Does Tennis Owe Its Players a Living?

Its top stars make millions; its lower-seeded players are often in debt. A global pandemic has only exacerbated the sport’s inequality. Can average tennis players afford to keep competing—and can the sport survive without them?The 2019 U.S. Open was a breakout moment for American professional doubles player Hunter Reese. The Georgia native had played the event once before, five years earlier, when he gained automatic entry by winning the NCAA doubles championship as a junior at the University of Tennessee. In the first round of the 2014 Open, he and his partner faced the 10th-seeded team of Michael Llodra and Nicolas Mahut, Frenchmen with a wealth of Grand Slam and Davis Cup experience. Reese and his partner lost, 6-4, 6-1. It was by no means an embarrassing performance, and “I was sort of just happy to be there,” Reese said. “It’s not like we went in thinking we were going to win the tournament.”

But last year, when Reese returned to the Open, he was a doubles’ tour veteran, ranked just outside the top 100 in the world, and he came in with higher expectations. He’d teamed up with Evan King, a former University of Michigan star, and they’d had success on the Challenger Tour the past couple of years. (The Challengers are men’s professional tennis’s version of Triple-A baseball—a feeder system to the bigger tournaments one sees on television—and there’s a comparable circuit for women called the 125K series.)

Across the net from Reese and King were two objectively better tennis players. Australia’s John Millman has been ranked as high as no. 33 in the world in singles, and hard-serving Alexander Bublik had cracked the top 50—but they’d never played together.

When Reese and King squeaked out the match by winning a third-set tiebreaker, their celebration was euphoric. It was a career milestone—winning a round at a Grand Slam—and though they went on to lose in the next round to the eighth seeds and eventual finalists, Reese cashed the largest check of his career—$15,000. That single payment represents roughly one-sixth of his career earnings.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, players at Reese’s level found it difficult to earn a living. They have to cover flights, coaching, and other expenses out of pocket, with prize money that’s far less than at Grand Slam events. “Challengers now are at least covering hotels, but only until you lose at the tournament, and you usually stick around to practice for the next week if you go out early,” said Vahid Mirzadeh, a onetime top-200 player who walked away from the doubles tour when he was only 28. “You’re looking at about $1,000 a week in expenses, including airfare.”

Doubles players also have to split prize money with a partner. But making it in singles is also difficult. A couple of years ago, Thai-Son Kwiatkowski, who won the NCAA singles championship in 2017 before turning pro, tweeted details about his 2018 tax returns: “Net loss of 63k and 100k loans payable.”

As it has with other industries, the pandemic has illuminated tennis’s foundational problems. In the United States, professional baseball, basketball, golf, and women’s soccer have relaunched with mixed success, but tennis is an international sport with no single ruling body. Instead, there are fiefdoms that are loosely intertwined but often act independently: the Grand Slams (Australian Open, French Open, Australian Open, and Wimbledon), the Women’s Tennis Association, the (men’s) Association of Tennis Professionals, and the International Tennis Federation, among others. Wimbledon canceled its tournament this year, while the French Open unilaterally postponed until the fall, forcing lesser events to scramble. The U.S. Open, starting this week, decided to proceed with a fanless experience, emulating the NBA’s Orlando bubble. Meanwhile, players and others have organized exhibition events, none more notable than world no. 1 Novak Djokovic’s disastrous Adria Tour, which featured full stands of maskless fans, a Matrix: Reloaded–style indoors afterparty, and an ignominious shutdown after multiple players, including Djokovic, tested positive for the coronavirus.

In April, in a tweet heard round the tennis world, Roger Federer suggested merging the women’s and men’s governing bodies—the Women’s Tennis Association and the Association of Tennis Professionals—which control much of the professional tour outside of the Grand Slams. There were some shouts of approval and murmurs of skepticism, but no serious action has been taken. Last week, Djokovic resigned as ATP Player Council president and announced that he and other men’s players were forming a competing body, the Professional Tennis Players Association. But it’s unclear what exactly the PTPA will be—Djokovic said it isn’t a union—and Federer and Rafael Nadal quickly indicated they wouldn’t be joining the breakaway body.

