Through four games this NFL season, the Detroit Lions are the league’s highest-scoring team. Now, I could point out that they’re 1-3 after a 48-45 home loss to the Seahawks and have surrendered more points than all but 16 teams in league history through the first month of the season, but Dan Campbell wouldn’t want us to dwell on the negatives. The Lions are the NFL’s most consistent scoring machine at the moment, putting up at least 24 points in each of their games, and they haven’t done it by landing a franchise quarterback, or loading up with talented pass catchers, or finding the next play-calling genius. They did it by building the NFL’s most complex run game.

That hasn’t been a successful blueprint for teams in this era of the sport, as a rule book favoring the offense has made passing easier than ever. But so far this season, star quarterbacks have largely failed to live up to their billing. Look at the teams leading the NFL in offensive EPA through four weeks:

Patrick Mahomes’s Chiefs are at the top, which isn’t much of a surprise, but they’re followed by Jared Goff’s Lions, Jacoby Brissett’s Browns, Tua Tagovailoa’s Dolphins, and Geno Smith’s Seahawks. If you were to extend that list to the top 10, Marcus Mariota’s Falcons would also make an appearance. That Mahomes guy is pretty good, and Tagovailoa has a chance to start for a long time once he returns from a scary concussion suffered in Thursday night’s loss to Cincinnati, but none of the other quarterbacks are viewed as viable long-term answers for their respective squads. They’re role players in offenses designed to make their jobs as easy as possible, whether it’s with a strong running game, a QB-friendly passing game, good play-calling, or all of the above.

With a handful of lower-tier quarterbacks putting up top-10 numbers and leading efficient offenses, one would think that scoring would be up across the league, but the opposite is true. Scoring is down by about one point per game from last year and nearly three points compared to 2020. Michael Lopez of Next Gen Stats wrote about the falling scoring average after last week’s games and found that a decline in passing efficiency was the main culprit.

Quarterbacks were better in Week 4, but passing numbers are still down across the board. The league-average EPA per dropback is 0.02, the lowest it’s been since 2017—which was a strange year for quarterback play due to injuries. Not counting that season, you’d have to go back to 2005 to find a lower EPA average. That was around the time the NFL adjusted its illegal contact rules, which eventually sparked the league’s passing revolution.

In 2017, we could chalk up the declining numbers to bad quarterbacks playing a lot of snaps. In 2022, it’s the established stars at the position who aren’t pulling their weight. Joe Burrow’s Bengals rank 18th in EPA. Matthew Stafford’s Rams are 21st, Russell Wilson’s Broncos are 22nd, and Tom Brady’s Buccaneers are 24th, according to RBSDM.com.

Given the offensive success of run-focused teams like Philadelphia, Miami, Cleveland, Detroit, and Atlanta, and the struggles of the league’s traditional offensive powers and their expensive quarterbacks, it might be time to ask: Why are some of the most prolific passers in the league struggling while their less-heralded peers are thriving?

If you’ve been following the football analytics discourse over the past decade-plus, you know that passing is the most efficient method to move the ball, and that the idea of “establishing the run” is mostly bullshit. Multiple analysts have set out to find a link between rushing volume/success and play-action passes—which remains the NFL’s own version of the NBA’s corner 3—and haven’t had any luck.

So why, then, are offenses built with a run-first mentality doing so well to start the season? Well, the threat of the run may not boost a team’s play-action game—which is how almost every team generates explosive plays now—but it can draw the coverages and fronts the offense wants to see when dialing up those deep shots. As Lopez notes, two-high safety coverages are on the rise:

Rates of Cover-1 man have dropped to 19.8% [in 2022] from a four-year average of 26.5%. Schemes with multiple deep safeties have jumped, including Cover-2 zone (up to 13.8% usage in 2022 from a four-year average of 11.2%) and Quarters (up to 14.7% usage in 2022 from a four-year average of 11.4%).

Historically, two-high safety coverages are typically reserved for obvious passing situations, but now we’re starting to see them more often on early downs. Since 2019, usage rates for Cover 2, Cover 4, and Cover 6, which all fall under the “two-high” umbrella, have jumped while the use of Cover 1 has dropped by nearly 10 percentage points. That’s largely due to the Andy Reids, Sean McVays, and Kyle Shanahans of the world who, by the time Mahomes and the Chiefs hit their stride back in 2018, realized they could exploit single-high coverages for explosive pass plays and avoid long, painstaking drives. As that philosophy swept across the league, defensive strategic shifts became inevitable, and the counterpunch was keeping two safeties back to prevent deep passes and figuring out how to stop the run with fewer numbers.

