When Gene Luen Yang started working on American Born Chinese in 2000, he had been making comics for only about five years. He would write and draw each issue, go to Kinko’s to make copies and staple them by hand, and then sell them to his friends or at local conventions in small numbers. In 2006, the series was published by First Second Books, and it became a New York Times bestseller, a winner of the Printz and Eisner Awards, and the first graphic novel to be a finalist for a National Book Award. Now, more than 16 years later, the graphic novel has evolved even further from its humble beginnings at Kinko’s into a big-budget TV series created by Kelvin Yu (Bob’s Burgers).

In its original form, American Born Chinese’s coming-of-age tale combines some of Yang’s real-life experience growing up in the Bay Area with fantastic elements of the Chinese classic Journey to the West. It consists of three distinct storylines whose themes eventually coalesce around racism, transformation, and self-acceptance. The first centers on the famed Monkey King of Journey to the West, who obsessively aspires to earn a place among the other gods in Heaven; the second focuses on Jin Wang, a Chinese American student who struggles to fit in among his mostly white classmates; and the third is styled as a satirical sitcom that follows a white high school student named Danny as his mischievous Chinese cousin seeks to ruin his reputation at school.

The graphic novel was groundbreaking in the way it broached the subject of racism with an audience of younger readers, and it helped kickstart an illustrious comics career for its author and illustrator, as Yang went on to work with industry titans like Dark Horse Comics, DC Comics, and Marvel Comics. Yet despite the book’s tremendous success, Yang didn’t expect his story to make it to the screen—let alone a screening at the White House hosted by President Biden. “There just didn’t seem to be that much interest in Asian American stories, or a story with an Asian American protagonist with a predominantly Asian and Asian American cast,” Yang tells The Ringer.

