Sports announcers have a lot of money and a bit of fame. What they seek is universal love. At the moment of their greatest success, they wonder why they haven’t managed to convince every last Twitter account they are talented and worthy. None of them will ever make the sale, except for maybe Vin Scully.

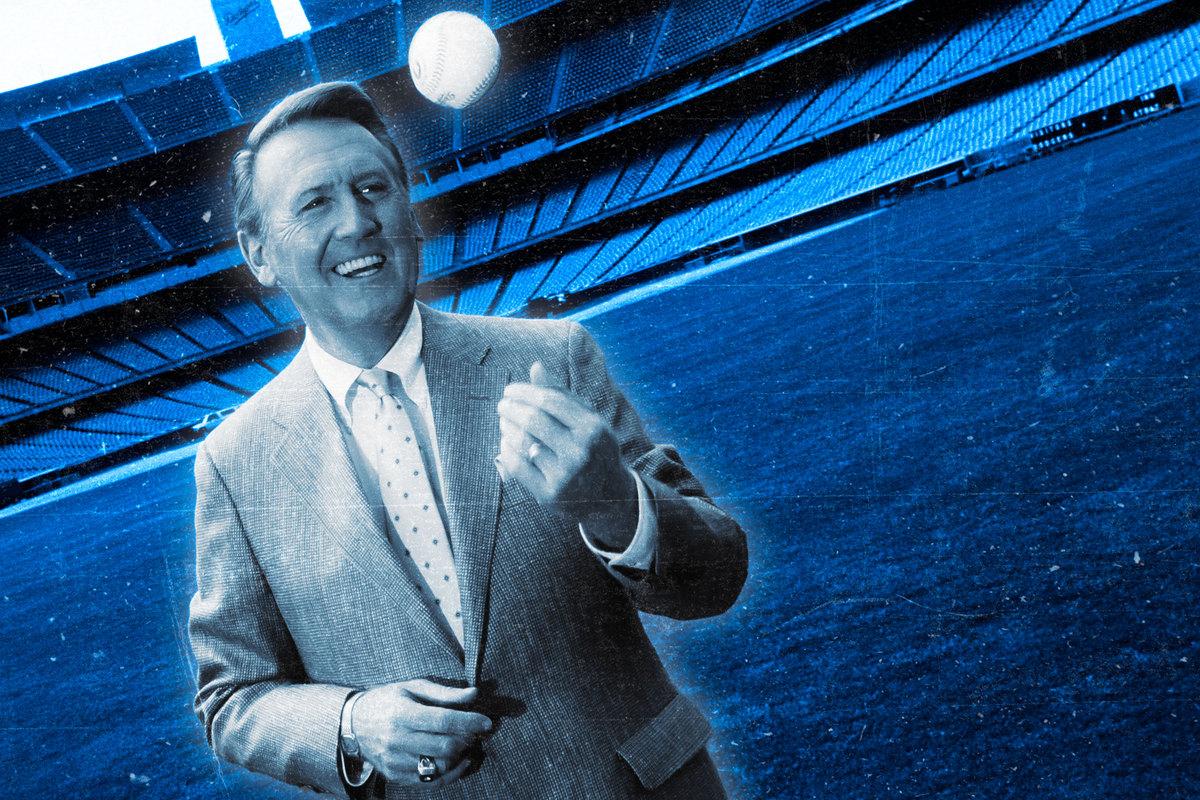

Long before his death Tuesday at age 94, Scully was the rare announcer who had something close to a 100 percent approval rating. Scully was loved by the graying keepers of baseball’s flame. By Angelenos and non-Angelenos. By media writers, who beckoned him to come out of the bullpen and call an inning of the World Series before he retired. Even the proprietors of Old Deadspin collected his musings on socialism and drug paraphernalia. I believe there are announcers who can call a baseball game with a semblance of Scully’s skill. Few will make viewers want to give them a hug.

What was lovable about Scully, first and foremost, was his manner, which was avuncular until it was grandfatherly. Listen to Scully call Kirk Gibson’s hop-along homer in the 1988 World Series. “High fly ball into right field,” he said, the electricity creeping through his voice, “she is … gone!” That “she” is something else, a pronoun Scully managed to smuggle into the ’80s.

