Asked in November which team he might model the Mets on, new owner Steve Cohen said, “I like what the Dodgers are doing.” In January, his team traded for a franchise player who was one year away from free agency and disinclined to sign a sweetheart, hometown deal, 11 months after the Dodgers had done the same with Mookie Betts. And less than three months after that, the Mets cribbed from the Dodgers’ Betts playbook again by signing that superstar to a lengthy extension on the eve of Opening Day. Late on Wednesday night, the Mets and shortstop Francisco Lindor agreed on a 10-year, $341 million extension that will take effect in 2022 and keep the 27-year-old Lindor off the free-agent market through 2031, his age-37 season. In unadjusted dollars, it’s the third-largest contract in MLB history (after the 12-year extensions for Mike Trout and Betts), and about 2.5 times larger than the most prodigious deals of the Wilpon ownership era. Trout and Betts, appropriately enough, are also the only position players to out-WAR Lindor since his debut in 2015.

We’re not far removed from the flurry of coverage that followed the Mets’ trade for Lindor and Carlos Carrasco, and what we wrote and said then still applies. By FanGraphs WAR, Lindor has been the best shortstop in baseball over the past six seasons. During the same span, Mets shortstops ranked 21st, and they’d be even lower than that if the defensive component of FanGraphs WAR were based on defensive runs saved rather than ultimate zone rating. (Mets shortstops ranked 29th in DRS from 2015 to 2020.) The durable, lovable Lindor has paired an elite glove with an above-average bat in every season, garnering Rookie of the Year or MVP votes in each campaign and picking up two Silver Sluggers and Gold Gloves. Though he’s not a lock to repeat his 38-homer barrage from 2018 (his best offensive season to date), his .258/.335/.415 line in 60 games last season reflects neither how well he hit the ball then nor how well he’s expected to hit now. Even after that down year, Lindor has a five-win baseline and a seven-plus-win upside, which makes him one of the dozen best-projected position players, and he gave Mets fans an early look at his skills by slashing .370/.433/.630 in spring training.

Extending the superstar, a move that seemed almost inevitable right up until a temporary impasse in the hours before Lindor’s Opening Day deadline, doesn’t change the Mets’ outlook for 2021. What it does do is cement the Mets’ renewed commitment to spending like the big-market titans they are. Cohen’s comment in his introductory press conference seemed to signal a new direction for the franchise, but until it was backed up with action, his words wouldn’t mean much. Twenty-eight other MLB ownership groups undoubtedly like what the Dodgers are doing; who wouldn’t like winning eight straight division titles and three pennants in four years, and then entering the season after winning a World Series with an outside shot at setting the single-season wins record? But liking what the Dodgers are doing is a lot easier than doing what the Dodgers are doing.

