On October 7, Dodgers center fielder and 2019 NL MVP Cody Bellinger stole a home run from Padres shortstop and 2020 NL MVP contender Fernando Tatis Jr. In the top of the seventh inning of NLDS Game 2, Bellinger prevented a deep drive from flying over the outfield fence to the left of the 407-foot sign at Globe Field, squelching a San Diego threat. It wasn’t the most difficult or acrobatic catch of the postseason—Manuel Margot’s over-the-railing grab in the ALCS takes top honors so far—but it may have been the most momentous. With a Padres runner on second and the Dodgers clinging to a 4-3 lead, Tatis represented the go-ahead run. Bellinger’s pivotal leap preserved that slim margin in a game that the Dodgers ended up winning 6-5.

Bellinger’s catch, and the Dodgers’ victory, were significant for another reason: They snapped a 19-game winning streak for teams that had outhomered their opponents in the 2020 postseason.

In this case, the exception helped prove the rule. Although the Dodgers won with fewer homers, they barely scraped by, and their victory required a spectacular catch. The win expectancy swing when Bellinger brought the ball back hammered home how decisive dingers can be. The difference between a long out and a long ball was probably the difference between a loss and a win: If Tatis’s smash had carried a few feet farther, the Padres likely would have evened the series.

But Bellinger’s streak-stopping catch didn’t kill the fun fact. The record of teams that have hit more homers has become the most commonly cited statistic this month, updated on Twitter after each game and mentioned on MLB broadcasts almost as often as shadows on the field. Through Wednesday’s games, postseason teams were 26-2 when they outhomered their opponent; beyond the Bellinger game, the only deviation from the trend was ALCS Game 3, in which the Astros outhomered the Rays 2-0 but lost 5-2.

In a sense, it’s strange that this stat has been ubiquitous. On the surface, it almost seems self-evident: Of course teams that have hit more homers have fared well. As the MLB rulebook succinctly says, “The objective of each team is to win by scoring more runs than the opponent.” Home runs are, by definition, run-scoring plays; “runs” is right there in the name. If we knew nothing about a game except that one team hit more homers, it would make sense to surmise that the more prolific homer hitters won.

Despite the seemingly unsurprising and borderline axiomatic takeaway that hitting homers is, all else being equal, better than not hitting homers, the stat keeps circulating for three reasons. The first is that so many fans and media members insist otherwise. Just as basketball fans fret about 3-pointers in the playoffs and football fans worry about being dependent on passing, baseball pundits have professed that home-run reliance is October kryptonite for decades, despite all evidence to the contrary. Granted, while hitting more homers is a great way to win, the teams that profit from the long ball in October aren’t always the ones that did so all season; lately, a low regular-season strikeout rate has been a better predictor of postseason success, though contact and dingers aren’t mutually exclusive.

To re-check the relationship between regular-season home-run reliance and postseason scoring, I sorted all of the pre-2020 playoff teams from the wild card era by the percentage of regular-season runs they scored on home runs, then split them into two groups: the less homer-reliant half and the more homer-reliant half. Teams from the group that was less reliant on the long ball collectively scored 15.4 percent fewer runs per game in the postseason than they did during the regular season. Teams from the group that was more reliant on the long ball collectively scored 16.8 percent fewer runs per game in the postseason than they did during the regular season. In other words, teams from the two groups suffered essentially the same postseason penalty. In addition, the more homer-reliant teams were better to begin with, plating about a quarter run more per game during the regular season than the less homer-reliant teams. The former continued to outscore the latter in the postseason by about half that amount.

Maybe hitting homers is viewed as less virtuous than manufacturing runs; maybe some observers mistakenly assume that homers are hit on mistake pitches that will disappear in the postseason, or maybe all-or-nothing lineups look extra impotent when they aren’t launching homers, leaving a lasting impression of playoff futility in the minds of defeated fans. Whatever the reasons for anti-long-ball bias, many national baseball broadcasters seem determined to denigrate the dinger, celebrate small ball, and urge teams to bring back sacrifice bunts. When October TV viewers are as likely to hear that home runs are rally killers as they are to be told that it’s good to go deep, a stat that says slugging is the way to win in the postseason serves a useful corrective.

