With WarGames matches—the logistics and history of which have been covered extensively around these parts by people much smarter than me—debuting on WWE proper at tonight’s Survivor Series, the first tangible piece of the Levesqueian revolution will finally come to pass.

That Triple H (as Vince’s replacement, Paul Levesque, is more commonly known) has done so with a promotional centerpiece that isn’t just an homage, but an explicit reimagining of the signature creation of McMahon’s most significant creative rival—Dusty Rhodes—says more about the future of the WWE then maybe it’s meant to. While the totality of the change which has happened in the roughly three and a half months he’s been in charge has been monumental, the distribution of its impact has made the whole thing feel less like an industry-historic sea change that will remake the medium over the next five to 10 years and more like a relatively subtle rebranding. (For wrestling, at least.)

While Triple H’s talent acquisition strategy is about as subtle as (sorry) a sledgehammer, he also shifted the presentation of the underlying assumption about the kind of entertainment the company produces and—by extension, in both literal and figurative ways—the connection it has with the larger world of wrestling. And he’s done so without explicitly (or even implicitly, by and large) acknowledging a change ever happened on screen. There’s just a certain je ne sais quoi surrounding the show; we all know things are different, a lot different—it feels better—but it’s difficult to find a point-source solution simply by watching the show.

Thankfully, we have numbers that go beyond what things feel like and get down to brass tacks:

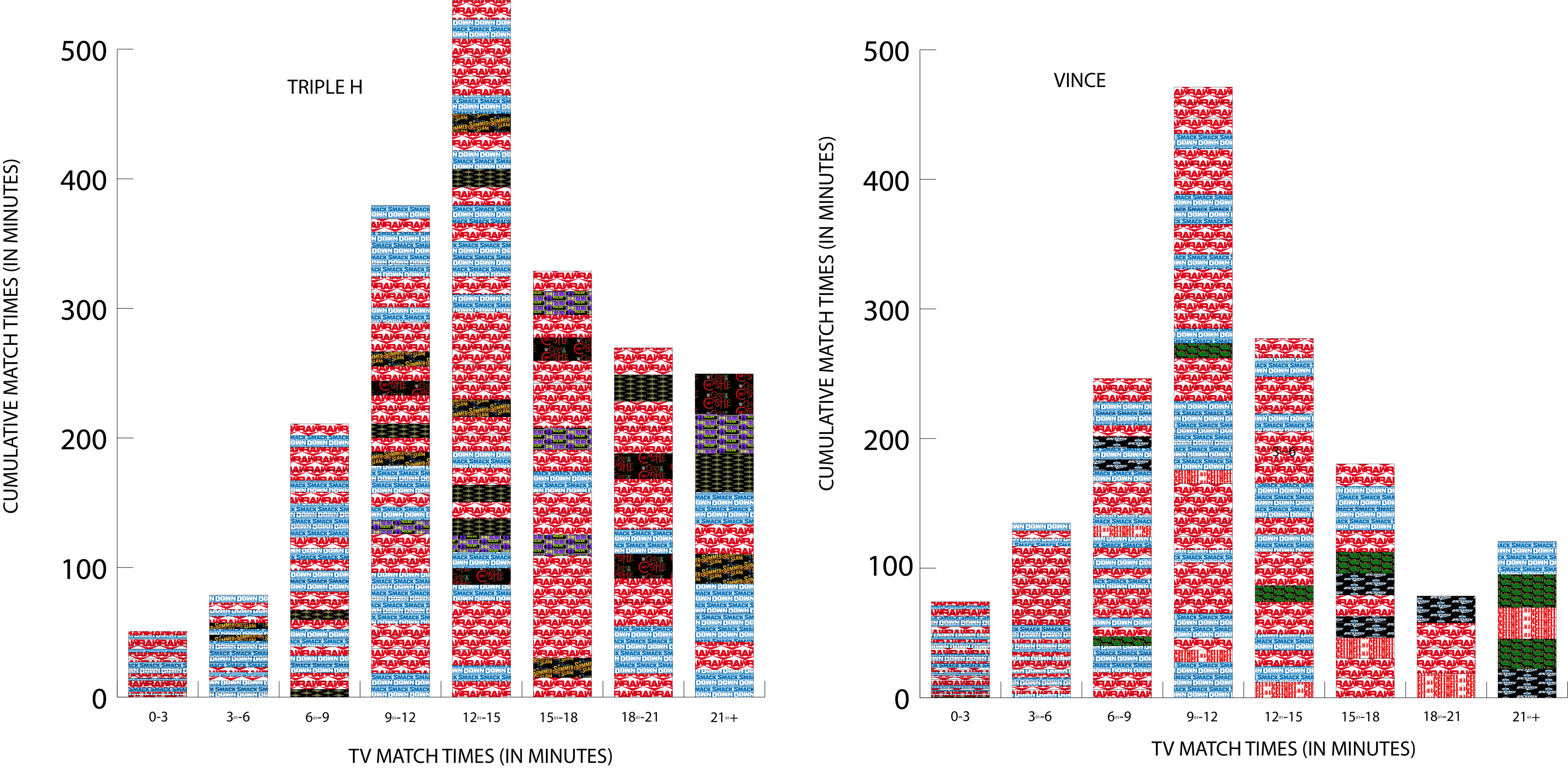

Since his first official night on the job—July 30’s SummerSlam—through November 11’s SmackDown, Triple H’s shows (which came out to 15 episodes each of Raw and Smackdown along with four premium live events: SummerSlam, Clash at the Castle, Extreme Rules, and Crown Jewel) featured EIGHT MORE HOURS of wrestling than Vince’s did, despite McMahon running almost exactly the same number of shows in the same timeframe.

Even taking into account an extra show for Triple H—Vince’s window included “only” three PLEs (WrestleMania Backlash, Hell in a Cell, and Money in the Bank) as well as the 15 episodes each of Raw and SmackDown, for a total of 33 shows to Triple H’s 34—something becomes clear looking over these cards. The difference between the shows isn’t simply a matter of one small variation accumulating over an extra-long period of time.