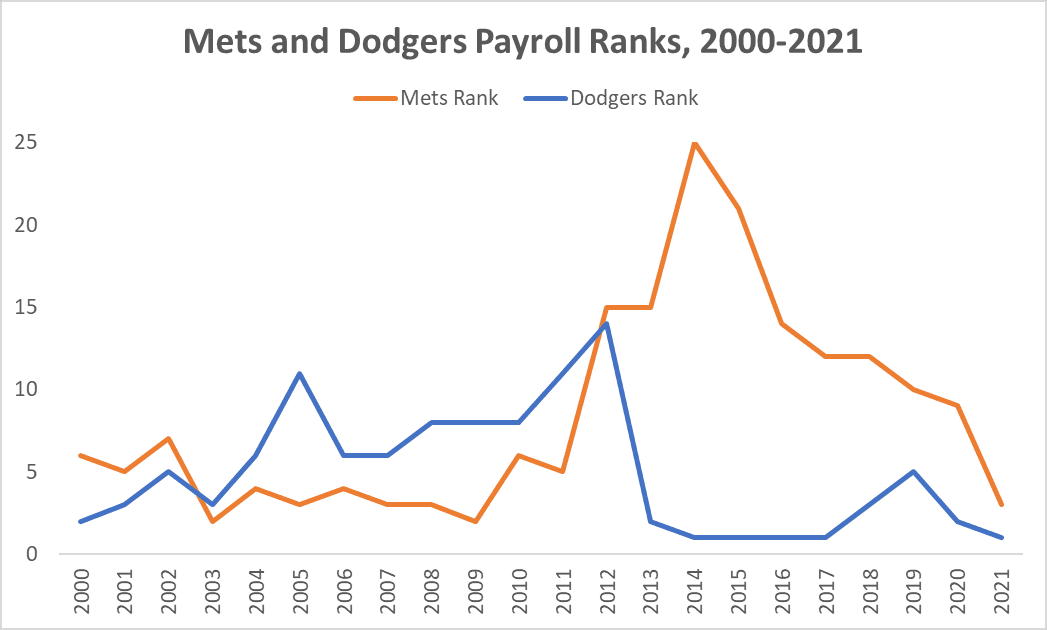

The Mets are far from making good on their goal of fielding a perennial playoff team; this weekend, COVID permitting, they’ll try for their first regular-season win since Cohen bought the club, with Lindor likely batting in the second spot. But in one respect, they already resemble the Dodgers more than they have at any point since L.A.’s division-title streak started. For the first time in almost 10 years, the Mets have come close to spending like Los Angeles again, and the Lindor deal helps ensure that they’ll continue to. The graph below shows the two teams’ annual payroll ranks over the past 20 years, according to Cot’s Contracts, and their projected 2021 payroll ranks courtesy of Roster Resource. Although the Mets haven’t blown by the competitive balance threshold the way the Dodgers did by re-signing Justin Turner and adding Trevor Bauer, their $199 million Opening Day total trails only the Dodgers and Yankees.

From 2000 through 2012, the Mets’ and Dodgers’ payroll ranks tracked each other closely: On average, the Mets ranked fifth in payroll, and the Dodgers ranked seventh. Their win total ranks were within hailing distance, too: ninth for the Dodgers, and 14th for the Mets, which translated to an average difference of five wins per year. The two teams’ payrolls diverged in 2013, when the newly flush Dodgers—who had been purchased by the deep-pocketed Guggenheim group the previous March and had just landed a $7 billion TV deal—became one of baseball’s biggest spenders. Meanwhile, the Madoff-deprived Mets—whose payroll had plummeted in 2012, coinciding with a settlement in the Ponzi scheme suit against the Wilpons—remained in the middle of the pack despite playing in the country’s largest media market. During that just-concluded period, the Dodgers’ average payroll rank was second, compared to the Mets’ 15th. Not coincidentally, the average gap between the two teams in wins expanded also, to almost 16 per season.

A Tale of Two Payrolls: Mets and Dodgers

That the Mets’ leaguewide rank in wins barely budged (from 14th to 16th) in the latter stretch even as their payroll rank sank from fifth to 15th is a testament to their player development. Over the past several seasons, the Mets benefited from having drafted and developed the likes of Jacob deGrom, Matt Harvey, Seth Lugo, Michael Conforto, Pete Alonso, Jeff McNeil, Daniel Murphy, and Dominic Smith, signed Jeurys Familia as an amateur free agent, and traded for Noah Syndergaard and Zack Wheeler prior to their big league debuts. When it came to constructing a championship-caliber core of young, cost-controlled players, the Mets were almost Dodgers-esque: From 2015 to 2020, they ranked fifth in the majors in on-field value produced by homegrown players (defined as players who had only ever appeared in the majors with one team), as measured by Baseball Prospectus’s wins above replacement player (WARP). The Dodgers ranked first.

Most Homegrown Team WARP, 2015-2020

The Mets’ ability to generate wins from within made it all the more frustrating that the latter-day Wilpons were, with rare exceptions (such as Yoenis Céspedes), unwilling or unable to supplement that inexpensive talent with the complementary pieces that could have put them over the top (or at least made it much less likely that they’d miss the playoffs in every season since 2016). In WARP from non-homegrown players, the Dodgers ranked third, but the Mets came in 14th. Thus, they were never bad enough to be hopeless, but never good enough to stop squandering the head start they had from their homegrown talent. The Mets produced essentially the same homegrown WARP total as the Astros in that six-season span, but the Astros identified smart trade targets, improved and spent on those players, and ranked first in non-homegrown WARP. The Mets were, at best, only slightly less dysfunctional than the notorious Rockies, whose homegrown WARP total ranked seventh but who averaged about 2 WARP per season from non-homegrown players because they utterly flopped in free agency, spending more than $300 million for a sub-replacement return.

There’s no WARP for ownership, but the Wilpons were replacement level or below. Not only did they fail to spend on player payroll in a way that was commensurate with the Mets’ market, but they didn’t invest in the front-office talent and technology that enabled small spenders like Tampa Bay or Cleveland to compete, and they also insisted on interfering with on-field affairs. To some extent, ownership is destiny: A team can win by spending a small amount of money efficiently or a large amount of money inefficiently, but it can’t win without an ownership group that empowers the right people to do one or the other—or, in the Dodgers’ case, the best combination of both (a large amount, efficiently).

Cohen seems to understand this. In the same November address in which he invoked the Dodgers, he committed to hiring capable people, deferring to their judgment, and giving them the tools to thrive. He talked up the team’s homegrown talent, pledged to strengthen its farm system, and said, “You build champions. You don’t buy them.” Crucially, though, he also said, “When we need to fill a gap, we will fill it.” That’s the part the Wilpons didn’t do.

