The Philadelphia Eagles are the last undefeated team in the NFL. It feels like it should be easy to point at something on the league’s only undefeated squad and go “Well, that’s why.” But for the Eagles, it isn’t.

Look just at the season opener against the Lions, and the answer would be A.J. Brown. The team traded for the star receiver after struggling to get their wideouts involved in the passing game last year, and Brown dominated in his Philadelphia debut: 10 catches for 155 yards, which set up four rushing touchdowns from four different players en route to a 38-35 victory.

The next couple of weeks, the defense was the answer. In Week 2, the Eagles grabbed three picks; the week after that, they tallied nine sacks, allowing 7 and 8 points, respectively. During this stretch Brown grew quieter as Dallas Goedert and DeVonta Smith got louder. The running game kept on chugging behind the league’s best offensive line, which features stars in Jordan Mailata, Jason Kelce, and Lane Johnson, and an ascending talent in Landon Dickerson. Head coach Nick Sirianni is making all of the right decisions as a new offensive player sets a career-best mark every week: Smith in Week 3, Miles Sanders in Week 4. In short, everything is working.

Somewhere in all of this is third-year quarterback Jalen Hurts: a former second-round pick, the insurance plan to Carson Wentz, the perceived holdover for a new quarterback to be acquired at a later date. Nobody told Hurts that he was just a bridge. Hurts ranks fifth in the league in EPA per dropback and eighth in completion percentage over expectation, captaining a better passing attack than anyone thought possible with a run-first quarterback at the helm—oh, and that run-first quarterback has four rushing touchdowns, which is third-best in the NFL, and over 200 rushing yards in the league’s sixth-best rushing attack by EPA per play.

At first brush, Hurts looks like a cog in the Eagles machine. He isn’t a big-money player or a high draft pick, and as a limited passer, we don’t expect him to be a quarterback that elevates the passing game overall—just a piece of the puzzle that executes his portion. But Hurts is unique, and the Eagles offense is unique around him. There isn’t an NFL offense that looks like the Eagles’ does right now, and that’s because the Eagles aren’t running an NFL offense—they’re running a college one.

The first hint that the Eagles are running a college offense is in their reliance on RPOs—at a 19 percent clip, only the Chiefs are running RPOs (run-pass options) more frequently. While the Chiefs have a varied passing attack and use the RPO game to buttress their poor rushing attack, the Eagles lean on the RPO to do the opposite. Their RPO game is the bread and butter of their passing approach, simplifying Hurts’s reads and ensuring he gets the ball to his playmakers.

Take one of the most common, basic, white-bread RPOs the world has ever seen: glance. This RPO, like most post-snap RPOs, asks the quarterback to read and react to one defender: the playside linebacker (here, Devin Lloyd). The glance route is an in-breaking route that’s too deep to be a slant but too shallow to be a post, and it breaks right behind that linebacker. If the linebacker steps forward to fit the run, as Lloyd does here, Hurts will throw the ball. If Lloyd sinks into his zone, Hurts will give the ball to the back, who should pick up a healthy gain with the numbers advantage in the box.

I cannot stress how simple and easy of a play this is. I’d wager every single college team in the country has this somewhere in their playbook. Here’s Jalen Hurts running a glance RPO (different run concept, but same principle) back in his Alabama days.

If there’s a college team in the country that doesn’t have the glance RPO somewhere on their play sheet, then they have the slant/flat RPO—one the Eagles run even more frequently than glance. Again, this play asks Hurts to read playside defenders. Here, the unblocked edge chases Sanders, so Hurts pulls the ball, and throws to Goedert in the flat with leverage. The slant/flat combination creates a natural pick, which opens Goedert up consistently.

Teams can dress this concept up with different formations and motions, just to create confusion—but it’ll always be the same process for Hurts: reading the unblocked end to determine whether to throw the ball, and, if he is going to throw, reading the secondary to determine whether to throw to the slant or the flat.