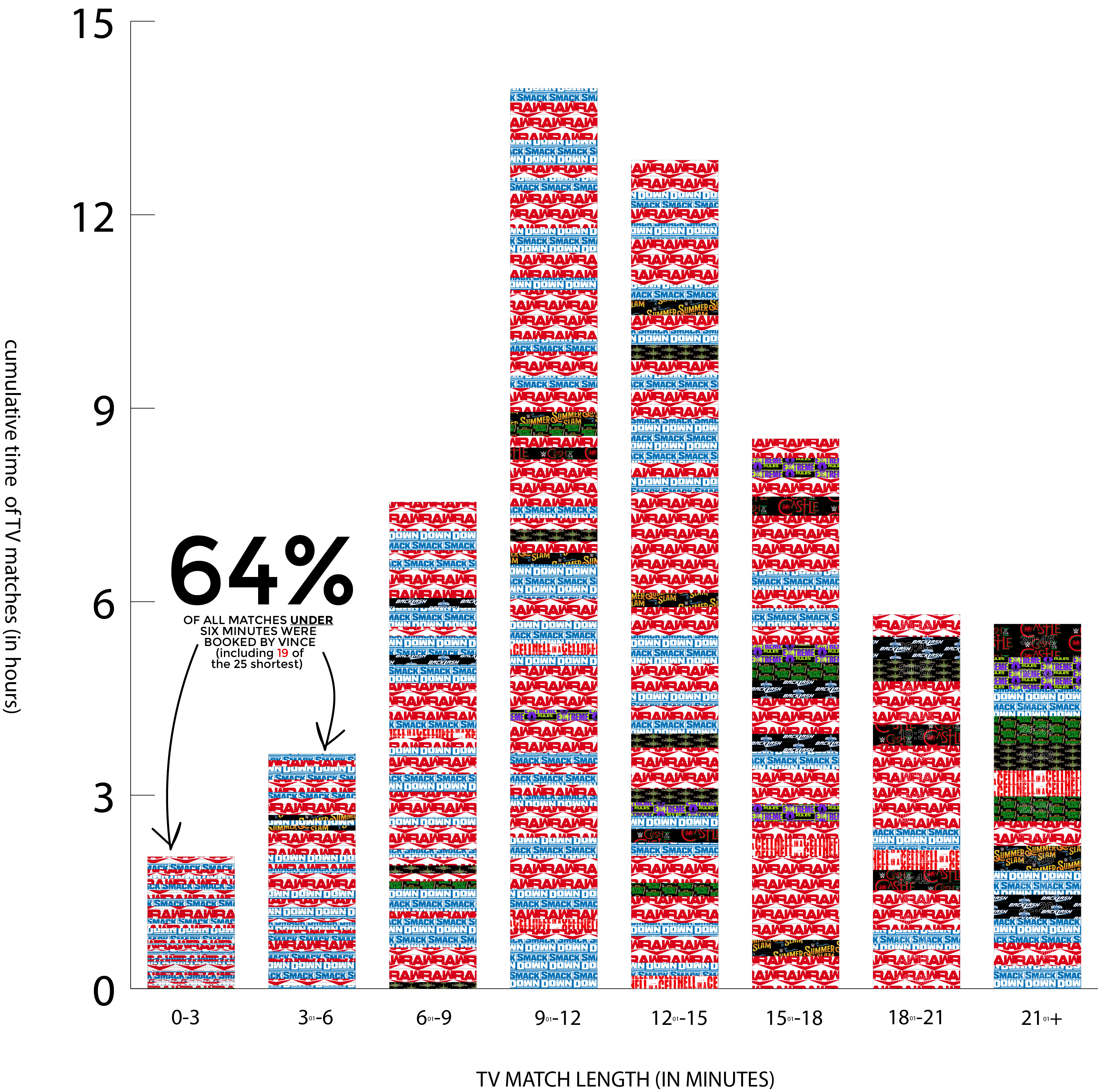

These numbers (and all the ones that spring forth from them) highlight two fundamentally different approaches to what exactly they were producing. While Triple H is ostensibly creating and presenting a wrestling show on TV, Vince’s approach to professional wrestling (or as he would insist, sports entertainment) television seemed to be slowly turning his media property into late-period MTV, where a distaste for putting music on their channel led to Ridiculousness becoming the opiate of the masses. The differences become a bit clearer when you can visualize how much emphasis they put on various match lengths (which, by extension, correspond to how many segments of television they are willing to dedicate to a given set of performers):

While it may be slightly difficult to parse at first glance because of the cumulative effects of longer matches, a closer look reveals McMahon’s almost pathological need to put on short matches. This obsession with breaking the land-speed record for a wrestling-match finish created an environment where there was a near 80 percent chance that a Vince match picked at random would last less than 12 minutes, and a 40 percent chance of one lasting less than six minutes.

Despite less time devoted to wrestling and one less show on which to do so, McMahon also managed to book one more match (192 total) than his successor, which seems to prove what we’ve known for the past few years: McMahon spent the twilight of his television-producing career trying to figure out exactly how many pounds of content he could stuff into a single show, and/or in the case of certain episodes, just how little in-ring wrestling he could get away with while still maintaining the veneer of sports in his sports entertainment product.

As you can see, when combined, the overall distribution of times is fairly normal. But Vince’s bookings dominate those matches on the shorter end of the spectrum. Although his matches make up “only” 64 percent of all those under six minutes—which is still a lot, but not so overwhelming as to skew the entirety of the enterprise leftward—when focusing on the shortest 25 bouts booked by either man, 19 (or more than 3/4) of them are McMahon’s. If this were part of some kind of larger model for engagement or viewer retention—i.e., if short matches on TV led to longer matches at premium events, thereby incentivizing people interested in such things to watch on WWE’s streaming platform, Peacock—such short wrestling matches might make sense.

But, of the longest 20 matches, only three—two of which are Money in the Bank matches, the only (inherently longer) multi-person PPV matches covered in the survey—were McMahon’s. It takes pushing past the top 40 to get to the point that McMahon’s matches start to account for more than one out of every five. And then, only barely: Of all the matches 12 minutes or longer, just 29 percent were McMahon’s.

There are reasons this makes sense structurally—more matches mean more entrances, which leads to less in-ring time (particularly on the TV shows)—but “logistically this makes a lot of sense” is not exactly a spoonful of sugar to help the medicine of Veer Mahaan matches go down. Mahaan’s seven matches under Vince, which lasted just about 20 minutes total—almost 50 percent of which came from one match against Dominik Mysterio—are perhaps the apotheosis of McMahon’s late-career MO for introducing new characters: meaningless squash matches that eventually build a monster character.