In general, defenses are now playing more zone coverage, which is designed to give up the short areas of the field in favor of stopping those big plays. So while completion rates are holding steady, the value of those completions has fallen. This season, the success rate for the average completion is the lowest it’s been since 2000, as far back as TruMedia’s data goes.

Two-high looks are particularly effective at forcing short, inefficient throws, and teams like the Bengals, Bucs, and Broncos are seeing them most often. Whether running the ball better would actually get defenses out of those looks is up for debate, but this isn’t: These are the NFL’s three worst running units, and they’re giving defenses no reason to even consider dropping a safety into the box.

Denver, Cincinnati, and Tampa Bay Can’t Run the Ball

The Bengals seem to have figured things out over the past two weeks after struggling to start the season: Cincinnati has scored 27 in each of its past two games; it failed to score more than 20 in its first two. But while the Steelers and Cowboys showed them a healthy dosage of Cover 2 in the first two weeks, the Jets didn’t follow suit in Week 3, and in Week 4, the Dolphins went with their typical aggressive defensive approach, so it’s hard to say whether the improvement will stick. Burrow and coach Zac Taylor are still trying to figure out how to mesh their shotgun-based passing attack and Taylor’s under-center running game—even in the win over Miami, the running game produced just 67 yards on 30 carries.

During Cincinnati’s breakout 2021 campaign, Burrow feasted on single-high safety looks while the league’s defenses were still trying to figure out this young Bengals offense—which led the NFL in yards per attempt and and was tied for the lead in touchdown passes when facing Cover 1 and Cover 3, according to TruMedia. This season, with opponents more focused on stopping Ja’Marr Chase and Tee Higgins from catching deep passes on the perimeter, Burrow has had to adjust his game. His average time to throw and average depth of target are both down, and so is his overall efficiency.

The Bucs have a similar problem. Their offense is obviously built around Brady and a deep receiving corps, but under Bruce Arians, a lot of their explosive plays came on under-center dropbacks after a play-action fake. As Arians explained before Tampa Bay’s win over Kansas City in Super Bowl LV, the most important call in their playbook is a run play nicknamed “22 Double”—a downhill run up the middle with the offensive line working double-team blocks against the defensive front. The downhill nature of the play makes it ideal for running play-action fakes off it.

