If there’s a theme to this MLB offseason, it’s superstars signing contracts that run through years so far in the future that they sound like science fiction. Prior to this winter, only one free agent, Bryce Harper in March 2019, had garnered a more-than-decade-long commitment. That total has quadrupled in the past few weeks, as Trea Turner and Xander Bogaerts inked 11-year contracts with the Phillies and Padres, respectively, and Carlos Correa came to terms on two different extended-duration deals; the first, a 13-year pact with the Giants, was scrapped and replaced by a 12-year agreement with the Mets. Turner and Bogaerts are now under contract through their age-40 seasons, while Correa’s slightly reduced term would take him through his age-39 season. If you were born before those players, I don’t recommend doing the math on how old you’ll be when their deals are done.

Fairly long-term engagements weren’t solely reserved for the market’s trio of marquee shortstops. Aaron Judge, who’ll turn 31 in April, signed a nine-year deal. Brandon Nimmo got eight years, Dansby Swanson got seven, and Carlos Rodón got six. Even Andrew Benintendi procured a five-year deal, as did Willson Contreras and Kodai Senga.

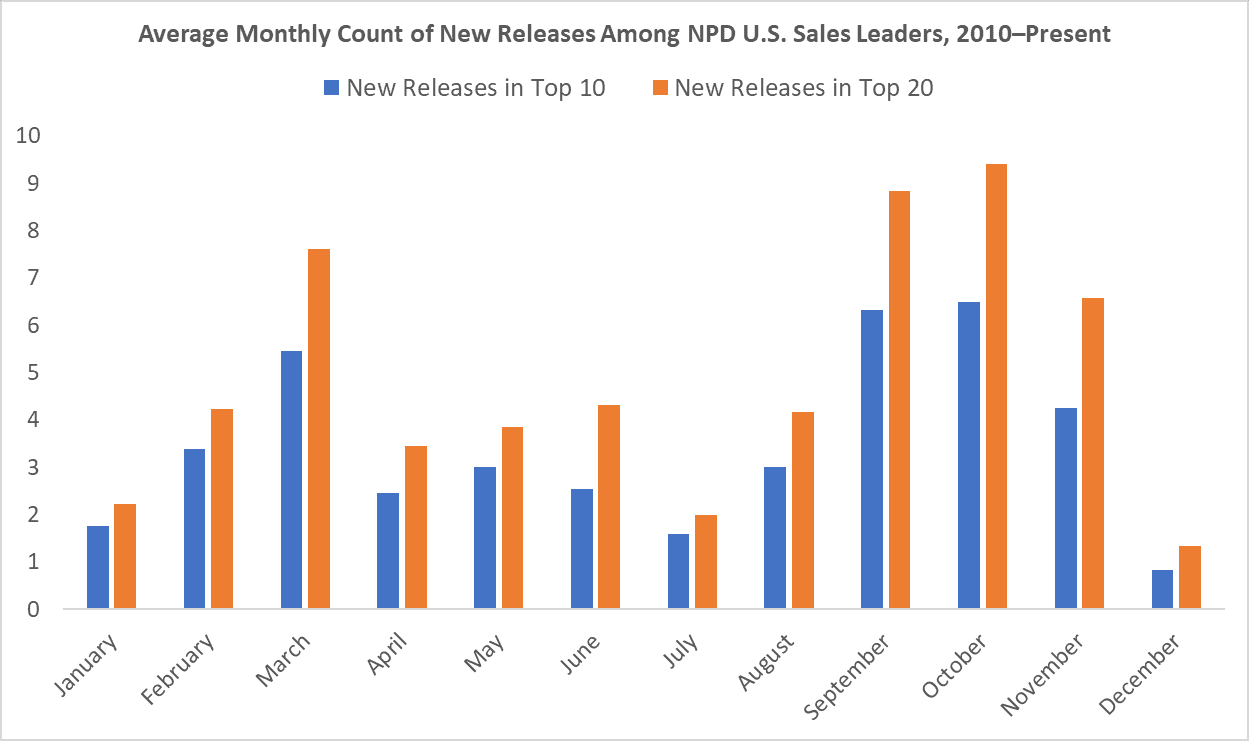

Swanson, who committed to the Cubs on Saturday, was the last to sign of the top 20 free agents as ranked by MLB Trade Rumors, which allows us to make some clean comparisons. MLBTR founder Tim Dierkes started ranking free agents in the offseason of 2005-06, which gives us an 18-year sample with which to assess this winter’s activity. And as one would suspect, this year’s contracts for the most desirable free agents are extraordinarily long. The graph below shows the average lengths of the contracts secured in each offseason by the top 10 and top 20 free agents.

Those are significant spikes. In the past 17 offseasons, the average term of contracts signed by top 20 free agents was 3.3 years. This offseason, it’s 5.5 years, an increase of roughly 63 percent over the established baseline. The uptick is even more notable for the top 10, whose deals average 7.6 years in length, an approximately 78 percent hike over the historical norm of 4.3 years. It’s not the annual salaries that have surprised people (though they are higher than ever): This winter’s top 10 and top 20 free agents have commanded $27.8 million and $24.3 million per year, respectively, below MLBTR’s predicted rates of $30.8 million and $24.8 million. But the number of years per agreement has topped MLBTR’s forecasts by 0.7 years, on average, for the top 20 free agents and 1.8 years for the top 10. Eight of the top 10 got longer deals than anticipated, and only one of the top 10 (Justin Verlander) and four of the top 20 got shorter deals than anticipated.

