In some popular framings of the Houston Astros–Philadelphia Phillies World Series, which begins in Houston on Friday, the Astros are a well-trained, well-rounded, and well-built baseball team, impregnable and businesslike. The Phillies, by contrast, are a group of Gritty-looking misfits powered by beards and chaotic-good vibes, whose approach to the sport could best be summed up as just “crazy enough to work.” “Astros/Phillies is gonna be a wise samurai with a katana vs. a crazed lunatic with a machete,” went one viral formulation. “The Houston Astros are a perfectly engineered baseball machine of death no one in their right minds would challenge, but the Philadelphia Phillies are ‘That sign can’t stop me because I can’t read’ personified as a baseball team,” went another.

There’s some truth to the perception. The Astros are October regulars, having played in six straight American League Championship Series and won four; since they pulled out of their tank in 2015, their regular-season dominance is second only to the Dodgers’. The Phillies, whose post-rebuild clubs have struggled to surpass .500, had the majors’ second-longest playoff drought before they beat the Brewers by one game to claim the third National League wild card in this season’s newly expanded playoff field.

In theory, anything these Phillies can do, these Astros can do better. Behind Aaron Nola, Zack Wheeler, and Ranger Suárez, the Phillies led the NL in FanGraphs starting pitching WAR. Only one major league team surpassed them: the Astros. The Phillies, owners of the second-lowest combined bullpen WAR from 2019 to 2021, featured a dramatically improved, top-10 pen this season. The Astros’ pen ranked third in the majors and led the AL. The Phillies hit well; the Astros hit better. The Phillies, notoriously, are one of the majors’ worst defensive teams. The Astros are one of the best.

The Phillies made midseason moves to shore up that glaring defensive weakness by installing Bryson Stott at shortstop and trading for center fielder Brandon Marsh. But according to Statcast, their defense doubled the negative run total of the next-weakest unit even in August and September. (The Astros will test Philly’s fielding, too; as per usual, Houston batters make contact, while still hitting for impressive power.) On the whole, the Phillies picked up their pace after a slow start, posting MLB’s seventh-best record after a midseason manager change; over the same span, though, Houston had the third-best record. The Phillies, for what it’s worth, are hot, having gone 9-2 on their postseason path through the Cardinals, Braves, and Padres; then again, Houston is hotter, having swept the Mariners and Yankees to become the third team in the wild card era to win a pennant without dropping a playoff game. Unlikely as it is, the Astros could become the first team since the 1976 Reds—and the first in the wild card era—to run the table in the tournament.

So yes, this World Series is a mismatch on paper. One observer, alluding to Super Bowl LII, quipped that, “The Astros are the Patriots. The Phillies are the Eagles.” The analogy works, considering New England’s championship pedigree—but those Eagles and Patriots had the same regular-season records, and each was its respective conference’s top-seeded team. The Astros, the AL’s top seed, won 19 more games than the Phillies (the NL’s lowest seed) did during the 2022 regular season, the second-largest gap in any World Series. Thus, in addition to a talent edge, Houston also has home-field advantage.

All of which means … well, not nothing, but not as much as one would think. Though the Phillies aren’t an underdog in the spending sense—their payroll is a good deal higher than Houston’s—the Astros are obvious on-field favorites. But we’re talking about baseball, where playoff outcomes are so random and upsets are so common that they rarely require believing in miracles. The two teams with better records than the Astros after May, the Dodgers and Braves, were eliminated in the NLDS. The two previous teams to go undefeated en route to a pennant in the wild card era, the 2007 Rockies and 2014 Royals, lost in the World Series. (The Rockies got swept.) The only pennant winner with a bigger regular-season wins deficit than these Phillies relative to their World Series opponent was the 93-win 1906 White Sox—and they won anyway, defeating the 116-win Cubs. The Astros, for that matter, know what it’s like to lose the Fall Classic to NL East upstarts; the Nationals and Braves beat them in 2019 and 2021, respectively. And while we’re at it, the underdog Eagles won Super Bowl LII.

For the next four to seven games, it doesn’t matter that the Astros are perennial pennant favorites, while the Phillies are trying to extend a Cinderella run. It doesn’t matter that the Phillies’ roster isn’t especially homegrown or economical; fans care much more about winning than what winning costs owners, and the Phillies are still standing after the $/WAR leaders like the Rays and Guardians are gone. Nor does it matter that the Phillies don’t do the things that are often reputed to confer postseason success: play good defense; have a shutdown closer; put the ball in play and score without relying on homers; finish the season strong. (The Phillies went 14-17 to end the season.) There isn’t any secret to winning in October, save for being a better team, and even that helps only so much. Dependence on dingers might be one of the few factors that nudges the needle—and it’s actually better to be more reliant on the long ball. (Though unfortunately for the Phillies, Houston has them beat there too.)

