From 2009 to 2017, Clayton Kershaw lowered his career ERA in nine successive seasons, one of the longest such streaks of all time. The duration of the streak summed up the southpaw’s excellence: Even after winning three Cy Young awards—the latter two of which came in seasons with sub-2.00 ERAs—Kershaw continued to improve on his previous record. In each of the last three years of the streak, his mark to beat was below 2.50, and each time, he sailed smoothly under it. As I wrote at the start of the streak’s final season, “The lower the limbo bar falls, the better he gets at bending beneath.”

In 2018, Kershaw finally bumped into the bar. The lefty ace entered the year with a 2.36 career ERA, which rose to 2.39 after he finished the season with a *gasp* 2.73 ERA. That was still a top-10 figure among pitchers who threw as many innings, but it seemed to mark the passing of peak Kershaw: For the first time since 2010, he wasn’t an All-Star and didn’t receive a Cy Young vote. Last year, Kershaw’s ERA topped 3.00 (albeit barely) for the first time in any full season, and while he was an All-Star and appeared on a single Cy Young ballot, his stats, stuff, and reduced durability all pointed to a pitcher who was past his almost unparalleled prime. Every indicator—including Kershaw’s age—pointed toward additional decline.

It’s heartening, then, that the 32-year-old Kershaw halted his streak of increases in career ERA at just two seasons. The 60-game schedule and back stiffness that slightly delayed the lefty’s debut limited him to 10 starts, but in that third of a season or so, he produced a 2.16 ERA, which would have been low enough for him to limbo below where his career bar rested after 2017, let alone where it was two years later. Not only did Kershaw stop his slide this season, but he also turned back the clock, recovering some of the stuff he’d surrendered.

In 2020, Kershaw has beaten both Father Time and the Brewers, whom he held to three hits and no walks in an eight-inning, 13-strikeout, scoreless start in last week’s wild-card round—by Game Score, his best postseason outing ever. On Wednesday, he’ll take on another opponent, the Padres, who dropped NLDS Game 1 to the Dodgers on Tuesday and are trying to stop a streak of their own: 51 seasons without winning a World Series. Can Kershaw beat them too?

If he does, it will probably be because the Padres proved susceptible to Kershaw’s standard strategy, a more effective version of the sneak-attack tactics I outlined last year. As a general rule, Kershaw pounds the zone with fastballs on the first pitch and loads up on breaking balls after he’s ahead in the count. Many pitchers follow that script to a certain extent, but Kershaw embraces it more than most. Among the 150-plus starters who faced at least 100 hitters this season, Kershaw’s 70.1 percent four-seamer rate on the first pitch of plate appearances trailed only his teammate Walker Buehler’s. Similarly, only four starters threw first pitches in the strike zone at a higher rate than Kershaw’s 62 percent.

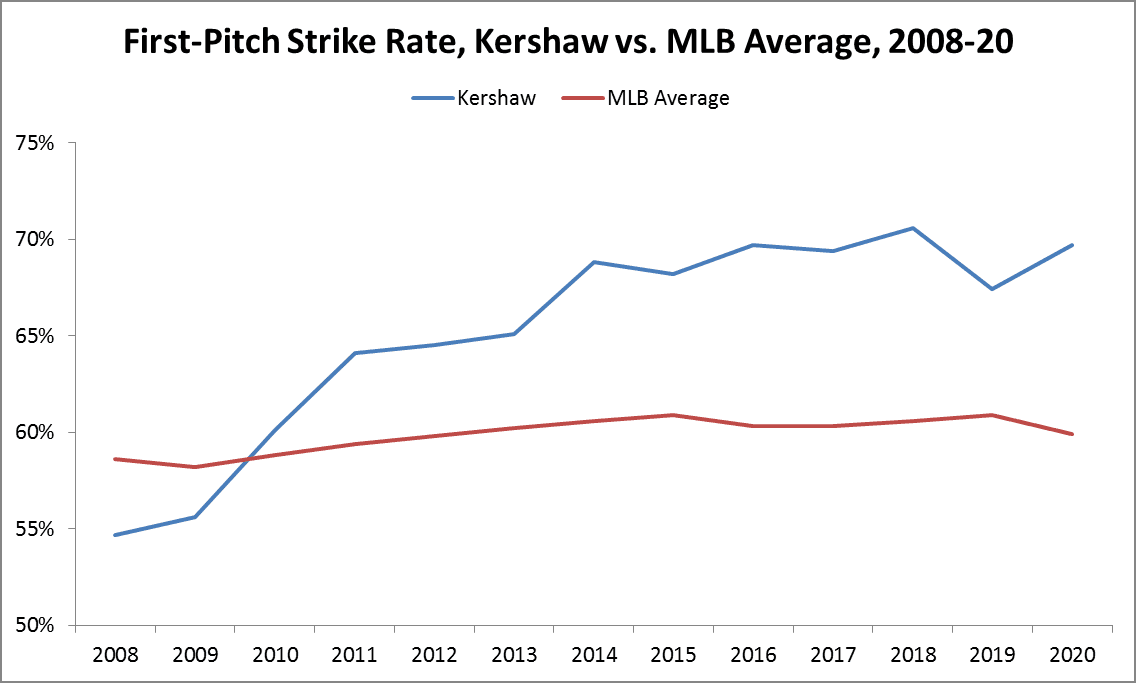

Hitters tend to be passive on the first pitch. This season, MLB batters swung at 42.1 percent of all first pitches in the strike zone, compared to 68.0 percent of pitches in the strike zone when they’re ahead in the count and 80.3 percent of pitches in the strike zone when they’re behind in the count. By filling the zone with first-pitch fastballs, Kershaw racks up first-pitch strikes, as he has for much of his career.