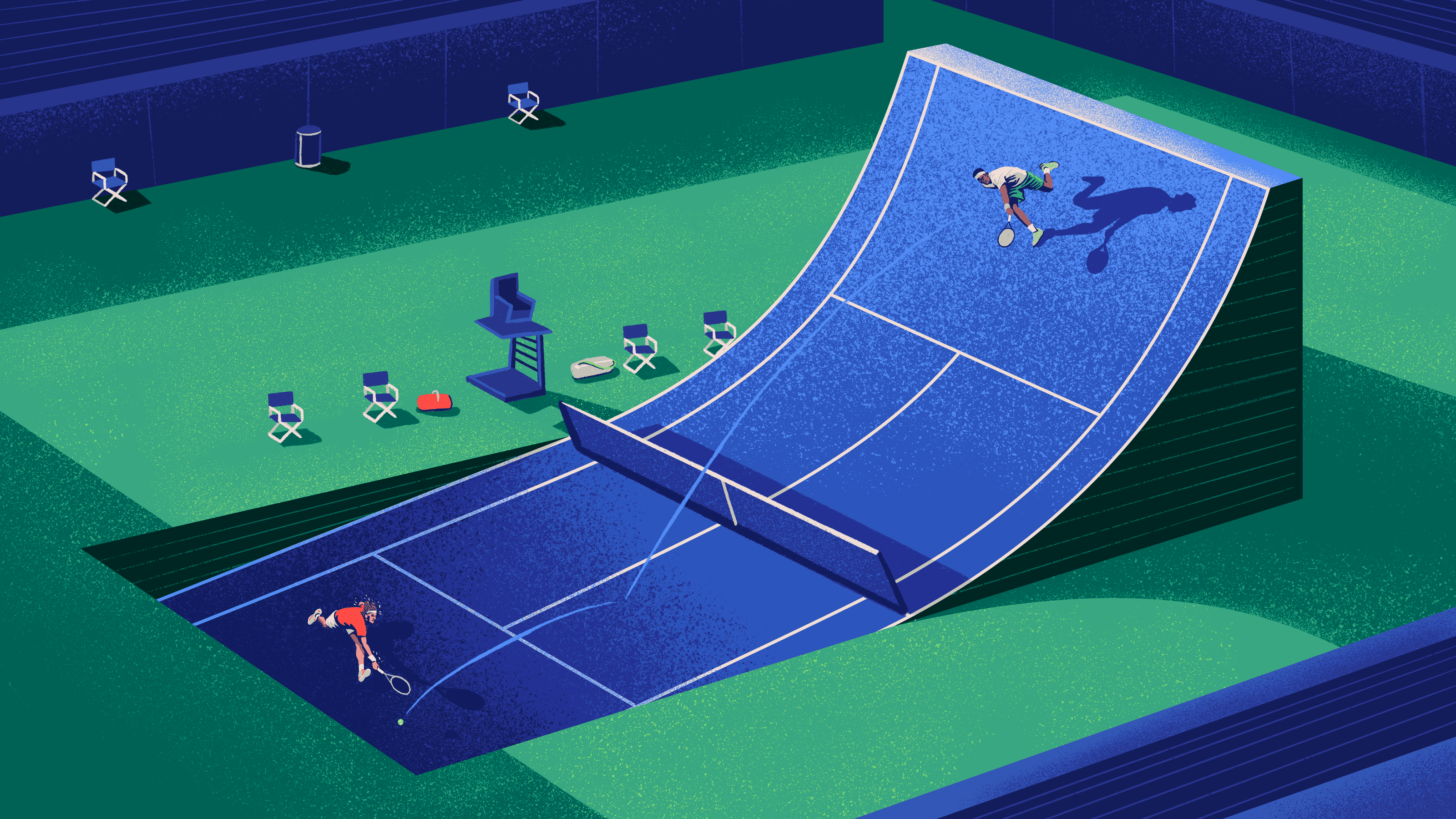

Meanwhile, there are many in the sport who would say that what’s needed isn’t just a bureaucratic shakeup but serious financial reform. Federer, Djokovic, Nadal, the Williams sisters, and the rest of the sport’s über-elite will be fine missing a few months of tournament paychecks, having accumulated generational wealth. But unlike unionized sports such as baseball, football, basketball, and hockey, in tennis there’s no guaranteed minimum salary. Many players outside the top 100 lose money playing the sport.

Reese told me that to make a comfortable living in normal pre-pandemic times, a player needed to be ranked in the top 100 in singles or top 70 in doubles—the level where a player is generally guaranteed entrance into the Grand Slams, which each feature 128 singles players and 64 doubles teams. Others say those benchmarks may be too optimistic. “You have to be in the top 50 to be able to put any money into savings,” Jamie Loeb, a 25-year-old professional, told me. Loeb, a New York native, has been ranked as high as 132 in women’s singles in the world but considered leaving the sport last year.

