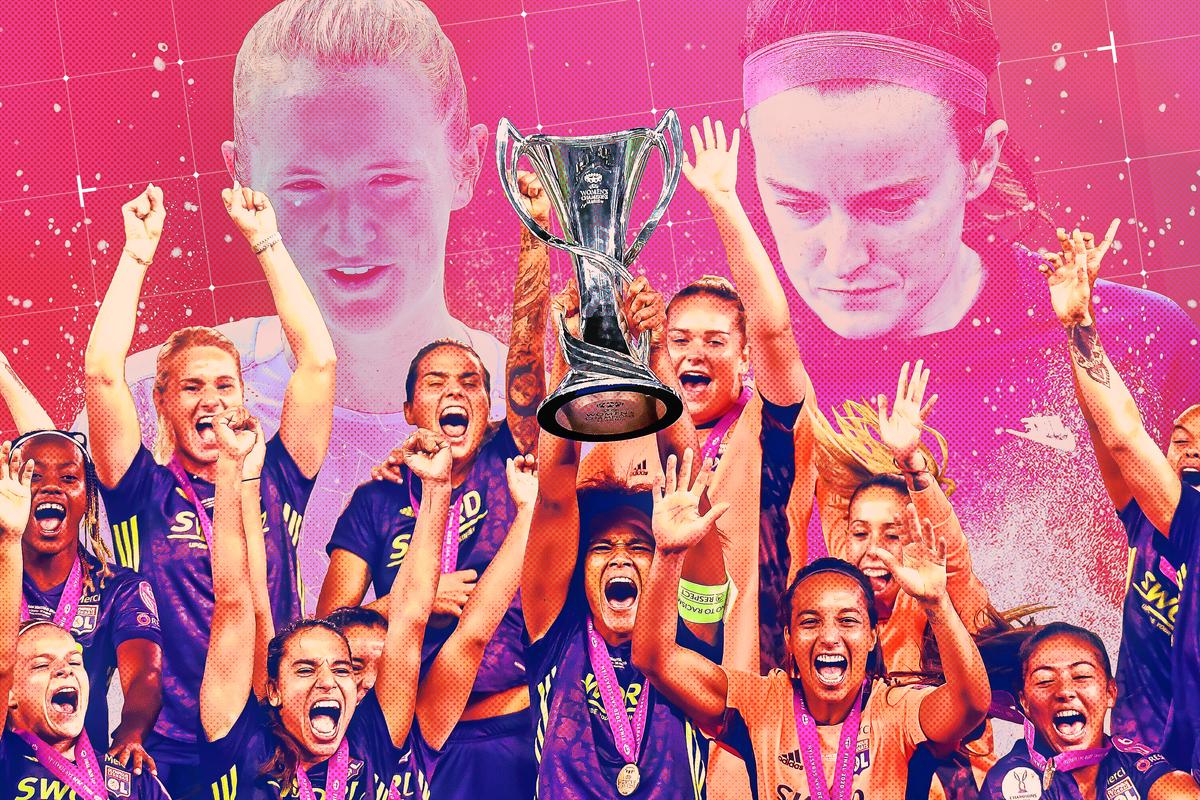

Lyon’s Dynasty Continues, but the Competition Is Catching Up

The French side won a fifth straight Women’s Champions League, but Europe’s competitive balance might be shifting to England. Teams like Manchester City and Chelsea are investing more in their women’s teams, including luring some American stars overseas.

Something had to give: Sunday’s Women’s Champions League final featured a Wolfsburg side that had been undefeated since May 2019 against Lyon, the last team to beat them, whose own unbeaten streak extended even further, to May 2018. Ultimately, Wolfburg’s run came to an end in San Sebastian’s Anoeta Stadium. Lyon, the all-conquering, star-packed, unstoppable force of women’s professional soccer, dismantled the team that many had suggested were best equipped to prevent them from winning their fifth-straight Champions League title and seventh overall, continuing the most dominant era the women’s game has ever, and will most likely ever, see.

Lyon’s 3-1 win showed how far ahead they are of the chasing pack. They were missing two major goal threats: Nikita Parris was suspended after being sent off in the semifinal; Ada Hegerberg, the 2018 Ballon d’Or winner, who’d bagged a hat trick in last year’s final, was still recovering from an ACL injury; and Amandine Henry, captain of the French national team, started the game on the bench due to a minor injury. Lyon still cruised thanks to goals from Eugénie Le Sommer, Saki Kumagai, and Sara Björk Gunnarsdóttir, the latter joining from Wolfsburg in July just before the tournament resumed. Despite a goal from captain Alexandra Popp to make the score 2-1 in the second half, the German league and cup champions never really looked like they’d walk away with their first Champions League since 2014. Wolfsburg—which started as Volkswagen’s club for its factory workers—was up against the soccer equivalent of a finely tuned F1 car that never needed to reach top gear.

The results of the Champions League knockout games, played over one leg instead of two, showed some leveling of the playing field between Lyon and the rest of Europe’s top teams. Lyon may have been surprised that their progress to the final came courtesy of two victories by a single-goal margin. After eliminating Bayern 2-1 in the quarterfinals, Paris Saint-Germain made Lyon grind out a 1-0 win. But in the final, Lyon showed how overwhelming the air of invincibility can be for their opponents. The speed at which they moved the ball and switched the point of attack was dizzying, overloading one flank before seamlessly moving to the other. At times, it just didn’t seem fair, with Lucy Bronze and Delphine Cascarino teaming up on the right and Sakina Karchaoui and Amel Majri on the left. Throw in a midfield three of Kumagai, Gunnarsdóttir, and Dzsenifer Marozsán—operating under the watchful eye of captain and club legend Wendie Renard—and any opposition would be forgiven for not wanting any part of them. Lyon toyed with Wolfsburg like a cat with a mouse, never wanting to kill them, merely pawing at them, as if for their own enjoyment.