No, all that matters over the next several days is which team plays better and gets luckier. All of those reasons to expect the Astros to triumph amount to a modest 58–42 edge in championship probability, according to FanGraphs’ ZiPS projections—not quite a coin flip, but close enough that you’d have to flip many times to tell the difference. (Baseball Prospectus’s PECOTA puts the two teams even closer; FiveThirtyEight’s system, based on full-season results rather than projections for the current roster, has Houston further ahead.)

The Phillies have already taken down three teams that won more regular-season games than they did, but the Astros figure to be their biggest challenge yet. To get this far, the Phillies took advantage of a few breaks: Cardinals closer Ryan Helsley’s stiff finger; Braves starter Max Fried’s flu; Spencer Strider’s long layoff (and Brian Snitker’s slow hook). They also capitalized on opportunities against vulnerable, back-end starters such as Charlie Morton, Mike Clevinger, and Sean Manaea. That’s no knock against the Phillies, who made the most of what they were given. But the Astros won’t give them much; they’re incredibly deep, and they offer their opponents few breaks or breathers.

By one measure, the Phillies’ depth actually compared quite favorably to Houston’s during the regular season. One way teams sabotage themselves is by giving ample playing time to sub-replacement-level players, when in theory better options should be fairly easy to find. This year, the combined WAR produced per team by sub-replacement-level players ranged from minus-1.3 (the Yankees) to minus-10.4 (the Reds). The Phillies, at minus-2.4, tied the Dodgers for the second-lowest total. The Astros’ total of minus-3.4 ranked fifth lowest.

Combined 2022 WAR From Sub-Replacement-Level Players

Still, it’s one thing to avoid players who drag you down; it’s another to collect players who really lift you up. The Astros sported more of the latter. That’s most apparent in their pitching staff, where even the weakest link—if you can find one—was and is still strong. Thanks in part to the team’s defense, only two pitchers on the Astros’ entire regular-season staff (Pedro Báez and Ronel Blanco) posted ERAs above the MLB average. That duo combined for a grand total of 8 2/3 innings pitched. Only one team since World War II has amassed fewer innings from pitchers with worse-than-the-MLB-baseline ERAs: the 1979 Orioles, who had zero. Those O’s, who used only 12 pitchers total (to the Astros’ 22), lost to the Pirates in a seven-game World Series.

