Change Is Coming for Everyone in College Football—Even Alabama

For just the second time since the College Football Playoff began, Alabama will be on the outside looking in. This doesn’t mean the Crimson Tide’s reign is over, though—just that they’re the sport’s bellwether in a new way.

The most important part of following college football is bullshitting yourself. If you cannot lie to yourself, you cannot watch the sport for more than 10 minutes. That linebacker who couldn’t cover tight ends last year? He looks great in spring practices; problem solved. The transfer left tackle? He’ll plug a hole; nevermind why he couldn’t find playing time at Arizona. The coach who left us? Secretly miserable in his new spot. Plus, he was a bad gameday coach. The rival that won five more games than us? They are about to crash and burn. Everyone knows it. And the recruit we lost to that rival? Our coaches cooled on him. Not a take. Sort of feel bad for the school that did take him.

See? It’s easy.

College football is the cruelest sport because of this. Former MLB commissioner Bart Giamatti once said his sport was “designed to break your heart,” because it leaves you just before it gets cold outside and you want it around the most. But really, that’s college football. The season, played across three months, acts as a very quick undoing of all the lies you told yourself. The linebacker still can’t play. The left tackle got benched. The coach who left you is 8-0. That recruit looks awesome in limited snaps. Unlike other sports that legislate fairness—an NFL team can get a no. 1 pick who instantly changes the franchise; a baseball team owner can start spending more money; an NBA superstar might develop in front of your eyes and stay for a decade—your fortunes aren’t changing that much in college football. And because it has the shortest season of any major sport, you’re left with eight months to stew and recycle the same lies from the year before.

College football is about recruiting bases, resources, and coaching—with the last part dictated by the first two—and there’s not a ton of variance from year to year in those things. You usually are what you are; and sometimes that means doing everything as well as you possibly can for a given program and getting laughed out of a stadium on Saturday anyway. No sport has more referendums on where you are. You always know.

