Stop me if you’ve heard this story before: The Indianapolis Colts’ ballyhooed offseason quarterback acquisition has not lived up to the hype, and Indianapolis is looking to stave off some midseason disappointment. Matt Ryan became the latest Colts quarterback this past offseason, and even as Indy’s offense struggled, it seemed like he’d do the same thing each placeholder before him had done: play for a season and move on.

Colts owner Jim Irsay is officially done with that song and dance. The Colts have elected to bench Ryan in favor of backup quarterback Sam Ehlinger, a 2021 sixth-round selection who presents the most interesting developmental option on the depth chart. The move seems to have come at Irsay’s urging.

There is a lot to read into and take out of the Colts’ quarterback issues: notes on Chris Ballard, Frank Reich, and Matt Ryan alike. But the move to Ehlinger represents the Colts’—or, at the very least, Irsay’s—awareness of a shift in the NFL’s quarterback zeitgeist: The league is moving toward scramblers.

This is related to, but not completely the same as, the league’s move toward mobile quarterbacks in the past decade. After spending the 2000s chasing cerebral, statuesque quarterbacks in the Peyton Manning–Tom Brady mold, the NFL started to find competitive edges with dual-threat quarterbacks such as Cam Newton and Robert Griffin III, and expanded on those edges with Lamar Jackson, Kyler Murray, and others. In 2022, it’s known that the league’s elite quarterbacks—Patrick Mahomes, Josh Allen—can beat you with their arms, no problem. But if you somehow manage to quiet them in the air, they’ll just beat you with their legs instead.

It was with this shift in mind that the Philadelphia Eagles selected Jalen Hurts in the second round of the 2020 NFL draft. A run-first quarterback at Alabama who grew as a passer at Oklahoma, Hurts was considered by NFL.com draft analyst Lance Zierlein to be a developmental player for his “ability to grind out yards on the ground” despite his tendency to “break the pocket when throws are there to be made.” A decade ago, the league wouldn’t have considered the juice worth the squeeze. But the Eagles took him on, and two years later, he’s in the thick of the MVP race as the leader of the league’s last undefeated team.

While Hurts has improved, he is not any different from what he was described as two years ago. Hurts still grinds out tough yards on the ground and still leaves the pocket when there are throws to be made. Through seven weeks, Hurts is third in the league in the percentage of his dropbacks that become scrambles, at 11.2 percent, per TruMedia.

Another quarterback stands out on this list: Daniel Jones. Unlike Hurts, Jones was billed by Zierlein as a potential first-round pick based on “quality mechanics” and the ability to “make pro throws.” Jones’s athleticism and scrambling ability were afterthoughts in evaluations of him, which focused on his pocket passing and game management. And for the first few seasons of his career, Jones was coached and used with those traits in mind. From 2019 to 2021, Jones never scrambled on more than 5.7 percent of his dropbacks; this year he’s at 12.2 percent. He previously attempted a pass on at least 80 percent of his dropbacks; this year, he’s at 71 percent.

Jones’s play style has changed under his new head coach, Brian Daboll, because Daboll understands the value of the scramble. Buffalo passed a ton under Daboll, and with a thrower like Josh Allen, why wouldn’t you? Those throws created scrambling opportunities for Allen, who not only scrambled on more than 7 percent of his dropbacks, but was second in the league in expected points added per scramble. Jones isn’t Allen, but he brings similar athleticism and a similar big body to New York, and Daboll is encouraging his quarterback to scramble to raise the floor of his passing game.

Understanding how scrambles raise the floor of an offense is critical. Mobile quarterbacks are so often described by their ceiling, by the ways their mobility can generate a dual-threat offense in the models of Cam and Lamar. But quarterback scrambling isn’t about ceilings. It’s about floors.

