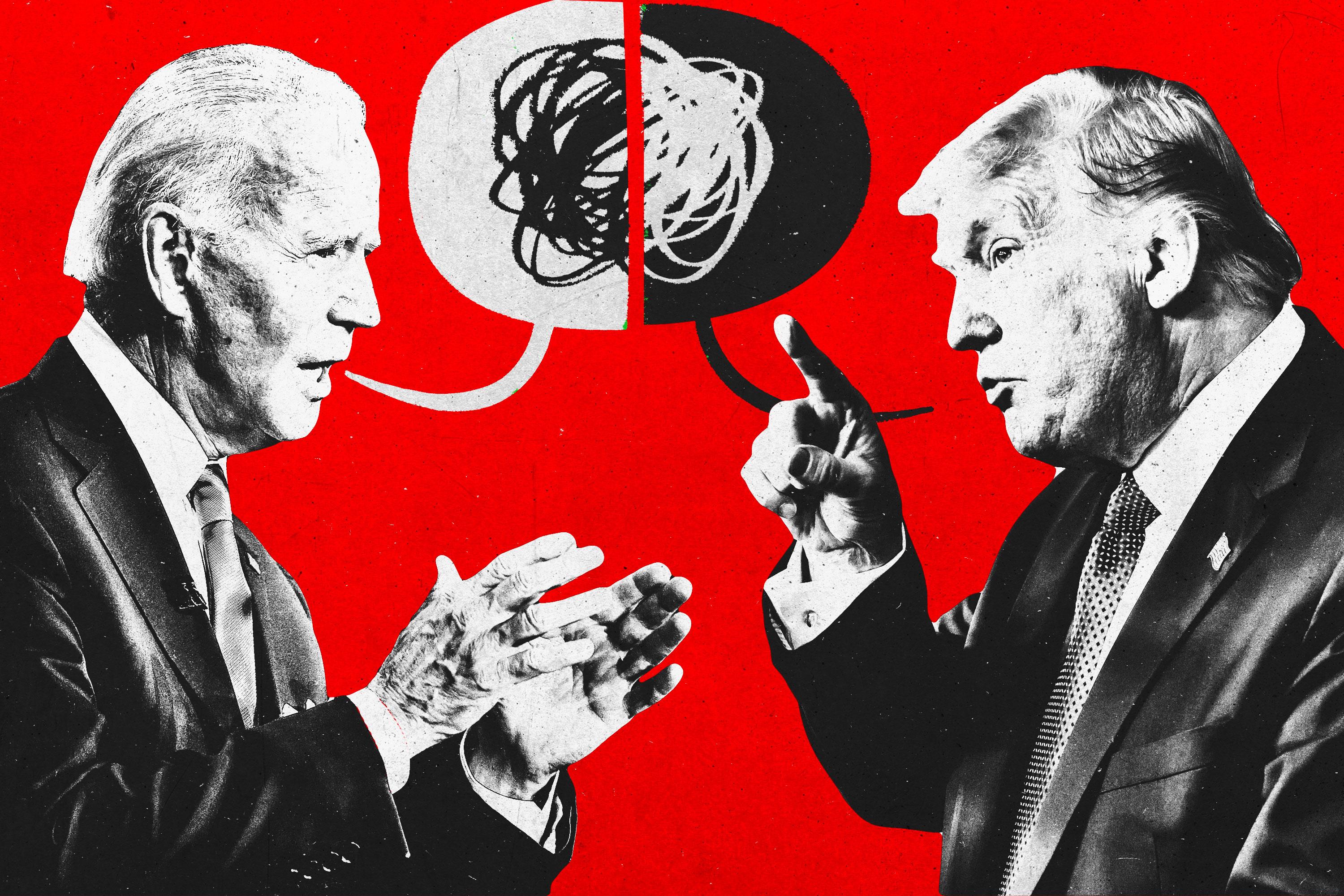

At the very least, Democrats and Republicans can agree to one (and only one) common proposition about the current state of national affairs: The United States is spiraling into a rare, strange political crisis. But what is the cause? There’s the coronavirus pandemic, which has killed more than 900,000 people worldwide, including more than 190,000 people in the U.S.; ongoing skirmishes between left-wing activists, right-wing counterprotesters, and police departments across the country; and renewed unrest after recent police shootings in Kenosha, Wisconsin, and Rochester, New York, the latter of which led to the resignation of the police chief after accusations of a cover-up. Now there are wildfires wreaking havoc across California, Oregon, and Washington, which have blanketed much of the West Coast in ash and an orange, cataclysmic haze. There are so many crises, plural, that pundits are having their own meta-crisis in determining which is the definitive one in the presidential election: Donald Trump is choosing the protests; Joe Biden has picked the pandemic.