Because this play is so simple, it naturally invites anticipation from the defense and changeups from the offense. That’s the chess match of scheme across the course of a season—predicting defensive adjustments and staying a step ahead of them. Here, Smith bluffs at creating the friction for the slant/flat RPO before turning upfield and breaking into open space—Hurts doesn’t throw with anticipation and has to check down against pressure.

If this all feels painfully simple … well, it is. There’s a reason that college offenses love RPOs. They’re easy to install, they get the ball to athletes quickly, and don’t require five-star quarterbacks to execute. There are also reasons that NFL offenses don’t rely on RPOs nearly as much. As PFF’s Seth Galina wrote last offseason, the league-wide NFL RPO rate hangs at about 8.6 percent, while the RPO rate of Power Five conferences at the college level sits at 21.3 percent.

RPOs appear harder to achieve at the NFL level because of illegal-man-downfield penalties—flags thrown when ineligible receivers (almost always offensive linemen) are more than one yard downfield before the ball is thrown. At the college level, offensive linemen get three yards to climb before they are flagged, so longer-developing downfield RPOs are more achievable. The Eagles have grabbed three such flags in four games, which is tied for the league lead.

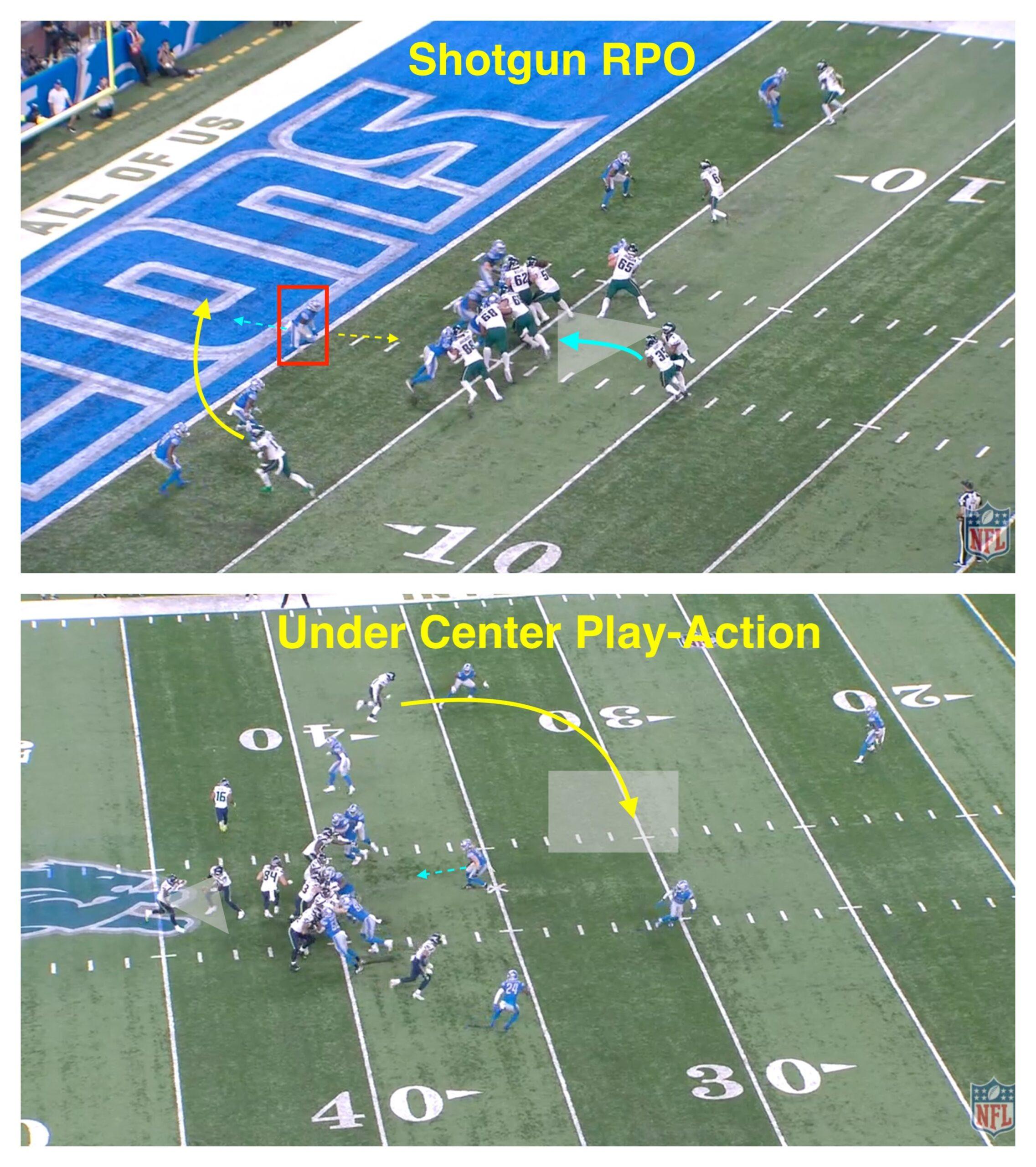

There is another limiting factor on RPOs climbing into NFL normalcy: most post-snap RPOs have to be run from the shotgun. On a shotgun run, the quarterback puts the ball in the belly of the back with his eyes on the defense, while an under-center run forces the quarterback to turn his shoulders and eyes away from the defense as he locates the back and gives him the ball. Unless the quarterback is making a pre-snap decision to throw the ball to a receiver immediately after the snap (like the Packers used to do with Aaron Rodgers and Davante Adams), an RPO almost necessitates a shotgun alignment.