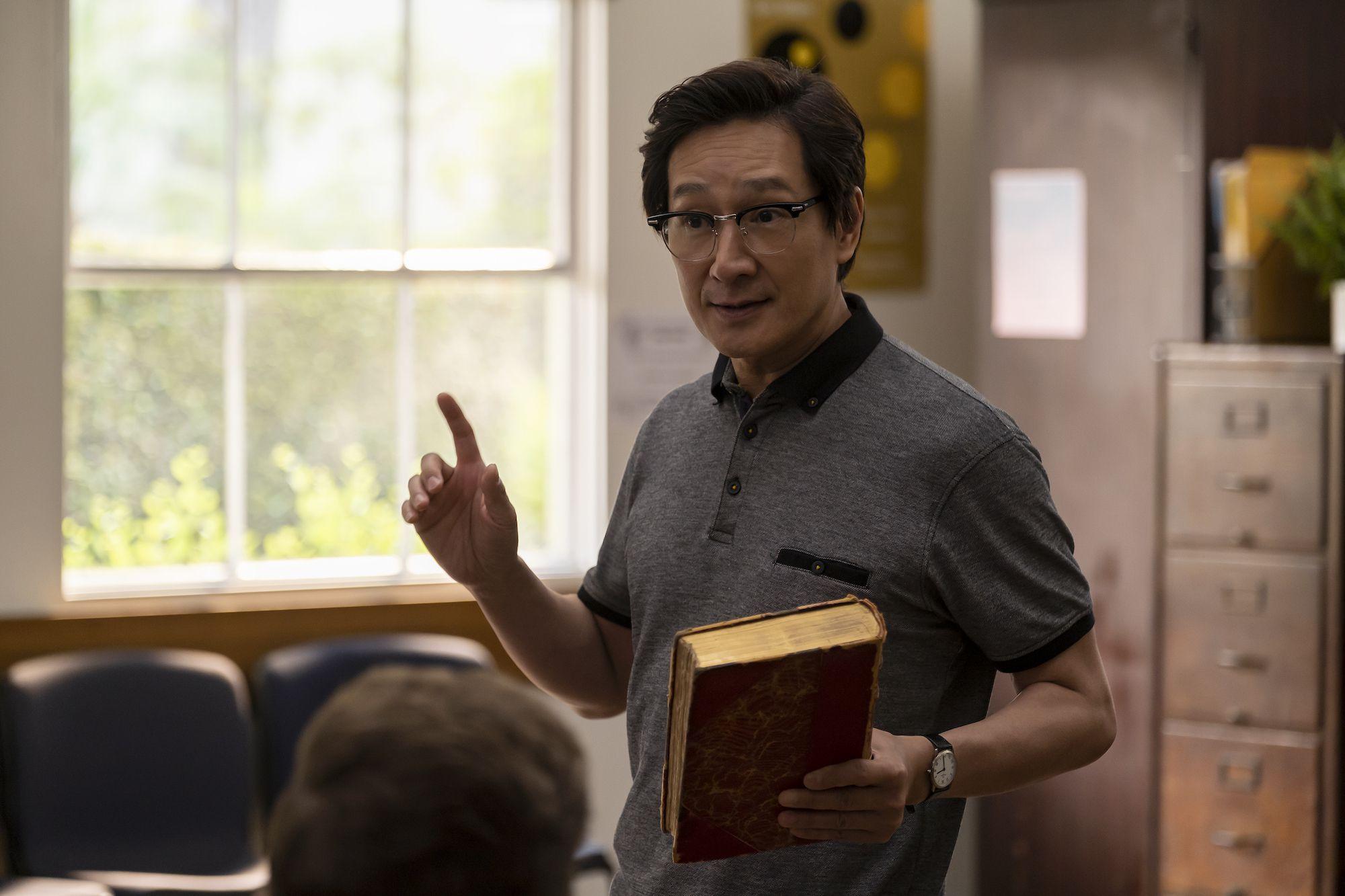

Although Yang serves as an executive producer on the series, which premiered on Disney+ on Wednesday, the project departs significantly from his original text, as Yu has led a new team of writers and artists in modernizing and expanding the story into a binge-worthy eight-episode season (all of which was released this week). The series streamlines the book’s three storylines into one, connecting them from the very beginning, with an increased focus on Jin’s (Ben Wang) experience navigating high school as his worlds collide with Wei-Chen (Jimmy Liu), the son of the Monkey King (Daniel Wu), who is trying to stop an uprising against Heaven’s Jade Emperor. And it also boasts an all-star cast of Asian and Asian American actors, which includes a reunion of many of the leading cast members of the Oscar-winning Everything Everywhere All At Once: Michelle Yeoh and Ke Huy Quan have recurring roles, while Stephanie Hsu and James Hong make guest appearances.

As American Born Chinese gets something of an MCU-style treatment to support its mainstream ambitions (with Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings director Destin Daniel Cretton even helming the pilot and the finale), the story dulls some of the comic’s finer edges to produce a Disney-fied experience. But it still manages to retain much of its soul as it transforms into an entertaining on-screen entity for all ages.

In some respects, such change was necessary as the story made its transition to a new medium. In addition to studios’ external resistance to adapting material like American Born Chinese in a time before ABC’s Fresh Off the Boat and 2018’s Crazy Rich Asians propelled Asian stories to greater prominence, there were also some personal concerns surrounding aspects of his source material—namely the aforementioned Chinese cousin character, Cousin Chin-Kee.

“Cousin Chin-Kee is the amalgamation of all of the negative Asian and Asian American stereotypes that have haunted me since I was a kid,” Yang explains. “And I was always a little bit freaked out about what would happen if that character ever made the leap from the page to the screen. I was worried that decontextualized clips of that character would show up on YouTube, and that would just be the exact opposite of what I was trying to do with the book.”

Cousin Chin-Kee plays a minor, yet crucial role in American Born Chinese. He stands as a deliberately offensive representation of all the racist stereotypes that have been aimed at Asians and Asian Americans in the media throughout the years, particularly during the vaguely ’80s/’90s era that the book is set in, along with the Yellow Peril stylings of anti-Chinese propaganda from the 19th century. (Speaking to The New York Times, Yang described putting Chin-Kee on paper as something of an “exorcism.”) When Cousin Chin-Kee first arrives on the page, he comes as a shock to his cousin Danny and the reader alike, as Yang’s cartoonish and playful art style is suddenly weaponized to eerie effect. In Yang’s hands, it was an effective storytelling tool, especially at the time the book arrived in the mid-2000s. But it’s also one that feels uniquely suited to the visual language of the comic book medium.

Yang credits Yu for quelling his concerns, as the showrunner—who cowrote the pilot with his brother Charles Yu (Interior Chinatown, Westworld)—came up with a couple of solutions for translating the character to TV. “One was, [Kelvin] took that fear that I had of decontextualized clips showing up on YouTube, and he makes it a plot point in the first episode,” Yang says. “Jin is confronted with these clips of himself, paired up with clips of the equivalent of the cousin character [Freddy Wong]. By doing that, Kelvin teaches the audience how to think about that character. The second thing he did was he filtered it through his own experience as an Asian-American actor.”

In addition to being a writer and producer, Yu is an actor who has decades of TV credits in mostly smaller roles, with one of the more prominent being a recurring role on Netflix’s Master of None. But his first credit came during a brief run as a character on Ryan Murphy’s Popular in 1999. “The whole point of his character was that he was comic relief,” Yang explains. “And the humor didn’t come from a personality quirk, it came from the fact that he was Asian. That character’s name is Freddy Gong, and Freddy Wong on American Born Chinese is in some ways a commentary on that first experience that he had as an actor.”