The second reason why the stat is inescapable is that home runs really do take on an outsized importance in October. (More on that in a moment.) The third is that 26-2 sounds extreme, even to those who accept that hitting home runs helps. And while hitting more homers has always been beneficial to teams, the low-contact, homer-heavy brand of baseball being played today is especially likely to lead to uneven round-tripper totals and games that go the slugging side’s way.

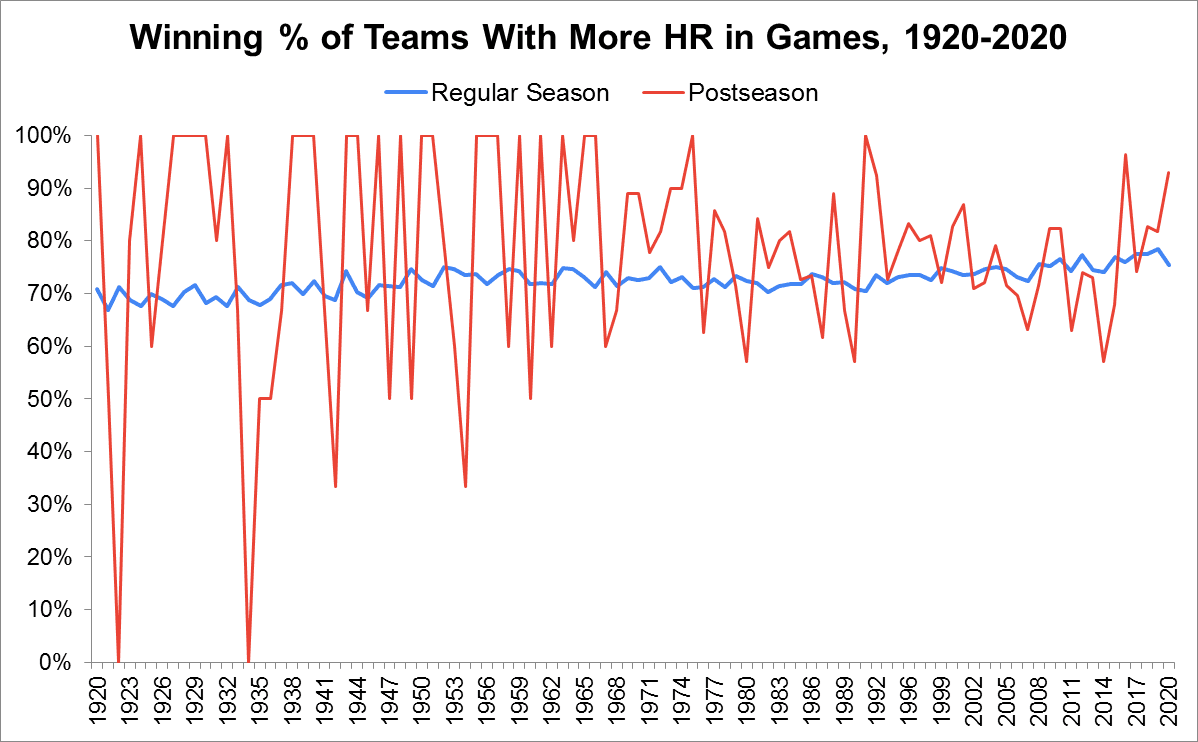

The graph below shows the winning percentage of teams that outhomered their opponent in each regular season and postseason since the start of the live ball era in 1920.

The red line, which represents the year-by-year postseason winning percentages of teams that outhomered their opponents, fluctuates wildly, reflecting the small sample sizes inherent to October (particularly prior to the addition of the League Championship Series in 1969). This postseason’s 26-2 mark to date (a .929 winning percentage) trails only 2016’s 27-1 (.964) among postseasons in the wild card era.

The much more stable blue line, which represents the annual regular-season winning percentages of teams that outhomered their opponents, demonstrates that hitting more homers has always been a reliable indicator of success, even during the days of Babe Ruth and Ty Cobb. “Ball go far, team go far,” as the baseball writer Joe Sheehan puts it, is not a new reality. If you squint, though, you can see a slight slope up in that line over time. It’s easier to tell that today’s teams that hold the home run high ground win more often than yesteryear’s if we break this down by decade.