On the surface, this all seems somewhat curious, considering some countervailing trends. As Scott Miller observed in The New York Times, the results of the 24 contracts to date that have run 10 years or more don’t argue overwhelmingly in favor of issuing additional decade-long deals. Miller notes that “no free agent signed to such a deal has remained with his team for the entire term of the contract,” and only one extra-long-extension recipient (Derek Jeter) has gone the distance with one team. (Granted, a good number of those contracts are still active.) Nor are modern players better bets to age well, despite improved coaching, training, and nutrition (which benefit younger players, too). Just the opposite, in fact: In 2020, analyst Jeff Zimmerman found that relative to earlier eras, “hitters seem to be aging faster, especially after their age-30 season.” We’re not far removed from winters when “Don’t trust anyone over 30” seemed to be general managers’ motto, which was blamed, in part, for a series of stagnant markets. Yet teams are suddenly lining up to sign players well into their sports senescence. What gives?

As one might imagine, teams have their reasons, including the following five:

1. Happy Days Are Here Again

Even in 2020, it wasn’t truly bad business to be an MLB owner, despite what some of them claimed. But in the first “normal” offseason since 2019, one well past the peak of the pandemic and with a new labor agreement in place, baseball’s economic boom times are back. During the 2022 regular season, attendance bounced back to 94 percent of 2019 levels, compared to 66 percent in 2021 and zero percent in 2020, when players performed in front of empty stands or cardboard cutouts. Sponsorship deals are raking in cash (with patches on jerseys expected to send sponsorship bucks soaring higher in 2023), the proceeds from broadcast and streaming rights keep climbing, and each owner just received a $30 million payout from the completion of Disney’s purchase of MLB’s streaming-technology spinoff. All in all, revenue has recovered to near record levels, not even counting the capital derived from sources that the league considers non-baseball-related, like land developments and the Disney deal.

Last offseason’s flurry of spending in November brought more modest increases in contract length, but those deals went down amid fears of a work stoppage that threatened to endanger the 2022 season. With no lockout looming this winter, short-term CBA certainty secured, and more clubs in contention because of the 12-team playoff field, teams feel more secure in spending. And with the latest round of labor battles behind them, owners have less immediate motivation to complain about “biblical” losses and performatively empty their pockets and pull them inside out, like the subjects in stock photos of broke businessmen. Basically, conditions were ripe for teams to splurge, and sure enough, that’s what we’ve seen.