Until the latest wildfires started raging through the Pacific Northwest a few days ago, the protests yielded the most explosive scenes in the country: progressive activists hurling firebombs in Washington, right-wing groups brandishing assault rifles in Michigan, police forces tear-gassing and wrangling protesters in nighttime escalations. On August 23, a police officer in Kenosha shot Jacob Blake, an unarmed Black man at the scene of a domestic disturbance. Blake is now paralyzed from the waist down. The subsequent protests in Kenosha spell a darker chapter in the otherwise optimistic demonstrations since George Floyd’s death in Minneapolis almost four months ago. Two days into the Black Lives Matter demonstrations in Kenosha, Kyle Rittenhouse, a 17-year-old vigilante from Illinois, shot and killed two protesters and injured a third while patrolling the city with his AR-15. Wisconsin prosecutors charged Rittenhouse with first-degree intentional homicide. Rittenhouse’s lawyers said he acted in self-defense and fired his weapon after protestors swarmed him. Quickly, Trump parroted Rittenhouse’s self-defense claim: “He probably would’ve been killed,” Trump said, “but it’s under investigation.”

Conservatives expect Kenosha to bring a popular backlash against the nationwide protests, thus bolstering Trump’s reelection chances. Clearly, Trump and his critics perceive two very different crises in policing: Democrats worry about police misconduct, while Republicans worry about anti-police sentiment. In fact, Democrats and Republicans perceive two very different crises in general: Republicans rank the coronavirus far below the economy among their priorities in this election in recent surveys.

Joe Biden and Trump made separate visits to Kenosha last week. Biden met with Blake’s family; Trump met with shopkeepers and police officers. As the protests swelled in Kenosha, speakers at the Republican National Convention in Charlotte discounted one crisis in order to underscore another. “In the midst of this global pandemic, just as our nation had begun to recover, we’ve seen violence and chaos in the streets of our major cities,” Vice President Mike Pence said in his nomination speech. “In the strongest possible terms,” Trump said in his prime-time remarks, “the Republican party condemns the rioting, looting, arson and violence we have seen in Democrat-run cities, all—like Kenosha, Minneapolis, Portland, Chicago and New York, many others—Democrat-run.” By painting his opponents as tolerant of mob rule in American cities, Trump once again announces his intention to run as a strongman, his reelection campaign premised (however hypocritically and even paradoxically) on restoring the “law and order” that has disintegrated all throughout his first presidential term.

But the latest polls reflect steady support for the protests. “Polls conducted this week and late last week suggest that public attitudes aren’t really breaking in Trump’s direction,” the elections analyst Geoffrey Skelley writes for FiveThirtyEight, “even though the Republican National Convention focused a great deal on characterizing the Democrats as the party of chaos and anarchy.” Besides, Trump isn’t exactly a role model for well-adjusted governance or a well-ordered society. For liberals, Trump is a constitutional and humanitarian crisis personified. His mismanagement of the virus has exacerbated the worst pandemic in a century. But even before the pandemic, Trump terrified his critics. He’s the rare president whose election represented a crisis for civil rights and democratic governance (Bush vs. Gore notwithstanding).

A few days ago, Columbia Journalism Review published a story about Trump’s unrelenting ubiquity in cable news segments. “In 2017, as Trump began his presidency, he averaged 110 minutes of speaking time per day; in 2018 it was 114 minutes; in 2019, 112 minutes. So far in 2020, it has been 110 minutes,” the sociologist Musa al-Gharbi writes. “If people are exhausted, it’s no surprise: news media have basically been running with 2016 campaign-level attention on Trump for four years straight now.” Al-Gharbi blames the news media for “fetishizing the president,” echoing the president’s supporters and some left-wing contrarians who have diagnosed liberals with “Trump Derangement Syndrome” ever since his election. In fairness, though, Trump’s unrelenting scandalousness owes to his official capacities, and not just his persona and his tweets: His senior advisers have been indicted, his campaign manager was sent to prison, he’s been impeached, and all the while, he’s demonstrated some profound and spectacular cynicism in his public pronouncements about, well, everything. Contrary to his current law-and-order posturing, Trump once reveled in his self-serving cynicism about deadly political unrest in the U.S. The crisis in Minneapolis and Kenosha began, in some crucial sense, in Charlottesville in 2017, when Trump plainly stated his disinterest in political de-escalation and righteous distinctions between protest factions: “I’m not putting anybody on a moral plane,” Trump said about the “Unite the Right” rally three days after a white supremacist rammed his car into a crowd of counterprotesters, killing Heather Heyer.

If Trump can’t perceive the public health crisis for the rest of the country, he can at least perceive the pandemic as a crisis for his reelection efforts. On Wednesday, Bob Woodward, promoting his new book, revealed a series of interviews he had with Trump in February and March about the coronavirus. “I wanted to always play it down,” Trump told Woodward in March, even as he discounted the potential spread and death toll in his earliest press briefings about the coronavirus, “I still like playing it down because I don’t want to create a panic.” Trump now denies Woodward’s account, but Woodward taped the conversations, which have launched all sorts of commentary about Woodward’s decision to withhold his reporting while Trump obscured the public health crisis. What if Woodward had embarrassed Trump and illuminated the public health threat sooner? Aren’t we silly for thinking any of this would have changed Trump’s course? And there you have the crisis of apathy that may well render all other crises moot.