A century ago, teams that outhomered their opponents won almost 70 percent of the time. In the 2010s, they won a little more than 76 percent of the time. (During the 2020 regular season, their winning percentage stood at .754.) Why has hitting more homers become a surer sign of success? Well, for one thing, home runs account for a far higher percentage of scoring than they used to.

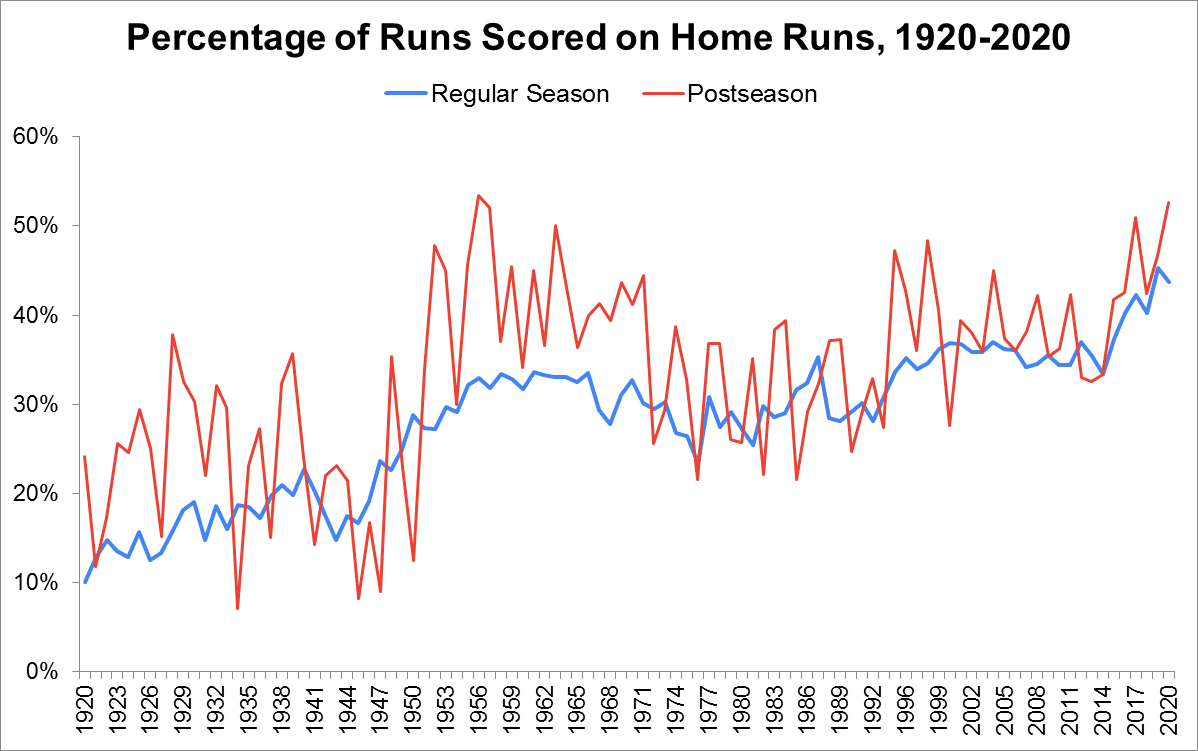

In the waning years of the deadball era, fewer than 10 percent of runs scored on homers. In 1920, that percentage reached double digits, and it’s more than quadrupled since then. In 2015, the first season of the ongoing juiced ball era, the percentage of runs scored on homers—what Sheehan dubbed the “Guillén number” when he used it to illustrate that Ozzie Guillén’s 2005 White Sox weren’t the small-ball squad some media members had made them out to be—reached 40 percent. The Guillén number peaked at 45.2 percent in 2019, then dropped to 43.7 percent in 2020 as a slightly less aerodynamic baseball moderately reduced home-run rates.

