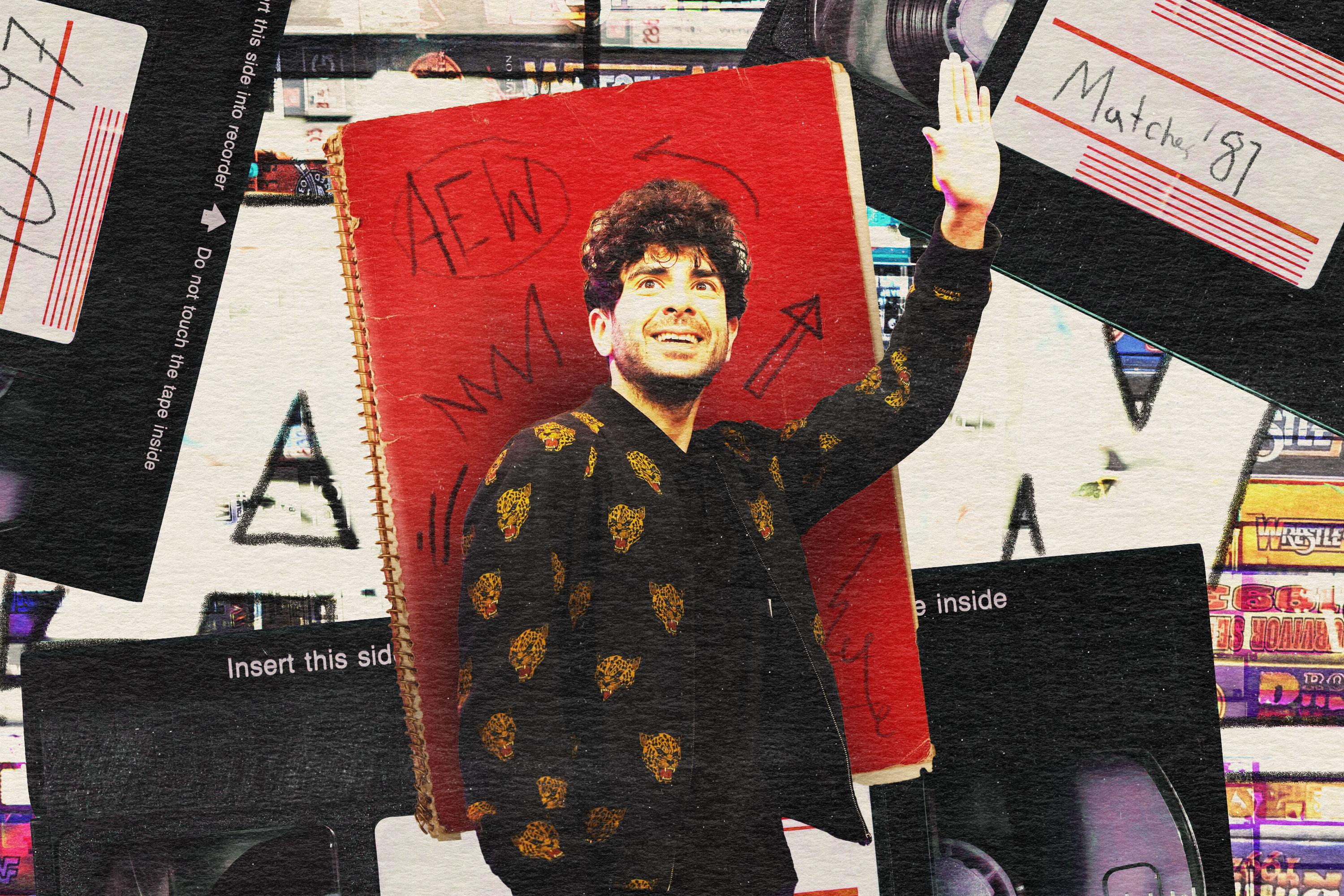

As All Elite Wrestling’s founder, co-owner, president, CEO, general manager, and head of creative, Tony Khan makes no bones about the fact that he is absolutely living out the fantasy of a childhood wrestling superfan.

“This would have been at the very top of things I’d have wanted to do when I was a kid,” said Khan during a phone call earlier this week to discuss AEW’s upcoming Full Gear pay-per-view event, scheduled for Saturday, November 19. “Honestly, to be able to have wrestling programs on TBS and TNT, I wouldn’t ever have thought it was possible. It actually exceeds a childhood dream.”