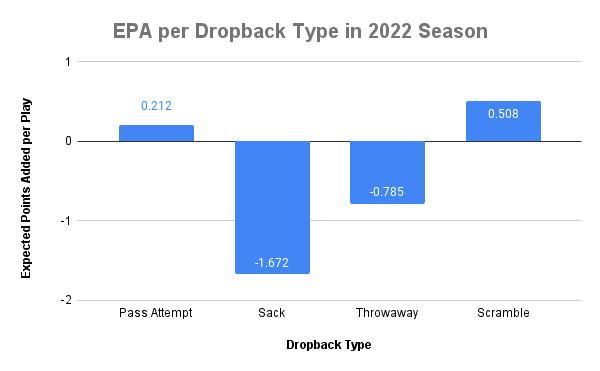

Let’s start with an understanding of what raw data tells us about scrambles. Across all quarterbacks this season, scrambles are producing .508 EPA per play, which is the second-highest mark in any season since 2000. In comparison: The EPA per play of a league-average pass attempt (no spikes, no throwaways) is .212.

By expected points, scrambles are more than twice as valuable as pass attempts.

Put another way: Patrick Mahomes leads the league in EPA per pass attempt at .532. The average quarterback scramble this season is more valuable than any quarterback’s pass attempt, save for Mahomes. And even then, get this: Mahomes’s EPA per pass attempt is .532, and his EPA per scramble is .603. Mahomes is a more valuable scrambler than he is thrower—and he’s the best thrower in the league.

If these numbers seem preposterous, it’s because they are. There is some noise in the data. A disproportionate number of scrambles happen on third downs, when quarterbacks are just trying to get to the sticks—and when they do, they score a huge victory in EPA. But on first and second downs only, the average scramble (.298 EPA/play) is still worth much more than the average pass attempt (.193).

These numbers challenge our understanding of football. When quarterbacks drop back, we want them to throw the football—accurately, of course, and as far down the field as they can get it. Yet, even when we eliminate sacks from our scope (for the time being), it seems more valuable for our offense that the quarterback tuck and run on every dropback than choose to throw the football. How? Why?

This sensation is not dissimilar to the discourse around play-action passes. By EPA per play, play-action passes are far better than standard dropback passes. Like scrambles, play-action numbers are slightly skewed by the context of which down-and-distances offenses run them. But play-action passes present the initial look of a run, fooling the defense and making passing easier; don’t quarterback scrambles initially present pass, fool the defense, and suddenly become an easier running play?

They do—and, like play-action passes, there’s probably a point of saturation at which that value starts to diminish. Take Bears quarterback Justin Fields, the current league leader in scramble rate with a scramble on a whopping 17.7 percent of his dropbacks—that’s nearly one out of every five dropbacks! Fields is one of the most physically gifted runners in the league at any position, let alone quarterback—yet by EPA per scramble, he’s ninth, behind players including Geno Smith, Joe Burrow, and Derek Carr. Scramble too much, and defenses won’t fear your passing game once they get pressure or take away your first read. They know what you’re going to do next.

But the full value of scrambles isn’t even captured by EPA. EPA looks at the expectation that an offense will score given a certain down-and-distance (for example, first-and-10 from the 50), and then compares it to the new expectation that an offense will score given a new down-and-distance (second-and-1 from the 41 after a 9-yard gain). It does not consider alternatives. A 9-yard run by a running back on that first-and-10 from the 50 adds the same expected points as a 9-yard catch by a receiver or a 9-yard scramble by the quarterback.

This is where we must consider what a scramble replaces—what could have otherwise happened in a play on which a quarterback scrambled. While scrambles can happen on unpressured plays, we expect to see a quarterback scramble as a response to pressure in the pocket. Across the NFL this season, scrambles happen three times as often when the quarterback is pressured (7.7 percent) than when he isn’t (2.8 percent). Throwaways become almost eight times as likely, going from 1.3 percent to 9.7 percent. Sacks, unsurprisingly, occur almost exclusively on pressured plays. This, in a nutshell, is the anecdotal value of pressure: It often forces quarterbacks to do something other than throwing the football—and, if they do throw the football, they throw it poorly, as pressure increases inaccuracy and creates interceptions.

But one of the things that pressure invites quarterbacks to do—scramble—is not like the others! It is dramatically more valuable than the others. Pressure is still a worthy pursuit for defenses because of the many negative plays it creates, but if a quarterback can escape that pressure, he can punish it with a scramble.

