Killer Mike is nothing if not free. His musical credits, TV projects, and political activism form a fiercely and unapologetically opinionated body of work. He and EI-P have spent the past decade on a world-conquering run as the renegade hip-hop duo Run the Jewels. In the span of four albums over seven years, he’s also been a presidential campaign surrogate for Bernie Sanders, a social scientist in the limited documentary series Trigger Warning With Killer Mike on Netflix, a talk show host in syndication on PBS, and a rabble-rouser at city council meetings, along with his friend 2 Chainz, in their hometown of Atlanta.

On Friday, Killer Mike is releasing Michael, his first solo album in more than a decade. The album, produced by No I.D., is a bighearted gospel crossover with an impressive roster of collaborators, including André 3000, Future, Mozzy, Dave Chappelle, and, of course, El-P. Killer Mike spoke with The Ringer about growing up in the church, digging deeper into his darkest feelings with No I.D., and negotiating the race and class dynamics of hip-hop that often rile both artists and fans.

Several years ago, I had a conversation with producer London on da Track. He was talking to me about how he and his siblings were raised by his grandparents. His granddad was a minister, and all the kids in the house played an instrument in the church. London played piano.

They were the family. We belonged to a big, prestigious Baptist church on our side of town, Mount Olive Baptist Church. After Sunday school, we’d go with my grandmother to these little small Pentecostal and Holiness churches. London on da Track’s family was the kind of family I detested. The daddy is the preacher, the mama is the lead singer, the daughter is the second lead—they were so talented. After I got past my envy of those families, I fell right in the league with them, and those were my favorite churches to go to because of the amount of talent. The same people that would be playing in the club the night before—sometimes clubs that my mom went to—would be playing bass or guitar in the Pentecostal band. They were full of life. They were full of laughter. They were full of joy. They were full of reverence and sincere praise. And it was all set to some of the dopest, most badass music ever. If it wasn’t for families like this, you wouldn’t get Mario Winans, you wouldn’t get London on da Track, you wouldn’t get Whitney Houston. I’m blessed to have had that same Pentecostal experience.

Talk to me about that sort of integration. You hear it in this album. You hear it in NBA YoungBoy. A rapper might sound like a heathen on a record, but you can definitely tell the ones who grew up in the church.

Especially in the South. If you’re hearing Pimp C, you’re hearing a product of the Black church. If you’re hearing Juicy J and DJ Paul—those Willie Hutch samples, the way they jolt the sample—you’re hearing a product of the church. If you’re hearing Dungeon Family—Organized Noize are direct mentees of Curtis Mayfield—you’re hearing the soul of the Black church.

All church ain’t got good music. The Black church has great music. God got a way, and music has been the way in the Black Southern religious experience. You learn the word of God from the preacher, and if he’s a really good preacher, he’s got a voice on him. He can sing, too. I absolutely feel God’s presence when I listen to certain rap music. I said that 11 years ago on R.A.P. Music, and today, I stand more cemented in that after having worked with the cast of people that I worked with making this record. They absolutely came out of the Black church background and experience. You can hear it in the hooks. You can hear it in the bass lines. You can hear it in the organs. You can hear it in the choruses.