No one can reasonably accuse the 40-year-old Khan of being ignorant of wrestling history, and he understands the implausibility of the overlapping scenarios that ultimately placed him at the helm of AEW. That doesn’t mean that Khan wouldn’t have explored an alternative means to situate his own company onto the professional wrestling landscape, but he recognizes how strange it is that things ultimately materialized the way they have.

“I probably would have aimed for TV networks that didn’t have wrestling,” noted Khan. “If you told me when I was a kid that there would be a time when there was no wrestling on TBS and TNT, and that we would be the ones doing it, I would have thought we’d somehow bought WCW. And then if you explained to me how it actually happened, I never would have believed you in a million years. It’s crazy that WCW went out of business, and it’s crazy that TBS and TNT got out of the wrestling business for that long.”

As preposterous as it may all seem at a distance, the circuitous path to AEW’s creation and eventual materialization before an international viewing audience mirrors the atypical route taken by its founder and chief creative mind. Somehow, Khan infiltrated a business that most accepted leadership figures are either born or reluctantly adopted into, and now directs the foremost domestic rival to challenge World Wrestling Entertainment’s once decisive supremacy.

The story begins innocently enough. Like many people his age, the 7-year-old version of Tony Khan became a wrestling fan during the tail end of the Hulkamania era. In Khan’s case, becoming a professional wrestling fan was a simple matter of following the heroes from his favorite television programs back into their natural habitat.

“I had a television in my room, and I watched a lot of live-action shows and cartoons. One of my favorite live-action shows was The A-Team, and one of my favorite cartoons was G.I. Joe,” explained Khan. “The host of G.I. Joe was Sgt. Slaughter. He was also a cartoon character, but you knew it was a real person because he hosted the wraparound as the live-action host of the show. I also watched The A-Team a lot, and Hulk Hogan appeared as a friend of the A-Team a couple times. Then I saw more commercials, and saw that these guys also fought on another show, and on the other show it seemed like they weren’t the actors in a TV show; it seemed like they were actually going to have fights. I was really interested in it, and then I started to watch the World Wrestling Federation and became interested in wrestling.”

Khan quickly became a loyal viewer of the WWF’s syndicated weekend programs: Superstars and Wrestling Challenge. From there, he worked his way over to a tape of the 1990 Survivor Series before taking in his first live wrestling pay-per-view in the form of 1991’s Royal Rumble. In both cases, Khan can still recall the orders of the matches on both shows with the certainty of a child who watched the recordings of the shows hundreds of times until the tape had worn completely off the reel.

“The first match on Survivor Series ’90 was the Warriors—which was Ultimate Warrior, Kerry Von Erich, and the Legion of Doom—against Mr. Perfect and Demolition,” recalled Khan. “That I remember, but the first thing I remember watching live was the Rockers versus the Orient Express at Royal Rumble ’91, followed by the Barbarian versus the Big Boss Man, and Sgt. Slaughter versus the Ultimate Warrior. The first time I remember being on the edge of my seat with false finishes and run-ins and stuff was Sgt. Slaughter versus the Ultimate Warrior, which was a great match. When Randy Savage interfered, they built up to it with that whole self-contained pay-per-view story, which is also the first wrestling angle I really remember.”

From there, Khan took a deep dive into 1980s WWF. In the process, he found himself retroactively becoming a diehard fan of Ricky “The Dragon” Steamboat and “Macho Man” Randy Savage.

“There was a pay-per-view they had around December of ’91 that was like a best-of clip show. I think it was less money than the regular pay-per-views,” said Khan. “I think it was called ‘Hot Ticket.’ I think they did two of those. One was ‘The Best of Hulk Hogan’ and the other was ‘The Best of WrestleMania.’ The one that was the ‘Best of WrestleMania’ I watched, and it had Savage-Steamboat from WrestleMania III and a lot of other matches. Around that time I also rented all of the old Wrestlemanias and a lot of the NWA pay-per-views. I’ve watched that match from WrestleMania III so many times. They’re like two sides of the same coin that I go back and forth on. Certainly, when I think of the Macho Man, I immediately think of Ricky Steamboat, too. I still watch that match every year. I really love it.”

