At some point during his time away from WWE controlling his own narrative, Braun Strowman apparently did enough good (or bad?) on the outside to earn a promotion if/when he came back to the company. After spending much of his career there as the “Monster Among Men” (and briefly “Mr. Monster in the Bank”), Strowman has been reintroduced upon his return to the WWE universe as the “Monster of all Monsters.”

This upgrade in status comes with a spot on next week’s Power Board, a trimmed-down physique, a seemingly rejuvenated joie de vivre, and a match at this afternoon’s Crown Jewel show in Saudi Arabia. (A “quick” aside: That last bit isn’t necessarily a good thing for Braun, and not just because of the looming threat of attacks by Iran. The history of the Saudi shows—which, for a number of reasons, is not something we’re going to spend much time looking at in broad strokes—has not been particularly kind to Strowman. Even his .500 record is seriously weighed down by his three-minute Universal Championship match loss to Brock Lesnar and his eight-minute count-out loss to Tyson Fury. Yes, the lineal singing heavyweight boxing champion.)

His return to WWE PPVs/PLEs pits him against Omos. But while this bout has been treated as a kind of “monster mash” between Strowman and the Nigerian Nightmare, the ways in which these two are built (and booked) speak to a fundamental difference in their roles with the company and the limitations that come with them, not just in WWE but across the overarching history of wrestling.

Strowman is a good ole-fashioned monster, as his nickname implies. Omos—a 7’3” former basketball player who exists as a kind of awesome idea more than as a professional wrestler—is the latest in a line of tall fellows looking to take on the throne of WWE’s resident Giant, a title originally earned (at least in the Vince Jr. era) by the titular Andre in feuds with the likes of Big John Studd and then passed through the subsequent generations to performers such as his son, The Big Show. These performers exist on a spectrum of... spectacular… ness (?), from “The Eighth Wonder of the World” to “The World’s Strongest Man” to “The Alpha Male of Our Species.”

While Omos hasn’t reached the same level of promotional hype, the fact that he doesn’t necessarily have to do anything impressive to be impressive has already gone a long way for him. He looks incredible (as in hard to believe or comprehend) just standing in the middle of the ring, as evidenced by his WrestleMania (and main roster) debut in 2021.

The match itself and Omos’s performance were monumental, both in the sense that his opponents (Kofi Kingston and Xavier Woods, representing the New Day) showed true artistry in turning a slab of granite into something resembling a work of art (closer to Dogs Playing Poker than Young Hare, of course) and that he mostly just stands in one spot the entire time while people watching ooooh and aah.