When I recently spoke to Kwiatkowski, who’s now ranked 187 in the world in singles, he posed an existential question: “Do we want, as a sport, for the top 250 men’s and women’s players to make a decent living? That’s something the sport needs to decide.” And such a reckoning is long overdue, Reese said. “[An] overhaul is what’s needed in tennis, with or without COVID.”

Reese grew up outside Atlanta. His parents were recreational players and introduced the sport to Hunter and his younger brother, Jaryd, who went on to play at Jacksonville State. The boys played a lot of sports. “I thought I was going to be a pro baseball player when I was a kid,” Hunter said.

But by high school—unlike a lot of top juniors, Hunter wasn’t homeschooled—he had to choose between tennis and baseball since both were spring sports. “I remember he lost one tournament match to someone he thought he should have beat,” Hunter’s mother, Kennedy Reese, recalled. “I said, ‘Hunter, that kid plays two hours every day and you play two hours a week.’”

Reese began training at a local academy run by Stephen Diaz, who had played at Auburn University, and began competing at national tournaments. According to the Tennis Recruiting Network he was the top high school senior in Georgia and ranked as high as 11th nationally. He accepted an offer to play at Tennessee, where he was thrust into the starting lineup after two upperclassmen decided to turn pro. (One of them, Tennys Sandgren, made it to this year’s Australian Open quarterfinal, losing to Roger Federer despite having several match points.)

Reese sometimes played the no. 1 singles position for the Volunteers, but it was in doubles, paired with his Latvian classmate Mikelis Libietis, where he shined. “They complemented each other well,” said Chris Woodruff, Tennessee’s head coach, who was once ranked as high as 29 in the world in singles. At 6-foot-4, Libietis has a big serve and crushing forehand, while Reese, 5 inches shorter, is an aggressive volleyer with a laser two-handed backhand. “Hunter’s greatest attribute, unequivocally, is his competitive spirit,” Woodruff said. “I wouldn’t quite categorize him as an overachiever, but I wouldn’t say he has loads of God-given ability, either. He’s had to work for everything he has.”

Doubles is an afterthought for the world’s best players—except the Williams sisters, who have competed much more often in doubles than Federer, Nadal, Naomi Osaka, or the recently retired Maria Sharapova. Doubles specialists like Reese face hurdles that his single peers don’t. While singles tournaments reserve spots for lower-ranked players who compete in a pre-event to make the main draw, there are no qualifying events for doubles. Prize money is lower too.

Reese won his first professional doubles match at a 2014 Futures event in Illinois, earning $64. (Futures are the lowest level of professional tennis, below Challengers and akin to Single-A baseball.) A year later, partnered with Libietis, he pocketed $180 for reaching the finals of a Futures event in Lithuania. Graduating to the Challenger tour upped the payouts, but not by much. For winning four consecutive matches and the championship trophy at a 2018 Challenger in Cary, North Carolina, Reese earned $1,550, or roughly one-tenth of his paycheck after a single victory at the U.S. Open.

To pay his expenses for his first couple of years as a professional, Reese was subsidized by his parents. “He built up a nest egg,” said Kennedy Reese. But even before the pandemic, she’d noticed his bank balance was shrinking. “We said it’d be OK if he needs a little more financial support, but it can’t be unending.”

Reese’s last tournament before the tour shuttered in early March was a Challenger event in Indian Wells, a precursor to the larger, prestigious ATP event in the same location, which was canceled. He lost in the quarterfinal for a $960 payout.

Since then, players at all levels have scrambled to play wherever they could—often in unlikely venues. My Swarthmore College teammate’s family, the Emkeys, hosted an early August socially distanced event at their home court in Reading, Pennsylvania, featuring Kwiatkowski and Denis Kudla, who’s been ranked as high as 53 in the world. Kudla won the backyard event and walked away with $4,000—a far cry from the $163,000 he took home after losing to Djokovic in the third round of last year’s U.S. Open but a welcome check and rare competitive opportunity during the pandemic. Reese has played similar exhibition events in Florida and Georgia, earning a few thousand dollars.

