Gene LeBell, who died on August 9 at age 89, led a life so expansive that any mere retelling of it would come across like a tall tale, the stuff of Pecos Bill and Paul Bunyan—if all of it weren’t true.

LeBell lived long enough to learn submission wrestling from the likes of Ed “Strangler” Lewis, study judo in postwar Japan, win the first notable mixed martial arts match in 1963 and then referee the much-hyped but disappointing 1976 proto-MMA showdown between boxer Muhammad Ali and wrestler Antonio Inoki, trade fighting tips and blows with a young Bruce Lee on the set of The Green Hornet, allegedly choke out martial-arts action star Steven Seagal on the set of Out for Justice in 1991, and even decline an invitation to the early Ultimate Fighting Championship events when he and 82-year-old jujitsu pioneer Hélio Gracie couldn’t settle on a fighting weight. Along the way, he trained scores of future greats in a variety of disciplines, from “Rowdy” Roddy Piper in wrestling to “Rowdy” Ronda Rousey in judo (she, too, eventually wound up in the wrestling business), and even managed to extricate himself from being convicted in the 1976 murder of a private detective who had been digging up dirt on a host of California notables.

LeBell’s roots in combat sports ran deep. His mother, Aileen Eaton, was a promoter at the Olympic Auditorium in Los Angeles, where she promoted boxing and wrestling events and raised Gene and his brother Mike all by her lonesome. For most of Eaton’s time in the business, she was the only major female fight promoter in the United States, possibly even the world. It was in her promotion that a Texas-born grappler named George Wagner first donned an elaborate robe, dyed his hair blond, walked to the ring with a valet, and became the 1950s television sensation “Gorgeous George,” the “toast of the coast.”

While men like Wagner and later Freddie Blassie and Dick “the Destroyer” Beyer would headline Eaton’s wrestling cards, the young LeBell—bereft of a father figure—started at the very bottom, learning the ropes in the hardest away imaginable, twisted into pretzels by grapplers like the aging Evan “Strangler” Lewis, from whom LeBell asked to learn the Strangler’s signature headlock when LeBell was the tender age of 7.

