Here’s a secret about the AL MVP debate surrounding Aaron Judge and Shohei Ohtani: You and I don’t have to have it. The only people who have to choose sides and elevate one awe-inspiring season over the other are the 30 voters who’ll submit their ballots before the first pitch of the postseason this Friday. Their decision, which won’t be revealed until November, doesn’t change the astounding sights and stats that we’ve already seen for ourselves, and the rest of us needn’t abide by it. Nor need we burnish one superstar at the other’s expense. Great Pyramid of Giza, or Mausoleum at Halicarnassus? Both great tombs. Colossus of Rhodes, or Statue of Zeus at Olympia? Two impressive sculptures. Other ancient structures may have been—in MVP parlance—“in the conversation,” but when you’re a Wonder of the World, you’re above such squabbles. The Seven Wonders weren’t ranked. (Or, if they were, the hot-take tablets and scrolls were lost to history too.)

There’s no harm in having the debate for fun, of course, or as an intellectual inquiry into how we determine value in baseball, but often the topic turns contentious and territorial, a reason to tear down instead of celebrate. Judge and Ohtani aren’t going head-to-head in the playoffs, and they aren’t competing for the same roster spot. They don’t play the same positions, they aren’t division rivals, and they aren’t reaching free agency at the same time. The fact that they happened to play in the same league, and that their remarkable campaigns coincided, doesn’t force us to throw in with Team Ohtani or Team Judge any more than it obligates us to wring our hands, lose sleep, or send impassioned tweets about whether, say, Daulton Varsho was more valuable than Willy Adames. Who wouldn’t want to suit up with either Team Ohtani or Team Judge, or preferably both? The two titans of 2022 performed sports miracles that no one else came close to approximating. Either would run away with the award if not for the other. If anything, the MVP outcome means less this season, from a legacy perspective, than it normally would. In this race, neither the winner’s nor the runner-up’s feats will be forgotten.

This, then, is a Judge and Ohtani appreciation post. It’s not about which one was better or more valuable, whatever “valuable” means. You can sort by WAR without my help—Judge finished ahead, by one to two wins depending on the flavor, and there isn’t much to support the contention that the framework for the metric undervalues Ohtani by nearly enough to make up the shortfall. Single-season WAR doesn’t measure true talent, and it doesn’t necessarily reflect spectacle, excitement, or degree of difficulty—none of which must be admissible in the court of MVP opinion. Whatever WAR says, though, a nonvoter isn’t bound to pit the two against each other. That’s right: I’m taking a strong, divisive stance that both players are praiseworthy. (Cue the Eric Andre GIF.) Free your mind from the tyranny of first and second, the binary of best and second-best, the banality of victor and also-ran. For the following reasons, these seasons are too singular, sensational, and historically significant for only one party to “win.” Everyone who watched them won already.

Let’s start with Judge. (Relax—I’m going in alphabetical order.) Judge, who turned 30 in April, hit 62 homers, an American League record. (It’s not and never should be the overall record, but if you want to call it the highest homer total attained by someone not associated with steroids, sure, that’s true too.) Most record-setting seasons come from a confluence of extraordinary talent and conditions conducive to outlier years. Judge, a giant who’s unreasonably agile for his size, checks the first box, but the context in which he hit 62 wasn’t especially inflationary compared to past legendary dinger years, even putting PEDs aside.

The ball, while still fairly lively by historical standards, is deader than it has been in several seasons—and possibly deader than it was when Mark McGwire, Sammy Sosa, and Barry Bonds roamed the field. According to Baseball-Reference, Judge’s performance this season, ported to a neutral park during the peak home-run-rate years of 2017 or 2019, would have yielded an extra four or five homers, respectively; and on a level league/park playing field, the distance between Judge’s homer high and those of Bonds, McGwire, and Sosa would shrink. Likewise, Judge’s stats weren’t inflated by segregation, expansion, or in Chris Woodward’s words, a “little league park”: Per Statcast, Yankee Stadium played pretty neutral for right-handed home runs, and Judge’s “expected” home run total was 61.9. (Granted, that gap is an important 0.1.) Judge’s power plays anywhere; 32 of his homers came on the road. And that was without the benefit of playing away games in Baltimore in the bandbox Camden Yards used to be. Oriole Park went from the best home-run park for right-handed hitters last year to one of the worst in 2022, and although Judge hit five taters there anyway, he would have had six if not for the fence move.

