On Sunday, the series finale of The Walking Dead aired on AMC, spurring all but the hardest-core Deadheads to wonder, “Wait, The Walking Dead was still on?” It was, somehow; Robert Kirkman’s comic ended more than three years ago, but the TV adaptation long outlasted its source series and its own peak popularity, prompting persistent comparisons to its untiring titular monsters. But even the undead decompose, permanently impale themselves, or suffer fatal brain injuries eventually, and the series that gave countless extras screen time as shambling corpses couldn’t keep shuffling forward forever. After 12 years, 11 seasons, and 177 episodes, the TV institution that introduced audiences to Rick and Carl, Carol and Daryl, Maggie and Glenn, Morgan and Michonne, and several settlements’ worth of other mostly long-departed protagonists—not to mention a host of sadistic, tyrannical adversaries, from the Governor to Gareth to Negan to Alpha to Season 11’s new governor, Pamela Milton—is finally no more.

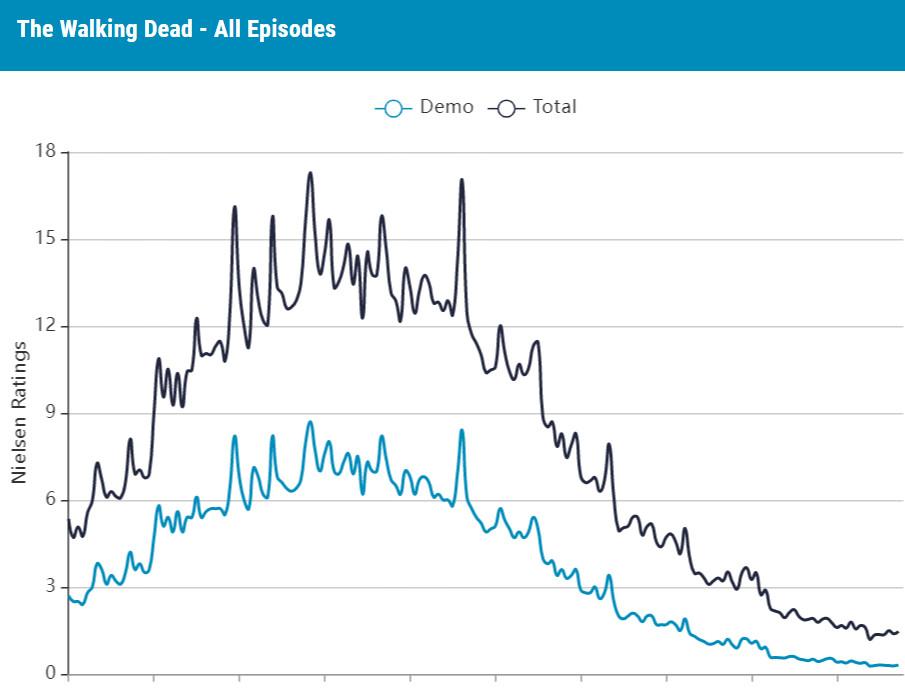

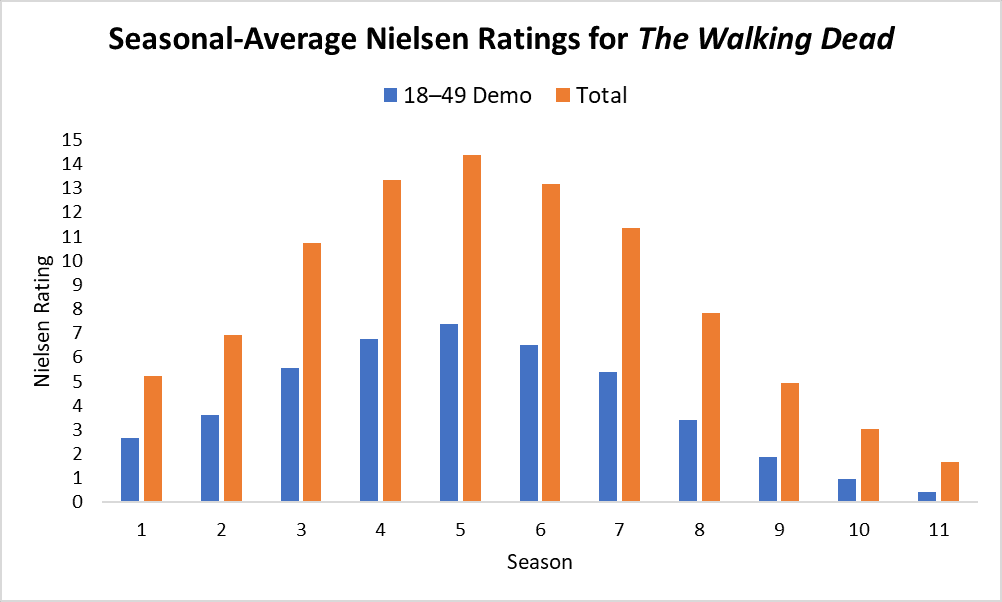

If a reanimated corpse falls in a forest in Georgia and no one is watching, does it make a sound? The Walking Dead has generated less and less noise in recent years, as its viewership and cultural salience have ebbed. Once, though, the show was a juggernaut. It premiered in October 2010, a different time for TV, when fellow AMC series Breaking Bad and Mad Men were midway through their runs, cord-cutting was a fledgling movement, and the first Netflix scripted original was more than a year away. Early seasons offered a frequently watchable blend of creature feature and golden-age drama with existential stakes, courtesy of an ever-popular postapocalyptic setting. As the creative reins passed through the hands of four showrunners and fan-favorite characters came and went, The Walking Dead’s quality waxed and waned in frustrating fashion, fluctuating from pulp to prestige and silly to serious from episode to episode and season to season. The series’ linear ratings first skyrocketed and then crashed, a consequence of variable writing, repetitive plotting, and the industry’s shift toward streaming, which saw the series’ back catalog added to Netflix and new episodes premiere on AMC+.

Despite The Walking Dead’s latter-day decline, the series leaves a large legacy. It spawned a still-extant franchise and remade AMC into a Walking Dead delivery system responsible for one completed spinoff (The Walking Dead: World Beyond), two active spinoffs (Fear the Walking Dead and Tales of the Walking Dead), and at least three future spinoffs slated for 2023 (The Walking Dead: Dead City, featuring Lauren Cohan’s Maggie and Jeffrey Dean Morgan’s Negan, and the self-explanatorily titled Daryl Dixon and Rick & Michonne). It helped usher in an era in which shared universes based on genre IP would become the calling cards for