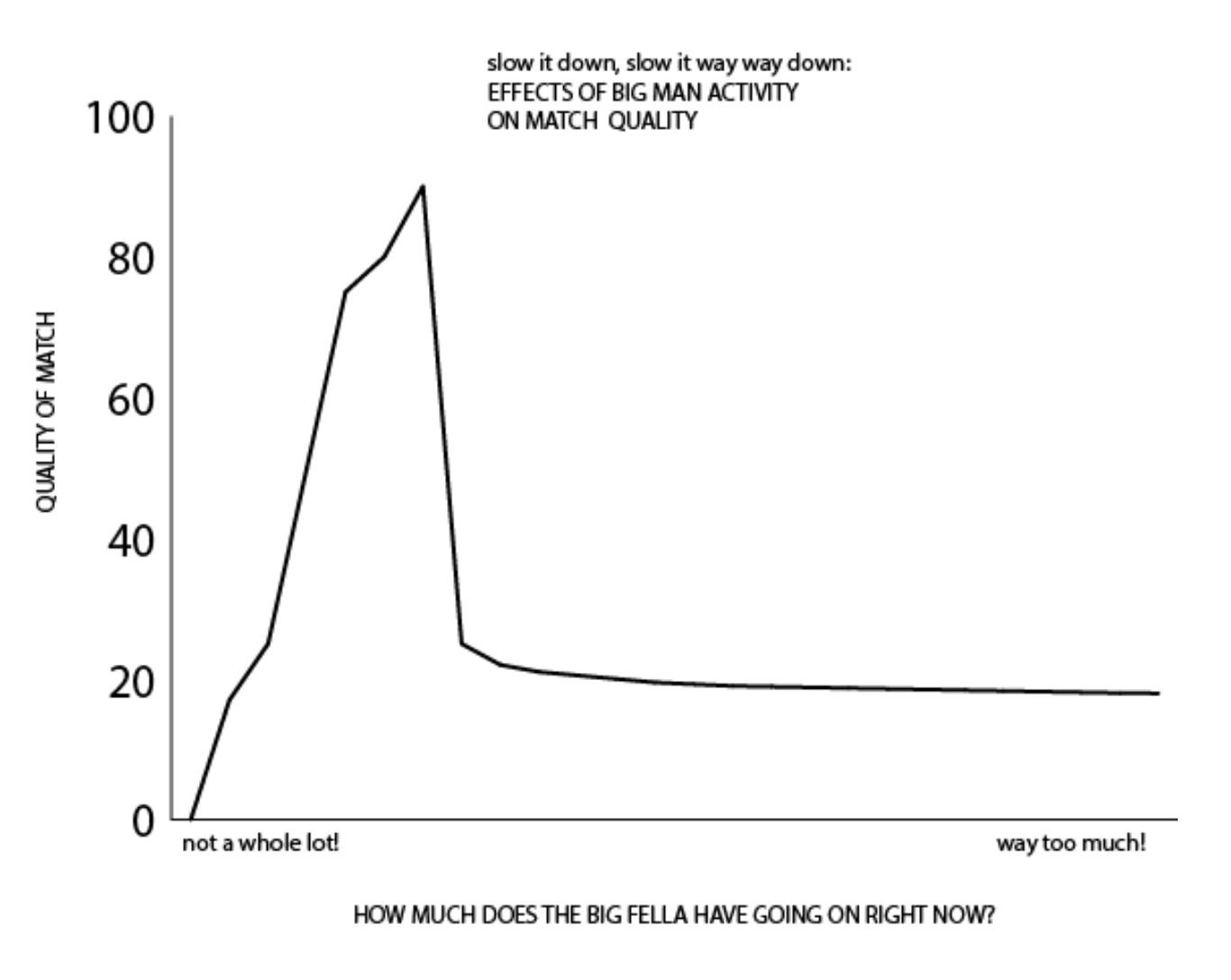

Which was what he should have done! Thankfully, the bigger you are, the easier that is to do. Counterintuitively, in terms of movement, the more you do when you are a larger competitor can end up making you look less impressive if things don’t go right. If there were a graph displaying the results of a mathematical formula for what big men should be doing in the ring, it would look something like this:

And, bless his heart, Omos hasn’t yet figured out how to get past “not a whole lot” and even have a chance at having “way too much” going on. To be fair to Mr. Omogbehin, he hasn’t had much time to learn either; that WrestleMania tag-team championship match (with three inner-circle Hall of Famers, including AJ Styles) was just his seventh match ever, and it’s not exactly like he’s been on some Drew McIntyre–esque pace over the last 20 or so months, with only 100 total matches (out of 106 for his career). Very slightly more than half of those have been on TV, but he’s only seen (just about) six hours of in-ring time on TV over that span—for an average match time (AMT) of 7:01, roughly one minute and 21 seconds less than Liv Morgan, the closest performer to Omos on the Big Board—which puts him at the shallow end (above, say, Logan Paul and Bad Bunny, but below almost literally everyone else on the roster) for full-time WWE performers.