This may seem trite—it isn’t. The majority of runs in the NFL happen from under center; 57.4 percent so far this season, to be exact. And the teams that base their running game out of under-center formations have a more valuable passing option than the RPO: good ol’ fashioned play-action pass. Play-action passes generally perform better from under center than in the gun, because the hard sell of the run fake—the quarterback has his back turned to the defense; the back is coming straight for the linebackers with a head of steam—is more dramatic from an under-center alignment than from a shotgun alignment.

The lines of this dichotomy are blurring (the Falcons play a ton of pistol, for example, to get the best of both worlds), but it remains a generally rigid truth within NFL coaching circles. If you want to run the ball and throw play-action passes, you get under center. If running an RPO requires a shotgun alignment, why bother wasting effort on it? Just get under center, run the football that way, and then hit play-action passes off of your under-center runs.

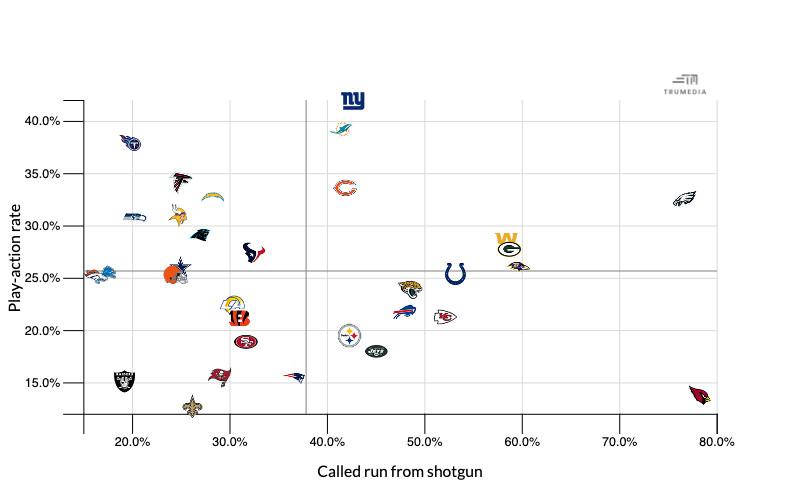

The Eagles offense is flying completely in the face of this guiding principle. The Eagles have had 26 under-center rushes called this year, which is the third-lowest number in the league; they have had two under-center play-action passes called this year, the lowest number in the league. Yet because of their RPO usage, they have one of the league’s highest play-action rates, while also sporting a 76-percent shotgun rate on their called runs. This puts their offense on a total island relative to the rest of the league.