MLB’s caliber of competition has never been better, and it’s harder than ever for stars to stand out. Even so, Judge paced the field by 16 homers and led his league by 22, margins unmatched for 90 years or more. Yet focusing on his homers to the exclusion of all else would do Judge a disservice: WAR-wise, he easily outstripped any previous 60-plus-homer season save for Babe Ruth’s 1927 and Bonds’s 2001. His 207 wRC+ was the best since Bonds in 2004, and the best of any qualified post-integration season except for Bonds from 2001 to 2004 and Ted Williams and Mickey Mantle in 1957 (when Williams’s team still wasn’t integrated). He led the league (if not the majors) in every notable offensive category but batting average, in which he trailed the Twins’ Triple Crown thwarter Luis Arraez by five points. He even stole 16 bases in 19 attempts.

He did all that while playing plus defense—even, by some metrics, in center field, where only one previous player his height, 1960s journeyman Walt Bond, had ever stood. He did all that while regularly batting leadoff, almost a brand-new role for him. And he did all that while weathering intense scrutiny, seeing the fewest pitches in the zone over the last two weeks of the season, and buoying the rest of the Yankees lineup, which sagged so severely that it ran the risk of squandering a massive early lead in the division. (The Yankees’ collective OPS sank by 58 points in the second half, even though Judge—who entered the All-Star break with 33 bombs—boosted his by 303 points, posting the best second-half figure relative to the league of any hitter other than Ruth, Williams, and Bonds.) Oh, and he did all that after reportedly turning down an eight-year, $230.5 million extension offer from the Yankees, a bold decision that’s probably about to pay off.

Judge—who stayed healthy, hit the ball harder than ever, and both launched fly balls and pulled his flies more often—didn’t just have one of the most extraordinary home run seasons ever; he had one of the most superlative all-around offensive seasons. Hell, we can cut the “offensive”: Since Mantle’s ’56 Triple Crown year, the only players to top Judge’s 11.4 FanGraphs WAR were Bonds and Pedro Martínez.

Now, Ohtani’s turn. In March, I examined whether Ohtani could be even better than he was in his unanimous MVP campaign. I concluded that though the odds are against any reigning MVP improving—you have to stay healthy to win one and usually have a little luck on your side—there was ample evidence that Ohtani’s best could be ahead of him. That turned out to be true—and, almost scarily, I could probably say the same next spring.

One reason Ohtani’s WARs went up is that he simply played more, hard as it was to surpass last season’s durable baseline. A year ago, I marveled that Ohtani had compiled 1,172 combined plate appearances and batters faced, the highest total this century. Thanks to the Ohtani rule, the universal DH, and his improved durability on the mound, he far surpassed that sum this season, batting 666 times and facing 660 batters for a sum of 1,326. That’s the most since Steve Carlton’s 1,339 in 1980, and 440 more than the next-most-prolific player this season (NL Cy Young favorite Sandy Alcantara, at 886). He smashed his own record for the most pitches thrown and faced in a season since the advent of comprehensive pitch-count data in 1988, and he became the first modern-era player to amass 600 plate appearances and 600 batters faced, to qualify for both the batting title and the ERA title, and to lead his team in plate appearances and innings pitched. Granted, he didn’t play defense most days. What a slacker.

There’s a marvelous symmetry to Ohtani’s stats: almost identical counts of PA and BF; the seventh-hardest batted balls and the seventh-hardest fastballs thrown; the lowest career OPS allowed since World War II with runners in scoring position, and the highest career slugging percentage produced. However, the two sides of Ohtani aren’t in perfect balance. Last year, Ohtani accrued more of his value as a hitter than as a pitcher. This year, the hierarchy of his two-way contributions flipped.