This is where quarterback scrambling raises the floor of an offense. A quarterback who can scramble when pressured is not just creating a positive play, but also erasing a hugely negative play: a sack. Just one sack on a drive makes it three times less likely that that drive will end in a touchdown than when compared with a sack-less drive—and accordingly, the ability to avoid sacks is perhaps the most valuable skill a quarterback can have. We notice it less often than most quarterback highlights—the heroic third-and-long conversions or fourth-and-goal connections in the end zone—but in terms of momentum-shifting, scale-tipping plays, the quarterback scramble to escape pressure and avoid a sack is among the greats. It just happens too often and too mundanely for us to notice.

Consider a quarterback with little to no scramble ability at all. Quarterbacks like Tom Brady, Jimmy Garoppolo, Davis Mills, and Matt Ryan. When they are pressured, they are almost certainly not going to try to break the pocket. Instead, they’ll throw the ball away or take a sack—or attempt a pass, but one that is far more likely to be inaccurate. No matter what, it’s a win for the defense, and we can see it in the performance of these stationary passers. With pressure, Brady falls from 17th in EPA per dropback to 31st; Jimmy from third to 32nd. (Houston QB Davis Mills weirdly goes from 33rd in EPA per dropback without pressure to 12th with pressure. Don’t ask me what’s going on there. I have no idea.) But most importantly for our conversation today: Matt Ryan falls from 11th to 33rd.

There are a billion reasons why the Colts offense looks so bad—some Ryan’s fault, some not. But regardless of the context, the 37-year-old pocket passer has not been able to handle the pressure surrendered by the Colts’ dreadful offensive line this season. Pressured on 33.6 percent of his dropbacks, Ryan was sacked 21.8 percent of the time when pressured, a bottom-10 figure among passers this season. At the Colts’ increased pace of play and pass reliance, that accounts for 110 pressured dropbacks (second only to Justin Herbert) and 24 sacks taken (second only to Justin Fields).

The Colts’ pass protection issues are not going away. After playing musical chairs with veteran Matt Pryor, rookie Bernhard Raimann, flipping Braden Smith across a couple of positions, and benching Danny Pinter, Indy has yet to find a working combination up front. They need a quarterback who can respond to pressure.

That is Sam Ehlinger: a 6-foot-1, 222-pound second-year player with 554 rushing attempts, 1,903 rushing yards, and 33 rushing touchdowns to his name at the University of Texas. Ehlinger is not as good of a passer as Matt Ryan is, even at this point in Ryan’s career. Ehlinger also isn’t as good of a runner as Jalen Hurts or even Daniel Jones. But he is a runner. He’s probably going to take some dumb sacks, sure—but he’s also going to turn some of the sacks Ryan would take into 5-yard runs. That’s turning a second-and-17 into a second-and-5. That might save the Colts offense.

It probably won’t. Ehlinger’s not a very good quarterback, so the loss elsewhere—in accurate passes to Michael Pittman Jr. and smart dump-offs to Nyheim Hines and pre-snap adjustments for everyone—may be too great to overcome. But that makes Ehlinger a lovely test balloon for the NFL’s ever-increasing interest in mobile quarterbacks. Just how bad of a passer can we put out there, so long as his legs and willingness to scramble keep him afloat? Will his legs still raise the floor?

If Ehlinger proves effective, expect more and more teams to continue grabbing mobile quarterbacks with Day 2 and Day 3 picks. But an updated understanding of quarterback scrambling doesn’t just change our draft and player evaluation process. It changes how the league coaches quarterbacks. Instead of insisting young passers do their best Peyton Manning impressions by studying and setting protections against myriad defensive blitz looks, or pull their best Tom Brady and always find the extra sliver of space in the pocket to avoid the sack and get rid of the football, teams will start coaching their quarterbacks to scramble. If you find space, take it. If it’s going to be a positive play, go now. If you get out of the pocket, tuck and go. It’s going to change the way offensive lines block and the way receivers behave on their scramble drills. The quarterback scramble is one of the most valuable plays in football, and the Colts are joining the swell of teams trying to figure out just how much value they can get out of it.