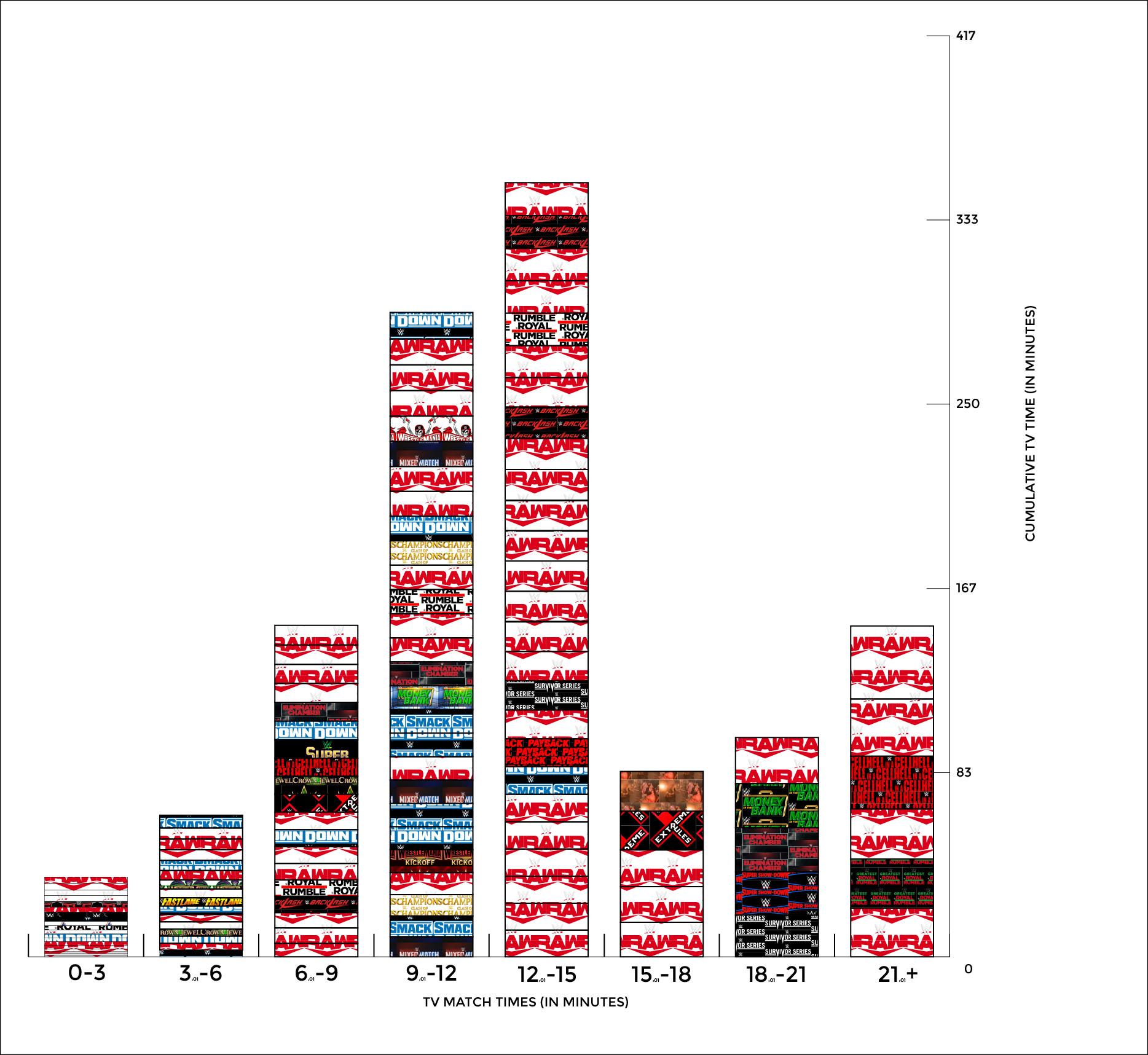

That’s at least until Strowman makes his debut following qualifying action (for him and Omos) later today with an AMT of just 7:05, but Strowman’s usage situation seems temporary. Historically, the former strongman has an AMT nearly three minutes higher (at 9:57) and a significantly different distribution of match lengths.

