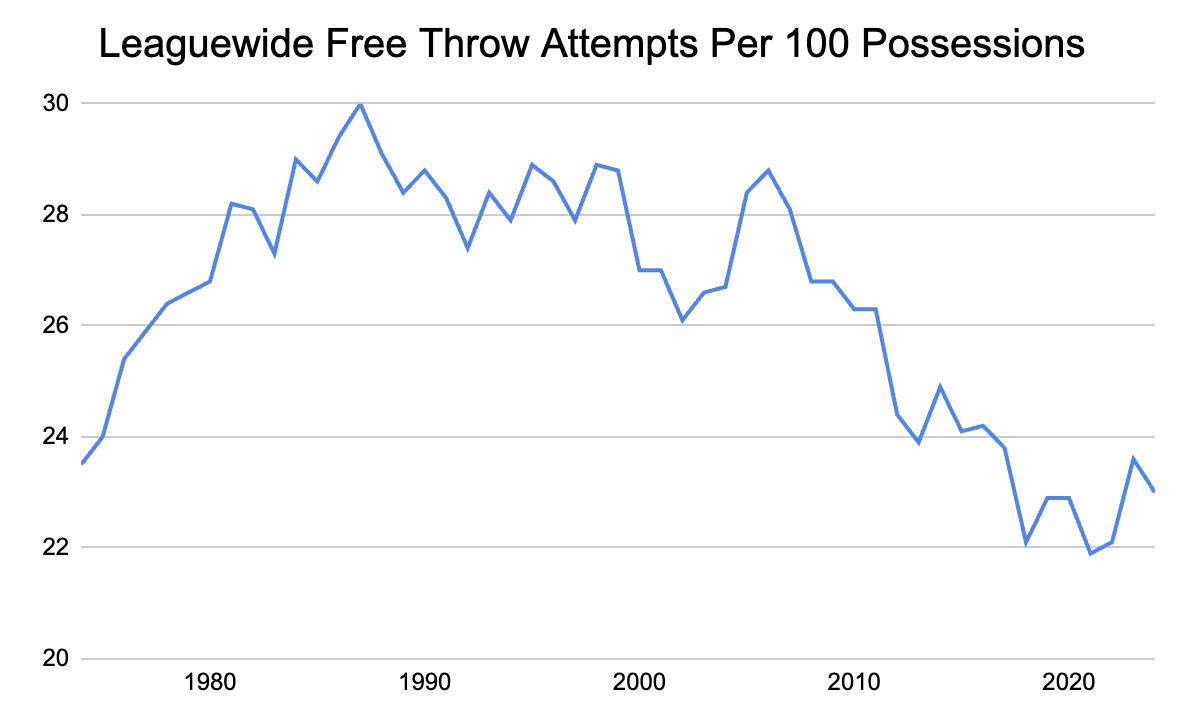

Let’s look at the concern a few different ways. First, free throws are down across the league, not up. This graph shows the number of free throws per 100 possessions leaguewide since 1973-74 (the start of Basketball Reference’s possession data). It doesn’t look like the depiction of a parade to the line.

Free throws have been on the decline for decades now. The four lowest-foul seasons on record are also the four most recent seasons. Adjusted for pace, there are 20 percent fewer free throw attempts in the 2020s than there were in the 1980s and 1990s. Put another way, Embiid’s 76ers lead the league in free throw attempts in 2023-24, but they’d be below average in the 1980s and 1990s.

Leaguewide Free Throw Attempts Per 100 Possessions

These data points aren’t the be-all, end-all to the question of free throw trends. This decline is almost entirely the result of the NBA’s 3-point boom, because 3s in space are less likely to draw fouls than 2s in a crowd.