Fewest IP by Worse-Than-Average-ERA Pitchers, Post-WWII

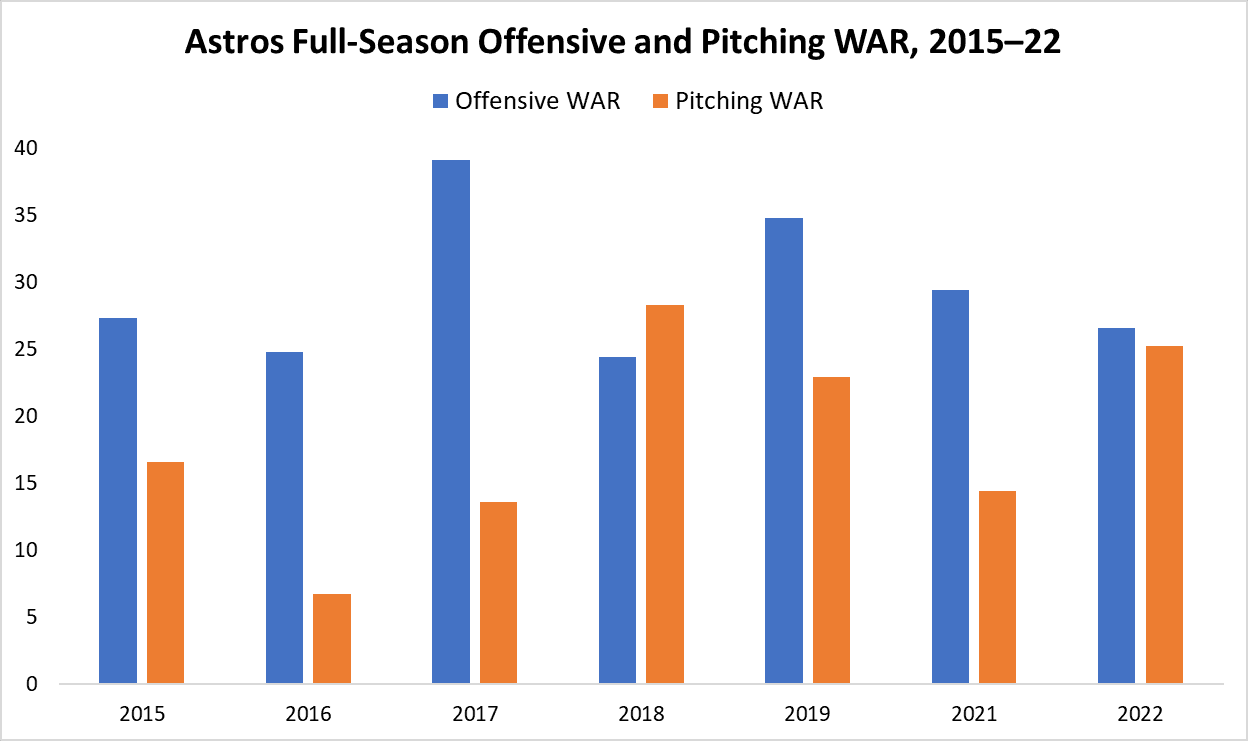

The Astros’ near absence of subpar pitching highlights an important point about this team, which is illustrated by the graph below of Houston’s offensive WAR and pitching WAR (per Baseball-Reference) in every full season since they returned to contention, excluding the pandemic-shortened 2020. This Astros club isn’t the offensive powerhouse that the 2017 and 2019 teams were; its offensive WAR total trails even those of the 2021 and 2015 models. However, its pitching is second only to the 2018 team’s. Overall, this isn’t the best Astros team of the era—that would be the 2019 juggernaut, which was also elite on defense—but it is the most balanced.

Reflecting their relative lack of prowess at the plate, the Astros have hit only .227/.300/.408 in the playoffs, which puts them second in OPS behind the Phillies among teams that have played more than two games. (Offensive firepower is scarce this postseason.) However, Houston’s arms have made up for the so-so sticks. In the postseason so far, Astros starters have been solid, recording a 2.77 ERA in 39 innings despite Justin Verlander’s uncharacteristic struggles in ALDS Game 1. But the bullpen has been obscene. In a postseason distinguished by dominant relief work, the Astros’ pen has been the best of all, throwing 33 innings and allowing only three runs (earned or otherwise), good for a 0.82 ERA. That’s the fifth-best postseason ERA any bullpen with at least 20 innings pitched has posted prior to the World Series in the wild-card era—and the four in front of Houston’s each totaled fewer frames.

Best Postseason Bullpen ERAs Before the World Series

A bullpen on a heater on the path to a pennant isn’t necessarily a lock to keep up its performance in the final round; the 1981 Yankees pen at the top of that list allowed 18 runs (15 earned) in 21 World Series innings, as New York succumbed in six games to the Dodgers. But it’s tough to envision this Astros group melting down like that. The ’Stros are so rich in relief options—and made such quick work of the Mariners and Yankees—that they’ve advanced with some arms tied behind their backs. José Urquidy, who was on the ALDS and ALCS rosters, didn’t pitch in either series; it’s a testament to the Astros’ strength that they could deploy Luis Garcia for five brilliant extra innings in ALDS Game 3 and still have a fresh quality starter waiting in the wings in case the game had gone beyond the 18th. Righty reliever Seth Martinez, who recorded a 2.09 ERA during the regular season, made the ALCS roster but didn’t see action either. Ryne Stanek, who had a 1.15 regular-season ERA, has pitched only two innings.

All told, the Astros have used only 11 pitchers this postseason. If they use two more in the World Series—perhaps Urquidy, who has four games of Fall Classic experience, and either Martinez or a lefty like Will Smith or Blake Taylor—they’ll tie their own record, set in 2018, for the most pitchers used in a postseason run in which every pitcher boasted a better-than-average regular-season ERA. (The 2020 Dodgers used a record 14 pitchers in the postseason who had better-than-average ERAs, but they also used one, Alex Wood, who didn’t.)

Most Pitchers Used on an All-Above-Average Postseason Staff

There’s a hidden advantage to rostering so many palatable pitchers. In October, teams pay close attention to the times-through-the-order penalty and tend to pull non-elite starters before they go deep into games and suffer from a familiarity effect that benefits batters. A similar penalty applies across games: The more times a reliever faces the same hitter within a single series (particularly a postseason series), the worse he tends to do. The Phillies, who have roughly three trusted relievers—Seranthony Domínguez, José Alvarado, and … let’s call David Robertson and Zach Eflin half-trusted relievers who add up to a third—run the risk of overexposure if the series goes six or seven games. By the time the most important plate appearances arrive, Houston’s hitters may have seen these pitchers a few times, which might make a small but pivotal difference. Astros skipper Dusty Baker can spread his team’s innings around without dramatically downgrading (not that he should take chances), so Houston’s highest-leverage relievers—Ryan Pressly, Rafael Montero, and former Phillie Héctor Neris—might maintain the element of surprise.