The current conjunction of historically high home-run and strikeout rates has crowded out every other type of on-base event, making it more difficult to score without hitting the ball over the wall. It stands to reason, then, that the team that hits more homers would win more often; it’s harder for the team that gets outhomered to make up for that deficit in other ways.

Notice, too, that the red line in the graph above (postseason Guillén number) has historically hovered above the blue line (regular-season Guillén number). In the playoffs, both runs per game and home runs per game typically decrease, but the latter tails off less. Thus, the percentage of runs scored on homers spikes: In the wild card era, the cumulative postseason Guillén number (40.5 percent) has eclipsed the cumulative regular-season Guillén number (36.6 percent) by a little less than four percentage points. In the six seasons of the juiced ball era, the gap has been even bigger (46.5 percent versus 41.4 percent). This postseason’s Guillén number of 52.7 percent is the highest since 1956, when the Yankees and the Dodgers, who were home-run reliant by the standards of their day, combined to score 31 of the 58 runs in their seven-game World Series (53.4 percent) on 15 homers, 12 of which were hit by the victorious Yankees (and six of which left the bats of Yogi Berra and Mickey Mantle).

The Guillén number generally rises in October because postseason play brings different conditions: more relievers, speedier fastballs, more strikeouts, superior defenses, and so on. All of those changes favor short-sequence offense (scoring via a single swing) over extended rallies that are even harder to prolong in the playoffs. Consequently, teams that outhomer their opponents dominate to an even greater degree in October. Dating back to 1920, teams in the regular season have amassed a combined .730 winning percentage when they’ve outhomered their opponents. In the playoffs, that combined mark is .774. If we focus on 2015-20, those figures rise to .771 and .825, respectively.

One additional development has made home runs much more salient as the modern means of success. Up to this point, we’ve been dwelling on what happens in games when one team outhomers another, but we’ve skipped over another possible outcome: neither team outhomering the other. (It’s true that teams that have hit more homers in games this postseason have gone 26-2, but that leaves 12 other contests in which the two teams’ homer totals were tied.) In earlier eras, far fewer homers were hit, so it was much more common for two teams to finish with the same home-run count in any given game: Often, both would go homerless. Now that the ball is flying and batters are angling up, lopsided tallies are less unusual, as the Dodgers demonstrated when they launched five homers to Atlanta’s one in NLCS Game 3.