The Mets filled a gap when they acquired Lindor, an upgrade that more homegrown major league talent (Andrés Giménez and Amed Rosario) made possible. But until they extended him, fans scarred by years of Wilpon penny-pinching braced themselves for more missing out. The Mets signed James McCann instead of splurging on J.T. Realmuto. They lost out on George Springer (to Toronto) and Bauer (to the Dodgers). At times during the last week, as the shortstop reportedly stuck to a 12-year, $385 million demand and the Mets held firm at 10/325, it looked like they might let Lindor leave too.

The shortstop and the Mets made things interesting, not least because Cohen kept up a social-media dialogue about the Lindor deal, jokingly (?) crowdsourcing contract terms and tweeting about the contract taking two to tango. (One thing the Dodgers don’t do is tweet about their stars’ dinner orders during contract talks, though at least we now know that Lindor is partial to chicken parm.) Those updates might have looked reckless, or at least less amusing, if Lindor hadn’t signed, but the two sides came to terms, literally at the 11th hour.

Lindor will receive a $21 million signing bonus, followed by flat $32 million annual salaries for a string of 10 seasons. WAR can’t quantify charisma, but the projected price for the Mets is $10 million per win, roughly in line with what Betts should cost the Dodgers. Presumably for symbolic, ego-saving/dick-measuring reasons, Lindor’s extension tops Fernando Tatis Jr.’s recent pact by $1 million, though none of the money in Tatis’s deal was deferred, whereas $5 million a year of Lindor’s salaries will be paid annually from 2032 through 2041 (which will be several years after the final Bobby Bonilla Day). Tatis was also younger and further from free agency, and he signed for 14 years, so the deals aren’t quite comparable, but technically Lindor and his agent can point to the total and say “Scoreboard.”

The contract contains a 15-team no-trade clause and no opt-outs, which makes it likely that Lindor will call Queens home for the remainder of his career, or at least for the rest of his prime. Aaron Judge may own New York now, but Judge, who’ll turn 29 this month, is signed only through next season. The Yankees showed with Robinson Canó—another homegrown star who hit free agency after his age-30 season—that they’re willing to let homegrown stars walk, and if Judge departs or breaks down, Lindor plays to his potential, and the Mets make good on Cohen’s Dodgers dream, the magnetic shortstop could capture the city the way Derek Jeter did. Lindor’s smile is a signature as scintillating as Jeter’s jump-throws and fist pumps, and no one will make GIFs of grounders going “past a diving Lindor.”

Lindor’s removal from the board reshapes next winter’s free-agent market, though a quartet of star shortstops—Corey Seager, Trevor Story, Carlos Correa, and Javier Báez—remains unsigned past 2021. It also affects the future of the Mets’ internal talent: The team’s top (or, according to some sources, second-ranked) prospect, Ronny Mauricio, who’ll turn 20 on Sunday, hasn’t played above A ball, but he’ll eventually be forced to shift from short to third lest he become trade bait. Unless, like Jeter, he refuses to move, Lindor might not stay at shortstop for even half of the life of this deal: Only one of last year’s 10 most valuable shortstops (Miami’s Miguel Rojas), and only four of the 25 players with the most plate appearances as shortstops, were 30 or older. But Lindor’s defense is so special today that he can surrender a step or two before his next stop on the positional spectrum becomes a topic of conversation.

Both the Betts and Lindor trades were widely condemned because Boston and Cleveland, respectively, didn’t pay market rate for franchise players that they conceivably could have afforded (another example of ownership dictating destiny). It’s bad for competitive balance when teams trade productive fan favorites for financial reasons, and for the faithful in Cleveland who watched him mature, the sight of Lindor in a Mets uniform will sting for some time to come. The silver lining is that the league, like the universe, is bound by the law of conservation of mass: When players like Lindor and Betts are transferred between teams, those superstars are neither created nor lost. They’re merely embraced and beloved by different fan bases.

One trade and subsequent extension doesn’t make the Mets the Dodgers or guarantee that Cohen will be hoisting a trophy within three to five years. It doesn’t address the flawed front-office structures and processes that the Jared Porter and Mickey Callaway harassment scandals revealed, and it doesn’t settle the statuses of the other prominent Mets who aren’t locked up long term. But it does reestablish the Mets as one of the sport’s coastal elites, at least in terms of payroll. Wins and playoff appearances are likely to come next. A little more than two years ago, Cleveland owner Paul Dolan infamously said about Lindor, “We control him for three more years. Enjoy him and then we’ll see what happens.” What happened, predictably, is that Lindor was dealt. Now he’s Mets fans’ to enjoy. And they’ll enjoy him very much, for more than a decade.

Thanks to Lucas Apostoleris of Baseball Prospectus for research assistance.