Folks like Veer—who is totally fun in the ring when not made to work like the second-to-last heavy in a low-budget action movie and has acquitted himself well since heading back down to NXT—appearing seven times on various wrestling shows just to do a sitcom episode’s worth of work would be much less of a bummer to watch if it were part of some kind of larger initiative to infuse the main roster with new talent. And Vince McMahon’s booking philosophy of volume-shooting short matches—matches which were, on average, two minutes and 41 seconds shorter than they have been for the last few months—would lend itself to develop new talent.

By giving a wider variety of performers a chance to tease out what they have to offer to the audience without forcing fans to commit to a quarter-hour of the match, you give newcomers “playing time” in low-leverage minutes. As such, it would seem to follow that Vince might include more performers on his show as a way to make new stars and establish new brands.

It may shock you, dear reader, to learn that this was not, in fact, the case. (In the 192 matches booked by McMahon, he used 13 fewer performers than Triple H in his 191.) All of which is to say that, from a purely statistical standpoint, Vince McMahon put far less emphasis on the marketability of his core product in and of itself, and seemed to have no desire in developing new talent or trying new things, which is usually a problem for a media mogul, especially if, for example, they are running a company that specializes in a specific field that is coming out of the most unusual time in its modern history.

Vince McMahon always had a bit of an aversion to pure professional wrestling as a commodifiable product category, but looking at the broader trends before the pandemic hit and now, it’s obvious that something broke or shifted with Vince’s approach to the show he put on week to week. With no ability to gauge responses to character developments and/or in-ring performances, you’d have to assume that the carefully calibrated ear Vince had developed to properly convert crowd response into screen time atrophied and left him tone deaf when fans started to make their way back into arenas.

Fan reaction over the last few months of his regime reached a nadir in the beginning of July, when the July 8 SmackDown featured five matches that averaged two minutes and 44 seconds each, for a cumulative 13 MINUTES and 40 seconds of wrestling which, for reference, is less wrestling than 58 of the matches booked by Triple H. (It is DEFINITELY a coincidence that this poorly received episode happened on the same day the Wall Street Journal dropped their story that would eventually lead to Vince’s resignation.)

The episode garnered a 1.3 (out of 10) rating on Cagematch, a self-selecting group of wrestling nerds. That number constitutes the lowest rating for any WWE event in the last five years, outside of the (very bad but also “review-bombed”) Saudi show at which Goldberg beat the Fiend in under three minutes, and an episode of 205 Live from the beginning of the pandemic where Brian Kendrick highlighted matches important to his career. (Including, apparently, the Hogan-Warrior main event from WrestleMania VI? The pandemic was weird.)

That episode of SmackDown may have been the beginning of the end of Vince McMahon’s time in full control of the day-to-day operations of WWE. Although the evidence is circumstantial, there is a noticeable uptick in television time devoted to wrestling and a concurrent decrease in the number of matches produced, with two of the most wrestling-intensive episodes of Raw and the most wrestling-intensive episode of SmackDown emerging in the aftermath of the July 8 fiasco. Perhaps even more indicative—as some of the least wrestling-centric (in terms of total matches) SmackDowns happened between July 8 and July 29—is the average match length, with three of the five shows with the longest average match coming in the same time period.

That’s not to say that Triple H was secretly in charge before Vince left, but the evidence at least suggests that someone with enough leverage asked Vince: “Now, eventually you do plan to have dinosaurs on your dinosaur tour, right?” But, unlike Hammond, the control Vince had, to that point, over his creations wasn’t an illusion.

Once he began to lose control—either of his ability to know what the fans were looking for or to dictate exactly what was going to appear on his television cameras—it seems very likely that Vince saw this as the beginning of the end of his time with the company. For Triple H, however, it seems to have created an opportunity to test out some of the experiments he developed in NXT while turning WWE into his version of Jim Crockett Promotions circa 1985.

