Logan Paul might be WWE Champion someday. His WrestleMania match with the Miz—and against the Mysterios—made it clear that he had talent. But it was his SummerSlam match against the Miz which established (at least in the Palace of Wisdom) that Paul feels like a star that could sell out a stadium for a marquee match. Some of this is Paul’s doing, as he does appear to have pushed himself to get in the kind of ring shape—both aesthetically and functionally—that would prevent him from blowing up in the third-longest match of the night (and the second-longest match not involving a tractor that evening) while looking good doing it.

He’s also, for whatever his faults, a brilliant self-promoter who knows what attracts—positively and negatively—people to him, which might be the single hardest bit of the sports entertainment business to wrap your head around as someone in the business, but is SOP for influencers/social media superstars such as himself. Whatever “it” is, Paul has that; and what happened on July 30 in Nissan Stadium was a testament to that.

Ultimately, though, almost none of it would have been possible without the Miz, which just makes me feel old. Not quite as old as the Miz, especially not with the kind of accelerated aging two kids can have on you, but old enough to feel twinges of pain whenever someone mentions Sidney Crosby’s twilight years or I see Tim Tebow working the desk on SEC Nation.

There, of course, are any number of reasons to feel our age, but watching the Miz work the crowd into frenzied support of someone that nearly every single prominent wrestling expert saw as a natural heel (and essentially irredeemable as a babyface) hit me right in my heart. And that’s because, however old I am—the technical term is, I believe, “elder millennial”—it’s “old enough to remember when Mike Mizanin was the guy on The Real World and not the guy from The Real World.”

That I also distinctly remember the first time “Mike” became “the Miz”—though less in an “origin story” than a “reference made in a Marvel movie to another part of the MCU” kind of way—doesn’t help me feel any younger, either. Fourteen-year-old me (with his giant-ass head) didn’t necessarily make the connection that Mizanin wanted to be a professional wrestler and he definitely didn’t think Mizanin would become a professional wrestler. Back then, Big Head (my honest-to-God family nickname at the time) just thought it was peculiar that someone who wasn’t a wrestler, working for a wrestling company, or being paid to talk about it, cared about wrestling.

Mostly, though, that version of me was convinced that the version of “Mike” I had seen to that point was a bit of a dipshit. Mizanin had already spent the first few episodes of the show getting rightfully skewered by his New York housemates for the aggressively stupid things that came out of his mouth. At best, I thought Mike would end up being a dumbass who became slightly less of a dumbass when he was pretending to be “the Miz.”

Which basically remains true to this day—at least on TV—but this version of me (in addition to a head finally in proportion with the rest of his body) has a lot more respect for Mike and the Miz. With Mike, it’s mostly the recognition that people on TV are still people; but with the Miz, it’s a little more complicated. Mostly because it’s difficult to wrap one’s head around just how great the Miz has become.

