J. Robert Oppenheimer is such a fitting protagonist for Christopher Nolan that it feels written in the stars for Oppenheimer to be his first stab at a biopic. Here is another brilliant man tortured by the enormous cost his obsessive work exacts on himself and those around him: a dilemma Nolan has explored through everything from feuding magicians (The Prestige) to thieves of the subconscious (Inception) to cosmic explorers (Interstellar). Nolan’s obvious preoccupations in his films—another concerns his ongoing fascination with the concept of time—can elicit strong reactions, both good and bad, from moviegoers. For Nolan die-hards, he’s one of the most skilled big-budget technicians this side of Stanley Kubrick; for Nolan detractors, he’s something of a one-trick pony who couldn’t write a compelling female character to save his life. (Personally, I lean more toward the pro-Nolan camp, even as I fail to understand the adoration for Inception. Don’t sleep on The Prestige, though!)

Even if Nolan’s movies aren’t your cup of tea, I think we can all agree that he’s capable of producing indelible images: astronauts leaving the familiar comforts of Earth for the seemingly endless void of the universe, soldiers packed like sardines on a dock waiting to return to a home they might never see again, the Joker sticking his head out of a police car window as Gotham City descends into chaos. Nolan’s narratives can sometimes be hard to follow—I understand 30 percent of the time-bending events that unfold in Tenet, at best—but his films always demand to be seen on the biggest possible screen. (IMAX screens, preferably.) No matter what, you’re in for a genuine spectacle; whether you’ll be emotionally invested in the characters is far less assured.

