2022 has been a season of shifts in the NFL landscape. The Los Angeles Rams won the Super Bowl just eight months ago and now look dreadful; the Tampa Bay Buccaneers won the Super Bowl in 2021 and don’t look too much better. The Green Bay Packers also belong in that bucket of NFC disappointments: They’re 3-2, with their past two Sundays consisting of an overtime win over the Bailey Zappe–led New England Patriots and a London loss to the Daniel Jones–led New York Giants. Things aren’t bleak in Green Bay, but they’re certainly a little cloudy.

The first weeks of the season are often bumpy and uncertain—Rodgers famously told fans to R-E-L-A-X after a 1-2 start in 2014, turning that season into a 12-4 finish and a division title. Even last year, the Packers chased their Week 1 stinker against the Saints with seven straight victories en route to another division title and an(other) MVP award for Rodgers.

But this year feels a little different. There are issues on both sides of the ball, some relating to the team’s schemes, and some to its players. And having a lot of issues makes it hard to believe the Packers can get right back to NFC contention the way they have before.

Here’s what’s wrong in Green Bay, and what I think has to be done to fix it.

Defense: We have the players, but we don’t have the scheme

The Packers have seven first-round picks on the defensive side of the ball: Rashan Gary, Devonte Wyatt, Kenny Clark, Quay Walker, Jaire Alexander, Eric Stokes, and Darnell Savage. These aren’t old, washed, transplant first-rounders. Each was selected by the Packers, and the oldest is Clark at 27. This list doesn’t even include big-contract players like Preston Smith, Adrian Amos, and De’Vondre Campbell.

The Packers defense has talent, and when a talented defense is playing poorly, it falls on the defensive coordinator.

Joe Barry is in his second season coordinating the Packers defense, but he brings plenty of experience: Previously, he was the defensive coordinator in Detroit and Washington. That experience wasn’t great, though: Barry’s defenses were below average in Washington and cellar-dwelling in Detroit. In his first season with the Packers, Barry’s defense was 22nd by DVOA and 19th by expected points added per play allowed. Five games into his second season, the Packers defense is 23rd by DVOA and 16th by EPA per play allowed. So, better? Maybe? But still bad.

Barry hasn’t put a good defense on the field in his six seasons as a coordinator—so why does he currently have the Packers job? Before coming to Green Bay, Barry was with the Rams, coaching linebackers under coordinator Wade Phillips and, later, Brandon Staley. The immediate success of Staley’s defense caught the league’s attention, and the brain drain began: In the past two offseasons, Aubrey Pleasant, Ejiro Evero, and Barry have all been hired off the Rams’ staff to bigger defensive coaching jobs elsewhere.

Barry has brought plenty of the broad strokes of Staley’s defense to Green Bay. The Packers present light boxes on 65 percent of their defensive snaps, which is eighth in the league, and a two-high shell on 75 percent, which is third in the league—the 2020 Rams were at 78 percent and 79 percent on the same metrics, respectively. On film, we see much of the same stuff being run by all branches of the Vic Fangio tree: bear fronts, split safeties, zone coverages.

How can a team with this much talent, running a system that has largely succeeded in the NFL, be bad? It’s because they’re poorly coached. Throw on any Packers film, and you’ll see players put into disadvantageous spots. The back seven regularly fails to exchange routes in coverage, as players miscommunicate on rules and responsibilities, leaving open receivers streaking across the field. After Week 1, it seemed like it was just an issue of Justin Jefferson’s talent and the trickiness of Minnesota’s designs—but since then, the Packers still haven’t been able to deal with common route combinations.

Crossing routes especially have caused the Packers issues. In zone coverage, Green Bay has allowed a 134.3 passer rating to opposing quarterbacks on plays with at least one crossing route—only the Steelers are worse. Put the Packers in man coverage, and they’re the sixth best—but there are only nine snaps in that sample.