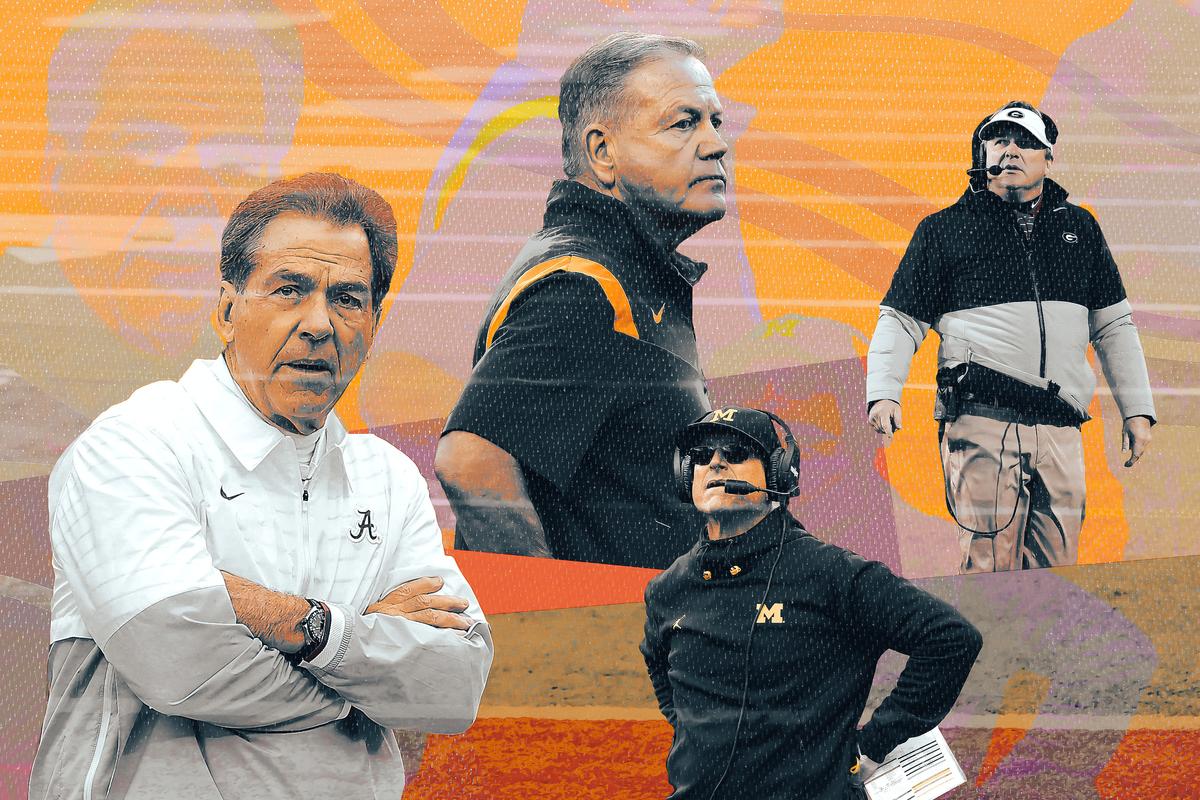

Alabama has served a ruthless purpose since Nick Saban’s first national title 13 years ago: to tell other programs that they are not the team they think they are. They are not reaching the mountaintop. Go back to the message board and cope there. In most seasons, Alabama is the grim reaper for all of our delusions, proving that even in a sport where it feels like anything can happen on any given Saturday, there are very few actual miracles over the course of a season. There are only five active head coaches who’ve won a national title—only three of them are still at the school where they won it (Saban, Kirby Smart, and Dabo Swinney). There is a metric called the Blue Chip Ratio that says in order to compete for the national title, a team must sign more five- and four-star recruits than two- and three-star recruits. The threshold to win big in college football has been higher than any other sport for its entire existence. There are no mysteries. This is the landscape Alabama has ruled—one where everyone knew how to be good, and no one was nearly as good at doing so as Saban.

But on Sunday, Alabama missed its second College Football Playoff ever. Georgia—the biggest current threat to Alabama’s long-term supremacy—Michigan, TCU and Ohio State will play later this month for the chance to reach the national championship game. A two-loss Alabama was kept out of the field—and yet that tells as much of a story about college football this year as it does when they make the playoff.

It’s been over a decade since Saban, addressing Alabama fans after his first national title there, said, “This is not the end, this is the beginning.” He was exactly right, and in the ensuing years, fans of every other program in the nation have been begging for that end to come. Instead, Saban’s won six national titles in 12 years and has made seven playoff appearances since the format’s introduction in 2014. Even with their miss this year, Alabama’s end is not coming. The Crimson Tide has the no. 1 recruiting class in the country for 2023, and its previous top-ranked recruiting class, from 2021, will be entering its third year next season. Which means Alabama is still stacked. It currently has the most talented roster in college football, according to 247’s Talent Composite metric, and this will not appreciably drop next year even when star quarterback Bryce Young and star linebacker Will Anderson Jr. head to the NFL. I would not be surprised if they win the 2023 national title, because that is just what they do.

What will be different about college football going forward is not Alabama fading. That will not happen. It’s that there are more mechanisms now—namely the year-old transfer portal rule in which a player can change teams and play immediately, and the ability to quickly assemble a veteran roster using NIL cash—that will make it easier to reach the top of the sport quicker. We will see those mechanisms put to use as much as we ever have in the next few weeks, and next year we will see a season defined by them. Add in the 12-team playoff launching in 2024 and you won’t see parity, exactly—that will never exist in college football—but more top teams being capable of beating anyone. Saban has always either conquered, or invented, every new trend in college football, from the spread offense to modern recruiting, but this will all be a shock to the system for even the best coach of all time. For the first time in college history, there are roster building shortcuts that everyone can—and should—use if they want to compete.

I read a quote a few months back from Coach K in John Feinstein’s book, The Legends Club, where he explained that, by 2013, the concept of a “young team” in college basketball had ended entirely. “Your team is your team. Period,” he said. The Duke basketball icon decided he had to coach one-and-dones the same way that he coached players who were going to be there for four years, and adjust to the shifting tides of his sport.

The last 20 years have been the great swerve of college hoops, where coaches who figured out what was happening quickly and built programs around it won, and those who didn’t were left behind. A similar shift is happening in college football. The sport’s top talent will not be one-and-done in college, but they might be one-and-done in a specific program. Evaluating, recruiting, and developing those players in a short window is going to become the lifeblood of the sport.

In a video last month, 247 Sports’ Bud Elliott explained why the transfer portal will be the craziest it’s ever been this year. One reason, certainly, is the widespread misevaluation caused by the chaotic 2021 recruiting class, when in-person recruiting was basically wiped out by COVID. But the biggest reason is that the 2021 class was the first before NIL factored into the equation, meaning most of these players have not been paid legally for (wink wink) their name, image, and likeness on what amounts to an open bidding process. Many will want that now—for some, that will mean staying at their current schools; for others, going to a new spot. This group will include, as Elliott said, star quarterbacks who are getting seven figures to play. However wild you think the portal will get, it will be wilder.