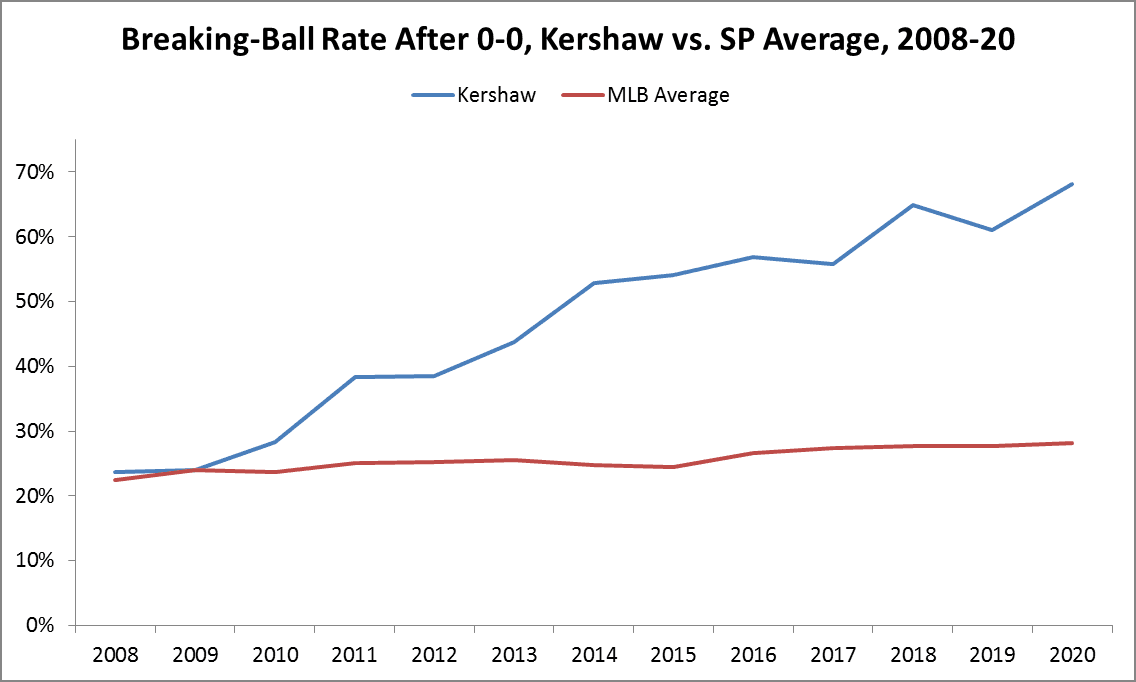

After the first pitch, Kershaw throws far more breaking balls than any other starter: 68.2 percent of his non-0-0 pitches this season were breaking balls, which put him almost 10 percentage points above any other starter and 40 percentage points above the 28.2 percent MLB average. (When the hitter is ahead in the count, Kershaw’s breaking-ball rate stands at 59.8 percent; when the hitter is behind, the rate rockets up to 75.2 percent.)

That approach represents a stark difference from a decade ago. In his first two seasons, Kershaw threw a roughly league-average number of breaking balls after the first pitch (about 24 percent). Since then, the league rate among starters has risen only slightly, while Kershaw’s has almost tripled.

Kershaw’s extreme pitch-type tendencies on the first pitch and thereafter have served him well this season: He gets ahead early and then presses his advantage. Of the 166 pitchers who threw at least 500 pitches in 2020, only four—Nathan Eovaldi, Charlie Morton, Yu Darvish, and Brandon Woodruff—kept batters behind in the count as often as Kershaw.

Kershaw has gravitated toward throwing more breaking balls over the course of his career for two reasons. First, he throws really good breaking balls. Second, his heater has steadily slowed. Whether because of his back woes or routine wear and tear, Kershaw had lost speed on his fastball in four consecutive seasons entering 2020. Although he regularly played down the importance of fastball speed, Kershaw also harbored hopes that it could come back. Sure enough, both his average four-seamer speed and his max four-seamer speed rebounded this year.

Maybe Kershaw regained a portion of that missing speed because of better health; maybe he picked up some insights during a brief offseason visit to Driveline Baseball, or maybe he benefited from a team-recommended alteration in training. “I just kind of threw everything at it,” Kershaw said in August. He hasn’t deviated from his reluctance to open up to the press about his process, but he has jettisoned an understandable but stubborn adherence to the practices that worked when he was younger, which bodes well for the rest of the future Hall of Famer’s career.