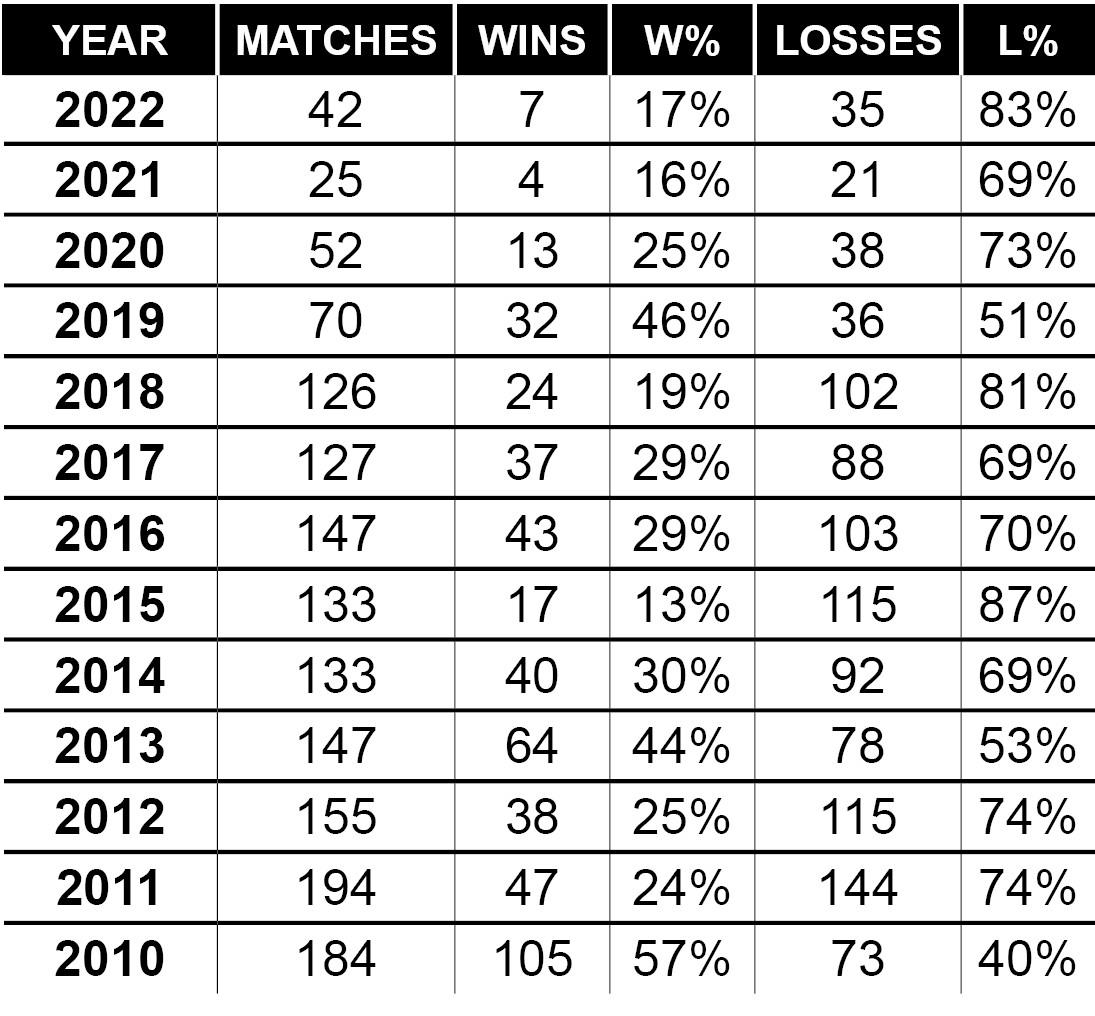

He is a two-time Grand Slam champion, one of the WWE’s most important mainstream ambassadors, and definitely the company’s go-to hand holder for almost every single person who comes into the WWE Universe from the broader world of pop culture; but the idea that he is also, for instance, an unequivocal first-ballot Hall of Famer still feels strange to say. This might be because he’s done so while putting up (at least for the last 10 years or so) what are, for all intents and purposes, “best of the Brooklyn Brawler” numbers.

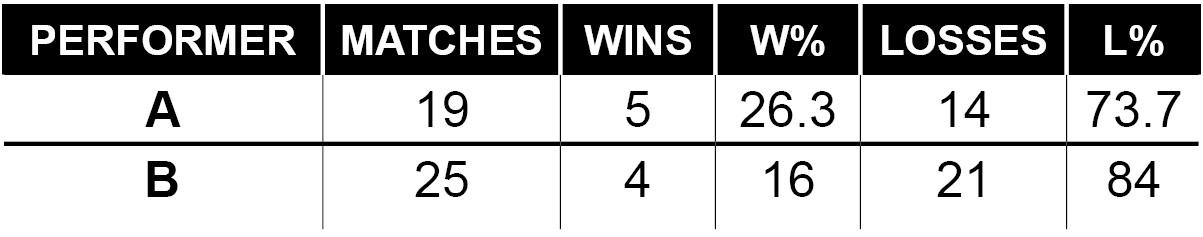

And if you think I’m just mouthing at you, you should ask around about me. I have absolutely no conscience about these things:

If you guessed which numbers belonged to whom, a can of Coke to you: Steve Lombardi—the man underneath the Brawler’s tattered Yankees shirt—is “A,” in 2000. Picked, essentially, at random, this was a year in which Brawler happened to have his most significant televised performance in a 3:21 handicap tag match victory against Triple H (or maybe it was the 1:44 victory over Just Joe on an episode of Jakked later that year—it’s a real toss-up). While B is obviously then the Miz, the year being 2021 is at least a little surprising when you consider it’s also the year he won the WWE Championship from Drew McIntyre.

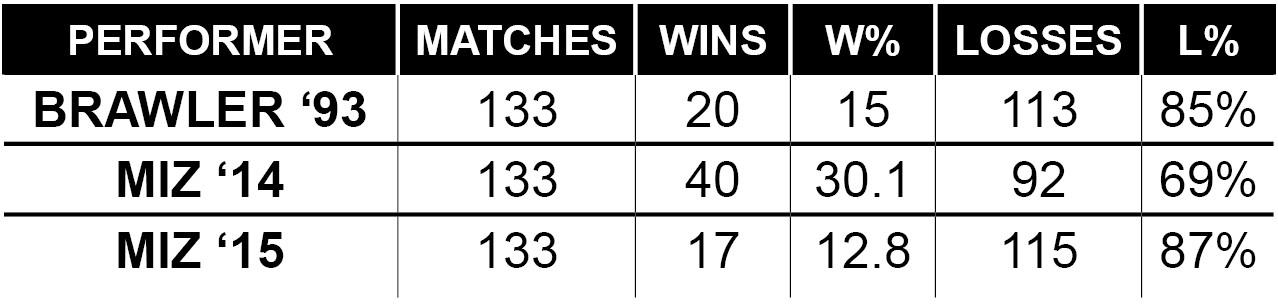

The years aren’t cherry-picked, beyond looking for years with a comparable number of matches. Nor are these just small-sample-size chunks of Miz’s otherwise illustrious 2010s.

And, to be sure, these represent some of the worst years, stats-wise, of Miz’s career, but there are a lot of bad years from which to choose since he won his first WWE title:

The Miz has, to be as clear as possible, won significantly more matches than Lombardi, and has a winning percentage nearly triple that of the Brawler/Abe “Knuckleball” Schwartz/Third Doink (which, to be honest, isn’t saying much). But The Most Must-See Superstar in WWE History hasn’t won more than half of his matches in a single year since doing so in 2010.

Most importantly, he’s completely off the Big Board, ranking 29th out of the 32 competitors we currently track.

And, yet, there he was, with Logan Paul working the second-biggest match of the night at the second-biggest show of the year. Then, just the next week, guiding yet another gifted performer to a midcard title match and brighter future so that Mizanin can eventually turn on them once his (character’s) need for their spotlight (and, usually by extension, their title) overtakes him. He is, essentially, the Crying Jesse Pinkman GIF in human form.

That’s because the matches Parma, Ohio’s favorite son has managed to win in that time have led to fairly impressive results: four (of his six total) Tag Team, eight Intercontinental, and two WWE championships. Both world championship reigns were won by cashing in Money in the Bank contracts (one earned mostly by hook, the other mostly by crook).