That the Packers are primarily a zone team is not surprising, considering Barry’s influences. From their presnap, split-safety looks, the Packers either play quarters (19.1 percent of the time) with both safeties sticking to their half of the field, or rotate one safety into the box and the other to center field and play Cover 3 (44.6 percent). This maps onto Staley’s defense when Barry was there (the Rams ran quarters 25 percent of the time and Cover 3 for 35 percent of the snaps).

But the fact that the Packers don’t play much man coverage is surprising relative to their defensive backfield’s talent level. With Alexander, Stokes, Douglas, Amos, and Savage, the options are available for stifling man coverage against a variety of receiving corps. Douglas can bounce outside for big receivers; Alexander can play over the slot. But Barry does not tap into that talented secondary save for clear passing downs—the Packers roll out man coverage 15 percent of the time on first and second down, which is the ninth-lowest figure in the league; on third downs of at least 5 yards, that number doubles.

The Packers’ early-down/late-down splits are perhaps the most clear illustration of their defensive issues. The table below shows how often the defense gets a successful play—a play with negative expected points added for the offense—split by down. The Packers are a bottom-quartile team on first and second down, and then the moment they get to third down, they become the league’s best defense.

Packers defense by down

We can interrogate these numbers a little further to understand why the Packers look so good on third downs. The main reason is because they aren’t forcing them. With the league’s second-worst success rate on second down, the Packers are so frequently giving up first downs before even getting to third down that they’ve faced only 53 total third downs this year—that’s the second-lowest number in the league. And when they do face third downs, it’s often with a far way to go—third-down offenses facing the Packers need an average of 7.55 yards to gain, the fifth-highest number among NFL defenses—because the only third downs the Packers are forcing come with negative plays for the offense on early downs. They don’t get teams into third-and-3 or third-and-4—they either get them into third-and-8, or they don’t get them into third down at all.

But the Packers’ third-down performance is also a product of their changing fronts. The Packers lead the league in blitz rate on first and second down at 43.2 percent—but they aren’t really blitzing. They’re sending five-plus rushers because of how often they line up in five-down fronts. With three interior defensive linemen flanked by big outside linebackers in Rashan Gary and Preston Smith, the Packers don’t really have anyone they want to drop in coverage off the line (remember how funny it was to watch Smith drop into coverage across from Justin Jefferson?). So they tend to just rush all five.

But that’s … not actually a blitz. The Packers don’t have a defensive back with more than four pass-rushing snaps this season. At linebacker, Smith and Gary are rushing on over 90 percent of their snaps, while the true off-ball linebackers, Quay Walker and De’Vondre Campbell, are rushing on 15.6 percent and 3.9 percent of their snaps, respectively. Campbell’s number is the sixth lowest among NFL linebackers this year.

On early downs, the Packers line up four or five rushers, and send those four or five dudes. They don’t run many stunts or twists, or change where the rushers are coming from. The Packers are one of only two teams with no snaps of only three rushers, and their four total snaps of six-plus rushers is one of the league’s lowest numbers. Behind those rushers, they play zone coverage—either Cover 3 or quarters. Then they hope that you’ll stumble your way into a third down. When you eventually do, it’s usually a long one. Their pass rushers can tee off, they can play stickier coverage, and they can get off the field.

This is an unacceptably passive, straightforward, and predictable way to play defense. Opposing offenses know what they’re getting from the Packers, and that makes execution easier. Their weak points (defensive tackles not named Kenny Clark; Gary in run defense; Walker in zone conflict) are easier to exploit when they are never relocated or concealed in any way. The Packers are static, and their talented unit underperforms accordingly.

What’s the solution here? The solution is to grow up. Get creative. Assume the other team also has talent and realize that you have to adjust, week to week, half to half, drive to drive if you want to survive in the NFL. Staley’s Rams played tons of quarter-quarter-half to change up zone coverage tendencies and get a safety dropping on the ever-dangerous crossing route—the Packers aren’t doing that. Other Fangio-inspired teams, like the Eagles under Jonathan Gannon, are dropping one of their outside linebackers in their bear fronts to create confusion—the Packers aren’t doing that. The Broncos under Ejiro Evero are gaming the front—the Packers aren’t.