Khan’s budding fandom of Ricky Steamboat came at a curious time when he noticed that the same wrestler was being presented solely as “The Dragon” in the WWF without his traditional forename and surname. In Khan’s case, this made it all the more refreshing when Steamboat returned to World Championship Wrestling’s programming on Ted Turner’s stations, for which Khan had also rapidly developed a fondness.

“One of my first big pops was when Ricky Steamboat came back to WCW in 1991,” said Khan. “I’d just turned 9 years old and felt like I was already a grizzled fan, because I’d already watched so many shows on old tapes, and had caught up on a lot of older wrestling over the course of a year. When Dustin Rhodes brought out his mystery partner to take on Arn Anderson and Larry Zbyszko in November of ’91, when he took the mask off and it was Ricky Steamboat, I just went nuts.”

It was also around this time that Khan’s parents took him to attend his first live wrestling event, which was headlined by a match between the Ultimate Warrior and the Undertaker following an incident in which the Undertaker locked the Ultimate Warrior in a coffin. While Khan may have been thrilled by this improvement in his proximity to the action, his parents were less than thrilled with their only son’s latest entertainment interest.

“At first they were OK with it, but they kept telling me, ‘It’s not real. It’s not real.’ To be fair, neither were the shows they watched,” laughed Khan. “They were watching Designing Women and Evening Shade. Those weren’t real, either. Burt Reynolds isn’t himself in Evening Shade, and Delta Burke and Annie Potts aren’t really Designing Women. So I kept watching wrestling. My dad took me to that first show, but then I didn’t go to see another live wrestling show for probably five years after that. I tried to push countless times to either see shows in Champaign [Illinois] or in surrounding towns, but I never really got through to my parents. They were not supportive of it.”

The moratorium on live wrestling show attendance did little to quell the younger Khan’s appetite for wrestling action, which only intensified once he was granted access to dial-up internet.

“I’d learned a lot about wrestling every year and soaked up as much information about wrestling as I could from 1990 to 1994, and then the motherload hit when I started using dial-up services,” stated Khan. “I would get on the web in ’94 and ’95. I was definitely 12 when I got on Yahoo or Lycos and typed in ‘Is wrestling real?’ This thing came up pretty quickly on the rec.sport.pro-wrestling frequently-asked-questions page. It was this incredible treasure trove. Even then, a lot of it was pretty accurate as to how things are put together, who was in charge of what shows back then, what the wrestling companies were, who ran them, how they ran them, and how shows and matches got put together. I also got all these facts and real names, and a lot of history of incidents that happened in the business. It was all compiled under the frequently-asked-questions that I’d read many times and very quickly learned.”

The internet also accelerated the pace at which Khan was able to get caught up on wrestling history that he had been separated from by time, space, and parental prohibition.

“After I went online and started looking up things about wrestling, I became a tape trader,” remembered Khan. “I did HTML for one of the big tape traders—John McAdam—in exchange for tapes. That was my first job when I was like 12 or 13 years old. I really got into Mid-South, Memphis, Mid-Atlantic, Ric Flair, and Randy Savage. So with Savage, that meant watching a lot of old Memphis and older WWF. With Ric Flair, that meant watching TV from all over the place, with obscure promotions mixed in. Certainly everywhere from Florida and Georgia to Mid-Atlantic, and the AWA, and all the various places Ric Flair had worked. Then Jim Crockett Promotions and World Class Championship Wrestling.”

In addition to following the career progressions of his favorite legends, Khan was also staying abreast of what was presently transpiring in the wrestling world in 1995.

“There was still some interesting stuff going on,” said Khan. “Smoky Mountain Wrestling was active, and I went back and watched the older Smoky Mountain shows from ’92, ’93, ’94, and some more recent Memphis. Also, the things happening in Japan were so exciting at the time; both New Japan Pro-Wrestling and All Japan Pro Wrestling had great stuff.”

One of the other wrestling promotions active in Japan at the time was WAR—which stood for “Wrestle and Romance” or “Wrestle Association R” depending on when you started viewing it. It was one of the two offbeat offshoots (along with Network of Wrestling) that emerged from the rubble of the failed Super World of Sport wrestling promotion, and WAR was the lone company to survive the bifurcation of SWS beyond the one-year mark.