networks and streaming services: Game of Thrones for HBO and HBO Max; Marvel and Star Wars for Disney+; Star Trek and (most) Taylor Sheridan shows for Paramount+; The Boys and The Lord of the Rings for Prime Video. It kickstarted the aftershow trend, launched a wave of zombie shows and comics adaptations, established big- and small-screen stars, and became a very visible example of increasing cast diversity on TV. And for better or worse (depending on the episode), it told an expansive story, one that followed in the footsteps of the comic without always being beholden to it.

I’m not sure how it happened, but I’ve been in a long-term relationship with The Walking Dead, which (amid its trio of spinoff setups) played against type with a mostly optimistic, sentimental series finale. Only two characters from the first season lasted continuously to the end: Carol (Melissa McBride) and Daryl (Norman Reedus). Here’s how far back I go with this show: I’m a husband and a father who took my time getting to the altar and delivery room, but I met Carol and Daryl before I met my wife. It’s been years since I unequivocally liked the show, whereas I still like my wife. But out of hate or habit, I’ve kept watching The Walking Dead anyway, and my sunk cost has kept climbing. Genesis says God created the heavens and the earth in six days. I’ve spent more than seven days watching The Walking Dead, and that’s excluding spinoffs.

The upside to my mostly misspent time with this franchise is that I’m qualified to weigh in on where it went wrong. So what was The Walking Dead’s problem, and why did much of its audience desert the series long before the finale? Explanations abound: Was it Glenn’s brutal death? Was it Glenn initially not dying? As someone who regrettably stuck with the series in sickness and in health—and who, I confess, has also seen every episode of every Walking Dead spinoff, save for the second half of Fear Season 7 (which even I just couldn’t continue)—I think I’ve isolated the true vector of infection. Like the latent virus that turns the dead into undead, The Walking Dead’s undoing was lurking inside the series almost from the start: The walkers were too slow. And judging by recent events in the flagship series and its spinoffs, AMC knows it.

Zombies, by default, are slow and stupid. They moan and stagger and get thwarted by walls, doors, and ladders as surely as by blunt-force trauma to the head. The Walking Dead’s zombies have gone by dozens of nicknames (though never just “zombies,” in the show), but with few exceptions, they were always easily avoidable and outsmartable. These weren’t “fast zombies,” à la 28 Days Later; Kirkman quickly put that notion to rest, writing in response to a reader question at the end of the comic’s second issue, “I think you’ll agree that as the book goes on it will have almost nothing in common with that movie.” Neither did the TV adaptation.