Ohtani remained potent at the plate, lifting 34 homers and tying for 15th among qualified bats in wRC+, but most of his offensive stats slipped slightly: He made more contact, but he hit the ball less hard, walked less often, and struggled as a base stealer (though he retained the title of fastest runner from home to first). However, his pitching more than made up for those dips. (Side note: Ohtani has long expressed his preference for hitting on the days when he pitches, but he hasn’t really raked in that scenario. Since the start of last season, he’s compiled a .944 OPS in 1,120 plate appearances on non-pitching days and a .762 OPS in 185 plate appearances on pitching days. This season, the disparity was 175 points, up from 166 last year, but his .730 OPS on pitching days still surpassed the .711 league average at DH.)

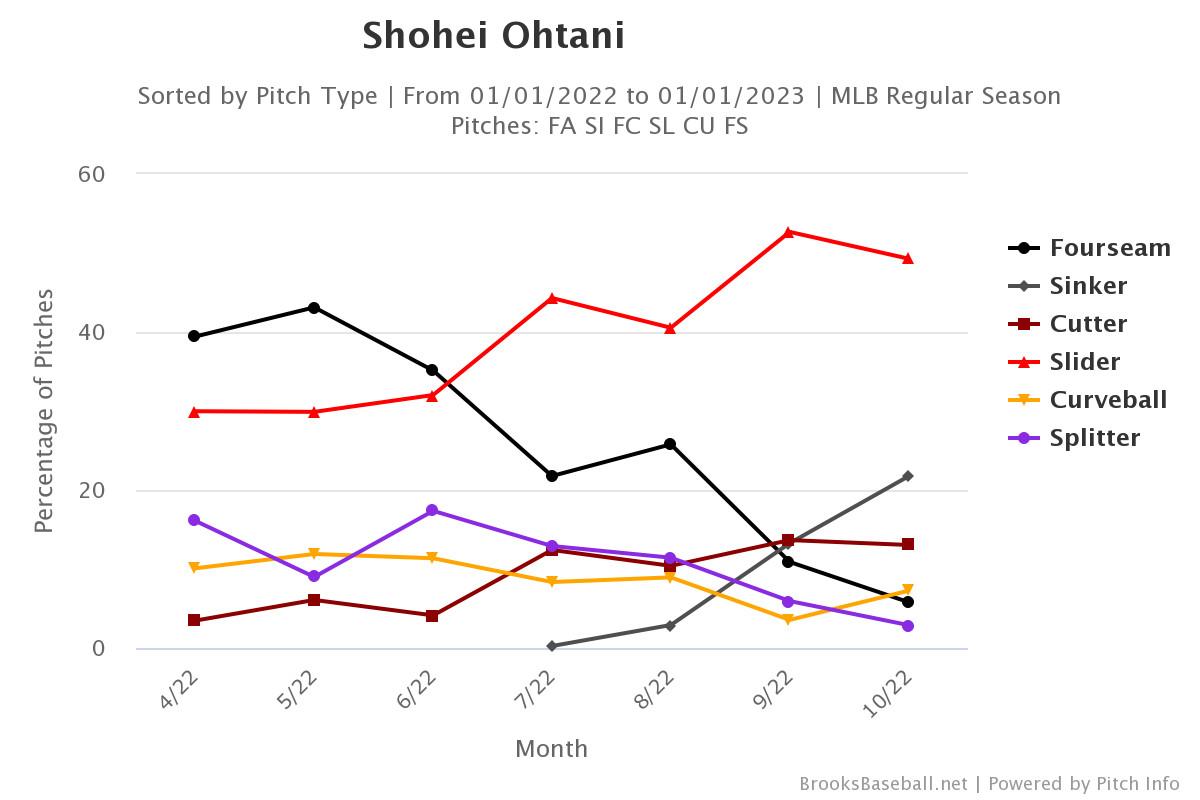

Ohtani’s pitching picked up over the course of last season, as the rust from his lengthy, injury-related layoff wore off. But he reached a new level this year, for a few reasons. For one thing, he threw far harder, on average, than he did last year—less because his max speeds increased than because he embraced more of a max-effort (or at least moderate-effort) approach, in which he was more likely to throw toward the top of his speed range regularly, rather than hold his highest velo in reserve for big moments. For another, he’s continued to overhaul his repertoire and pitch usage on the fly, in an almost shockingly drastic and successful manner. Look at how his pitch mix evolved from month to month this season:

Ohtani debuted a harder, nastier slider at the start of this season, and he went to it more and more as the season wore on. Last season, he threw sliders about 22 percent of the time; this September, he threw them more than half of the time. As of June, he said he had no sinker, but months later, he’d added one, and guess what: It’s good. The rise of his devastating slider-sinker combo has enabled him to throw far fewer four-seamers (one of his least effective pitches), and he still has a splitter, cutter, and curve. According to analyst Cameron Grove’s stuff- and command-based pitching model, Ohtani (along with Dustin May, in a much smaller sample) is the only pitcher who has five above-average pitches and two that grade out at 65 or higher on the 20-80 scouting scale. He’s also the only pitcher who has five pitches with command-independent “stuff” grades of 60 or higher.