He also successfully defended his first WWE Championship in the main event of WrestleMania XXVII (in 2011, an otherwise disastrous year for him record-wise), has worked 50 other singles matches on WWE pay-per-views, and over 100 PPV matches total so far. It’s an extensive list that includes Miz partnering with the Brawler for Lombardi’s only PPV win (and not coincidentally, Lombardi’s only non-battle royal PPV appearance) in a trios match alongside Alberto Del Rio against 3MB at 2012’s TLC PPV.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that wins and losses don’t matter—it’s not a coincidence that the Miz’s two world title reigns started with a Money in the Bank cash-in, as his character would have had a hard time getting an opportunity otherwise—but what wins and losses mean has changed for performers like the Miz. And by “performers like the Miz” I am, of course, talking about the Shayna Baszlers, Natalya Neidharts, and Happy Corbins of the WWE Universe.

They are representatives of a very specific kind of archetype that does not require a regular diet of wins in order to have a seat at the table. Which is the nicest way I can think to put to you all the fact that this bunch has lost (and continues to lose) a lot—as of 8/8/22, 286 times in 383 matches since 2021 started—but do so with the kind of soaring aplomb that you almost have to admire.

Now, you might be saying, “That’s not flying, that’s falling with style.” And fundamentally, you’d be right. But, and here’s the thing: It’s always been falling with style. From “Iron” Mike Sharpe (the patron saint of ham-n-eggers at the Institute of Kayfabemetrics) on through, no one whose job it was to make other people look better has ever spent all that much time actually looking great themselves.

But what has changed is that, in transitioning from a fake sport they were trying to make look real into a show about a fake fighting league—I’ve described it as “Sports Night as written and performed by the cast of American Gladiators” in the past—WWE (and wrestling promotions in general) lost the credibility they once had to have the audience inherently trust them regarding someone’s legitimacy. Did anyone watching World Championship Wrestling on Saturday nights in the ’80s genuinely think the Mulkey Brothers or George South were a legitimate threat to the established stars they were about to be fed to?

For the love of God, no!

But the presupposition was that they were legitimate participants in the sport of professional wrestling (which was then subject to outside validators like athletic commissions). Now, in order to have someone you are essentially paying to lose feel like a legitimate competitor (and not just as glorified “extras”) to fans, you occasionally have to let them win, and sometimes big.

The Miz is perhaps the most prominent example, but Happy Corbin ran Raw, retired Kurt Angle at WrestleMania, and has procured a number of WWE’s minor milestones like winning the ’Dre, King of the Ring, and that old midcard classic, a failed run with the Money in the Bank briefcase. Corbin also has legitimate athletic credentials as a former NFL practice-squad player for the Cardinals and the Colts, as well as a (regional) Golden Gloves boxer.

And for folks like Natalya, their legacy (and considerable in-ring acumen) can insulate them from too much reputational damage. Natalya—as she may have mentioned at some point—is a member of the Hart family, the first female graduate of the Hart Dungeon, and the owner of two (short) world title reigns, once as SmackDown Women’s champion and another as WWE Divas champion.

As it is with the Miz, she is almost certainly a Hall of Famer. But unlike Mike, she has had at least a few years of serious contention over the past decade—she won a shocking (at least to us) 82 percent and 76 percent of her matches in 2015 and 2013, respectively. She has also had the bottom fall out over the last three years after a resurgent period between 2018 and 2019, winning less than 25 percent of her matches since then (and in spite of a surprise Women’s Tag Team title reign with Tamina in 2021 that was nearly as long as her other two title reigns combined).

Natalya has settled into this role almost perfectly—her character work, especially on Twitter, has been some of the best of her career—and at least this year she has performed much of her duties alongside perhaps the most interesting member of this crew, Shayna Baszler. Once one of the most dominant performers in the history of NXT—she held the women’s title on two separate occasions for more than 500 days combined—Baszler’s career since then has gone ... differently.

The Queen of Spades has won only 55 of her 151 matches since joining the main roster at the 2020 Royal Rumble, and has won just six of her 50 matches this year. Despite her truly abysmal record, like the Miz, Corbin, and Natalya, it doesn’t seem to stop Baszler from being booked into prominent matches, which in her case is an upcoming SmackDown Women’s Championship match against Liv Morgan at Clash at the Castle.