The way in which Strowman’s match lengths are dispersed is fairly standard and actually offers insight into the “why” of scoring for time in our system. It’s best to think of these different match lengths as different kinds of matches. Anything below three minutes is either a clusterkerfuffle or a squash; matches between three and six minutes are usually longer (read: less dominant) versions of the same thing or a performer getting a chance to prove themselves on TV (depending, usually, on the size of the performer); and six-to-nine-minute matches usually offer performers an extended chance to prove themselves, not infrequently as a lower card match on a PPV card.

From there, you get to the meat of WWE’s menu, with matches featuring 9–15 minutes of in-ring action making up most of WWE’s TV and PPV time. If those shorter matches are webisodes made to tell a more complete version of the world a longer-form series takes place in, matches of this length are the normal, full-length episodes that make up the bulk of the story being told about a given performer. As is the case with essentially everyone, these are also the kinds of matches in which Braun has spent (by several hours) the most time on our TV screens. After this, there’s a massive dropoff before the momentum of multi-man match participation brings the amount of time we’ve seen Braun appear in genuinely long matches (21 minutes or longer) in line with the amount of time we’ve seen him in those of the six-to-nine-minute variety (which is to say: a relatively small amount of time in terms of his actual action in contests with lengths that are almost entirely a function of the context of the time constraints of the show on which they take place).

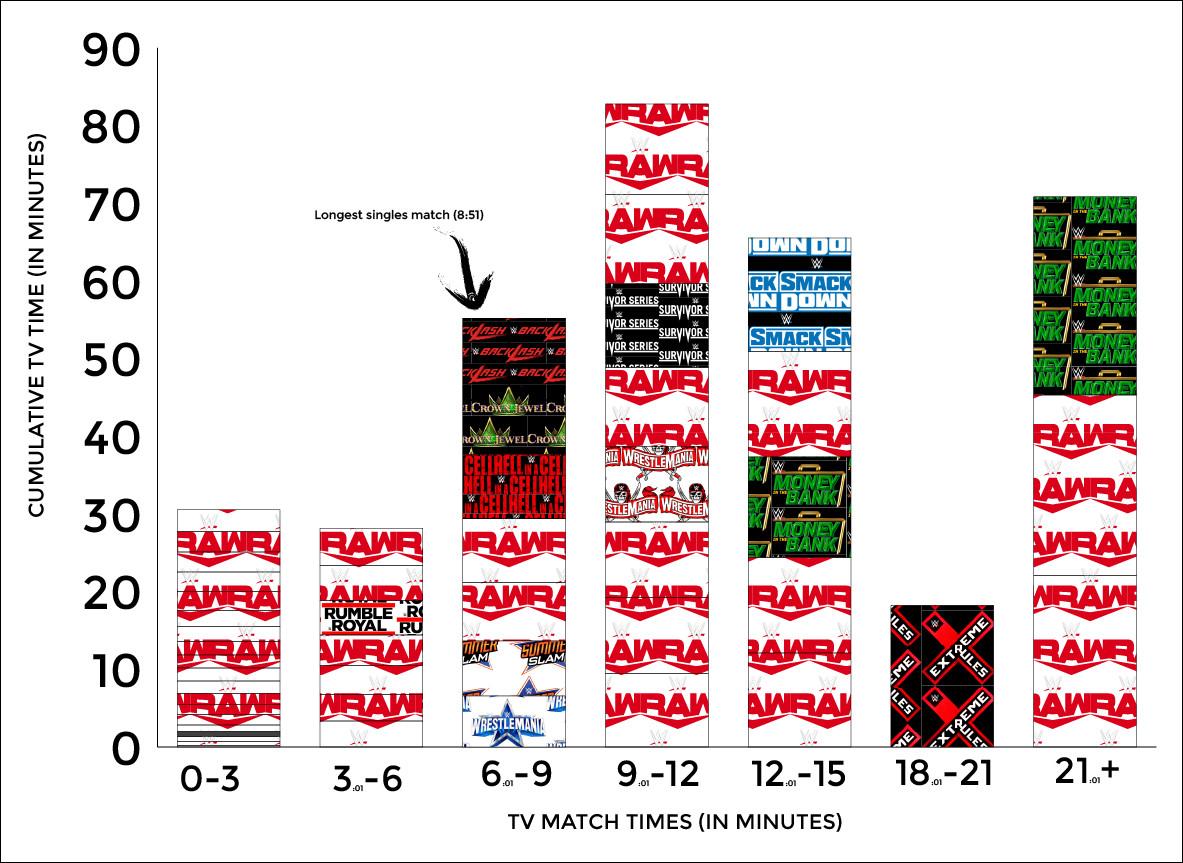

Contrast this with Omos, whose match length distribution looks something like this:

While they may seem similar at first blush, in addition to simply having no matches between 15 and 18 minutes, that bump on the left-hand side of things means that Omos spends more time on TV in matches under three minutes than he does in matches between three and six minutes or between 18 and 21 minutes. Omos is a particularly extreme example of this kind of booking, as he has literally no singles matches that have lasted as long as nine minutes. (For context, Braun has more televised singles matches longer than nine minutes [34] than Omos has televised single matches total [27]: nine handicap, 18 one-on-one.)

But Omos isn’t the only example of this disproportionate emphasis on “five minutes, including entrances” kind of matches, and our all-time favorite (non–Arn Anderson) professional wrestler in the Palace of Wisdom is the finest example of both the spectacular and monstrous from the world of professional wrestling: Big Van Vader.

Vader’s definitely not the first monster heel in wrestling history, though he’s certainly the first one of the modern era to get over in the way he did. Performers like Bruiser Brody (widely considered a master of the art form) simply did not have the success (in terms of championships) or exposure (in terms of TV time) that those who came after him did. This is largely a result of the shift in emphasis for the business from trying to create a mystique around performers that would entice fans to go to house shows (which is to say that the job was literally to put butts in seats) to selling a narrative on television that exists largely outside the role of the house show (which we extensively talked about last week).

While Brody was a bridge between Vader and those who terrorized the territories before him, like Gorilla Monsoon, Killer Kowalski, the Mongolian Stomper, or The Sheik, Vader served as a nexus of all the different facets of professional wrestling across the globe. These performers relied largely on the idea of what they could do if given the opportunity, not unlike Omos.

Performers like Brody, Vader, and now Strowman have made their bones based on what they would do. (Or, with Brody, with what should happen if he might refuse to do what’s asked of him.) And it worked: After his very first match as Vader, in which he squashed Antonio Fuckin’ Inoki, the fans were so upset there was a riot. Starting in 1987, he’d go on to dominate Japan—holding the IWGP Heavyweight Championship three separate times for a total of over a year—before finding his way stateside once his “conquering gaijin” act had begun to lose some of its juice even as he teamed with Bam Bam Bigelow (which was as dope as it sounds).

When he began working in the United States again, for WCW in 1990 (after a run in AWA with a name [“Baby Bull”] the man behind the gimmick, Leon White, hated, White then became an international star in Germany and Japan), he started off much the same way as he had in Japan, with a short match in which he dominated a cornerstone of the company in which he was debuting. OK, so, the first part is definitely true, as he won his first match in just two minutes and 16 seconds; but while we may have love for Tom Zenk in the Palace of Wisdom, the Z-Man did not a pillar make.