Lyon’s success is no fluke, nor is it down to one generational coach or solely having world-class talent—it’s a product of a culture. Club president Jean-Michel Aulas has run the club since 1987 and created the women’s side in 2004. It took the women’s team three years to win their first league title in France; no other side has won it since. Aulas has shown what’s possible when a club—not even one of the richest 15 in the world—invests in their women’s team anywhere near as much as their men’s team. Both share the same training facilities and travel on private charter flights. After both teams reached the Champions League semifinals, Aulas handed out equal bonuses. “It is a pleasure to be the president of this team,” he said. Who wouldn’t be proud of what Lyon have achieved?

While Lyon’s development into a dominant power has been a deliberate process spanning more than 15 years, it highlights what’s possible when financial and institutional support is given to the women’s game. It is entirely at a club’s discretion whether or not to have a women’s team. Just as clubs invest in youth infrastructure, from U-23 teams down to grade-school-age academies, they can support their women’s teams. Lyon are the trailblazers of narrowing the gap between the resources devoted to their men’s and women’s sides. Barcelona are aiming to follow a similar model, but are currently far earlier in their timeline.

Lyon’s model is being followed from across the channel in England, as shown by the growth of the Women’s Super League over the last decade. Clubs with significant financial resources, such as Arsenal, Manchester City, and Chelsea, are leading the way in terms of investment in their women’s sides. But the Football Association, England’s governing body for the sport, also deserves credit. The FA—which banned the women’s game for 50 years, almost a century ago—has done a remarkable job of creating a brand for the WSL in the same way it did for the men’s Premier League. It’s also brought in corporate partners that have provided clubs with fewer excuses not to invest in their women’s sides. When the WSL season begins this weekend, nine of the league’s 12 sides will have men’s teams in the Premier League, compared to five teams in 2018. Manchester United Women were founded just two years ago, yet, on the eve of their second season in the top flight, are expected to bring in World Cup winners Tobin Heath and Christen Press.

The FA no doubt has kept a watchful eye over Lyon’s rise to the top of the continental game, but it does not want the WSL to fall into the same trap as the Division 1 Féminine by knowing each season’s winner before a ball has been kicked. And so far, so good, with four sides winning the last 10 titles and none managing to retain it since Liverpool went back-to-back in 2013-14.

Wolfsburg is another success story. They’ve dominated in Germany since the club increased its investment in the women’s team at the beginning of the 2010s. However, it’s hard to imagine them having a better chance to win the Champions League anytime soon. The club from Lower Saxony still operates at a significant disadvantage compared to Lyon, despite winning as many major trophies this season as Wolfsburg’s men have in their 74-year existence. The talent exodus is already underway: Gunnarsdóttir is gone, and Harder, the team’s top scorer in two of the last three seasons, is joining Chelsea for what is a record fee in the women’s game. Her arrival coincides with a host of the world’s best players arriving in England, as the WSL stakes its claim for being the world’s premier destination. Lyon’s Bronze and Alex Greenwood will return to England, rumored to be joining Rose Lavelle, Sam Mewis, and Chloe Kelly at Manchester City.

The completion of the Champions League was an achievement in itself, as the pandemic shut down most European women’s leagues: Of the eight clubs that headed to Basque country to complete the tournament’s revised format, only the German representatives, Bayern and Wolfsburg, had completed their domestic seasons. France, England, Scotland, and Spain all canceled their league campaigns due to the coronavirus.

It was a huge blow to European women’s soccer, which had built up momentum over the past year. There was a legitimate fear that the work done to grow the game’s stature had been checked. As major clubs announced layoffs and backtracked on furlough schemes, it seemed all too likely that the women’s game would be hit the hardest. As Liverpool spent over a million dollars on fireworks to celebrate their men’s Premier League title, their women’s team—formerly one of England’s dominant forces—were relegated from the Women’s Super League, following a turbulent season of underfunding that resulted in an exodus of players.

However, with new domestic seasons starting soon, some of those concerns have abated thanks to some smart decisions by those at the top of the women’s game. UEFA used last year’s Champions League final weekend in Budapest to announce a new multiyear deal with Visa, to support women’s soccer in Europe. On the eve of this year’s final, a sponsorship deal with Pepsi was announced for both the Women’s Euros and Champions League, including financial commitments to the game throughout Europe. The deal coincides with a restructuring of the Champions League: A group stage will be implemented in 2021-22, so qualifying teams will play more games. More sides will also qualify—the WSL will receive three places—hopefully resulting in wider distribution of the new wealth.

In the United States, it will be interesting to see whether the NWSL can build on a successful showing from its condensed Challenge Cup format. They were the first league to resume play in the U.S. after the shutdown, and the games were well received in terms of TV ratings and sporting drama, as three of the top four seeds were eliminated at the first knockout stage. The coverage has generated more interest in the women’s game in the U.S., as NC Courage played Portland Thorns in a game viewed by an audience 201 percent larger than the previous best for an NWSL game. It was a positive conclusion to what threatened to be a tricky moment for women’s soccer in the U.S. after last year’s World Cup win, a feeling Jessica Luther expressed on Meg Linehan’s Full Time podcast. Just this week, it was announced that both the NWSL and WSL will be shown on major broadcasters from this weekend onward.

While the WSL is undoubtedly the place to be currently, it’s an exciting time for the women’s game in Europe as a whole. Lyon—despite a number of departures—will most likely remain favorites to complete a sixth Champions League in a row next year, but they may face stronger competition, most notably from Manchester City and Chelsea. After all, with new investment and new signings, what better motivation to win Europe’s top club competition than to put an end to one of the most dynastic periods that the game—men’s or women’s—has ever seen?