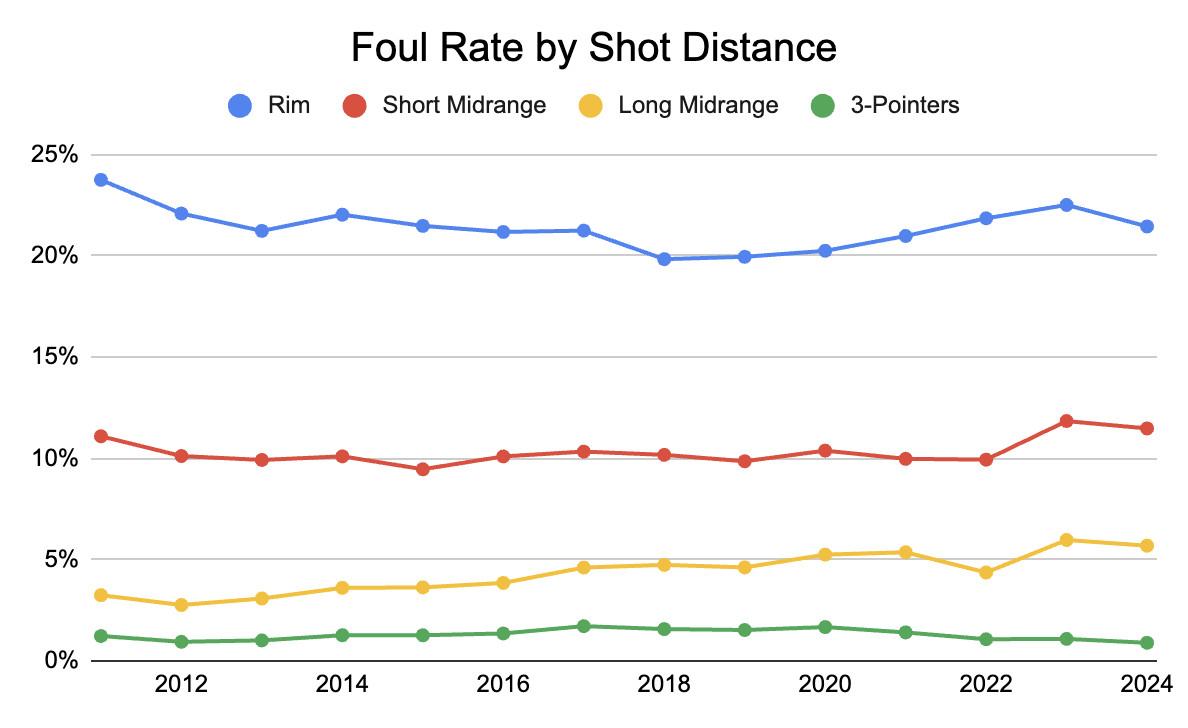

But on a more granular level, we aren’t seeing a noticeable uptick in whistles in different areas of the court. This season, 21.5 percent of attempts at the rim have generated free throws—either two shots or an and-1—according to an analysis of Cleaning the Glass data, which removes garbage time. CtG’s foul data goes back to the 2010-11 season, and in that 14-season span, the overall rate of fouls drawn on rim attempts is a nearly identical 21.4 percent.

The same basic pattern also holds true for attempts from the short midrange, where 11.5 percent of attempts this season have resulted in free throws. The overall rate on those shots since 2010-11 is 10.3 percent, and I simply don’t believe anyone who claims they can actually discern a difference of 1.2 extra fouls per 100 short midrange shots. Teams attempt about 21 short midrange shots per game, per CtG, so the difference comes out to one extra foul every four games.

(The foul rate on long midrange attempts is up the most, from 4.0 percent over the whole span to 5.7 percent this season. But long midrange attempts are now the least common shot type by far, and I suspect the foul rate increase in this area is due to a shift in the caliber of player who operates there. A decade ago, a large proportion of midrange attempts were catch-and-shoot looks from role players; now, midrange attempts are overwhelmingly likely to be off-the-dribble tries from closely guarded stars. Those demographic factors should naturally produce more foul calls.)

Moreover, non-shooting fouls that lead to free throws aren’t a growing concern, either, likely because fewer fouls overall means less time in the bonus. In the 2010s, teams had an average of 2.6 non-shooting fouls per 100 possessions that yielded free throws; in the 2020s, that number is just 2.2, according to an analysis of PBP Stats.