It was through the viewing of WAR’s content that Khan first laid eyes on a wrestler who would one day become a cornerstone of AEW: Chris Jericho.

“The first time I saw Chris Jericho was in 1995 on a tape from July 7, 1995, against Último Dragón. That’s a very famous match, and it introduced me to Chris Jericho,” said Khan. “I understand that Eric Bischoff and Paul Heyman also first saw Chris Jericho in that match. It’s a pretty significant match in his career. I then got really into ECW, too. ECW had a bit of everything. Dean Malenko and Eddie Guerrero were in a rivalry when I started watching it. Not long after I started watching ECW, a lot of the people started showing up in WCW. Dean Malenko, Chris Benoit, and Eddie Guerrero all turned up there. Then Rey Mysterio, Psicosis, and Juventud Guerrera also.”

The year 1995 is also retroactively distinctive in portending Khan’s improbable career trajectory for another reason: It is the year he began to explore the world of e-wrestling and instantly became addicted to it. Khan and his friends would draft rosters of fantasy wrestlers and script weekly wrestling shows built around the wrestlers they acquired, the territories those fictitious wrestling companies were headquartered in, and the eras in which they existed. Some of the hallmarks established during Khan’s earliest days scripting weekly wrestling shows that were usually browsed by only one fellow e-wrestling collaborator were successfully carried over to the small screen decades later.

“In 1995, I started doing an e-wrestling show called Saturday Night Dynamite, and then it moved around over the next many years. At one point in time it was on Monday night, but at one point it was also Wednesday Night Dynamite,” Khan said. “Then I used that name Dynamite for many years, and it had always been a steady thing. I relaunched the promotion with a new territory, new wrestlers, and new stories every several years. I wanted to try something different. The one thing that was always the same was that the weekly show was always called Dynamite.”

Dynamite has historically been used to clear obstacles and forge new paths, but Khan would eventually remove impediments to make way for Dynamite. The following year, Khan would broker a deal with his parents only slightly less consequential than the arrangement he would make with them more than two decades later to spawn AEW and transition Dynamite into an authentic televised wrestling series.

“My parents had me take the Secondary School Admission Test as an admission exam to prove that I could get into the University of Illinois Laboratory High School, which was one of the most competitive public schools in the country,” said Khan. “My graduating class had the number one ACT test average in America. It was a smaller school; there were 56 kids in my graduating class, and I took the exam and did well enough to get in. Now my parents wanted me to go, which is not what they said when I took it. I felt like it was a real bait and switch, and I was pretty upset. I didn’t want to go, and I remember my mom crying about it in a McDonald’s parking lot. I can even remember which McDonald’s it was.”

Khan knew an opportunity when he saw one, and he quickly turned the situation to his advantage and capitalized on what then seemed like the unreasonable desire of his parents to direct his educational path.

“My parents basically told me that if I went to the school, they’d give me anything I wanted, so if I told them the one thing I really wanted, I would get it, and then I would go to the school, and it would be a win-win for everybody,” said Khan. “I ended up getting the one thing I really wanted, which was to go to Philadelphia for the ECW Arena show, and it was headlined by Sabu versus Rob Van Dam, and it was also Chris Jericho’s last weekend in ECW before departing for WCW. Jericho had a match Friday night at the spot show at the Lulu Temple versus Sabu, and Saturday night at the ECW Arena versus 2 Cold Scorpio, with the main event of Rob Van Dam versus Sabu in a stretcher match. For me, it was a really important night in my life because Chris Jericho became such a huge part of AEW, and that was an important weekend for Chris Jericho as he moved into the next step of the amazing career he’s had over 30 years in wrestling on top in some of the biggest promotions.”

As an attendee of University of Illinois Laboratory High School, Khan found himself fulfilling the role of the awkward outsider due to his unfashionable penchant for wrestling, which ironically materialized in his literal fashion in a very direct way.

“When I went to school in ’96, wrestling was such a huge part of my identity. I wore an orange Taz ECW shirt to school multiple times a week,” said Khan. “The other days, I was probably wearing my Antonio Inoki Peace Festival t-shirt that I had gotten from a tape trader. Probably three or four days a week, I’d either wear that Taz shirt, or that Inoki Peace Festival shirt, or a Darth Vader shirt and a Happy Gilmore shirt. That was like my entire wardrobe at that point when I was 13 as far as shirts went.”