Green Bay’s defensive coaching staff is failing its players. They can change that. They have to fix the execution issues within the defense they’re running, or change what they’re running altogether—ideally, both! These changes are possible and achievable, but they require humility—an admission that what’s currently happening isn’t working. That can be rare among NFL coaches. But the changes are possible and achievable.

So the Packers’ defensive changes are within their grasp. The same may not be true for the Packers offense

Offense: We have the scheme, but we don’t have the players

Green Bay’s offensive struggles do not seem as dire as the defense’s. They are eighth by offensive DVOA and 14th by EPA per play. Not incredible, but above average, and far from the team’s biggest problems. But there are issues under the surface.

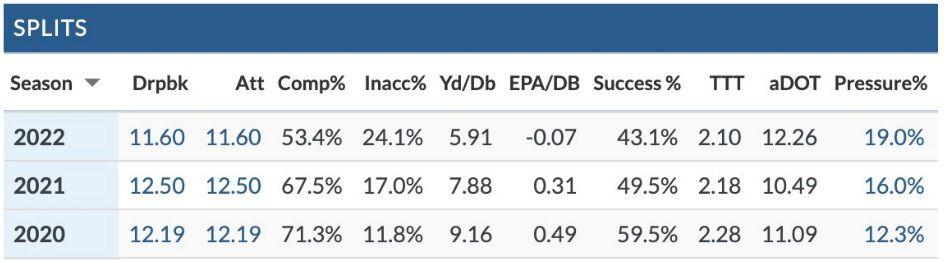

The first issue is that the field is shrinking. The Ringer’s Steven Ruiz pulled these numbers (via TruMedia) on Rodgers’s passing performance beyond the line of scrimmage and outside of the numbers.

Rodgers’s completion percentage has plummeted while his inaccurate pass rate has leapt—EPA per dropback and success rate both show that his efficiency to these areas of the field is way down.

This falling off shouldn’t come as a surprise. Not only is Davante Adams gone—and Adams was perhaps the league’s most dominant receiver on vertical routes and back-shoulder balls—but field-stretcher Marquez Valdes-Scantling is no longer taking snaps along the outside and challenging defensive backs one-on-one. The dropoff in wide receiver play contributes to the falling off of the numbers, as an outside ball to Randall Cobb or Allen Lazard is simply less likely to be completed or valuable than one to Adams. This was the expected tailing off of the Packers offense, and while I’m sure Green Bay’s offensive coaching staff believed they could work around it, they’ve failed to do so.

One of the ways the Packers wanted to create a post-Davante offense was with two-back sets. By putting Aaron Jones and AJ Dillon on the field at the same time, the Packers believed they could force defenses into base sets, run RPOs with the backs motioning out of the backfield, and find a downfield passing game off of play-action. Rodgers predicted in the offseason that both Dillon and Jones could become 50-catch running backs.

This has not even remotely happened. The Packers have averaged 4.09 yards per play and a 37.8 percent offensive success rate in two-back sets; with one or fewer backs on the field, they’re at 5.92 yards per play and 46.0 percent success rate. Perhaps most notably, their explosive play rate sits at 4.4 percent in two-back sets; with one or fewer backs, they’re triple that number at 13.2 percent. After using two-back personnel on at least 10 snaps through the last three weeks, the Packers only used it on three snaps in their game against the Giants. And in Dillon and Jones’s 50-plus target race, Dillon has fallen off. His participation in the offense has decreased overall, and his participation in the passing offense has bottomed out.

Dillon was an interesting pick in 2020, when the Packers drafted him near the end of the second round. You remember: When Rodgers publicly asked for a receiver, and instead got a first-round quarterback, a second-round running back, and a third-round FB/TE? That quarterback (Jordan Love) obviously hasn’t brought Rodgers and the offense any value; Josiah Deguara, the FB/TE, has 30 career catches. Dillon was always going to have difficulty providing value while backing up Aaron Jones, but the offensive staff carved out a substantial role for him this year, and he’s failed to deliver in it.