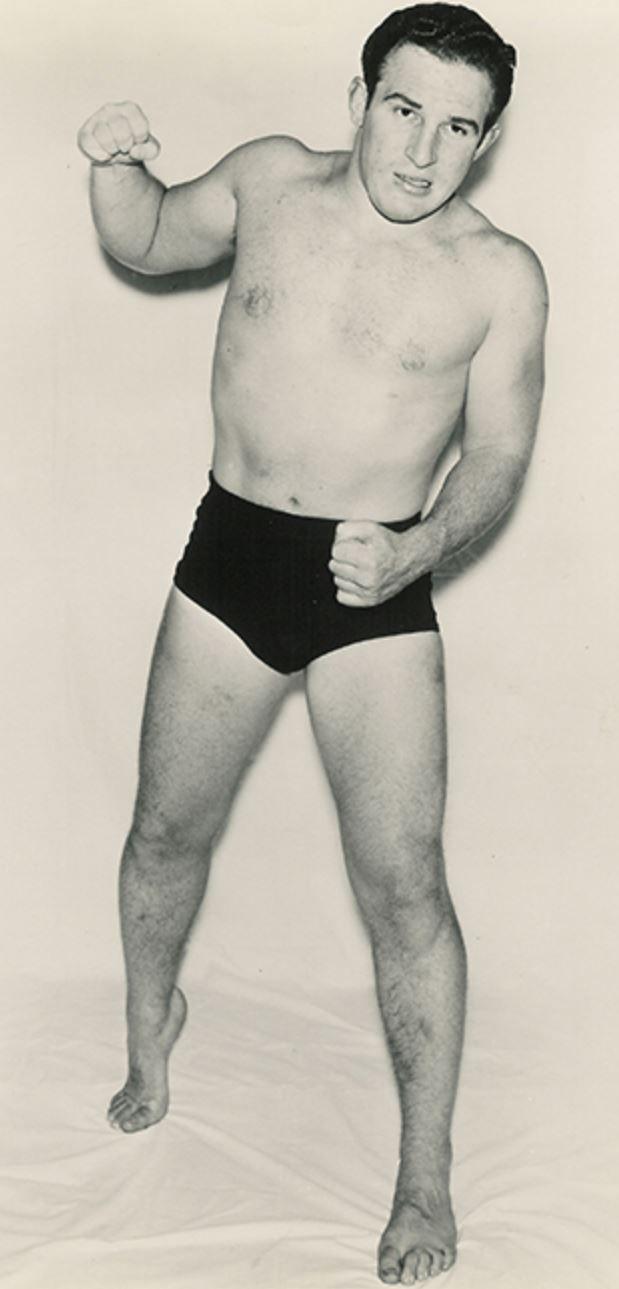

By the time he transitioned to judo in the early 1950s, LeBell had already spent untold hours in submission holds and on the receiving end of punches from boxers like the great Sugar Ray Robinson at L.A.’s famous Main Street Gym. When he entered the 1954 AAU National Judo championship as a lightly regarded 160-pound heavyweight, he pinned 1952 Pan American Games gold medalist Johnny Osako in his first match, then went on to win both his weight class as well as the overall tournament. He repeated this dominant performance in 1955, winning all but one of his 18 matches solely with standing throws.

Although LeBell would remain undefeated in the sport for eight years, even traveling to Japan in 1955 to further his judo skills—and, following a laundry mishap, adopt the pink gi that became a signature piece of his in-ring look—his interests were too varied to allow him to focus exclusively on one sport. For LeBell, one martial art naturally flowed into another; they were already mixing together in his curious mind. “Judo is wrestling with handles,” he told Black Belt magazine in 1994. “If you want to do a ‘whizzer’ throw in wrestling, it’s the same as an uchimata [inner thigh throw] in judo. The only thing that is different is that judo has strangleholds, which aren’t done in pro wrestling.”

Although LeBell considered full-time careers as a boxer and a judoka, the lure of better money in pro wrestling and Hollywood stunt productions—as well as connections to both industries—led him into those fields. “I was told that all the judo and karate people were not making any money at that time; they were starving,” LeBell recalled in that interview. “So they said I could make good money in professional wrestling, which I did. I made very good money, and it led me into a career in stunt work.”

LeBell was never a main-event star in wrestling and by even the most generous assessment wasn’t exactly a crowd-pleaser in the ring. In his book Shooters: The Toughest Men in Professional Wrestling, long-time MMA journalist Jonathan Snowden described LeBell as “a horrible professional wrestler from a technical perspective,” a tough guy who “looked soft in the ring” and remained stuck on the undercard of his brother Mike LeBell’s wrestling events, wrestling under his own name or beneath a mask as “the Hangman.” He did claim to have won the NWA World Heavyweight Championship in 1960 from Pat O’Connor in a match in Dory Funk’s Amarillo, Texas, territory, repeating this assertion to both Black Belt and Sports Illustrated, but the victory was almost certainly part of a wrestling story line, with LeBell accidentally striking the Texas wrestling commissioner with the belt and forcing its immediate return to O’Connor.

Freddie Blassie, who starred for Aileen Eaton and Mike LeBell for decades, wrote in his autobiography Legends of Wrestling: Listen, You Pencil Neck Geeks that LeBell’s believability in the ring wasn’t what mattered to Mike and Aileen—it was his credibility: “When the family needed an enforcer to step into the ring with a wrestler who didn’t want to go along with the program, all they had to do was open Gene’s bedroom door and tell him to get into his wrestling gear.”