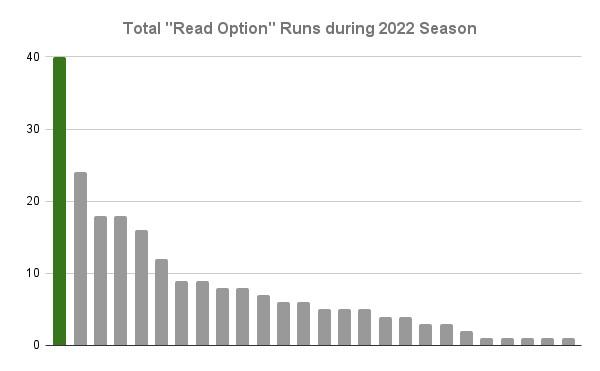

It is not a mistake that two of the most dangerous rushing quarterbacks in the league—Hurts and Arizona’s Kyler Murray—are on the two teams with the highest shotgun run rates. That’s because RPOs aren’t the only play that necessitate a shotgun alignment—so are traditional read-option plays. This is a similar family of plays to RPOs. While RPOs offer the quarterback a run (handoff) and pass (throw) option, read options allow for two separate options to run the football: a give (handoff) or keep (quarterback run). On these plays, Hurts is again reading an unblocked defender post-snap and making him wrong.

Here’s the number of read-option plays called this season by team. Guess which bar represents the Eagles:

The Eagles are a shotgun, RPO-based, read-option-based offense. There are similar offenses in the league—Arizona certainly is one, as are Baltimore and Atlanta when you start folding in pistol stats—but there is no offense exactly like the one that the Eagles are running. And that’s because there is no quarterback exactly like Jalen Hurts.

To run this shotgun, RPO-based, read-option-based offense, you must become comfortable with the idea of your quarterback getting hit. RPOs and read options are going to leave unblocked defenders at the line of scrimmage—and those defenders are going to tee off on your quarterback. On read options, your quarterback might keep the football. When he does, he risks being tackled. Football is a physical game, and any quarterback that crumbles on first contact won’t make it in the NFL. In general, taking a sack from a speeding linebacker while standing still is more dangerous than addressing contact on your own terms as a ballcarrier.

But the rushing quarterbacks who define their offense’s particular approach—think Lamar Jackson and Murray—are often experts at avoiding contact. At 6-foot-2, 230 pounds, Jackson has a wide receiver’s build with impossible shiftiness and acceleration. Murray is 5-10, 207 pounds—that’s the build of a shifty, speedy running back, and Kyler runs like a video game character accordingly.

Hurts is 6-foot-1 and 223 pounds. When Hurts decides to tuck and run, he isn’t looking to avoid contact. He’s looking to initiate and finish. Just ask Devin Lloyd.

Because of the Eagles’ designed running game and Hurts’s scrambling tendency alike, no quarterback has come close to sniffing Hurts’s volume in the running game. Through four weeks, Hurts has 53 carries—the next closest is Jackson at 37. That puts Hurts on pace for 225 carries, which would beat out Jackson’s 2019 record of 176 by a substantial margin—Hurts is averaging over 13 carries per game, while Jackson’s MVP season topped out at 11.7 per game. But remember: Lamar’s magic is his ability to take on glancing contact, to minimize the brunt of the hits he inevitably endures with his running. The same is true for Kyler. It is not true for Hurts, especially with the way the Eagles use him in the red zone.

