The NFL’s version of the Final Four is officially set, and it certainly feels as if it’s made up of the league’s four best teams. The Bengals and Chiefs will meet for a fourth time in two years, with Cincinnati looking to win its fourth consecutive game against Kansas City. And the Philadelphia Eagles and San Francisco 49ers will duke it out for the NFC title after both thoroughly dominated the conference this season. Since November, this group of four has lost a combined total of four games—and only three if you don’t count the Chiefs’ Week 13 loss to the Bengals. It’s hardly a surprise that they’re the last ones standing.

NFL seasons are often defined by the teams that dominate them, and 2022 was no different. The Bengals, Chiefs, 49ers, and Eagles weren’t just the best teams this season; they were also among the most fascinating to track for a variety of reasons. There’s a lot to learn from how these teams were built, how they played, and how they approached each and every game. So as the season winds down to its conclusion—a sad reminder that we have only two football Sundays left before the dreaded offseason—let’s take a look at the biggest lesson we can take from each of the franchises left competing for a spot in Super Bowl LVII.

The Bengals taught us … that the best defense is an adaptable one.

Modern problems require modern solutions. In today’s NFL, in which we’re seeing an increasingly diverse array of offensive systems, it’s becoming more and more difficult to get by without a defensive coordinator who’s willing to adapt to the opponent. Offenses just have too many buttons to press for defenses to sit in the same personnel groups and the same defensive fronts and coverages and expect to survive a full 17-game season plus playoffs. They will eventually run into a bad matchup and get exploited. The scheme that works against, say, Miami’s RPO-heavy, shotgun-based offense may not do so well against Detroit’s under-center run game and play-action pass attack. What works against Patrick Mahomes may not work against Joe Burrow. You get the idea.

More than ever, defenses have to be able to shape-shift, and there’s not a coordinator better at doing that than Lou Anarumo—as evidenced by Cincinnati’s 27-10 win over the favored Bills on Sunday. The Bengals defense disguised its coverages on almost every play. They sent blitzers from unorthodox places and angles. The same coverage was rarely called twice on the same drive.

Anarumo was throwing gas all afternoon, and as a result, Josh Allen never got comfortable. According to TruMedia, Allen was pressured on 44.7 percent of his dropbacks and was inaccurate on 14.3 percent of his passes. It was one of Allen’s worst games of the season. But the fourth-year pro isn’t the first top quarterback to have been duped by Anarumo, and he won’t be the last. The coordinator’s bespoke game plans have taken down some of the best at the position.

There are, of course, exceptions to the shape-shifting rule. Defenses loaded with talent have historically been able to just line up and play without really worrying about how the offense will attack them. When you’re the better unit, there’s no need for trickery. The Eagles have proved that this season. They have a secondary full of Pro Bowl talent and a defensive line that’s as deep as it is skilled. Coordinator Jonathan Gannon doesn’t need to reinvent the wheel every week when his players can just take the wheel and bludgeon opposing offenses with it until they give up. Even then, though, you’ll eventually run into an offense that can match your talent, and that’s when ingenuity is required—or else you risk going out like the team whose season was ended by the Bengals on Sunday.

The Chiefs taught us … that you don’t need to throw downfield to be explosive.

Think about how much time we wasted wondering how Tyreek Hill’s departure from Kansas City was going to affect Mahomes. Even without the NFL’s fastest receiver, the Chiefs finished atop the NFL in just about every major metric this season, including offensive DVOA, expected points added, success rate, and points scored. Mahomes is also a few weeks away from adding a second MVP award to his résumé. Yes, Kansas City’s offense could probably be even better with Hill burning defenses deep, but the trade provided much-needed cap relief and draft capital the Chiefs can use to build up the rest of the roster.

The temptation to launch the ball to Hill at every opportunity probably had something to do with the issues Mahomes faced last season, when seemingly every opposing defense majored in two-high coverages and tried to take away the deep areas of the field. At times Mahomes looked uncomfortable with or straight-up uninterested in taking what the defense gave him, and it eventually led to his team’s demise in the AFC title game. In that game, Anarumo forced Mahomes to be a patient pocket passer who was either throwing into a tight window in the intermediate area or checking it down and hoping to keep the offense on schedule. Mahomes got a bit too aggressive—and Andy Reid seemingly forgot he was allowed to call a run play—and the opportunistic Bengals defense capitalized on those mistakes.