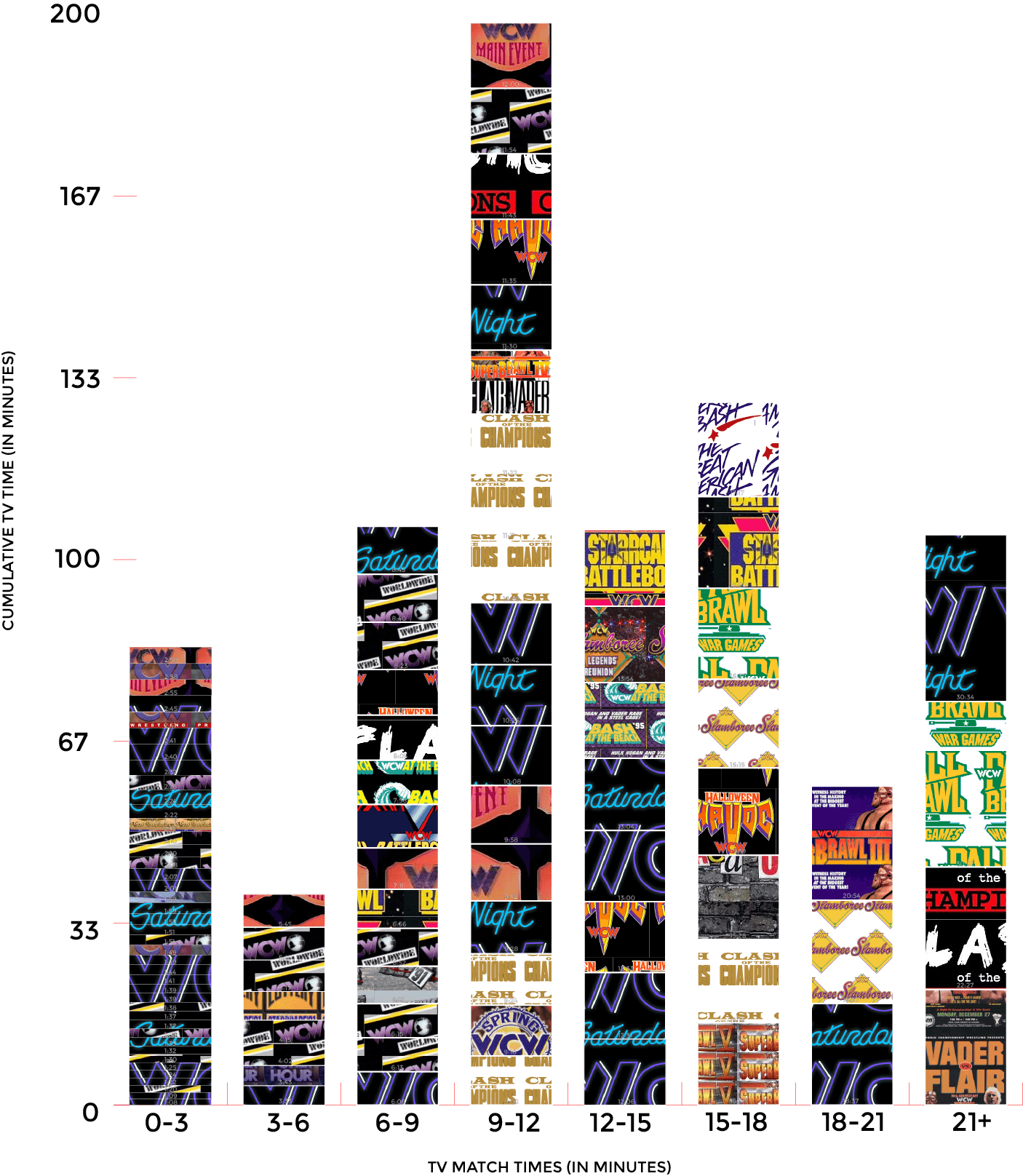

From there, Vader’s career in WCW on TV ended up getting broken down like this:

Vader’s leftward tail is the mountain by which Omos’s molehill shall forever be measured. The Mastodon’s run in WCW—especially before Hulk Hogan came and did all the Hulk Hogan shit imaginable—is so dominant that a new kind of match finish for our system came out of it: the Vader Squash, where a performer loses a match by DQ in less than two minutes. When you beat up someone so badly the ref feels like it might be cheating, that’s a push, and it’s now treated accordingly.

Between this and comically short handicap matches—Vader has a run immediately after beating Sting for the WCW Championship at the Great American Bash, where he wins four consecutive two-on-one handicap matches on four consecutive televised matches in less than eight minutes total—Vader was able to spend a full 10 percent of his career in WCW showing up for roughly a 7-11 trip’s worth of work to beat up ham-and-eggers. But what separated Vader from both Omos and Braun, as well as provided them both a goal to grow toward (as we assume they are both avid readers and members of the Power Board Pals), was what Vader did the rest of the time.