It’s a filthy mix, and it shows. Among all pitchers with at least 100 innings pitched this season, Ohtani ranked third in strikeout rate, second in strikeout minus walk rate, and third in park-adjusted FIP. In his last 19 starts of the season—a span of 118 2/3 innings, dating back to June 9—he recorded a 1.67 ERA and a 2.03 FIP, with 154 strikeouts and only 33 walks. Over that roughly four-month period, he tied for the major league lead in FanGraphs pitching WAR. He’s already ramped up from pitching every sixth game to pitching every sixth day, regardless of off days; it’s possible that he’ll pitch in a five-man rotation next year. Even if he stays on the same schedule, the prospect of a full season of a slider-rific, sinker-equipped Ohtani is intoxicating to contemplate, especially—to get even greedier—if his bat rebounds.

In addition to being a cinch for top two in MVP voting, Ohtani should be a shoo-in for the top five in Cy Young voting, if not the top three. (He’s first, second, and third, respectively, in the AL in pitching WARP, bWAR, and fWAR.) In all of major league history, only Bullet Rogan can rival Ohtani’s two-way dominance, and Rogan didn’t have the opportunity to play as many league games in a season. We’re way past Ruth comps at this point; the 28-year-old Ohtani is blazing a two-way trail that may never be trod again. In that sense, he makes Judge seem almost conventional, albeit no less valuable. It’s easier to picture Ohtani having a Judge-like season than the other way around, not that we should pencil in 62 for Ohtani anytime soon.

Quite a few MVPs have upped their WAR total in the season after their win without taking home the hardware again. Only three times in history, however, has a non-full-time pitcher posted a Baseball-Reference WAR as high as Ohtani’s this season and lost the MVP award to a hitter who had an even higher WAR: Williams in ’57 (finished second to Mantle), Sosa in 2001 (finished second to Bonds), and Mike Trout in 2018 (finished second to Mookie Betts). Ohtani will likely join that group, but settling for second wouldn’t make his building on an impossible season any less astonishing. The dream of two-way Ohtani came true last year, and we still haven’t had to wake up from it.

This season’s stretch run lacked suspense in the standings, but the exploits of Judge and Ohtani compensated for the flaws in the pennant race. On the individual player level, they, along with Albert Pujols, were the stories of the season. They captured our attention, our imaginations, and (in the ever-endearing Ohtani’s case, certainly) our hearts. And between the two of them, they showed us every way one can excel at a special sport—in the same season and sometimes the same inning. There’s no debate about that.

Thanks to Lucas Apostoleris, Cameron Grove, and Kenny Jackelen for research assistance.