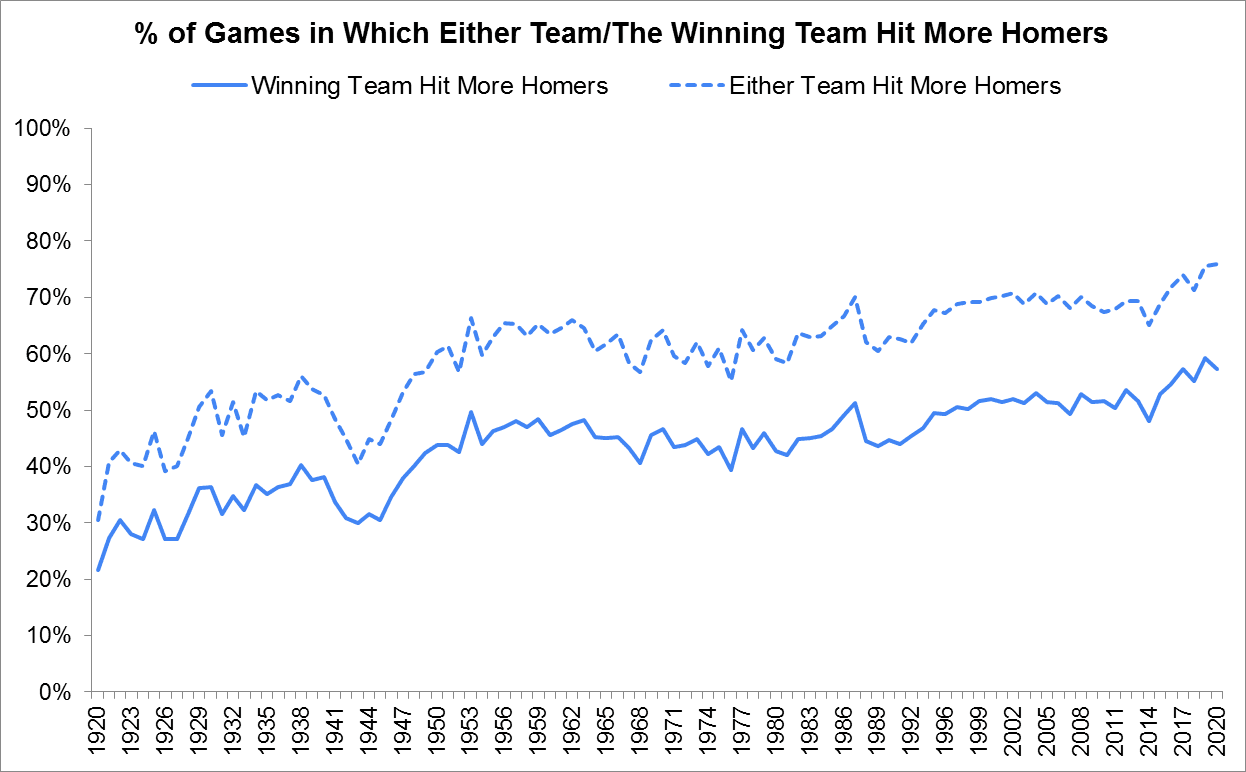

The graph below, which also goes back to 1920, shows the annual percentages of all regular-season games in which the two teams produced different home-run totals and, separately, in which the team that hit more homers won.

In the 1920 regular season, only a little more than 30 percent of games ended with one team outhomering the other, and a little more than 20 percent of games ended with a team that hit more homers triumphant. In the 2020 regular season, more than three-quarters of games ended with one team outhomering the other, and almost 60 percent of games ended with a team that hit more homers triumphant. Both of those rates tend to be even more elevated in October. So it’s not just that teams are winning more often when they outhomer their opponents; it’s also that it’s much more common for one team to outhomer another. Hence this postseason’s omnipresent stat.

As I’ve noted before, the playoffs exacerbate baseball’s least fan-friendly traits, delivering slower and longer games, more pitching changes, and fewer balls in play. This postseason is no exception: After setting a record regular-season strikeout rate for a 15th consecutive season, hitters have seen their strikeout rates soar even higher in the playoffs. The home-run rate has risen too, possibly because of another change in the ball’s behavior. The result is a static scoring environment that’s a lot lighter on baserunning and fielding than baseball has been in the past. Many of this month’s games have been inning after inning of empty bases and fruitless, rally-ending whiffs with men on, interspersed with occasional lasers that have left the park and anointed a winner.

At various points in this postseason, the prospect of scoring a run without hitting a homer has seemed incredibly remote. In ALDS Game 5, for instance, the Rays and Yankees entered the eighth tied at one, with each team’s lone run attributable to a wall-scraping solo homer. As I watched a succession of overpowering pitchers mow down some of the best batters in the sport, I became convinced that the only way it would end was for someone else to hit a tie-breaking solo shot. (As base runners have grown scarcer, the solo homer has become by far the most common kind.) In the bottom of the eighth, Mike Brosseau obliged, and the Yankees were toast.

On an intellectual, logical level, I know it’s not impossible that the Rays or Yankees could have scored some other way. In the moment, though, that ending seemed inevitable. The pitchers were too talented for the hitters to hope for anything but one decisive swing (a formula for upsets). Game 5 was a classic because of the win-or-go-home stakes, the rivalry between the two teams, and the history between Brosseau and Aroldis Chapman, but a game with 24 combined strikeouts, six combined hits, and zero hits with a runner on base wouldn’t be as easy a sell on a sleepy day in May.

At present, May seems like a long way away. But postseason play is a preview of what regular-season baseball will look like before long if the causes of the sky-high strikeout and home-run rates are left unchecked. As of now, that future figures to be full of death by dinger. And while sacrifice bunts will always be boring, those homer-hating broadcasters are right about one thing: The game is more entertaining when there’s more than one way to win.

Thanks to Kenny Jackelen of Baseball-Reference and Robert Au of Baseball Prospectus for research assistance.