LeBell’s wrestling fortunes varied—his brother Mike told Sports Illustrated in 1995 that he had fired Gene on several occasions, noting that “sometimes even I thought he was crazy”—but his career continued its upward trajectory as he moved into the Hollywood stunt work that would see him participating in thousands of projects over the years. However, he had one last sports achievement on the horizon: an actual mixed martial arts bout—said by some to be the first of its kind, though there were boxer-versus-wrestler antecedents in prior decades—in 1963 against middleweight boxing gatekeeper Milo Savage, whose lengthy career was winding down.

According to a 2014 interview in Black Belt, LeBell had no idea the fight would be as significant as later developments in the sport of MMA have made it. The promoters were looking for “karate and judo bums”—very distinct striking and grappling specialties, though LeBell knew the basics of karate—to fight a boxer, whom LeBell assumed would be Jim Beck, a highly regarded amateur who had called out the practitioners of those sports. Eager to claim the $1,000 purse—“I’d fight my grandmother for $1,000, but she’d have beaten me,” LeBell said—the judoka found himself facing not Beck but Savage, who not only was an accomplished professional boxer but a man with a solid knowledge of wrestling fundamentals.

As described in Jonathan Snowden’s Shooters, the match was a gripping affair, with the gripping part complicated by the fact that instead of wearing a loose judo gi, as he had promised, Savage instead showed up in a tighter-fitting karate gi intended to make it difficult for LeBell to grab and hold him (below-the-waist takedowns of the sort that LeBell believed to be most effective against boxers were barred). Extant fight footage shows a stocky LeBell, probably 60 to 70 pounds heavier than he was when he debuted in judo, cautiously circling and then struggling to throw the much smaller man, who exhibited sound wrestling defense. However, the writing was on the wall for Savage: LeBell threw and then mounted the boxer in the second round, although he couldn’t secure a finish, then hip-tossed him in the fourth round before using a gi choke to render his foe unconscious—much to the displeasure of the crowd, which was unused to seeing people choked in this way.

It wasn’t exactly an elite-level boxer facing down a grappler, but it did offer a variation on the Ultimate Fighting Championship model that LeBell’s long-time acquaintances, the Gracie family, would partner with Bob Meyrowitz to launch in 1993—right down to the initial audience confusion and cautious feeling-out process between the athletes. Seventeen years before the UFC debuted, though, LeBell refereed arguably the most notable mixed martial arts clash of the era, serving as the third man in the ring for the Muhammad Ali–Antonio Inoki superfight in Tokyo. Hamstrung by rules barring takedowns, strikes on the ground, and submission holds, the fight devolved into a tedious 15-round affair in which Ali taunted and showboated while Inoki crab-walked along the mat, kicking Ali’s legs. The damage inflicted definitely favored Inoki, who battered Ali’s legs sufficiently that “the Greatest” struggled with his mobility in a fight against Ken Norton later that year, but LeBell—who had Inoki slightly ahead on his own scorecard, per the account in journalist Josh Gross’s book Ali vs. Inoki: The Forgotten Fight That Inspired Mixed Martial Arts and Launched Sports Entertainment—chose to deduct points for an illegal groin strike, thus affording Ali a split-decision draw that showcased how dull MMA could get without the appropriate rules in place.

LeBell’s years of stunt work and fight choreography also introduced grappling to the world of action movies, where it is now commonplace to see fighters turned actors such as Randy Couture and Gina Carano using submission holds in their action sequences. While working with rising martial arts star Bruce Lee on the set of The Green Hornet, LeBell was instructed by the stunt coordinator to subdue the actor—who was said to be terrorizing the stuntman for a particular scene—and did so by quickly grabbing Lee in a fireman’s carry and running around the set with him.