That she earned the title shot essentially clean—your mileage may vary on how “legit” her taking down an exhausted Raquel Rodriguez at the end of a gauntlet match is, but she didn’t cheat—is something that could only be done by someone with her background. As a legit shooter who could presumably beat most of the roster inside an octagon, all WWE usually needs to do to “justify” her getting a title shot is give her the most slight advantage possible in a chaotic environment and let her work her considerable in-ring magic.

Such booking is not uncommon amongst these folks, as unlike their predecessors (who existed almost entirely as cannon fodder), this group of gatekeepers usually confer legitimacy on their opponents, not simply the significance of arrival. Everyone regularly on the show has now been established as “mattering” in the modern WWE, and as such, these aren’t just players at the bottom of an unknowably long depth chart. They have evolved into characters on the TV show that WWE has created, and needed to be treated in the way we’ve been trained to expect on other TV shows.

Which meant a transition from regarding everyone in this role as Red Shirts to treating them the way Parks and Recreation handled Jerry/Terry/Garry Gergich: someone against whom the universe conspires, often terribly, but who’s rewarded with enough nice and profound moments—and a beautiful family—to balance finding out they were adopted as part of an office “game” or almost dying during a “fart attack.”

There hasn’t been the wrestling equivalent of a “fart attack” since Rikishi’s last Stinkface, but if there was, it would likely be working with what could best be described as “celebrity guest wrestler,” as that can so often be the drizzling shits (an industry term for a, well, crappy match). Because WWE has been able to raise its profile in such a way that it has begun attracting legitimate stars like Bad Bunny, Logan Paul, and (in her own way) Ronda Rousey; the holding of their hand has become the most important way in which this role has changed, both in how WWE books the bottom of the card and structures a considerable chunk of their promotional focus.

Although Vince McMahon and WWE have commodified it in the wrestling industry, celebrity has always played a role in promoting nearly every kind of spectacle since the dawn of commerce. But wrestling is unlike, say, having someone cut a ribbon at the opening of a ... mall? (Is that still a thing that happens? Do malls open?) Or pop their head in for an appearance on a radio/television show/Twitch stream.

Wrestling is something that requires training and has legitimate stakes beyond (but also including) “No one cared who I was until I put on the mask (to sing).” The closest equivalent would be debuting your stand-up comedy routine while starring in a theme park stunt show that the rest of the crew is going to improv through most of, more often than not in front of tens of thousands of paying customers. Which is something that, at the WWE level, really only happens with celebrities.

Almost every single full-time performer on the roster is well-trained enough to not hurt anyone through negligence and inexperience or completely fall flat on their own face. In order to sustain the product at the scale to which WWE has grown accustomed, celebrities must be included in its presentation, but given their lack of training (and sometimes, lack of understanding of the product itself, though that has largely shifted in the last 10 years or so) they present both metaphorical and literal liabilities. Of course, because of the promotional stakes (and the injury risks) it would make the most sense to pair them with the performers whose clout would allow them the largest benefit of the doubt in terms of getting their match “over.”

However, given that those kinds of performers are (in modern wrestling), almost always at the top of your card, this is where “someone like the Miz,” or in the case of Logan Paul, the actual Miz comes in. Because, despite Lesnar’s “Brock Glass in Case of Emergency” status, it’s performers like the Miz—who made it clear in his now legendary promo on Daniel Bryan Danielson—that make these shows work as well as they do.

This is also what ultimately makes these performers “enhancement talent” in the best way possible: They make both the company and their opponents look better than they probably deserve, often at the expense of their personal success without asking for nearly anything in return.

Just the occasional obscure trophy or title match at a second-tier PPV, the respect of their peers, and if it’s not too much, well-paying jobs for as long as they are willing to do them.

Nick Bond (@TheN1ckster) is the cofounder of the Institute of Kayfabermetrics and provides weekly updates to The Ringer’s WWE Power Board.