Perhaps more than anything else—more than ineligible-man-downfield penalties and under-center run/play-action splits—this is what turns the NFL off from this style of play. While the belief that mobile quarterbacks get injured more often is clearly not supported by data, it is a scary thing to pay a quarterback $40-plus million dollars a year and then ask him to regularly tuck and run with the football.

But the Eagles aren’t paying Jalen Hurts $40-plus million dollars. They’re paying him $1.6 million in the third year of a four-year rookie contract as they enjoy the greatest competitive advantage offered to modern NFL teams: the rookie quarterback contract. A.J. Brown, James Bradberry, Kyzir White, Haason Reddick, C.J. Gardner-Johnson—all of these offseason additions are made possible by the unused cap space left over from Hurts’s incredibly cheap deal.

While Hurts is young, cheap, and fresh, this offensive approach doesn’t just work—it dominates. The Eagles offense has more layups—easy completions, free yards—than any other offense in the league. It feels effortless and multifarious. They figure out the one thing their opponent can’t stop in their menu of optionality—quick passes against the Vikings, deep shots against the Commanders, zone read against the Jaguars—and hammer it until the bell tolls.

But the offenses that have dipped their toes into this water tend to add no additional appendages. The Ravens were one of the highest shotgun run teams in the league over the last few seasons—now, they’re under center and in the pistol more, and run more traditional play-action. The Cardinals offense peters out every year even as the running game excels in the gun, as both their play caller’s and quarterback’s limitations prevent them from being much of anything besides a heave-it-to-DeAndre-and-pray passing game. The Chiefs run a ton of RPOs, but without the threat of a legit quarterback run—something they’re not going to risk with Patrick Mahomes—their shotgun running game sputters and their offense rests on the shoulders of the league’s most dangerous thrower. Baltimore, Arizona, Kansas City: they all have better true passers than Philadelphia does.

That’s why the Eagles are in for not just a penny, but a pound. Entering the season, a Hurts-led offense was still not a sure thing—yeah, it looked great to end the 2021 season, but who knew if it’d work long term? Before Hurts’s rookie contract expires, the Eagles’ offensive staff must prove that this is a sustainable model: both in terms of offensive ingenuity, as defenses key in on their simple passing attack and force development from the coaching staff; and in terms of Hurts’s durability and health. As Hurts accumulates tons of rushes and takes tons of hits, the fuse shortens on a powder keg of an offense that relies more heavily on its quarterback’s athletic ability than perhaps any other in the league. And all of those critical supporting pieces? Brown, Johnson, Mailata, Kelce, Goedert? It becomes impossible to pay all of them once the Eagles hand Hurts a second contract.

The Eagles offense rocks. It’s proving to the NFL at large that the inrush of college inspiration is far from over; that quarterback mobility remains an underappreciated and underutilized trait. In four short weeks, it has shown not just that it can win, but also that it can win in different ways on different Sundays—that, eventually, it will find an answer and start pouring points on the board. There perhaps isn’t a more trustworthy offense in the league.

One of two things happens next. It’s possible that defenses catch up, key in on the Eagles’ tendencies, and force them to evolve. The limits on the offense are exposed, and Hurts is stressed to become a winner from the pocket as a traditional dropback passer. Maybe he has enough—he’s gotten better throwing from the pocket every year he’s been a pro—and maybe he doesn’t.

It’s also possible that Hurts ascends into the transcendent plane—into the category of players that aren’t just so good at the one thing they do well, but are so good at the one thing they do well that the rest of it all just doesn’t matter. The category of players that make all of these typing and graphs and charts totally pointless because the rules don’t apply to them. The world-benders, math-changers. The greats.

In the current world of running quarterbacks, that moniker belongs to Jackson and Jackson alone. It is hard to think that a second player will join him. That’s the thing about transcendent players—they’re rather rare. But the Eagles offense is going to try. They’re going to line up every week, point to their quarterback and say, “We can do whatever we want, and because you can’t stop this guy, you can’t really stop us.” And we’ll soon find out if they’re right.