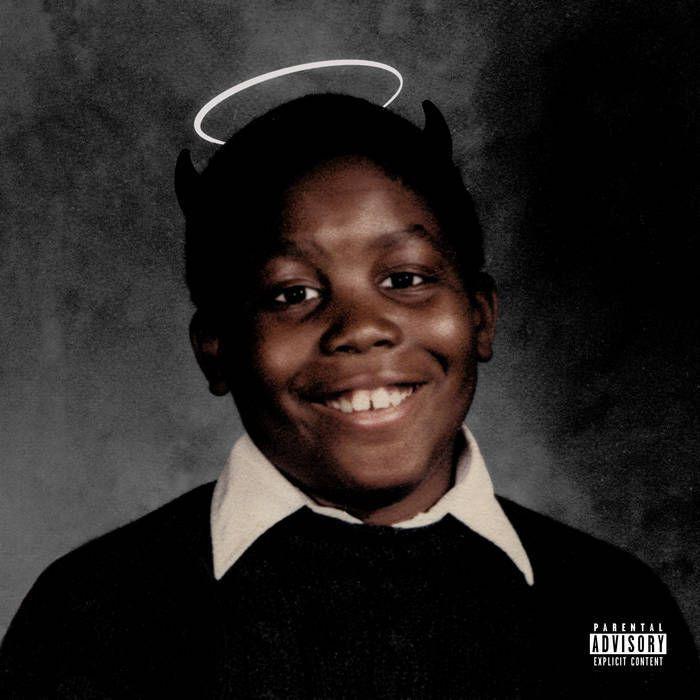

In this record, I was very sincere. I’d been walking the line for a long time. Early in my career, I was trying to manage: How do I be Michael and still be crunk? Then: How do I be Michael and still find a hit record? Run the Jewels gave me the freedom to just be a badass emcee and not have to chase a chart. We developed our own sound, our own brand. We’re one of the greatest touring bands, one of the greatest rap groups ever. Finally, Killer Mike is validated. And then I realized, sitting at home during the pandemic, that I’d never gotten a chance to introduce people to Michael. Now, I have an opportunity to show people the experience of a 9-year-old boy on that album cover with the halo and the horns, that little mischievous motherfucker who knows the word of God.

When we get off this phone, I’m going to take my shower, put on my clothes, get in my truck, and drive to my aunt’s house as my uncle transitions. My aunt is 88 years old; my uncle is 86. I’ve thought to myself: How strong do you have to be, as a woman, to watch your husband die? How strong do you have to be as a matriarch in a family where everybody still leans on you for advice and wisdom? I’m going to get up from this interview, and I’m going to go sit with my aunt, and we’re going to laugh, we’re going to cry, and we’re going to joke, because he was a philanderer and a taker, and I’m going to have a day in which I get and give energy. That’s what I wanted this album to be. I sent it to Jay-Z early, when it was still what I considered a mixtape. He hit me back and said, “I really liked it. It felt like all exclamation points. It felt like I got to go to my aunt’s house and watch a movie.” When you go to your aunt’s house, you might see a movie your mama might not let you see.

On the one hand, Michael is this distinctly Southern album, but that’s balanced against it also being very eclectic. The first other rapper you hear on this thing is Mozzy. The executive producer is No I.D. Let’s talk about that, actually. Why’d you go with No I.D. on this one?

That’s my brother. That’s my friend. That’s my musical Professor X. Dion was the Yoda to my Luke Skywalker. He’s the perfect music mentor. He challenges you to bring the best out of yourself. When the album was done, he said, “You haven’t cut deep enough. I need to know Michael. You are a superhero to people. Where are you weak? Where are you vulnerable? Where are you human?” I’m like, “I did shed tears. I talked about how hard it is to be a man.” He said, “No, no, you can go deeper.” I said, “The only thing I don’t really talk about that hurts me is my mother.”

That leads to him doing an original version of “Motherless,” him reconfiguring the beat right there in the studio, me going in and, for the first time in my life, saying, “My mother’s dead; my grandmother’s dead,” and I just start crying. Hannibal Buress, who’s a friend of mine, who’s an incredible comedian and a rapper, too—I didn’t realize he was a rapper first—brings in Eryn [Allen Kane], she starts singing, and it’s a wrap. I reached a level of depth that I had not reached before. You can be a great writer. You add some alcohol to it, you might fuck around and turn into Robert Frost or Mark Twain or Zora Neale Hurston. That’s what happened.

So it was essential for me to work with Dion. I had wanted to do it forever, and I’ll never be the same.

When I think of Killer Mike, rather than Michael, the song I think about most is “Reagan,” on R.A.P. Music. That song, to me, very perfectly represents what it means for a rap record to have a sort of adversarial engagement with politics and history. There are moments on this album when you talk about “that woke shit” and engage with the current political climate. Where are we in terms of hip-hop being a platform for provocateurs and people working out their frustrations with society?

I think that hip-hop does a great job. I think we’ve always done a great job. We are the only musical genre in which everybody, from Eminem to Future, from Boots Riley to Immortal Technique, has said something that pushed the line on politics on behalf of salt-of-the-earth, working-class, regular folks, the majority [of them] Black folks. Other genres and other artistic forms have talked about making a way for women. From day one, hip-hop has had a way for women. I don’t even feel like we’re talking about the Funky 4 + 1 or Roxanne Shanté, Salt-N-Pepa, Queen Latifah, and now there’s just an overabundance of dope-ass chicks. Rest in peace to my sister Lola, Gangsta Boo, who was one of the forerunners. So, hip-hop to me has done a great job of being what it’s called for the world to be. It’s not perfect, but goddamn, we’ve been great.