Like other contract workers, many tennis players have filed for unemployment insurance. Others have taken second jobs. In May, Jamie Loeb began working as a sales representative for Har-Tru, the maker of the “green clay” courts that can be found at tennis clubs and parks throughout the country. She told me she’s also working to complete her undergraduate degree online through the University of North Carolina. Loeb returned to action in early August in Lexington, Kentucky, winning a singles and doubles match and earning $2,675. But she didn’t know when she’d be able to compete again. “It looks like all the smaller tournaments are in Europe,” she said.

Meanwhile, several top players pulled out of the U.S. Open, including current women’s no. 1 Ash Barty and defending champions Rafael Nadal and Bianca Andreescu. Nick Kyrgios, a top-five talent currently ranked 40th in the world, also withdrew, citing coronavirus concerns. The staid tennis cognoscenti have frowned at Kyrgios’s on-court antics over the years, but he’s emerged as the sport’s unrepentant voice of reason during the pandemic and publicly reprimanded Djokovic, Alexander Zverev, and others for endangering lives with their maskless frolics.

Reese hoped to play the U.S. Open this year. “It’s a huge opportunity for my career,” he said. “That’s selfish of me perhaps, with the coronavirus, but that’s the reality of where I am.” But Reese didn’t make it to Queens. When it announced it would proceed with a fanless event, the United States Tennis Association, which runs the Open, said it would take steps to limit the number of people on the premises. Players would be allowed to bring only one guest each to the event—not the usual retinue of coaches, physiotherapists, and family members that usually accompanies top players. It also said it was cutting wheelchair competitions, mixed doubles, and the legends and junior events as well as eliminating qualifying events for men’s and women’s singles. The USTA also cut the men’s and women’s doubles fields in half.

The organization faced a fierce backlash for cutting the wheelchair events and quickly reversed itself. It also caved to the demands of top players accustomed to their traveling teams and said each player could invite three guests. For Reese, it was a slap in the face. “I understand that the tournament wants to keep numbers down for safety,” he said. “But then the USTA changed the guests from one to three while still cutting the doubles fields and you realize it’s completely arbitrary.” Lower-ranked players—players who can’t afford full-time coaches and physiotherapists themselves—were sacrificed so that Djokovic could get a massage. (Djokovic also eschewed the player hotel and instead rented a nearby private home; his movements will be monitored by a USTA security guard, paid for by Djokovic.)

Another gripe is that as the tour reboots, it’s offering high-level ATP Masters events—the U.S. Open and French Open—while offering few Challenger and Future events. Players who qualify for the top events will amass rankings points and money unavailable to lower-ranked players, widening the gap between the sport’s haves and have-nots. The first three Challengers scheduled were in Europe, out of the reach of North American players during the pandemic. Just as Loeb complained about the lack of women’s tournaments in the United States, Peter Polansky, a Canadian player, tweeted: “How is it fair for anyone outside of EU who need to jump through fire to play 100k challengers?”

But Kwiatkoski empathized with the tour organizers operating during COVID times. “How can they operate Challengers in a safe way?” he wondered. Challengers and Futures aren’t “bringing in a lot of money,” he continued, “so to add the cost of testing on site and extra precautionary safety measures doesn’t make financial sense.” It’s the sport’s least-remunerated players who are losing out on tennis’s reboot.

Most top players aren’t unsympathetic to the plight of their lower-ranked peers. In a recent Instagram Live chat with Djokovic, three-time Grand Slam champion Stan Wawrinka noted, “To be 250 in the world in tennis is already amazing. And they barely can live right now, so what is the option that can help them to at least survive the coronavirus until we can start to play again?”

It’s a perennial, if unresolved, discussion in the sport. In the 1980s there was a proposal to shift player earnings from the top toward lower-ranked players. But it went nowhere. “The average player wants socialism, a welfare tennis state,” said Jack Kramer, the former world no. 1 player who was a driving force behind the once-amateur sport’s shift to the modern professional era and died in 2009. But, Kramer continued, “the big stars and their agents wanted to freelance like movie stars.”

Djokovic has proposed pooling some funds from the top players to be distributed to lower-ranked players, and in his chat with Wawrinka, the world no. 1 called for long-term reforms that would redistribute money away from the sport’s stars. Dominic Thiem, who lost to Djokovic in an epic five-setter in the final of this year’s Australian Open, publicly disagreed. “I’ve seen players on the … tour who don’t commit to the sport 100 percent,” he said. “Many of them are quite unprofessional. I don’t see why I should give them money.”