In a recent conversation with Bob Calhoun, the coauthor of LeBell’s autobiography The Godfather of Grappling, the judoka, then 87 years old, said he was surprised that Lee “didn’t try to counter me, so I think he was more surprised than anything else.” In the years that followed, Lee worked with LeBell to incorporate grappling into his films, defeating Sammo Hung with an arm bar in Enter the Dragon and Chuck Norris—who would become another long-time collaborator of LeBell’s—via chokehold in Way of the Dragon. Some have pointed out that LeBell making easy work of Lee on set may have inspired the scene in Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood in which Brad Pitt, playing veteran stuntman Cliff Booth, has his way with Bruce Lee (played by actor and martial artist Mike Moh) in an on-set sparring match. However, no context is provided for the encounter—up until the fight, Booth’s martial arts credentials, unlike LeBell’s, are completely unknown, and he defeats Lee on the feet rather than with wrestling techniques.

LeBell also gained notoriety for the way he dealt with the notoriously eccentric and aggressive Steven Seagal on the set of the 1991 film Out for Justice. Seagal, a towering man who had a background in the Japanese martial art of aikido, has long battled with stunt choreographers and fight trainers on set—in Shooters, Jonathan Snowden quotes Pride announcer Stephen Quadros’s story of engaging in an uncomfortable series of wristlock exchanges with Seagal on the set of the 2001 film Exit Wounds—but by most accounts (and there are many), his encounter with LeBell went poorly.

The simplest version of the tale has Seagal boasting that he couldn’t be choked out, and LeBell, then in his 50s and significantly smaller than the 6-foot-4 actor, going behind the star, then taking him to the ground and choking him out. More embellished versions include details about Seagal defecating himself. Seagal himself denies the entire situation, calling LeBell a “sick, pathological scumbag liar,” though even Seagal’s former bodyguard Steven Lambert tells a version of the story that has Seagal attempting to resist LeBell’s application of the hold before winding up on the ground, though remaining conscious throughout. LeBell, preferring to let others do the talking for him, told MMA journalist Ariel Helwani in 2012 that “if thirty people are watching, let them talk about it.”

LeBell’s career wasn’t without controversy of its own, though—not long after refereeing the Ali-Inoki fight in 1976, he was arrested for his role in the murder of private investigator Robert Duke Hall, whose residence contained hours of phone recordings connected to powerful local figures and even the 1972 presidential campaign of Richard Nixon. In a story worthy of the detective novels of Raymond Chandler, LeBell, who drove California pornography magnate Jack Ginsburgs to the murder scene, was acquitted on a murder charge but convicted and sentenced to probation as an accessory for his role in transporting Ginsburgs to the murder—a conviction later overturned by the California Court of Appeals in a heavily fact-dependent decision based on careful interpretation of state rules of evidence rather than any new proof of LeBell’s innocence. In any case, LeBell was back to work in the movies almost immediately, adding to the movie residuals and Screen Actors Guild–backed retirement that sustained him in his later years.

Over the course of this six-decade career, LeBell had a hand in training many prominent players in the entertainment, wrestling, and MMA worlds. In addition to Bruce Lee and Chuck Norris, LeBell also tutored the likes of Roddy Piper (who claimed in his autobiography to have received a black belt in judo from LeBell, though this is likely as spurious as the impossible-to-verify Golden Gloves championship he was sometimes reported as having won), Olympic bronze medalist judoka and future UFC and WWE star Ronda Rousey (who always cited him as an important mentor), American judo champion and instructor Gokor Chivichyan, and Chivichyan’s Armenian American judo student Karo Parisyan, one of the first notable judo practitioners in the UFC.

Despite this long legacy in the worlds of pro wrestling and MMA, LeBell, always chasing the smart money, never hung around too long on the mat in either sport: “There’s only 1 in 1,000 MMA fighters who make money,” he told Black Belt magazine in 2014. “A lot of fighters are broke. The only thing I have against MMA is they don’t have a retirement plan. In the stunt world, I get a pretty doggone good retirement from SAG and AFTRA—and I can still work.”

For 89 years, few did that work better than “Judo” Gene LeBell.

Oliver Lee Bateman is a journalist and sports historian who lives in Pittsburgh. You can follow him on Twitter (@MoustacheClubUS) and read more of his work at www.oliverbateman.com.