The zombies’ advantage is that they don’t sleep or feel pain. Like Walking Dead spinoffs, they just keep coming and can overwhelm the living when they congregate in groups. However, once you’ve seen survivors mow down undead by the thousands, new close encounters don’t seem so scary. Even hordes posed fewer problems for our heroes once they started regularly wearing walker guts or skins so they could blend in with the undead crowds. And in isolation, walkers hardly looked dangerous at all, given that walking away from them at a modest pace was usually a sound survival strategy—one that not all characters were wise enough to employ.

On the surface, that doesn’t sound so bad, because The Walking Dead, its name notwithstanding, was always centered on the living. As Kirkman wrote in the 10th-anniversary edition of his comic’s first issue, “The zombies are a backdrop, and this is really an attempt to tell real stories abut how real people would deal with survival.” Or as Lori and Rick/Shane’s daughter Judith narrates in Episode 20 of Season 11, “The only thing more dangerous than the dead is the living.”

But to maintain tension, justify the protagonists’ (and antagonists’) desperation, and ensure that gore guru Greg Nicotero could keep squishing skulls, the zombies had to keep killing people. “If you weren’t killing characters constantly, I feel like it would be unrealistic,” Kirkman wrote in the 10th-anniversary reissue. But slow, hapless walkers killing experienced survivors on screen was unrealistic, too. By one accounting, more than 1,300 named characters perished on The Walking Dead, many of them having been bitten or torn apart. And their deaths seemed less and less plausible as the series progressed, the survivors grew more seasoned, and the zombies grew more decrepit.

To orchestrate the continued killing, the series’ writers forced their characters to hatch more and more ridiculous plans, made them do dumber and dumber things, or broke with Walking Dead convention by, for instance, turning normally slow, loud zombies into silent assassins that struck out of nowhere. “You don’t have to constantly keep watch,” Rick’s wife, Lori, says in the second issue of the comic. “They’re not that fast. A glance in all directions every five minutes will do it.” One would think! (Easy for me to say from the comfort of my preapocalyptic couch.) On screen, though, those zombies sporadically become surprisingly stealthy.

Who could forget the Season 2 death of Dale, so transfixed by a cow carcass that he failed to see or hear a walker approaching in an open field:

Or Jimmy, who died on Hershel’s farm because he neglected to lock the RV door:

Or Andrea, who had two free arms and a pair of pliers but couldn’t take down one walker:

Or the random dude in the Season 4 finale who stands around waiting for his face to be eaten instead of just walking away:

Or the typically cautious Tyreese, who zones out and gets chomped by one child-sized walker in Season 5:

Or Carter, who falls prey to a one-handed grab from a quiet zombie that’s hiding behind a tree in the Season 6 premiere:

Remember Barnes, the Alexandrian who’s bitten in the back two episodes later by a ninja zombie nobody sees coming?

Or one of Wade’s men, three episodes after that, who wanders right into biting range of a teeth-gnashing zombie that’s trapped behind a rock?

What about the scene from the same episode in which Tina inexplicably falls and lies down next to two not-quite-melted zombies?

Or a classic from the first episode of Season 9, when Ken gets bitten from behind by a previously invisible walker, after a bunch of badass zombie-killers—including Daryl, Rick, Michonne, Maggie, Jesus, and Ezekiel—inexplicably flee from a smattering of walkers that they handily dispatch moments later:

That’s just a small selection of the series’ numerous avertible deaths, which kept piling up right up to the end. As recently as Episode 17 of Season 11, an armed and armored Commonwealth soldier—who was well equipped and well trained enough to make it through roughly 13 years of the zombie apocalypse—got ripped in half when (a) his jeep mysteriously flipped over in a flat field, (b) he decided to stand still instead of backing away from the walkers into the wide-open area behind him, and (c) the soldiers riding to his rescue shot everywhere but at the walkers surrounding their comrade.

“So many moments like this in TWD,” wrote one of many incredulous commenters on that last YouTube video. “The writers can almost never make a believable situation where someone gets overrun.” That’s partly on the writers, but it’s also partly a product of the difficulty of concocting a credible scenario where hardened fighters schooled in anti-walker combat get overrun by a low-IQ adversary they can easily outrun. When I spoke last year to Angela Kang, who joined The Walking Dead’s writing staff in Season 2 and served as showrunner of the final three seasons, I asked her whether the writers had ever wished that their zombies were faster or more capable, because it would make their monsters more menacing and thus their jobs easier. “It comes up every year in writers’ rooms,” she said, laughing. “Like, ‘Could we make the zombies do this?’ … Yes, of course we’ve thought about that.”