Over the course of Khan’s high school tenure, wrestling underwent a series of changes that rocketed it back into the forefront of popular culture, and simultaneously upgraded Khan’s social standing amongst his peers.

“In ’96, it wasn’t really cool to watch wrestling, but in ’98 and ’99, everybody started watching it, and all of a sudden it was a cool thing, and I’d gotten in on the ground floor,” explained Khan. “People started asking me questions during the Monday Night Wars and the Attitude Era about what was happening, and who these guys were. On Tuesday mornings, people would be asking me why something happened, or what was the deal with whatever was going on. I really enjoyed it, and as I went through puberty and matured, I think the wrestling business went through its own crazy growth spurt as I was going through mine.”

As the 1990s gave way to the 2000s and then the 2010s, Khan continued to indulge his hobby of e-wrestling no matter where his life took him, whether it was to the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign, or into the world of legitimate business. Over that lengthy stretch of time, Khan scripted, timed out, and submitted more than 1,000 wrestling shows for his small audience of e-wrestling aficionados, while adding more content into the mix that would one day receive a tangible form.

“It was probably around 2011 when I wanted to do more great wrestling matches every week, so in my fantasy wrestling league I created a second show,” said Khan. “Incredibly, that was Rampage. I actually had a third show that never came to fruition, but it was kind of fun, and it was called Tuesday Night Tag Team Fights. I had these different shows, but Dynamite and Rampage were always the primary shows. I have done Dynamite since 1995 and Rampage since 2011.”

While Khan is quick to point out the differences between typical fantasy sports and fantasy wrestling leagues, along with the increased sense of connectedness and ownership associated with the latter, he is careful to warn people who think their e-wrestling experience is sufficient to prepare them to manage the real McCoy, even if those e-bookers have drafted more than 1,000 e-wrestling shows like he has.

“In e-wrestling, you get ideas and try stuff out. I was a really young kid; I’m not saying it was impactful, or that you can jump straight from that into the wrestling business, but it was definitely a fun way to get your reps in,” said Khan. “There are a lot of young coaches in the football business, and you’re not going to use fantasy football to make your decisions in the NFL, I can tell you that firsthand. But growing up, a lot of people in the NFL played fantasy football. There’s nothing wrong with it, but it’s honestly very different from fantasy wrestling. When you’re doing a wrestling show, there’s a lot more involved in putting stories and angles together week to week, and stringing things together versus setting a fantasy lineup. There’s actually a lot more involved in a fantasy wrestling league.”

One other thing Khan credits his time in e-wrestling with is its ability to condition him to write shows that speak to his sensibilities as a wrestling fan, even when the other fans he was writing for only filled seats in the arenas of his imagination.

“There was a guy who passed away years later who was in the fantasy wrestling league I was in with my regular e-wrestling friend, and I remember him saying this so well,” began Khan. “He said that we were writing for an audience of just each other, but in a way we were writing for 10,000 fans or 5,000 fans that were in the arenas of these imaginary shows. Somehow you can still tell when stuff is over or not over with the fans, which is funny because they’re not real! But he was right! My other friend and I had never articulated it like that before, but he was right. That spoke to me.”

Since the advent of All Elite Wrestling in 2019, the fans have been very real, and in an era of unparalleled access to the decision makers of wrestling by way of social media, Khan finds himself inundated with direct fan feedback on a daily basis.

“That’s been the biggest difference: Connecting with real people and seeing what they like, and balancing that with what I want to do. But frankly, I want to do it because I want to have a great promotion that the fans want to see,” said Khan. “I’m a big wrestling fan, and I want the other wrestling fans to like it. I do think I share tastes with a lot of our fans because I enjoy the shows too. A lot of the stuff they like, I also like, and if some of the stuff we put on the air doesn’t go perfect, I would probably agree with them that it didn’t go perfect. I like staying on the pulse of the online wrestling community.”