Some team sources have complained about disparities in resources—one anonymous executive whined to The Athletic’s Jayson Stark about “irrational people operating in an illogical market,” and another lamented to Stark’s colleague Evan Drellich that the Mets show “no care whatsoever for the long term of any of these contracts, in terms of the risk associated with any of them.” But even though not every club has a bottomless bankroll, the other billionaires live in massive mansions, too. Most, if not all of the clubs spending less on their whole payrolls than the Mets will on competitive-balance taxes alone could afford to increase spending and pursue superstars themselves.

2. ABC, CBT, AAV, Baby You and Me

You’ll be shocked to learn that in leagues with salary caps, teams have sometimes been known to employ creative accounting in an effort to buy themselves more payroll room. Hence NFL free agency’s “voidable years,” or maybe most notoriously, the NHL’s Ilya Kovalchuk contract, in which the New Jersey Devils tried to sign Kovalchuk to a 17-year contract that would have paid him $98.5 million for the first 11 years and then $550,000 in each of the last several seasons, right up until the winger was 44. The league struck down the deal, a transparent attempt to game the cap system—which went by average annual value—by tacking on seasons in which Kovalchuk wouldn’t make much money and wasn’t actually expected to play.

Much to Mets owner Steve Cohen’s delight, MLB doesn’t have a hard cap, but it does have a soft one in the form of the competitive balance tax, which also essentially works by adding up the average annual values of players under contract. By making those contracts longer, teams can satisfy players’ dollar demands while lowering AAVs, thereby giving themselves more room to add players without triggering payroll penalties. Given the incentives at play, it wouldn’t be surprising to see MLB teams keep pushing the envelope until someone tries to enter the Kovalchuk zone.

The thought has crossed clubs’ minds. The Phillies reportedly contemplated offering Harper a 20-year deal in 2019 before offering him first 15 years and then 13. And the New York Post’s Jon Heyman reported this month that before the Yankees re-signed Judge, the Padres “were contemplating a deal for $400 million-plus over 14 years that would have taken Judge to 44 years old,” but that “they would not have been allowed, as MLB would have seen the additional years as only an attempt to lower their official payroll to lessen the tax.” However, other media members cast doubt on the notion that MLB had nixed the Padres’ idea: The Athletic’s Ken Rosenthal wrote that “the Padres never made Judge such a proposal, so the league had nothing to consider,” while league sources cited by ESPN’s Buster Olney disputed that MLB “would have rejected one of the contractual structures the Padres had discussed.”

The CBA says that teams and clubs can’t enter into agreements “designed to defeat or circumvent the intention” of the competitive balance tax, which they’re arguably already doing. But the long-term deals we’ve seen so far haven’t extended far enough or mandated AAVs low enough to test the tolerance of the league—which doesn’t mean we won’t get there.

The impetus to skirt the CBT has existed since the tax was implemented 25 years ago, but the penalties have gradually gotten stiffer, even coming to incorporate potential draft-pick costs. As Joe Sheehan wrote recently, “Teams now have the strongest incentives in a long time to minimize AAV. There was a time they did so to keep short-term expenditures down, a time before massive national and local television deals made next year’s cash flow a non-issue. Now, they want to keep AAV down as a means of keeping the payroll from interfering with their ability to operate in the amateur talent markets.” Voila: long contracts that rank near the top of the total-dollar leaderboard without coming close to setting AAV high scores. And even as we see some players, young and old, opt for very short-term, high-dollar deals, others are choosing the opposite extreme.

It seems sort of ironic that owners would have fought so hard to hold the line on CBT thresholds in the recent CBA negotiations, only for some teams to turn around right after that and look for ways around the moderately lifted limits. Really, though, it’s a classic collective action problem: Even if owners as a group would benefit by keeping costs down, individual owners have good reason to avoid the system’s constraints. Heyman reported that Cohen was “OK with” implementing a fourth CBT—the so-called “Steve Cohen tax”—if MLB thought it was “for the greater good.” (The “good,” from the owners’ perspective, being both promoting competitive balance and suppressing salaries.) But he may already have been planning to blow everyone away in spite of those restraints.