Because, for all the assumptions made regarding what his influences have been, anyone who saw the Attitude Era (in which Triple H came to prominence) can surely tell you that the “crash TV”-style presentation that made that epoch famous has little to no influence over Triple H’s current in-ring product.

The clusterkerfuffle that was WWF’s late ‘90s booking—a quick survey of the last 30 Raws of 1998 shows just seven matches longer than 10 minutes and just one of those lasting longer than 15—is quite simply the worst regularly televised in-ring product in the history of our great nation, but I’ll be damned if it didn’t get SUPER over. This was, in large part, because of the “far more invigorating and extemporaneous” programming that Vince promised in his “Cure for the Common Show’’ promo (the most important two minutes in the history of wrestling television) that mostly happened outside of the ring.

When given the context of actual competition—in the form of AEW (and, to a lesser extent, an expansion of New Japan’s presence in the U.S.)—a shift in focus made sense for Vince. And of all the periods to retreat to as a way to present the show, it’s understandable why Vince picked this tactic. It allowed WWE to not play to the strength (which is to say, you know, good wrestling) of their “opponents” and accentuate what they do well. However, instead of going with the “good” parts of the show (the emphasis on the two pillars of storylines, motivations, and stakes) that made his most prosperous period work, he decided to focus on the part that became popular because of factors fundamentally impossible to recreate in this era, like the constant streams of blood and sexual objectification of women.

But, while it seems the lessons Vince learned from that time period were, “When you have competition for your wrestling company, you should definitely do less wrestling because that’s what makes your wrestling show special... the not wrestling,” Triple H appears to have picked up on the “multilayered storytelling that makes the universe which the show inhabited feel alive and organic” aspects of the Attitude Era (which sucked, but in the way spoiled milk does, not in the way a flesh-eating disease might).

For Triple H, the work in-ring uses the same formula as his peak in NXT: “old school” epic in-ring storytelling (nearly every single match has a non-repetitive narrative purpose) told through the prism of modern independent wrestling. In the same way Dusty Rhodes sought to tell stories from the old Westerns he watched as a kid through professional wrestling, Triple H looked to the things that made him fall in love with the idea of telling stories. This also happens to coincide with the democratization of wrestling, as streaming services provide outlets for all but the most independent of promotions in the industry. The rise of fandom as the primary mechanism regulating the flow between entertainment and commerce puts Triple H in a unique position.

The WWE has a chance to move past being a company that produces a unique brand of sports entertainment that exists both separately and above its contemporaries and sit at the forefront of an entertainment medium consistently creating new fans—through birth (you’re welcome/I’m sorry, Thisbe) and the magic of friendship buttressed by an all-inclusive mentality both in terms of those who participate and what kind of fans it can attract. Which is to say, WWE has the chance to create wrestling fans at a time when wrestling is as “cool”—or at least not actively uncool—as it will likely ever get, as opposed to taking the (much less sustainable) tact of trying to expand the number of people in the “WWE Universe”.

Lapsed WWE fans can come back (albeit rarely at the same level of dedication or interest), but wrestling fans mostly never leave. For almost the entirety of Vince’s tenure, WWE played an Atlas-esque role—in the Greek Titan variety, not “Tony who worked for Titan Sports” sense of the word—in the galaxy of professional wrestling, but has for nearly as long pretended like much of what happened outside of WWE simply did not exist. Part of this was McMahon’s well-established (and aforementioned) aversion to being a producer of “wrestling” shows, but it also seems to involve a fear that he’d be unable to differentiate his wrestling product in such a way to compete with other promoters, an infliction which Triple H definitely does not suffer from.

While the kind of shows that Triple H produces won’t have us living in some frictionless utopia, they are ones that highlight what the company does, seemingly without fear that they’ll look less-than in comparison to other organizations more confident in the primary product they’ve been created to sell. Which, with a GOD, a Visionary, the Man, the Almighty, and Eater of Worlds on your roster, that kind of ambition seems like a pretty good call.

Which is a good thing for wrestling fans, but may cause some problems for companies that, say, have the toughest ecstasy dealer in the history of Plainview High School as their world champ. (Good news everyone, New Max cusses!)

Nick Bond (@TheN1ckster) is the cofounder of the Institute of Kayfabermetrics and provides weekly updates to The Ringer’s WWE Power Board.