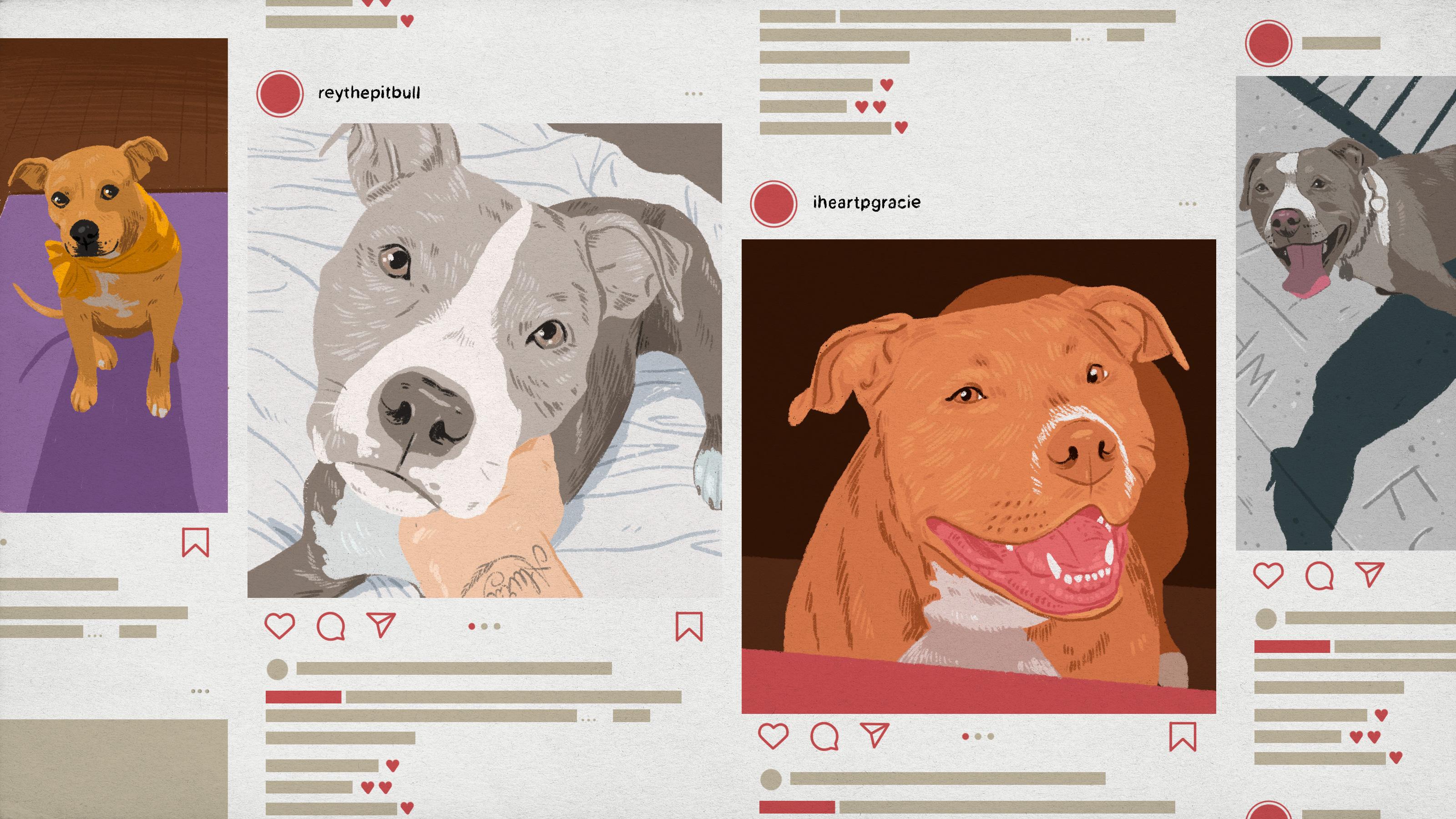

The Pit Bull Influencers Reclaiming the Dogs’ Image, One IG Post at a Time

Arguably no dogs have been as feared and maligned as the ones classified as pit bulls. But don’t tell that to Instagram stars like Gracie, Rey, and Bronson, just a few of the good boys and girls who are showing just how sweet the breeds can be.The Ringer hereby declares this Wednesday, August 19, 2020, to be Dog Day. We have no concrete reason for doing so, other than the fact that dogs are great and ought to be celebrated. We hope you agree.