3. Can I Interest You in Interest Rates?

Probably not! But that doesn’t mean they don’t matter. The CBT has gotten harsher, but it’s not new. What is new—or, at least, unseen for some time—is the prevailing economic climate. As FanGraphs writer and business-understander Ben Clemens has pointed out, interest rates, like inflation, are very high right now, which affects the time value of money. Rather than pretend that I, like Clemens, am a former interest-rate trader, I’ll let him explain, using the terms of Correa’s since-scuttled pact with the Giants:

At an interest rate of 3.61%, the Giants would have to put away $285.4 million today to secure Correa’s payments for the next 13 years. By the time they’re paying for the last year of the deal, they’d only need to invest $17.59 million today; compounding interest is a powerful force. But lower interest rates change the equation meaningfully. At 2021’s prevailing rates, they’d need to invest $320.9 million to fund a 13-year, $350 million commitment. At 2020’s rates, they’d need to invest $331.8 million. The cost of Correa’s contract, at least in present value dollars, has declined significantly thanks to rising interest rates. If you’re a team discounting everything to present value, the Correa deal looks $50 million smaller than it would have under 2020 interest rates. That’s a massive difference.

As Clemens sums up, “Higher interest rates? Push your liabilities further into the future, even if it means paying a higher total amount of dollars. Lower interest rates? Future liabilities hurt more, so keep contracts short.” Teams seem to be sticking to that script.

4. These Guys Are Good

Even now, teams aren’t handing out really long contracts to just anyone who wants one; average players aren’t getting 10-year deals. Consummating those contracts is contingent on finding the right recipients. Thus, the deals distributed this offseason are partly a testament to the quality of this class of free agents; as Sheehan wrote, “I think the players available this winter, and you can fold recent contracts for Bryce Harper, Manny Machado, and Corey Seager in here as well, are the biggest factor.” The players who’ve landed the longest deals are generally under 30, play premium positions, and possess skill sets that make it seem semi-plausible that they could still have something left in the tank in 10 years—and this winter, there were plenty of players like that to be had. In terms of age, build, and natural position, Judge is the exception, but he’s an exception in more than one way. If you hit the market following one of the most impressive seasons ever, you’re going to get paid, even if you’re old enough to predate the Rockies and the Marlins.

5. The Buck Stops Somewhere Else

Sometimes I stay up too late because I’ve persuaded myself that the fatigue I’ll feel the next day is my morning self’s problem. Why should my night self suffer? It’s not a smart strategy, because my morning and night selves are the same person, and the sleep-deficit sins of the previous night are visited on the next morning.

MLB teams’ decision-makers, though, can kind of punt the downside of decisions to someone else. Most heads of baseball operations departments will roll (or willingly relocate) before the longest-term contracts expire, and team owners tend not to be a youthful bunch. By the time today’s late-20s shortstop turns 40, he’ll quite likely be some other GM’s (or even owner’s) financial burden to bear. If guaranteeing an 11th or 12th year you won’t be around to see helps you win a World Series and burnish your legacy in the short-to-medium term, why worry overmuch about what will happen when the subsequent bills come due? You think 66-year-old Phillies president of baseball ops Dave Dombrowski is sweating Turner’s 2033? Sure, he’s charged with doing what’s best for the franchise, but spending some of John Middleton’s money on an MVP-type talent is undoubtedly good for the Phillies today. The long-term consequences are some unspecified successor’s problem. YOLO! Moral hazard is a hell of a drug.

Plus, today’s teams grasp the concept of sunk cost and realize that they don’t have to roster and start an unproductive player who still has a high salary. Just because you’re paying a faded 40-year-old star at the tail end of a long-term deal doesn’t mean you also have to play him and incur an on-field, competitive cost in addition to the financial one. There’s always the option to release him, as the Angels eventually did with Albert Pujols, or pay him to retire, as the Orioles did with Chris Davis. The checks or direct deposits keep coming either way, but without the in-game reminders that a former franchise player isn’t what he once was, it’s easier for fans to fondly remember the sowing while the reaping plays out off screen.