I am not just a political rapper. I think about politics and policy on a hyperlocal level because that’s what my grandmother poured into me. When Black club owners call me and say, “Mike, they’re proposing a city ordinance that would close our clubs and let corporate clubs take over,” I fly home on my off day, and me and 2 Chainz stand at the podium and tell city council why we disagree with their decision. That’s what my grandmother raised me to be. I was 5 years old at city council meetings at the hem of her skirt, hearing her complain about everything from sanitation to potholes, making sure that her community was represented. So in the name of Betty Clarks, that’s what I’m going to do.

I’m also apolitical in that I believe firmly in taking care of yourself and your neighbor. My grandfather was probably more libertarian in his views. He didn’t want the government involved, positively or negatively. My sister still grows her own food. I still fish. My friends have been trying to get me back out hunting. If everything falls apart, I know I can survive in the woods for three days.

I wanted to give people the whole of the 9-year-old boy that’s on the cover. That’s me for real. I was a good-intended, mischievous little motherfucker who loved rap music and whose grandmother forced him to go to church and be socially and politically active. You get to see this whole human being on Michael. Ultimately, I think that this album is going to connect with men of different cultures and regions and the women who love them. If you are a mother, a sister, a lover, a wife, a friend of a good man, you know that there’s a burden that gets carried. That man may have to sit in the bathroom, look in the mirror, and weep for a week to get it figured out, but he’s going to get it figured out. I think that energy deserved recognition.

I can remember playing “Slummer” [track no. 6 on Michael] for two guys and Outkast’s DJ, Cutmaster Swiff. One of them started crying profusely. The other had a few tears and said, “Man, I just have never heard a record that described what it felt like having to go through the abortion process as a man.” It hit everybody in that room, and all I was doing was telling my personal story of me and my first teenage love and how that ended up having to be an abortion, but her believing in me beyond being a dope boy and calling on me to do greater things.

There’s a bit on here where you shout out Three 6 Mafia and mention Gangsta Boo and Lord Infamous. Hip-hop is a culture that really forces you, as an artist or a fan, to engage with mortality. We lose a lot of rappers every year.

I was on the phone with a friend this morning talking about how in the height of the crack era in the projects, she would see the white insurance man coming through and mothers marching around with them, making sure the other mothers got life insurance on their sons. I can remember my grandmother and her sisters lining up us kids, who had learned how to write in cursive, [to sign] insurance papers for some of my uncles and cousins, because they were living such a tumultuous life. It was such a dangerous life that they just wanted to make sure they could bury their child. As I’m talking to you right now, when I leave, I’m going to go be with my family to watch my uncle transition so that my aunt isn’t alone.

Mortality is in Black gospel, it’s in blues, it’s in jazz—it is a part of Black music. Part of the inspiration for “Something for Junkies” is “Freddie’s Dead.” My mother left me that record when she moved out. Of all those records you hear about on Super Fly, “Freddie’s Dead” hit me, because it showed such empathy for someone who had become an addict, had been used and abused by the game.

In gospel music, there’s a recognition that this life will end, and hopefully, I go on to something greater. In hip-hop, there’s a recognition that this life is ending, so let me live today as best I can. There’s an understanding that death is going to come that, in the blues, comforts the hardest of men. I think that’s hip-hop’s job too.

I was listening to the latest Jack Harlow album, and he was working through some angst about hip-hop’s relationship with the suburbs. What do you make of that sort of angst? Hip-hop being in a lot of ways this distinctly Black working-class thing that represents a specific slice of the American experience but then also this thing that became for everybody after a point.

Well, at what point has Black music not done that? But hip-hop has learned a purposeful lesson in making sure it stays recognized that this is an extension of the Black experience. I can’t speak to the suburbs, because, shit, I’m in Atlanta. But we used to think hip-hop was only in New York when I was a kid. It was that young. I don’t approach hip-hop from a super urban experience, because I lived in a neighborhood 4 miles from the city. We had houses. But I think that hip-hop is, was, and always will be an extension of the Black experience.

With that said, no war is won without allies. In the South Bronx, beautiful Puerto Rican kids and beautiful artsy white kids helped take people like Fab 5 Freddy into the city for hip-hop to grow. Down in the South, you’ll find white boys from Southern Tennessee, North Georgia, South Georgia, North Florida that know 8Ball & MJG better than some people who grew up right in Memphis. I’ve not seen Black people shut out many people. We have provided a soundtrack for this country. That debt can never be repaid. Yes, it is something that’s distinctly Black. I want people who listen to Michael, who don’t look like me, to get an opportunity to be a voyeur of a Black Southern male and the people who love him.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.