Scully always offered a portal to baseball’s past. He was like a Joe Posnanski column in a powder-blue sports coat. Curt Smith’s biography notes that, as a kid, Scully liked to slide underneath the family’s radio, so that he could be surrounded by the sound of distant games. Scully went to college at Fordham (later the way station for Mike Breen and Michael Kay). In 1950, the Brooklyn Dodgers gave him a spot on the broadcast team. Five years later, at age 27, Scully got to say, “Ladies and gentlemen, the Brooklyn Dodgers are the champions of the world.”

Viewers may love announcers for their wiseassery (Al Michaels) or bracing, full-on confessional (Joe Buck). On the air, Scully offered nothing but smiles. “I’m the great cover-up,” he told Rick Reilly in 1985. “I don’t talk about my sadness. … [Tommy] Lasorda always says to me: ‘You’re always happy.’ Well, I’m not always happy, but I try to act like I am.”

Scully’s career fell in such a way that allowed his fixed smile to stay in place. In 1975, when he went national with CBS, the Dodgers allowed him to remain on their broadcasts. Most announcers are known for their team logo or the emblem on their network blazer. Scully wore both and was bigger for it.

On the night Scully called Gibson’s home run, he was 60 years old—only seven years older than Buck is today. But NBC lost the rights to baseball the next year. It was the last time Scully ever called a World Series on TV.

After that, Scully mostly retreated to Dodgers broadcasts, where he spent the next 28 years aging gracefully in front of people who loved him unconditionally. There were few critics wondering whether Scully had lost his fastball, no Funhouse Twitter account, no demand for a succession plan. It always amused me to see people who had never lived in Los Angeles talk about driving around and listening to Scully on a summer night. Tucked away on the West Coast, Scully became something bigger than an announcer. He became a collective memory.

Study Scully’s career and you’ll see the TV industry showed him no more reverence than it did any other broadcaster. Scully called Dwight Clark’s catch in the 1982 NFC Championship Game. “I got on the airplane, flying back home, and I thought, ‘You know what? It can’t get much better than that,’” Scully said later. “That would be a great game to walk off on. And so by the time that plane landed, I had quit football.”

In fact, that season, CBS had pitted Scully against Pat Summerall in a public bake-off to see who would make a better partner for John Madden. The network decided that Scully and Madden were volume shooters who wouldn’t work well together. So Summerall got the midcareer turbo boost and the ’82 Super Bowl; Scully got the NFC Championship Game as what turned out to be a parting gift. He left CBS for NBC.

In a new book, longtime Los Angeles Times sports TV columnist Larry Stewart writes of one knotty encounter with Scully. A headline that ran over a 1983 Stewart column noted that Scully liked calling baseball games solo—which was true when he worked with the Dodgers. But the headline appeared just as Scully was starting a new NBC partnership with Joe Garagiola, one that was cast as a delicate merger of egos. Scully got angry and said he wouldn’t talk to Stewart again.

“For me, this was like a break-up call from a girlfriend,” Stewart writes. Being an L.A. columnist who feuded with Vin Scully was like being an L.A. meteorologist who knocked sunshine. Sure enough, after Stewart praised Scully’s work in subsequent columns, Scully went back to being his benevolent self.

Watching announcers seek love from their audience is almost heartbreaking. It’s such a doomed quest. For one thing, the plastic smoothness we demand from announcers, the quick recognition of that fly ball to deep right field, makes it nearly impossible for them to be lovable.

Another problem is the demands of the job. A football game may offer 10-second longueurs, a baseball game slightly longer ones. Only a few announcers ever figure out how to show something of their personality in those spots. Of those who do, only a tiny number are found to be lovable.

A still smaller number of announcers manage to stifle their self-love long enough to admit the adoration of the crowd. Here, Scully was the absolute master. “It’s only me,” he told Dodgers fans when the team honored him for winning the Ford C. Frick Award in 1982. He said almost the exact same words when the Dodgers celebrated his retirement 34 years later.

In 2016, when media writers asked if Scully would call one last inning of the World Series or All-Star Game, he demurred. He didn’t demand one more ovation. He would be content with the murmur of appreciation he’d been receiving for years. The key to finding something like universal love, Scully discovered, is to venture an opinion few announcers ever have. It’s to say that everybody’s making too much of you.