NIL for high schoolers will not dramatically shift the balance of power in recruiting—it will see the rich get richer, which was a trend that was well underway before NIL. But the transfer portal combined with NIL will change just about everything in the sport. USC played this game most famously last year, snagging presumed Heisman winner Caleb Williams and reigning Biletnikoff Award winner Jordan Addison from Oklahoma and Pittsburgh, respectively. In its 2022 transfer portal recruiting rankings (yes, those exist), 247 ranked USC first and LSU third, and both markedly improved by adding multiple blue-chippers. Williams, Addison, and LSU quarterback Jayden Daniels are one category of transfer: established starters from Power 5 schools who are ready to start immediately. But then there is a different group, highlighted by Florida State’s Jared Verse, who was one of the best pass rushers on the FCS level in 2021 at Albany, then transferred to FSU and saw his draft stock shoot up by showing his skills at a higher level.

Anyone who can improve their lot by transferring will, and should. Taking advantage of that fact will soon become the biggest edge in college football—and no rule says players from Alabama, or Georgia, or Michigan are exempt from trying to improve their lot, too. The future may include huge names going from one blueblood to the next. Alabama already added two stars this season in former Georgia Tech running back Jahmyr Gibbs and LSU cornerback Eli Ricks. And when Ohio State’s Ryan Day said $13 million in NIL money will be required to keep the Buckeyes’ roster together, he was talking about being ready for what’s about to happen.

Who survives college football’s vibe shift? Probably the same teams that thrive in this current era. Fan bases that can pay up in NIL already support the teams with the most resources and greatest history of attracting players. Coaches like Saban and Smart, who have a long track record of developing NFL stars, can probably get players for less by emphasizing the pro trajectory. But what this new era will do is open up the potential for college football’s age of miracles: All it may take is for one team to hit on 4-5 transfers, or one blueblood to lose their quarterback in a bidding war, for an entire conference to be upended. In a sport built on years-long plans, there is now the opening to do the football version of a get-rich-quick scheme with your roster. This is a net positive for players (and a lot of coaches), but it will not go smoothly for every program.

Alabama tells the story of college football every year, and will for the foreseeable future. And this year, they were beaten by two transfer portal quarterbacks—Tennessee’s Hendon Hooker and LSU’s Jayden Daniels (who was far more hyped than Hooker, mind you)—and two coaches in Josh Heupel and Brian Kelly who knew how to put a roster together quickly. None of this is to say that Saban can’t or won’t do this; it’s to say that the more unpredictable the sport becomes, the more Alabama, which thrives on discipline, process, and predictability, loses its well-earned edge. Between 2011 and November of this year, Alabama had played 164 straight regular-season games in which it had a shot at the national title, according to Chris Fallica. This time, though, even an apocalyptic championship game weekend in which fourth-ranked USC and third-ranked TCU lost was not enough to move a two-loss Alabama into the playoff. This was simply not a normal year. But we may not have those anymore.

It’s possible that when Alabama’s run ends, no one will be there to replace them. For good reason. Alabama passed a threshold very few teams passed, becoming a team that stokes the fires of college football anger. In every era, there are teams that are so good for so long that you remember where you were when they lost. When FSU lost its first ever ACC game in its 30th game in the conference in 1995, I was so young and so confused that upon waking up to the news after the night game, I asked my mom to repeat it three times because I couldn’t believe it. That kind of team. The kind of team that every opposing fan rushes the field over beating, and that the underdog campus bookstore spends a decade selling photos of the aftermath. Nebraska in the early ’90s. FSU in the late ’90s. Miami in the 2000s. If they are in a one-score game, get to your TV.

That’s been Alabama for over a decade now, and that will still be Alabama next year and probably the year after that. What I’ve been wondering recently, though, is whether Alabama is the last of those teams. Georgia is historically great, and producing NFL players at a wild clip, but they still have a ways to go. Smart has built a program in Saban’s image and succeeded wildly. And Saban’s coaching tree, even from 2015 alone—Smart, Billy Napier, Mario Cristobal, Mel Tucker, and Lane Kiffin—has produced a number of incredibly wealthy coaches who tried to build their own mini-versions of Alabama.

But maybe no one is built to succeed Alabama in the future. Maybe the concentration of recruiting among the top teams will spread players out among say, 10 teams, and the portal will determine the rest on a year-to-year basis. There’s an unfounded fear that somehow all of these changes will turn college more into NFL culture—a little less player passion, a little less fan fury—but I don’t see that happening. The battle lines between schools are already drawn, and players can learn to hate someone quickly: Verse, for instance, threw the “U down” symbol against Miami this year despite being a one-year transfer to FSU and product of Pennsylvania high schools. Players will always care.

What I do see happening, though, is roster-building becoming more like the NFL: It’s easy to plug holes and take double-digit new players now, meaning a program can change wildly from one year to the next. That kind of turnover means less linear player development from one year to the next, which means it will be far more unpredictable who will be at the top of the sport unless one team pays far more or one team becomes portal evaluation gods. I’m just guessing because everyone in college football is guessing right now. No one knows what’s going to happen. Thank God we’ve already got the coping mechanisms.