Now, he wasn’t pulling out Edge numbers, but it’s not a coincidence that several of his matches that went somewhere resembling the distance—like his match with Sting at Superbrawl III or his legendary match the next year against Flair at Superbrawl IV—are ones where he is featured in the main event against notoriously long-winded workers. Although he has some of the same peaks and valleys that both Omos and Strowman had in terms of the variety of matches they work, it’s these I AM THE BAT DAD bits of business that turned him into one of the absolute greatest monsters of all time.

Like so much Michael Myers, it wasn’t just that he could stab you with such force you’d hang on the wall, it’s that he could keep going through most of Halloween night and required heavy artillery, industrial equipment, or arson to be kept down.

In order to reach that level, though, Strowman must do a lot more in the realm of the kind of epic storytelling that WWE most consistently relies on to tell stories about its most powerful players. He’s worked cinematic matches, and he’s also at least been in the kind of blockbuster action set pieces that usually indicate big things (or toy cars) are coming your way. But his résumé needs more than one main-event match lasting longer than 20 minutes and even a handful more squashes like the one he had on SmackDown against four jobbers, working a “dueling banjos” angle with Omos after he did the same recently on Raw. (I would, for one, never tell a professional athlete like Strowman he needs to work on his cardio, but I’ve certainly watched enough wrestling to know that running around the ring while pretending you’re a choo-choo is a good way to blow yourself up, at best, and a great way to completely blow out your knee, at worst.)

It’s unclear whether Omos even wants to actually get to a spot like that, or just to where The Big Show hung out in the back half of his career with WWE, alternating between default heavy for any villain looking to force their way to the top (or keep their position once they got there) and “happy-to-be-there giant who may or may not do funny dancing.” Omos seems like a sincerely great person and a talented, charismatic presence who could certainly have the ability to connect with the crowd better than he may ever be able to get in the ring. But it’s hard to imagine a world in which he becomes the successor to someone like the Mongolian Stomper (especially because, as a Canadian, Archie Gouldie didn’t really seem like a believable Mongolian Stomper in the ’70s. So I’ve got to be honest, it’s hard to imagine a Nigerian man getting over with that gimmick in 2022.)

Especially if it requires him working in anything longer than 10–12-minute spurts that seem to be required now for performers at the top of the card (especially for those not named Lesnar) or even a division.

This isn’t meant as a way to question Omos’s stamina (or, by extension, potentially his willingness to improve it) but speaks to the revealed tastes of most wrestling fans when it comes to (at least in WWE) the kind of matches that Giants that double as Attractions most often do. We don’t want to see—and WWE almost certainly doesn’t know how to coherently tell a story about—a giant who is also the best fighter with the strongest will. But with monsters in wrestling no longer (and not for some time) being necessarily about what you could do, but what you can and actually do, there seems to be no way that Omos will be able to do enough while moving to be more impressive than when he’s standing still.

As for Braun, while it’s unlikely he’ll ever reach the Rocky Mountain highs that (again, seriously, one of the very best) Big Van Vader reached, that says way less about Adam Scherr or his place in the business than it does about Leon White and the perfect storm of brutal perfection he rode through wrestling between 1987 and 1996. Strowman will, or at least should—unless MVP gets involved, what with the cane and the chicanery on his side—win his match against Omos (we don’t make predictions in the Palace of Wisdom) and with that would certainly put himself on track to get back near the top of the card.

But even if he never gets all the way there, this seems to be a Braun Strowman (and Adam Scherr) even more willing to put in the work to get there and, after spending some time in the wilderness of independent wrestling promotion, a hunger to make sure he never has to leave WWE based on the decision of somebody else. And that’s about as scary a thought as I can think of. (Or, at least the second scariest.)

Nick Bond (@TheN1ckster) is the cofounder of the Institute of Kayfabermetrics and provides weekly updates to The Ringer’s WWE Power Board.