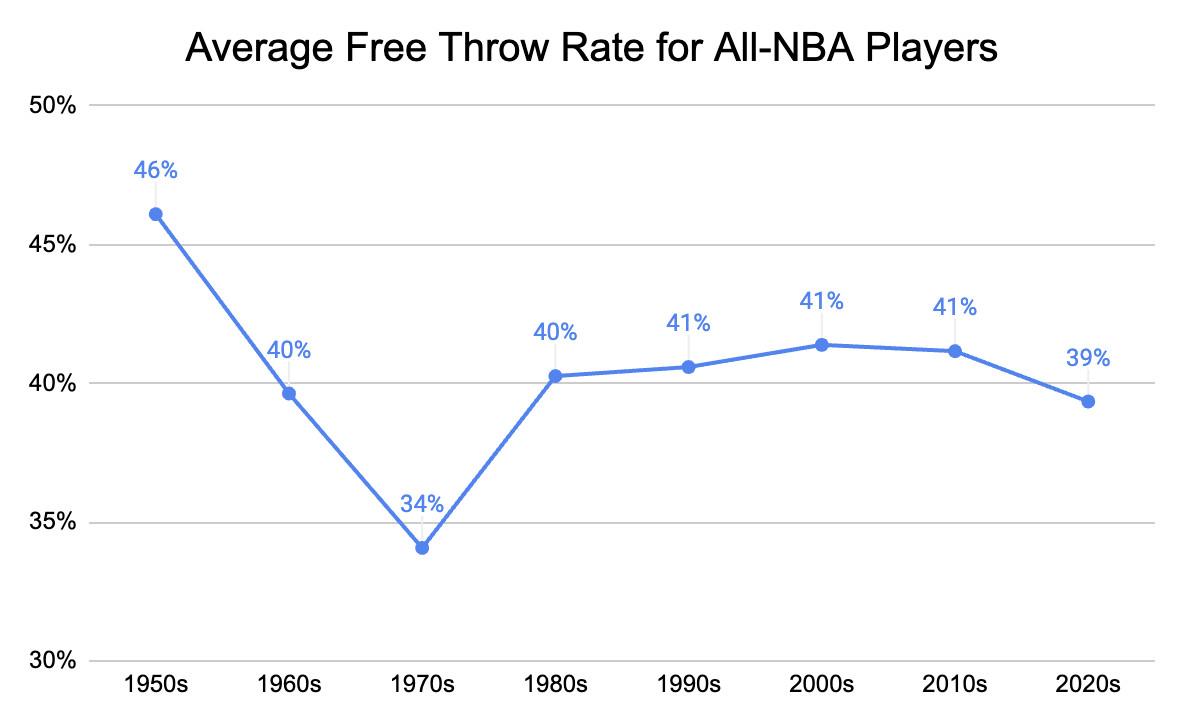

Maybe, critics might say, looking at fouls on a leaguewide scale doesn’t capture the problem; maybe fouls are limited to a group of “foul merchant” stars rather than the whole player population. But if so, that isn’t a new phenomenon for stars of the 2020s. As JJ Redick said on a recent episode of his podcast (before Kerr’s comments), “The best players have always shot a lot of free throws.”

Last season, the 15 All-NBA players had an average free throw rate of 42 percent, meaning they attempted 42 percent as many free throws as field goals. For comparison, the overall average for All-NBA players in league history is 40 percent. Modern stars aren’t receiving more calls than their predecessors did.

Granted, some stars benefit from trips to the line more than others. Ironically, given the impetus for Kerr’s comments, Jokic is a terrible example to highlight. His 18 attempts on Christmas tied a career high; 46 other active players have attempted more free throws in a game. And the Nuggets as a team rank just 26th in free throw rate this season. (They were 20th en route to a title last season.)

On the other end of the spectrum is Embiid, who leads the league with 11.6 free throw attempts per game. The reigning MVP’s free throw rate is 53 percent this season—but that’s actually his lowest individual mark since his second season, back in 2017-18. Embiid has always put on a one-man free throw parade, because, like Brian in my intramural games and Fezzik in The Princess Bride, he’s the biggest and the strongest, so defenders’ only recourse is to try to get away with contact.

The issue might seem more magnified now, coming after the relative dearth of star centers in the mid-2010s, but Embiid isn’t the only big man in NBA history to inspire this level of foul angst. Rather, he’s one of a select few who dominate the historical free throw attempt leaderboard. (This chart looks at free throws on a per-possession basis, so Wilt Chamberlain—who played before we have reliable possession data—doesn’t appear.)

Free Throws Per 100 Possessions Leaders (Since 1973-74)

What makes Embiid special, compared to Shaq, Dwight, Giannis, and Wilt, is that he’s a much better shooter than the others, making 89 percent of his free throws this season and 82 percent over his career. For comparison, Giannis is at 71 percent for his career, Howard 57, Shaq 53, and Wilt 51. At 11.6 attempts on average, the difference between Embiid at 89 percent and his peers in the mid-50s is a whopping four extra points per game.

But Embiid isn’t leading the league in scoring only because of his free throw prowess. He also leads the league in made field goals per game.

Unlike Shaq and Dwight, the best big men in the modern era are also skilled away from the rim, which heightens the challenge for defenders matched up against them. “It’s impossible to guard [Jokic] when it’s like that,” Warriors center Kevon Looney said this week. “He’s already a tough cover. He already can get any shot he wants. When you can’t really be physical with him or aggressive, you are at his mercy.”

But that’s not a problem with officiating; it’s a problem with the general structure of the sport, in which offenses get to act and defenses have to react, now with greater spacing than ever before. Defenses are already at the mercy of behemoths like Jokic and Embiid, and will be no matter how the game is officiated.

Before the Bulls’ win over Atlanta on Tuesday, coach Billy Donovan was asked about Kerr’s comments and said, about the difficulty of playing defense in the modern NBA, “I totally understand where Steve is coming from on the comment, because that was a topic of conversation, quite honestly, in our head coaches meetings in September.”

But, Donovan continued, he sees the NBA making an effort to legislate against the most egregious examples of foul-baiting. “The league has done some things to try to change,” he said. “They’ve talked about that rip-through move that everybody used to do all the time to get to the free throw line. They tried to eliminate some of this stuff when you’re coming off pick-and-rolls, when guys would stop and just try to throw shots up at the basket.”

The NBA also expanded its challenge system, implemented anti-flopping measures this season, and curbed a different sort of “disgusting” break in game flow with the take foul rule last year. It could do more still by, say, tweaking hand-checking rules on the perimeter or giving defenders at the rim more leeway with verticality. But that might be overreacting to a problem that doesn’t exist, or at the very least isn’t any worse now than it has been throughout league history. The only difference in the 2020s might be that social media has made it easier to highlight close calls that benefit stars.

Foul baiting and foul calls will always embody a sort of cat-and-mouse game. Players are smart and will seek out the boundaries of the rules to steal free points. Then the league will tinker with its rules, or instruct officials to alter their areas of emphasis, in response. That’s just the nature of the sport—from the NBA down to rec leagues to everything in between.

Thanks to Ben Falk for research assistance.