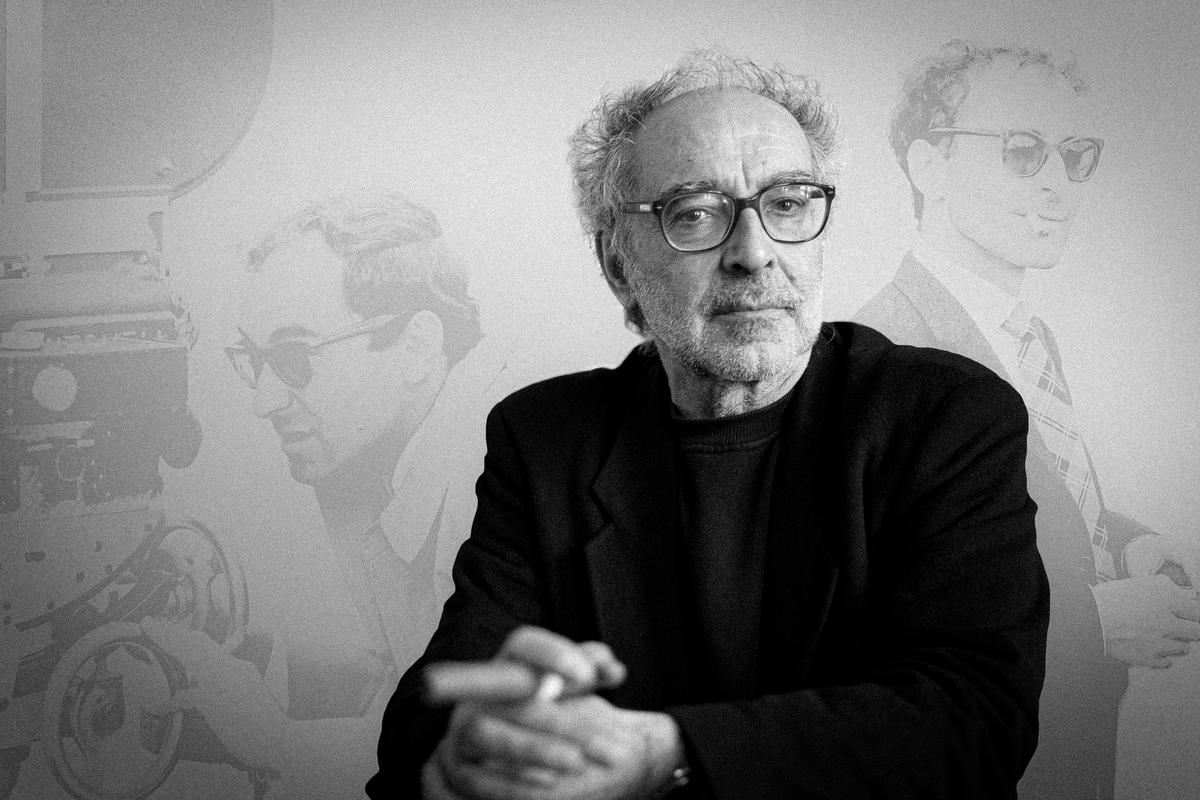

In a career that spanned nearly 60 years and includes more than 40 feature films—a career that helped codify one of the most important formal movements in the history of a medium and exploded its potential for political comment—Jean-Luc Godard did virtually everything except make a movie that is two hours long. That habitual brevity could cast the French Swiss filmmaker, who died Tuesday at the age of 91, as a shrewdly economical master of story (he was) or as a mischievous little boy, running around until he tires himself out (that, too). But his audacious blend of exuberance and poise ensured that Godard’s films, copied and copied and copied though they were, could never be replicated in a way that would fool a viewer more than a few frames.

Godard was born in Paris in 1930 to a physician and the heiress to an investment banking fortune. His childhood was interrupted by World War II and the rise of fascism in Europe; he and his family spent most of the war in Switzerland, making only brief returns to France. As a teen Godard was not a film obsessive, rather the kind of charismatic quasi layabout who dots the upper crust. He thought he might paint, or write novels, or become an anthropologist, but was a disinterested student. By about 1950, however—when he had more or less written off his classes at the Sorbonne—Godard had fallen in with a group of young enthusiasts who would soon become France’s critical vanguard, including those who founded the totemic Cahiers du Cinéma.

This cadre of critics turned filmmakers, which also included Francois Truffaut, Éric Rohmer, and Jacques Rivette, came to be known as the French New Wave. The directors rejected what Truffaut called, in a bit of damning faint praise, French cinema’s “tradition of quality”: films that were stiff and literal, too desperate for validation as literature or the visual art of the past. They argued instead for a new approach that leveraged the medium’s unique capacities and made room for the intertextual allusion, existential riffs, and political charge that marked their conversations with one another. Truffaut’s 1959 debut, The 400 Blows, was in many ways the movement’s big bang, a movie that makes youth feel both alienating and endless and ends with the lead character staring directly at the audience.