Whatever his secret, the results are rare. From 2008 to 2020, 78 pitchers who regularly threw a four-seam fastball amassed at least 50 innings as a starter in both their age-31 and age-32 seasons. Only 24 of them threw their fastball harder at 32 than they had at 31—and if anything, that overstates the likelihood of an uptick, because some 32-year-olds who saw their fastball speeds dip probably lost their rotation spots before they qualified for this sample. Only seven of the 78 added at least half a mile per hour, on average, and only four (including Kershaw and the wondrous Jacob deGrom in 2020) added at least a full tick. By partially righting his radar readings, Kershaw joined an exclusive club of starting pitchers in the pitch-tracking era who’ve regained any amount of four-seamer speed after losing speed in four straight seasons—and Kershaw’s decline before the recovery was the steepest of all.

Velocity Gains After Four Consecutive Seasons of Velocity Loss

Kershaw still doesn’t throw hard; his four-seamer speed is right around average for a left-handed starter. But average speed will suffice when paired with Kershaw’s command, spin, and movement. Among regular starters this season, only the seemingly foreign-substance-enhanced Trevor Bauer showed more vertical fastball movement than Kershaw, and only a few pitchers outpaced him in vertical slider or curveball break.

Plus, the primary payoff from the velocity boost may not be at the upper end of Kershaw’s fastball range, but at the lower end. From 2018 to 2020, Kershaw allowed a .414 wOBA on fastballs 90 mph or below, roughly equivalent to the overall production of MVP candidates José Ramírez or Ronald Acuña Jr. in 2020. He allowed only a .311 wOBA on fastballs 90 mph or above (approximately Pedro Severino or Travis Shaw in 2020). That’s a massive difference, and thanks to his speed resurgence this season, Kershaw has almost eliminated offerings in that slower, more vulnerable range. After throwing 21.2 percent of his four-seamers 90 mph or slower in 2018 and 37.1 percent of them that slow in 2019, only 3.8 percent fell within that speed span in 2020.

Although Kershaw’s ERA was somewhat suppressed by a luck-and-defense-aided .232 BABIP, his strikeout-minus-walk rate and average exit velocity allowed were his best since 2017, and he posted what would have been a career-high ground ball rate in a full season. Those improvements reinforce what we already knew: Velocity matters, even for all-time greats. The difference wasn’t solely reflected in fastball results: On a per-pitch basis, Kershaw’s slider was more valuable than it had been in any season since 2016, possibly because the slider also sped up slightly or because the fastball bounceback made it harder for hitters to differentiate the two.

In last week’s wild-card start, Kershaw’s four-seamer sat at 91.8 mph (topping out at 93.3), and 61 of his 93 pitches were sliders or curves. A current Kershaw approach yielded a vintage Kershaw line score: His 24 whiffs against Milwaukee were his most in a start since May 2016. The Brewers, however, were one of the worst-hitting playoff teams in recent seasons. The Padres are not.

In Kershaw’s lone start against San Diego this season, on September 14, he pitched into the seventh, striking out nine Padres without walking any. He left with the score tied at one but took the loss after reliever Pedro Báez—a serial saboteur of Kershaw’s postseason stat lines—allowed two inherited runners to score. The only run Kershaw coughed up directly came on a homer by Trent Grisham, which highlights one of the ways to beat 30-something Kershaw: Take him deep. Without the mid-to-upper-90s heat he used to have, Kershaw’s misses are prone to turning into Barrels and sometimes flying over the fence. The Padres, who trailed only the Dodgers, Braves, and White Sox in 2020 dingers, will be primed to prey on mistakes.

On the plus side, the Padres ranked 16th in MLB in first-pitch swing rate and 13th in first-pitch swing rate on pitches in the strike zone, so they don’t appear particularly likely to disrupt Kershaw’s first-pitch plans. (The Braves lead the majors in both categories, so Kershaw should beware of ambush swings if L.A. and Atlanta face off in the NLCS.) However, the Padres’ bats produced a major-league-leading .309 expected wOBA on breaking balls, which means Kershaw could be in trouble later in plate appearances.

As always in October, Kershaw’s tattered reputation as a postseason pitcher is riding on each outing.

Among the 129 pitchers with at least 50 career postseason innings pitched entering Tuesday, Kershaw’s postseason/regular-season ERA gap of 1.79 was the third-largest ever. None of the other October underperformers compiled a postseason workload nearly as large as that of Kershaw, who’s thrown the seventh-most postseason innings ever.

Biggest Gaps Between Postseason and Regular-Season ERA (Min. 50 Postseason IP)

Kershaw’s regular-season success in 2020 slightly widened that gap, but by shutting down the Brewers, he shrank it considerably. On Wednesday night, he’ll have his next chance to chip away. Statistically speaking, Kershaw can shrink the distance between his regular-season and postseason selves only so much in the starts he makes this month. But if those starts send the Dodgers past the Padres and on to a long-awaited World Series win, the remaining gap will be forgotten.

Thanks to Dan Hirsch of Baseball-Reference and Jessie Barbour for research assistance.