And while Thiem may seem heartless, rare is the capitalist industry where top earners gladly distribute their earnings to the less fortunate. Change is also unlikely to come from the sport’s top bureaucrats, many of whom haven’t taken a pay cut themselves. “The CEO of the ATP is making a million dollars a year and doesn’t take a pay cut,” Reese pointed out, “while every player on tour has seen their income go to zero.”

The USTA declined to speak with me about its preparations for the U.S. Open or tennis reform. But I did talk to two men, longtime rivals, who have helped shape the professional game for the past four decades. Donald Dell, a former professional player and agent who represented Arthur Ashe and Tracy Austin among many other notable clients, cofounded the ATP in 1972 with Kramer and Cliff Drysdale. Bob Kain built up super-agency IMG’s formidable tennis division and represented Billie Jean King, Bjorn Borg, Pete Sampras, and Andre Agassi. But they didn’t only represent players. Dell also ran the Washington Citi Open, a U.S. Open lead-up event. And Kain has represented Wimbledon, the Australian Open, the ATP, and WTA in various capacities.

Both men pushed back against the idea that the sport was failing its lower-ranked players. “I personally don’t think anybody owes anything,” Dell said. “I think you earn it. You can’t say, ‘Jeez, the game owes me that.’ I don’t buy that.” Kain agreed and told me, “I don’t think tennis is obliged to keep people employed if they’re not good enough.”

Tennis is doing its best to help players during these uncertain times, Dell said. He cited Wimbledon’s decision to pay $13 million to players even though it canceled this year’s tournament. “That’s phenomenally generous,” he said. “No one’s done that before.” And he praised the U.S. Open’s decision to reduce its prize money by only 5 percent while forgoing $140 million in ticket sales and additional millions in sponsorships and concessions receipts.

Players see it differently. Reese said the fact that the U.S. Open is paying 95 percent of its usual prize money while expecting a revenue loss of more than 50 percent just shows how stingy the USTA has been in normal years. (The U.S. Open, the only major tournament for which public financial information is available, distributes only between 12 percent and 15 percent of tournament revenue to players.)

Without unionizing, which has always proved difficult for individual, international sports, it’s difficult to see how players could win the reforms they’re seeking. Reese said he’d like to see prize money, which roughly doubles each round of a tournament, distributed more to the earlier rounds. If Djokovic, the heavy favorite, wins the U.S. Open, does he really need a check for $3 million? Wouldn’t $2 million suffice? Brad Gilbert—a thoughtful, ubiquitous presence in the game, having been a top player, coach, commentator, and now podcaster—told me he’d like to see more prize money at Challenger and Future events. He favors limiting the amount of these events—“Sometimes you have five to seven Challengers and 10 to 12 Futures in the same week”—and expanding the prize money. Kwiatkowski advocates for a similar approach, saying some revenue from the bigger events should be pooled to increase payouts for the minor leagues.

“Do we want a guy playing Futures to be putting hundreds of thousands of dollars away?” Kwiatkowski asked rhetorically. “No. That’s not what we’re asking for. But if you’re a Futures player you need to be paid a livable wage for sure, and the prize money has been the same for two decades.”

Unionized team sports have done this with league-mandated minimum wages. Reese said that players have talked casually about the idea of minimum salaries, though he added, “I don’t know what that would look like.” Gilbert was skeptical. “I’ve never been at any meetings where that idea was discussed,” he said. However, the tour recently announced a one-off $6 million player relief fund for lower-ranked players, drawing on contributions from the Grand Slams, ITF, ATP, and WTA. Logistically, at least, it’s a model for a more permanent form of minimum salary.

Dell, an advocate for an ATP-WTA merger, said now is not the time for major reforms as the sport gingerly returns during a health crisis. “None of that’s going to happen right now,” he said. “Everybody’s struggling to get back on tour.”

Reese doesn’t know when he’ll next compete, given that Challengers in the United States are canceled at least until the end of September. Before the pandemic, he and his similarly ranked peers would get together and “talk shit about the USTA and ATP,” resigned to feeling that “we don’t matter and let’s just grind through it and hopefully we’ll make it.” They’d even laugh about it in solidarity.

But no longer. For Reese, the past few months have crystallized his feelings about the sport’s indignities for lower-ranked players. “It’s like, ‘Dang, we really don’t matter at all. We don’t matter at all,’” he said. “Hopefully something changes soon.”

Paul Wachter has written for The New York Times Magazine, Harper’s, Grantland, and other publications.