That leaves the Packers offense in a tricky spot. With two-back personnel scrapped, the Packers are now stuck throwing all of their short-game RPOs—many of which develop behind the line of scrimmage—to players who are not as dangerous with the ball in their hands. When a swing route 4 yards behind the line of scrimmage went to Dillon, or a quick screen went to Adams, it felt dangerous because the ballcarrier was dangerous. Now? The ball is going to Robert Tonyan, Romeo Doubs, Christian Watson, and Lazard. The only players generating positive EPA on targets behind the line of scrimmage for the Packers are Jones and Tonyan.

Yet Rodgers throws behind the line of scrimmage more than almost any other quarterback (and has been since head coach Matt LaFleur came to town). It worked when the field was wider and longer—when defenses were worried about the deep outside throws to Adams or MVS. That concern isn’t there without those players, and as a result, the field is shrinking.

Rodgers feels it shrinking, and he wants to fight it. That’s why you start to get from Rodgers these desperation heaves—downfield launches into routes that have not separated at all, with the hope of ripping off a chunk gain, winning a one-on-one, forcing a defense to fear Lazard or Watson or Doubs. As the Giants game spiraled late for the Packers, Rodgers began hunting the deep shot, the killing blow that would cement a Packers win—he just couldn’t find it. And that’s been an issue for him all year: As Cale Clinton detailed for Football Outsiders, this is the worst deep passing season Rodgers has had since at least 2018.

This is a worryingly familiar sight for Packers fans, as it’s not dissimilar to what Rodgers used to do under former head coach Mike McCarthy at the end of that long and fraught relationship. He would play with frustration, feeling like the offense wasn’t doing enough for him; that he needed to play like a hero in order for this all to work. But back then, it was about designs—McCarthy failing to maximize his quarterback and weapons. Now, the designs are sound—LaFleur knows what buttons to press. It’s about talent. The Packers lost their two best receivers and haven’t been able to replace them. The passing game is suffering.

This is harder to solve. Scheme can do some of the work—the Packers’ under-center, play-action passing game is pretty good, and they can use it more as they transition back to being a one-back offense that features Jones and occasionally rotates in Dillon. By using Tonyan and Lazard as standup receivers (with Tyler Davis as the true tight end), they can model themselves after the 2017 Rams offense that LaFleur coordinated, living in 11 personnel and finding YAC opportunities off of play-action over the middle of the field.

But that requires Rodgers’s acquiescence. It takes decision-making and progressions out of his hands. He’d have to become robotic, a cog in the machine, a point-and-shoot quarterback.

I’m not convinced that Rodgers wants to be that. Back-to-back MVPs typically don’t like having their role in the offense diminished, especially when they are as … enthusiastic about having influence over the team as Rodgers has been over the past few seasons. And Rodgers doesn’t deserve to be minimized! He isn’t the problem. He’s not playing his best ball, but he’s frustrated with the poor weapons he’s been provided, and understandably so.

That’s what makes this issue harder to solve. Offense was so easy for the Packers when Adams was in town. They’d run their little RPO games, get the ball where the defense didn’t have numbers, and walk it down the field—when they got behind the sticks, they’d find a way to open Adams up with all the space available to them on the field, and get a first down. Now, everything’s tight. The field is condensed. The receivers don’t get open as easily or as often, and don’t do as much when they are open. The margin for error around them has decreased: Rodgers has to be better, always finding the right read and trusting the scheme; pass protection has to hold up, even as the line continues to be shuffled. Put simply, offense is just tougher now in Green Bay.

Green Bay’s diagnosis is easy. The prognosis isn’t. It’s difficult to see how everything that’s bad gets better—but Rodgers is a very, very good quarterback, and LaFleur is a very, very good coach. An embarrassing loss to the Giants on a weird day in London can certainly serve as a kick in the pants for the underperforming players, and a 3-2 start is no big hole to climb out of, especially with soft opponents like the Jets and Commanders offering get-right opportunities in the next two weeks. But after Washington comes Buffalo, Detroit, Dallas, Tennessee, and Philadelphia. The clock is ticking, and there’s plenty of work to be done on both sides of the ball. If Green Bay’s gonna get right, it has to do it fast.