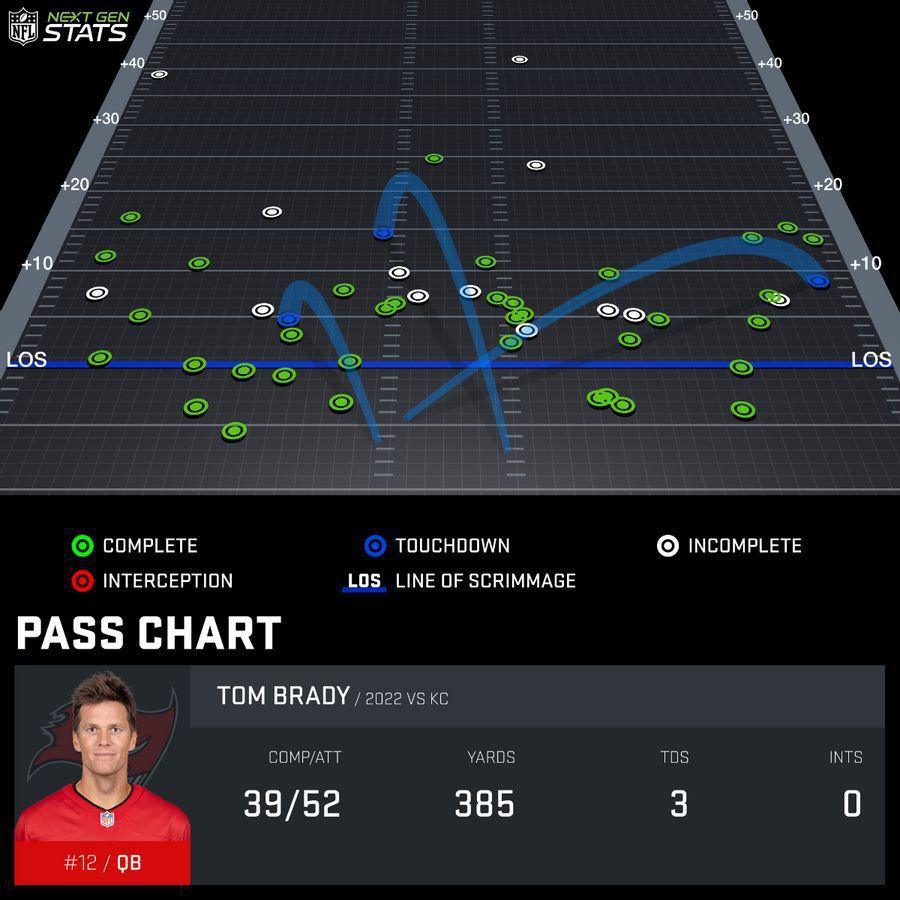

The Bucs haven’t been very good when running “22 Double” this season, for a variety of reasons. They lost their three starting interior offensive linemen in the offseason. Rob Gronkowski, one of the league’s best blocking tight ends, retired. And Chris Godwin, who will motion into the box and block on that play, has been in and out of the lineup due to injury. Not wanting to abandon one of their staple calls, the Bucs spent the first few weeks running into loaded boxes with little success. And instead of trying to find new strategies to open up the run game on Sunday against the Chiefs, they just abandoned it altogether. On 51 early-down plays, Brady dropped back 46 times. He handed the ball off just five times.

Tampa Bay did put up a season-high 31 points in a 10-point loss in the Super Bowl rematch, but it required a heroic effort from Brady to get there. And at 45 years old and playing behind a suspect offensive line, Brady may not last too long if he’s asked to do this on a weekly basis:

The Bucs need to create explosive plays, and until they find a way to get their foundational run call going, it’ll be difficult for the aging quarterback.

Wilson and the Broncos, meanwhile, skipped right past all the success the Bucs and Brady enjoyed early on in their partnership and headed straight for dysfunction. Wilson has had issues that were to be expected—he’s still not targeting the middle of the field nearly enough, and his waning mobility has limited his play-making. But Denver’s run game is at the rotten core of this offense, which produced one scoring drive in the second half of its 32-23 loss to the previously winless Raiders. After that game, in which Melvin Gordon and Javonte Williams combined for 36 yards on 13 carries before losing snaps to two-time starter Mike Boone, the Broncos now rank 30th in EPA per run (ahead of only the Bengals and Bucs) and 25th in rushing success rate, per RBSDM.com.

Wilson has also struggled with consistency. The explosive plays are still coming in the passing game—Wilson connected on two beautiful deep balls against the Raiders to spark a touchdown drive in the second half—but he’s finding little success on the plays between. The 33-year-old’s dropback success rate (the percentage of his pass plays that produce a positive EPA) of 38.1 percent ranks behind Mitchell Trubisky, Carson Wentz, and Joe Flacco. This is a boom-or-bust attack that’s going bust an overwhelming majority of the time. And without a reliable run game to keep Denver ahead of the chains and Wilson out of obvious passing situations—when defenses play the two-high coverages that give him so much trouble—I’m not sure how this offense is supposed to function. This situation is starting to look a whole lot like what we saw in Seattle before Wilson’s ugly departure.

Meanwhile, Pete Carroll’s Seahawks rank fourth in rushing EPA, and Smith just so happens to be leading the NFL in several major passing categories, including completion percentage and completion percentage over expectation, while helming the under-center, play-action-heavy running game offensive coordinator Shane Waldron couldn’t get going with Wilson.

Now, the Bengals, Bucs, and Broncos don’t have to transform into the 2019 Ravens, or even Campbell’s Lions, to get their offenses rolling. But they do have to figure out how to run the ball in a way that commands the defense’s respect. That’s necessary for two reasons: First, defenses tend to play more single-high safety coverage when an offense isn’t in the shotgun—and that holds true even when you eliminate obvious passing situations. Second, it helps to slow down the pass rush, and all three of these teams have had issues in pass protection—whether it’s an offensive line issue or a quarterback issue. Per Next Gen Stats, the average “get off” time for pass rushers drops when the offense is under center:

Average “Get Off” Time for Pass Rushers, Since 2018

Once again, that holds true even if you just look at first-down snaps, when the threat of the run is at its highest.

Average “Get Off” Time Since 2018, First Down Only

As things currently stand, Cincinnati, Tampa Bay, and Denver are making their quarterbacks play on hard mode. They’re constantly asking them to make difficult throws to tight windows while dealing with pressure. And without even a mediocre run game to help relieve some of that pressure, things will only get tougher as defenses realize there isn’t a need to save their best coverage and blitz calls for third down.

I’m not here to suggest that Campbell and the other coaches leading these surprisingly effective offenses have stumbled onto a new way to build a championship team. This league will always be dominated by superstar quarterbacks. But now that defenses are finding new ways to cope with spread passing games, teams need to have at least a respectable run threat before those superstar quarterbacks will be able to live up to their lofty standards.

The run game may never be truly back, but the first month of the NFL season has shown us that it at least can’t be forgotten.