Throughout the season, Freddy Wong appears in self-contained scenes of the resurgent show-within-the-show, Beyond Repair. The ’90s-style family sitcom is gaining a second life on streaming services and has become a meme that perpetually torments Asian kids like Jin, as the stereotypical character serves as the butt to every joke. (His catchphrase: “What could go Wong?”) The story line doesn’t integrate with the main plot line revolving around Jin in a particularly natural or satisfying way, but Freddy and the sitcom revival is still a clever update, a plot point that feels current with the bonus of a portrayal by the Oscar-winning Quan. It’s a challenging role that Quan plays admirably, informed by his own experience of getting shut out by Hollywood after being a child star. The series eventually follows up with him years later—as the actor behind the sitcom star, Jamie—and explores the impact that the Freddy role has had on his life, adding a meta element to his character’s arc.

Between the haunting presence that Freddy becomes in Jin’s world, and the baked-in layers of Quan’s and Yu’s experiences as actors, the effect is similar to Cousin Chin-Kee’s in the graphic novel, despite the new character’s more amalgamated origins. “Early on I realized the comic is a ‘me’ story, but this television show is going to be an ‘us’ story,” Yang says. “It’s going to be a bunch of different people putting pieces of themselves into this common project. Kelvin definitely put pieces of himself in, but even the set designers, the costume designers, the directors, they all did.”

Yang continues, “The differences between the book and the show do highlight the differences between these two storytelling mediums. My hope is that they have a conversation with each other. That if you read the book and then watch the show, the differences between the two will say something. They’ll say something about the difference between the media, what you can do in a graphic novel and what you can do in a television show. But I also hope they’ll say something about us as Asian Americans.”

Aside from the major overhaul Freddy represents, American Born Chinese expands on its source material in myriad ways that better fit the series’ 2020 setting. Jin’s Asian-American classmates try to rally in support of him after he’s the victim of a bullying incident, much to his horror and embarrassment. There is an increased focus on Jin’s parents, Simon (Chin Han) and Christine (Yann Yann Yeo), whose marital issues, personal struggles, and generational divide with their son ground the family drama that serves as one of the main tensions in Jin’s very eventful high school life.

But perhaps the most significant of the show’s changes is the way its story’s main conflict stems not from Jin’s life on Earth, but from Wei-Chen’s mission to prove himself to his father Wukong (the Monkey King) as he tries to prevent the Bull Demon’s uprising in Heaven by finding the fabled Fourth Scroll. “The expansion of the Chinese mythological world in the show was a result of a decision that we made early on to adapt the graphic novel not as a movie—which has a finite beginning, middle, and end—but as an open-ended television series,” Yang explains. “For an open-ended television series, you have to have a world that is rich enough to hold a bunch of different stories. That’s when Kelvin and his writing team started folding in these other characters that I didn’t have in the book, that are a part of Journey to the West.”

A significant byproduct of the show’s bid for longevity is an increased focus on action: Each episode features at least one major fight sequence. The CGI may falter at times, just as it does in other Disney+ content that depends on the overstretched VFX industry, but the show’s practical effects and impressive fight choreography more than make up for the flaws. Peng Zhang serves as the stunt coordinator (in addition to directing the fourth episode), and he deftly incorporates some wuxia- and Hong Kong action-style influences to enliven the show’s combat. (Zhang also worked as a fight coordinator on Shang-Chi, which shares similar influences.) There are some truly fun fight scenes in the series, including one that features Yeoh’s Guanyin, the goddess of compassion, and another that uses Ronny Chieng’s Ji Gong in a Drunken Master-style tribute.

American Born Chinese has a lot going for it—but perhaps too many moving parts for it to add greater depth to its abundance of characters, or to avoid a surfeit of familiar coming-of-age tropes. Some time devoted to peripheral characters could be better spent on the standout performances by its young leads, Ben Wang and Jimmy Liu. And some of the original story’s more thorough examinations of identity and race are oversimplified on TV; the Disney+ series often portrays characters’ acts of racism as products of sheer ignorance, as opposed to the more pronounced and realistic forms of bigotry shown in the book (and observed in real life).

The show may not be a direct sequel to Yang’s graphic novel, or even a story that he can call solely his own anymore. But though it may have had to sacrifice some of what made its source material so singular, it’s now possible for a version of American Born Chinese to reach an even larger audience, and a new generation.

“I thought the one book was the end of that story,” Yang says. “I’ve been asked in the past if I was going to do a sequel graphic novel, and that’s never really interested me. I just felt like I said what I wanted to say in that world, and I was OK with that. But this is an adjacent adaptation, and to see how this entire team of creatives has built this new world that is based on the world of the book has been amazing.”

American Born Chinese has taken on a life of its own, and with a finale that teases the potential of more seasons to come, its story may be far from over.