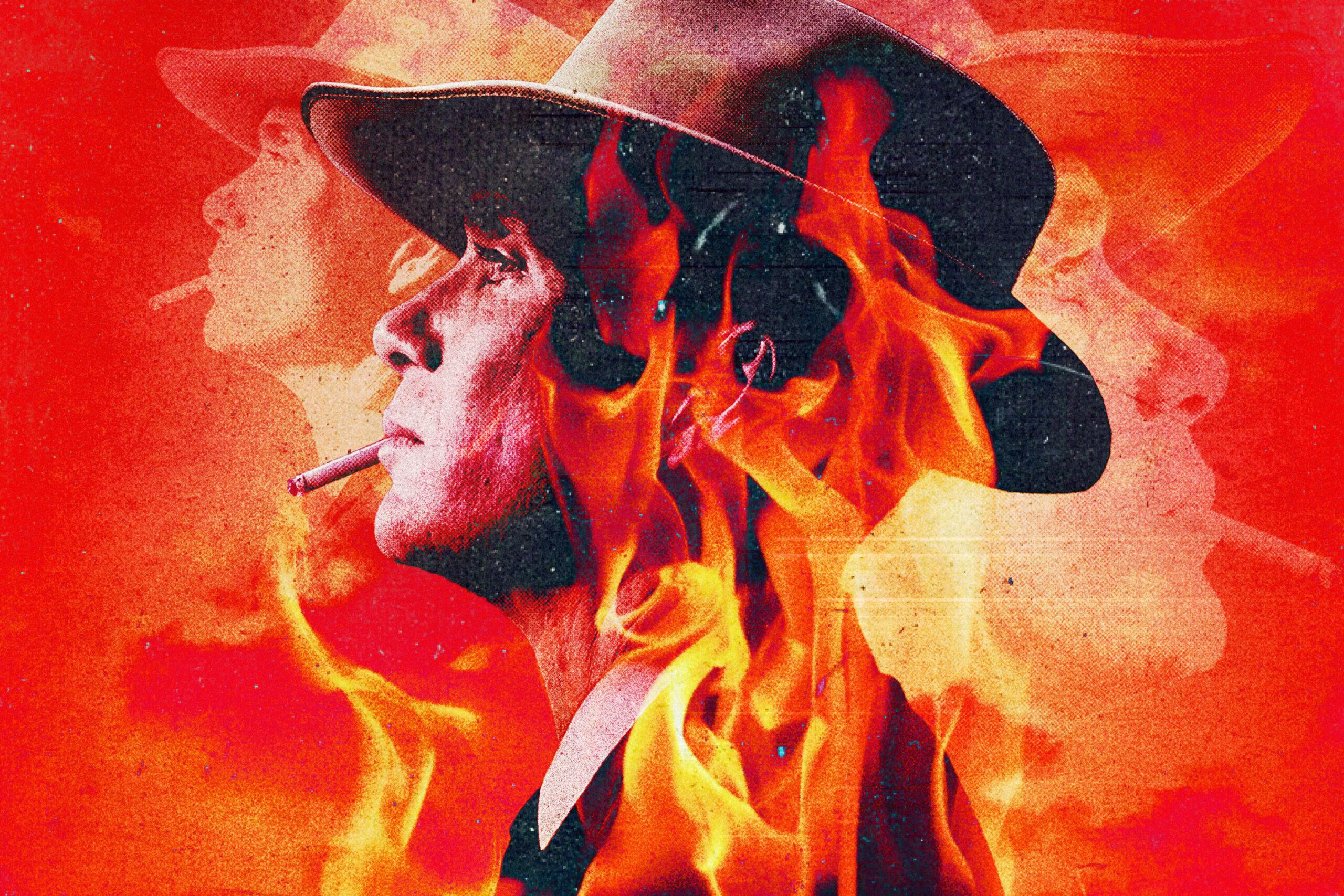

For a director with a proven track record of stunning image-making, Oppenheimer’s life and the creation of the atomic bomb offer fertile ground. (That Nolan set off real explosives for the movie was nothing if not extremely on brand.) But the paradoxical thrill of Oppenheimer is that Nolan crafts an epic tale that’s intimate in nature: a film with existential stakes that moves at the breakneck pace of a thriller despite mostly showing scientists, politicians, and military officials discussing the grave consequences of their actions. The actual detonation of nuclear weapons takes up a small fraction of the movie’s meaty three-hour running time, with the rest of the action unfolding like a chamber piece. For some viewers, that approach might feel antithetical to the Nolan blockbuster experience, but it’s that level of restraint that makes Oppenheimer the most ambitious project of Nolan’s career—daring to go small when everyone is expecting a grand display of showmanship.

To Nolan’s credit, he already has a more conventional World War II epic on his résumé. With 2017’s Dunkirk, Nolan immersed the audience in the evacuation of Allied troops from the land, sea, and sky—what the film lacks in memorable dialogue, it more than makes up for with a relentless sense of urgency. (The intense Hans Zimmer score also does a great job of elevating your heart rate.) In that respect, Oppenheimer makes for a fascinating companion piece to Dunkirk, focusing on the scientific minds back home that sought to create the world’s first atomic weapons before the Nazis could beat them to the punch. At their cores, Dunkirk and Oppenheimer are races against time during World War II—one of these events just happened to define the rest of modern history.

There is an undeniable potency to conveying the atrocities of war on the ground, but the real power of Oppenheimer is that it shows how the most fateful and calamitous decisions take place far away from the battlefield. (Watching Oppenheimer, particularly the scene where government officials brainstorm which Japanese city to bomb, I was reminded of the military higher-ups in Saving Private Ryan who ordered soldiers to risk their lives for what amounted to a cynical PR campaign.) It’s why Oppenheimer spends much of its running time leading up to the Trinity nuclear test before turning its focus to the harrowing aftermath—recreating the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki would’ve been a gratuitous perversion of spectacle. As the French filmmaker Francois Truffaut once said, all war films, to some degree, end up glorifying the very events they’re meant to admonish; Oppenheimer tries to get around that by avoiding the front lines entirely.

Which is not to say that Oppenheimer doesn’t feature an atomic explosion that’s worth the price of an IMAX ticket. The Trinity test is a sequence of truly terrifying splendor that’s all the more visceral because it didn’t require any CGI, and the gravity of that moment is enough to carry the rest of the movie. It helps that, unlike the directors of most contemporary blockbusters, Nolan trusts his audience to understand what Oppenheimer and the other scientists of the Manhattan Project have wrought upon the world without laying it on too thick. One of the most effective scenes in the entire film is a presentation about the aftereffects of the bombings in Japan—the camera never leaves Oppenheimer’s face, and Cillian Murphy bears the weight of the character’s guilt on his haunted, wraith-like expression. We don’t need to see the contents of the presentation to know that Pandora’s box has been opened. Similarly, when Oppenheimer is meant to give a triumphant speech to his colleagues and their families after the attack on Hiroshima, the stomping of the attendees’ feet in unison, which recurs throughout the movie, recalls the sound of marching soldiers: a nifty way of contextualizing what they’ve accomplished as a weapon of war instead of a weapon to end all wars.

For the better part of the last two decades, Nolan has been handed massive budgets and delivered thrilling blockbusters that double as extraordinary technical achievements. (Your regular reminder that Nolan spent $5 million on a vintage Luftwaffe fighter plane in order to crash it in Dunkirk and followed that up by doing the same with a goddamn 747 jet in Tenet.) That certainly remains the case with Oppenheimer and the startling authenticity of its atomic bomb, which will rattle your bones in the theater, but that’s not the director’s most impressive feat in the movie. Rather, it’s that Nolan created such a grim character study at the largest possible scale and came out on the other side with what already feels like the defining film of the year. Taking an understated approach to the dawn of the nuclear age is the last thing I would’ve expected from Nolan based on everything he’s done since Batman Begins, and that’s what makes Oppenheimer so exciting as it relates to his evolution as a filmmaker.

During an Entertainment Weekly roundtable, Murphy, Emily Blunt, Matt Damon, and Robert Downey Jr. were asked to name their favorite Nolan film. (Nolan was also present and answered with Dunkirk.) There’s really no wrong choice, but Downey had an interesting perspective: The best of Nolan is yet to come. “Many people will say [Oppenheimer] is your greatest film and a culmination of aspects of every film you’ve ever done,” Downey told Nolan. “So it’s almost like Good Will Hunting: You’ve made this equation where you’re now at the end of the chalkboard, and what the heck would you do next? But we believe in you, sir. So my favorite film of yours is whatever the heck you do after this, because you’d better come up with something amazing.” As much as I love The Prestige, I’m inclined to agree.