Not only are the fans real, but the wrestlers are real as well. To that end, even though he can legitimately lay claim to being the most successful e-wrestling promoter of all time, Khan believes he is fortunate to have acquired plenty of experience interacting with performers and personnel in other athletic ventures (Tony’s father is Jacksonville Jaguars and Fulham FC owner Shahid Khan; Tony holds executive positions for both franchises) to pair with the booking skills he acquired in the world of fantasy. The marriage of the two sets of experience served him well once he was fully immersed in the world of authentic professional wrestling.

“My experiences in pro sports, working in the NFL, and particularly as director of football for Fulham, I have seen that the difference between being a fan and working in the industry is that you have to be a people person, and also that people are the key factor,” explained Khan. “Just the simple act of telling people what they’re going to do is very different in real life when you’re dealing with actual human people and trying to get them to do things in a way that they’re actually going to feel good about it, whether it’s football or wrestling. You also have all these people with great ideas, but there are a lot of ideas that you can’t do, either because they’re not possible logistically, or the people are already involved in something else, so it doesn’t fit the schedule. Other times they’re just things you wouldn’t want to do. A lot of it comes down to trusting your instincts.”

On other occasions, dealing with real wrestlers means contending with real tragedies, like the untimely death of AEW star Brodie Lee in December of 2020. This devastating loss also generated a real-life moment that Khan considers to be one of his proudest as the owner of AEW.

“The Brodie Lee tribute show was the best thing we’ve ever done in the company. It was the hardest show ever to produce and put together,” said Khan. “For the wrestlers, I know it was a most difficult day, and for what Amanda, Brodie, and Nolan [Brodie Lee’s widow and sons] went through, it’s unfathomable what they’ve endured. I think the thing I’m proudest of is that we’ve had the greatest tribute show that anyone has ever done in the history of this business. If you watched that show, you come out of it saying, ‘That guy really loved his family, he really loved wrestling, and the wrestlers and his family really loved him.’ That was what we were trying to get across, and I think we did a very good job.”

One crucial inevitability that Khan says e-wrestling prepared him for is the reality that you simply can’t please all of the people all of the time.

“You very quickly start getting the sense when you actually sit down and write shows that you can’t please everyone,” said Khan. “You can’t get everyone you want to use on the show every week unless you’re putting 37-hour shows together. Also, everyone isn’t going to win every week. That’s just not how it works.”

In the meantime, Khan stands as an interesting counterpoint to longtime WWE boss Vince McMahon. While McMahon was mentored in the wrestling business by his father and devoted every fiber of his being to it, he was often criticized for willfully ignoring events transpiring in the wrestling promotions of his contemporaries around the globe. In contrast, Khan is a superfan who monitors and embraces the traditions of wrestling from all corners of the earth, and aspires to see all the elements of his fandom coalesce beneath the AEW banner. Perhaps no recent sight is more indicative of this than the image of Jun Akiyama—the final smoldering ember from the era of All Japan’s blazing match-of-the-year factory of the 1990s—squaring off against Eddie Kingston and Ortiz alongside Konosuke Takeshita in an AEW ring, live on TNT.

“It’s about finding the right people and finding the right fit,” elaborated Khan. “I’m not a chef, and I don’t know much about cooking, but I’d have to imagine that there are a lot of different ways to approach making the items that appear on a menu. In a two-hour live wrestling show, there are a lot of ways to put it together, just like there are a lot of ways to put together certain menu options.”

One thing has already proved to be true: Whether his wrestling audience is real or imagined, and whether the size of his fan base consists of two people or two million, Tony Khan will continue to churn out a steady menu of wrestling content, even if some of his detractors insist that his output is hard to swallow.

“In the end, I would say it’s really about connecting with your fans and finding different ways to serve them what they like,” said Khan. “There are people for whom it might not be their favorite thing, but if they were to see it in the right presentation, they might like it. I’m just trying to put our best foot forward, and trying to create a home for all of the best things in wrestling.”

And as meandering as the pathway to finding bona fide homes for his once fictional wrestling creations has been, Tony Khan has enabled professional wrestling to once again take up residence on TNT and TBS. He now writes for the entertainment of millions because he never hesitated to write for an audience of one.

Ian Douglass is a journalist and historian who is originally from Southfield, Michigan. He is the coauthor of several pro wrestling autobiographies, and is the author of Bahamian Rhapsody, a book about the history of professional wrestling in the Bahamas, which is available on Amazon. You can follow him on Twitter (@Streamglass) and read more of his work at iandouglass.net.