One point in favor of the Phillies is that unlike the Mariners and Yankees, they have the lefty sluggers—namely, Bryce Harper, Kyle Schwarber, and maybe Nick Maton or Darick Hall—to counteract the Astros’ righty relievers. Houston hasn’t rostered a southpaw pitcher aside from starter Framber Valdez this month, which makes the Astros the 10th pennant winner in the Divisional Era to make the World Series without using a lefty reliever—but the first to have done so despite playing more than five postseason games. The 1974 A’s, who beat the Dodgers to take the title, are the only one of those pennant winners to deprive themselves of lefty relief innings in the World Series as well. (A few other non-pennant winners—the ’85 Blue Jays, ’95 Reds, and ’05 Angels—played at least seven postseason games without using a lefty reliever.) The only other lefties who might surface for the Astros in this series are Smith and Taylor. That’s nothing new for Houston, which had the fewest batters faced by lefty relievers of any team this season. Not that the platoon disadvantage hurt them: Only Atlanta’s relievers allowed a lower wOBA (by one point) against left-handed hitters than the Astros bullpen.

Even so, Harper and Schwarber are huge power threats against opposite-handed pitching. Houston’s top arms are quite capable of handling lefties, on the whole, but the same could be said of the Padres’ Robert Suarez, and look what Harper did to him in NLCS Game 5. Harper has been the most fearsome offensive force in these playoffs—taking over that title from Houston’s Yordan Alvarez, who held it early on and could still snatch it back—and it’s likely that at some major moment of this series, he’ll have a crack at someone he can get a good look at. A healthy Harper at the plate, who until he turned it on in October hadn’t fired on all cylinders since he broke his thumb in late June, is the most convincing reason to think the current Phillies are better than their regular-season stats suggest. It doesn’t hurt that the Phillies feast on four-seamers, and the Astros throw them often.

The Phillies’ pitchers, meanwhile, figure to match up pretty well with the Astros’ lopsided lineup—save for the soft middle of Philly’s rotation. Houston hitters had the platoon advantage in only 40.5 percent of their plate appearances during the regular season, the third-lowest rate in the majors. That was with almost half a season’s worth of work from left-handed-hitting Michael Brantley, who went on the injured list just after Harper but, unlike Harper, didn’t return in time for the playoffs. The active Astros are extremely right-handed on offense also, with Alvarez and Kyle Tucker (who should face Alvarado often, familiarity effect be damned) the sole lefties, albeit big ones. Houston hitters had the majors’ second-best wRC+ against lefty pitching, but only the ninth best against righties.

That bodes well for the Phillies’ right-handed Game 1 and Game 2 starters, Aaron Nola and Zack Wheeler, who can start four of the first six games on full rest, or account for five of the seven if they start games 4, 5, and 7 on short rest. Phillies manager Rob Thomson may want to take a page out of Nats skipper Dave Martinez’s playbook from 2019, compensating for a thinner staff by riding his righty aces and four best bullpen arms as hard as he can. (Even if rest and/or rust were an October differentiator—which there’s little evidence of—it wouldn’t be a factor in this series, given that both teams clinched their Championship Series on Sunday and have had time to line up their pitching as they prefer.)

Whichever way this series swings, it should offer no shortage of compelling plotlines. It’s the first World Series for Fox broadcaster Joe Davis, who succeeds Joe Buck after 24 years. If it lasts to a seventh game, it would be the latest World Series ever. It’s a rematch of a wild 1980 NLCS. It’s an aged (and ageless) Justin Verlander’s latest bid for World Series redemption. Either Dusty Baker will win his first series as a manager, bolstering his Hall of Fame case, or Dave Dombrowski (who drafted Verlander long ago) will become the first baseball operations leader to win a World Series with three organizations, gilding the lily of his Cooperstown candidacy. The Astros, who’ll undoubtedly hear some trash-can trash talk from Phillies fans, will attempt to win an untainted title, one that might make the cheating their past powerhouses did seem even more misguided. (Then again, on a long enough timescale, almost no franchise is innocent; even if we dismiss the sign-stealing rumors about the Phillies’ last pennant winners, the 1900 Phillies had a sign-stealing system based on binoculars and buzzers.)

This series will also deliver our last glimpse of MLB games with no pitch clock, no shift restrictions, and no limit on pickoff attempts. When Major League Baseball comes back next spring, it will look different. But that’s a prospect to anticipate or dread another day, when there are no World Series contests to distract us. The Phillies are the last team to beat the Astros in a game, and the Astros are the last team to beat the Phillies in a series. We’ll soon learn which of those victories was a sign of celebrations to come.

Thanks to Ryan Nelson and Kenny Jackelen for research assistance.