It didn’t have to be this way. Before Kang joined the show, The Walking Dead was steered by Frank Darabont, who developed the series and served as Season 1 showrunner, director, and writer. Under Darabont, the walkers were more capable than they would later become. “The truth is we hadn’t really figured out yet what the rules for the zombies were,” Nicotero recently said. At least some of the Season 1 walkers could climb fences and use rocks to break glass:

In addition, they could crawl and kneel…

…and even jog:

They also seemed to retain some memory of their former selves. In the pilot, an undead little girl continued to carry her doll:

And in Episode 2, Morgan’s walker-ized wife returns to her former home, peers into the peephole, and even turns the doorknob:

All of that went away when Darabont was fired at the start of Season 2, an acrimonious split that eventually led to lawsuits and a large settlement. Under Darabont’s successor, Glen Mazzara, the walkers were dumbed down and got a lot less athletic. For most of the remainder of the series and its spinoffs, Season 1’s “smart walkers” were nowhere to be seen—even among walkers that were freshly turned. “Don’t worry,” Kirkman had written in his second-issue Q&A. “We’re not going to have any intelligent zombies anytime soon … or ever … I mean, what’s the point?” For years, the TV adaptation’s writers adhered to the comic creator’s philosophy.

Until lately, that is. Last October, Kang told me, “We’ve had a pretty consistent type of zombie. But I think even within what we’ve shown, there’s some variation. And so sometimes I’ve been playing with variations this year. It’s interesting, because there’s so much talk about [COVID] variants right now. And we kind of always planned to play with certain variations of zombie.”

Now we know what she meant. Within the past year, the Walking Dead universe has belatedly brought back Darabont-style walkers—and teased an even more threatening strain. Last December, a stinger that followed the series finale of World Beyond shockingly showed a new variant, one that reanimates quickly (potentially even after being shot in the head, though that wasn’t conclusive) and can remember where its killer came from, run, scream, and forcefully pound on a door:

The scene, which wasn’t connected to World Beyond but featured a cameo by Dr. Jenner, Noah Emmerich’s character from The Walking Dead Season 1, was set in France, where the Daryl Dixon spinoff is set to take place. All signs point to Daryl encountering zombies that behave more like those of 28 Days Later—not walkers, but runners. (Scott M. Gimple, chief content officer of the Walking Dead franchise, cryptically hinted that what we saw in that tag wasn’t the walker’s “end state.”) The scene also alluded to a group of French scientists—who may have been responsible for the creation of the runners—traveling to Ohio, where The Walking Dead’s Commonwealth is situated.

A week before that stinger aired, in the eighth episode of Fear the Walking Dead Season 7, Alicia follows a walker that she thinks can lead her. And this past August, in the fourth episode of anthology series Tales of the Walking Dead, a doctor reports seeing a walker repeatedly kill animals and leave them for the herd behind it. That set the stage for last month’s 19th episode of The Walking Dead Season 11, in which Aaron, Jerry, Lydia, and Elijah are attacked by an old-school “smart walker” that can open doors, pick up rocks, and climb.

“We’ve all seen some that come back to the places that they remember,” Aaron explains, after fending off the offensive. “I’ve heard stories about walkers like this that can climb walls and open doors. I was never sure if they were just stories. Maybe there’s other kinds too.” In the series’ penultimate episode, the smart walkers return and overwhelm the Commonwealth’s outer defenses…

… and Negan, upon seeing one in action, speaks for the audience when he wonders, “What the fuck?”

“This will be a grand finale that will lead to new premieres,” Gimple said of Season 11. “Evolution is upon us.” But in the case of the smart walkers, which met a fiery end in the finale, this wasn’t so much an evolution as a throwback that retconned the aberrant behavior of the Season 1 walkers while adding a wrinkle to the original series’ last gasp. “It’s almost like it was a variant that just was regional,” Kang said, attempting to explain where these walkers were for the last 10 seasons. The fast walker from the World Beyond coda, meanwhile, has “everything to do with the past and future of the Walking Dead universe,” per Gimple. Maybe, AMC is suggesting, zombies have to walk before they can run.

All of this feels far too late. AMC may view the variants as a means of reviving the flagging fortunes of its flagship franchise, but can old zombies really learn new tricks? These last-minute, tacked-on tweaks to the template of the network’s signature creature only highlight how much more compelling, convincing, and consistent the core series and its spinoffs could have been had the walkers never slowed down. “You know, it’s over,” Andrea told Dale in The Walking Dead’s Season 1 finale. “There’s nothing left. Don’t you see that?” Dale didn’t: “I see a chance to make a new start,” he said. Neither of them lived much longer. We’ll soon see whether AMC’s zombie empire is on its last, lurching legs, or whether the Walking Dead universe can outlive The Walking Dead.