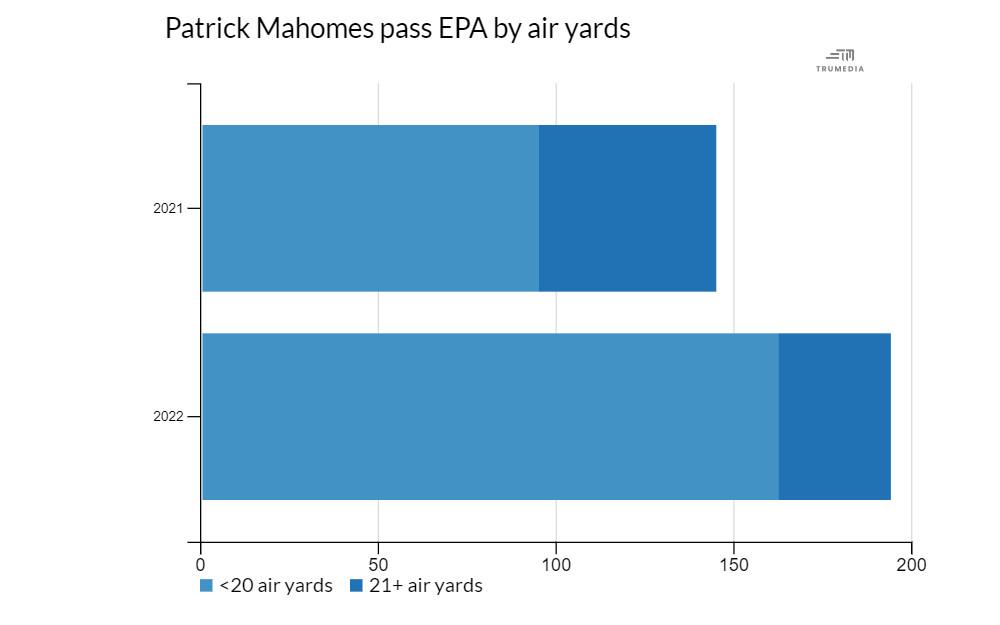

That loss must have stuck with Mahomes all offseason, because we saw a new version of the QB emerge in 2022. This Mahomes is still fully capable of making the most absurd play you’ve ever seen—how about a jump pass from the tightest of pockets?—but now he rarely makes mistakes on the downs in between. Mahomes isn’t just throwing more checkdowns; he’s throwing more short passes in general. He’s processing and getting rid of the ball faster, and he has replaced a lot of those downfield heaves to Hill with more sensible passes to Travis Kelce, JuJu Smith-Schuster, Marquez Valdes-Scantling, and Kadarius Toney. And none of that has affected Mahomes’s stat line in the slightest. He’s still producing at the highest of levels—he’s just finding that production in other areas of the field.

Mahomes isn’t the only quarterback who’s made that adjustment this season—defenses across the league are playing more two-high coverages and softer zone defenses, forcing passers to throw more underneath. Burrow has had to change: After he tore up the league with deep perimeter passes to Ja’Marr Chase and Tee Higgins in 2021, Burrow’s average depth of target has dropped by nearly a full yard (7.7 to 6.8) this season. Justin Herbert and Tom Brady both saw their aDOTs drop this year, too, and while there were some personnel- or coaching-based issues contributing to that, the league-wide aDOT also fell between 2021 and 2022.

Mahomes was seeing those coverages two seasons ago, so he was already ahead of the curve. But we’ll see how much progress Mahomes has truly made on that front when he gets another shot at Anarumo’s defense on Sunday. The Bengals coordinator will likely employ a plan similar to the one he used to frustrate Mahomes last January. And this time, he won’t have to worry too much about the quarterback escaping the pocket after the Chiefs star suffered a high ankle sprain in the team’s win over Jacksonville on Saturday.

The 49ers taught us … that the best offenses live in the middle of the field.

This is Kyle Shanahan’s masterpiece. And that’s saying something about a coach who has led some of the best offenses we’ve ever seen.