Godard’s own debut from the following year, Breathless, follows a young man who kills a police officer before holing up with an unwitting lover—an American transplant. The man is obsessed with Humphrey Bogart, and though he lives through the basest, most harrowing situations a young French person could at that moment, all of them are filtered through a pop-cultural affect, where every movement is self-conscious, every tic learned. (Breathless seems to argue: Isn’t this true for all of us anyway?) The viewer does not need to strain to find the neurotic self-probing in a movie whose first line translates to, “After all, I’m an asshole.”

Aside from the postmodern bleed of imagism into instinct, Breathless became renowned for its great technical innovation, the use of jump cuts. Beyond its obvious practical benefits (saving time, moving plot), the technique has the effect of making a character’s movement between moments of moral conundrum both urgent and arbitrary. It also makes obvious the director’s presence over what is happening on screen. The tension between this nagging reminder and the documentary style of photography and lighting make Breathless one of the most singular films of the 20th century, hyperreal and fantastical at once.

Several of Godard’s early masterpieces, including 1961’s A Woman Is a Woman—where a character played by Jean-Paul Belmondo, who had played the lead in Breathless, says he wants to watch a TV broadcast of Breathless—star his first wife, the actress Anna Karina. It was through Karina that Godard learned the power that movie star charisma has over an audience, and the power that a filmmaker can gain by withholding it. In 1962’s Vivre sa vie, where Karina’s Nana resorts to sex work after leaving her husband and young child to pursue a career in movies, she and her ex-husband speak for more than eight and a half minutes before either one’s face is seen in anything but a cloudy café mirror.

The acuity with which Godard understood the din in young people’s heads was not limited to his tracing their cinematic interests. Toward the end of the ’60s, he began making expressly political films, though these, too, existed in a world choked by commercial entertainment. An intertitle in 1966’s Masculin Féminin refers to characters as “The children of Marx and Coca-Cola.” In 1968 he and Truffaut protested the Cannes Film Festival on the basis that the films it was showing were not in solidarity with workers. A decade later, after being commissioned by the government of Mozambique to make a short film, he excoriated Kodak for its film stock’s inability to capture the nuance in dark skin.

In a catalog that includes musical comedies and askance, not-really adaptations of Shakespeare—3-D larks about dogs who translate couples’ arguments and experiments in handheld digital photography—Godard’s personal restlessness is never far out of the frame.

Godard is one of the most widely quoted figures in film. You likely know many of his maxims even without their being attributed to him: “A film consists of a beginning, a middle and an end, though not necessarily in that order”; “Every edit is a lie”; “Photography is truth—the cinema is truth 24 times per second”; “Art is not a reflection of reality, it is the reality of a reflection”; “All you need for a movie is a girl and a gun.” The final one is undoubtedly his most repeated, and seems to have been absorbed by studio executives the world over as inviolable marketing wisdom. But Godard attributed it to the American director D.W. Griffith; he was simply borrowing it. For an artist whose work was so gleefully intertextual, it’s fitting that Godard’s most famous advice was swiped from someone whose techniques he warped and politics he surely despised.

Tuesday, after word of his death spilled out in the press, another quote of Godard’s began circulating online, one that was notable not for its tidiness, but for its deference. In a 1983 interview with Film Quarterly, he said:

I find it useless to keep offering the public the “auteur.” In Venice, when I got the prize of the Golden Lion I said that I probably deserve only the mane of this lion, and maybe the tail. Everything in the middle should go to all the others who work on a picture: the paws to the director of photography, the face to the editor, the body to the actors. I don’t believe in the solitude of an artist and the auteur with a capital “A.” … In general, there is a tendency today to consider the problems of the director without thinking that behind him there are many other figures equally important in the making of the film.

He was right about the labor that actors and crew members put into film productions, and about the creative consequences their work can have. But few filmmakers did more to advance the idea of the auteur, or to argue for its value. In Godard’s work authorship is both inescapable—in the way he fractured the old cinema’s rote reality to approach an emotional one—and philosophically fraught, as a thousand worries and references hedge against even the simplest of stories.

Godard died at his home in Rolle, Switzerland, on the northern shore of Lake Geneva, where he had reportedly undergone an assisted suicide procedure that is allowed under Swiss law. His lawyer told The New York Times that Godard had suffered from “multiple disabling pathologies,” while a family member told several newspapers that he “was not sick—he was simply exhausted.” (In what is perhaps the more telling, though equally cryptic, quote, the lawyer said to the Times that his client “could not live like you and me.”) Whatever weariness had set in by his 10th decade of life had been assiduously kept from his work. His final release, 2018’s The Image Book, is a prismatic essay film that, from at least a few angles, argues that the West’s cinema has calcified reductive narratives about the rest of the world, particularly the Middle East, while eliding much of its own history.

Largely an act of collage, The Image Book mutates bits of other films—some famous, some Godard’s own—to the degree that many are barely recognizable, and most come to feel wholly new. Without the benefit of actors or a script, the auteur’s hand reaches through history to tap the familiar in a new rhythm, to new ends.

Paul Thompson is a writer based in Los Angeles. His work has appeared in Rolling Stone, New York magazine, and GQ.