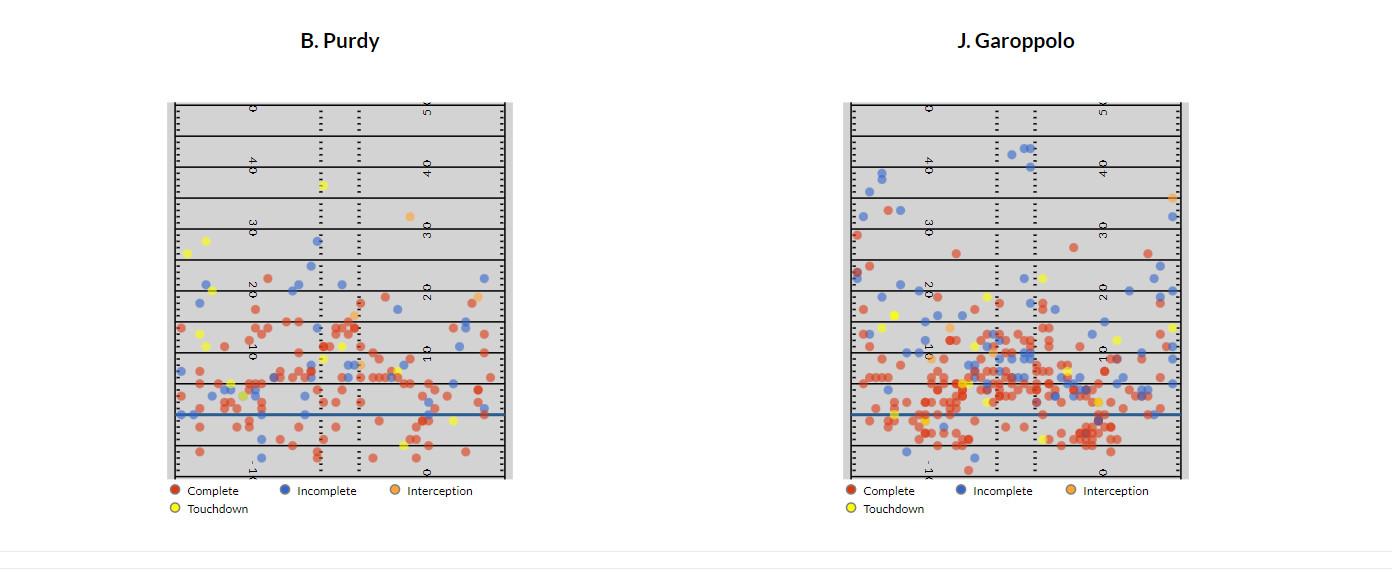

Taking a team forced to start a seventh-round pick at quarterback to within a game of the Super Bowl should be considered Shanahan’s greatest accomplishment to date. And it’s not like Brock Purdy has come in and sparked the passing game in ways that Jimmy Garoppolo could not. He is doing a bit more out of structure, sure, but his passing maps are largely similar to the ones Jimmy was producing before his injury. Here are their respective 2022 heat maps, via TruMedia:

Like Garoppolo before him—and really any 49ers quarterback who has enjoyed success in Shanahan’s QB-friendly scheme—Purdy is living on a steady diet of throws to receivers running in-breaking routes to the middle of the field.

Shanahan’s ability to create throwing windows is the key to this offensive machine. He does that in various ways, using presnap motion, formations, and play-action fakes. And he does it because throws to the middle of the field are the easiest ones for a quarterback to make. That’s why so many of the best defensive coaches in the league fixate on clogging up the middle and forcing quarterbacks to look outside. Unsurprisingly, the league’s accuracy rates fall from 92 percent on throws aimed inside the numbers to 84 percent on throws to the perimeter, according to TruMedia.

The 49ers defense, which carried the team past the Cowboys on Sunday in a 19-12 win, is also based around that idea. No other team is better at taking away the middle of the field than DeMeco Ryans’s bunch. Having Fred Warner doing otherworldly shit like this on a weekly basis has certainly helped …

… but even an alien like Warner needs help covering that ground. He gets it from Ryans’s scheme, the pass rush, and teammates who share his passion for swarming to the football and punishing ballcarriers who have the audacity to try to gain extra yards after the catch.

The 49ers have owned the middle of the field on both sides of the ball. If they can keep it up for two more games, they could be the owners of a record-tying sixth Lombardi Trophy.

The Eagles taught us … the value of playing 11-on-11 in the run game.

This one is just basic math. For years, before the NFL started to embrace the option concepts that had been dominating at the college level, offenses always played a man down in the run game. There were still 11 guys out there, but the quarterback wasn’t doing anything other than handing the ball off and getting out of the way. Then, when the zone read fully infiltrated the league around 2012, thanks to dual-threat quarterbacks like Cam Newton and Robert Griffin III, the math changed for teams that were willing to embrace it. Here’s Shanahan explaining why it’s such a useful concept for offenses—and such a pain for defenses.

“[For defenses], it’s how do you want to attack it?” Shanahan said in 2018. “What do you want to do off it when they 100 percent commit to stop it? Which you can, but that opens up everything else, so what do you do to scare them out of everything else? Is your quarterback good enough at running with the football to make them commit to stop it? And once they do, is he good enough to make the passes that he has to, that they just opened up? And if he is, that’s a huge issue.”

We can safely say that the Eagles have found one of those guys. Jalen Hurts has been a talented runner since his days leading Alabama’s offense, and Philadelphia has put that skill set to good use since he became the team’s starter at the end of the 2020 season. Now there are obvious benefits to that in the run game—option runs outperform traditional run concepts every season—but the more significant benefit is the space that rushing threat opens up in the passing game. There has been so much talk about the increase in two-deep safety coverages and the effect that’s had on the league’s passing numbers, but in order to keep two safeties deep, you have to play light in the run box. That is much, much harder to do when the quarterback can take off with the football.

To account for the extra potential ballcarrier, teams have to drop a safety in the box and play those one-high coverages that offenses love to see. These option threats create passer-friendly environments, which makes things easier for the offensive coordinator calling the plays and the receivers who don’t have to worry about an extra safety playing over the top. The Giants cobbled together a functional offense based around Daniel Jones’s athleticism. Bears quarterback Justin Fields looked like a surefire bust until Chicago finally started using him on designed carries. The Saints have won multiple football games with Taysom Hill starting at quarterback and he couldn’t complete 60 percent of his passes as a fifth-year senior at BYU!

After embarrassing the Giants on Saturday night, largely using these option run concepts, the Eagles are one game away from a trip to the Super Bowl—and Hurts is two games away from tearing down the silly notion that you can’t win a title with a running quarterback.