Before Gracie had 100,000-plus Instagram followers, a burgeoning international fan base, and a deal with the premier talent management agency for animal influencers, she was left tied to a fence in Brooklyn, her russet-colored forehead specked with scattered puncture wounds from dog bites. She sat, silently bleeding, for nine hours, until the owner of the home where she was tied up found her in the daylight. The dog bite on Gracie’s jaw was so infected that it looked like it had been slashed by a knife. At the hospital, Gracie needed surgery for necrotic gum and jowls tissue from her infected bite wounds. The tip of her tail, which had been split open, was amputated.

Tanya Turgeon was still mourning the death of Elsie, her tawny pit mix, when she first saw Gracie in a video shared by a local rescue organization. In the clip, Gracie sat patiently, tail at a high-speed wag, to take treats from the volunteers in the emergency animal hospital. Turgeon saw a glimpse of the resilience and goofiness that had solidified her bond with Elsie, and reached out to bring Gracie home.

“I don’t know what most people would think when they see that video, but to me I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, that dog is in so much pain but she’s still so friendly. That’s the dog for me,’” Turgeon says.

Four years later, Gracie has met fans from 37 states and 20 countries, is certified as an advanced trick dog, and has volunteered as a clown dog at a bereavement camp. Her devoted social media fans leave her compliments about her ears (floppy), her eager waddle (muppet-like), her jowls (“a-jiggling” as she runs through the grass after a morning poop), and her general demeanor (she is a very good girl). Gracie’s comment section is flooded with hearts and paw prints and cry-laugh emoji at clips of her dunking her heart-shaped nose in an entire carton of whipped cream or practicing leg weaves.

Dog influencers are the natural next step in social-media marketing. They don’t need filters, aren’t picky about their best angles, and can’t slip up with a career-canceling gaffe. There are celebrity dachshunds with 800,000-plus Instagram followers and New York Times bestselling books, and Shih Tzus posing in a Fiat and behind platters of Raising Cane’s.

But pups like Gracie, a 70-pound American Staffordshire mix, have a public relations mission to address before they take on outside clients. “Pitfluencer” owners are fueled by the same indulgent conviction that afflicts most dog owners: the belief that everything their pup does is adorable and post-worthy. But pit bull–type dog owners are also chronicling their dogs’ legs-up snoozes, kiddie pool dips, mid-park poses, and morning greetings in hopes of breaking down long-standing stigmas and misconceptions.

“You have all of these different accounts, with their names, and you get to see what they like, and what they don’t like, and at the end of the day, they’re just a family dog living in that environment, doing family dog things,” Turgeon says.

“I can share what [Gracie] actually is, and no one can take that away from her. It really allows people to fall in love with the animal, and there really is no label involved.”

Pit bull–type dogs—for years, reviled, feared, fought, and abandoned—are now the internet’s most lovable underdogs, thanks to Instagram influencers showing the softer, innocuous side of one of America’s most misunderstood pets.

The first common misconception about pit bulls is the simplest: Most dogs classified as a “pit bull” aren’t actually pit bull terriers. It’s a broad term, in the way that beagles and Rhodesian ridgebacks are both technically “hounds” despite weighing roughly 20 and 90 pounds, respectively. “Pit bull” is a classification used to describe four distinct breeds: American pit bull terrier, American Staffordshire terrier, American bully, and Staffordshire terrier. It’s an umbrella term that places Bronson, a short and stout 62-pound bully with a champagne tri-color coat and 220,000 Instagram followers, in the same category as Rey, a “pocket pittie” just a hair over 40 pounds with a slate-colored coat, a white underbelly, and 38,500 followers.

The second misconception is about demeanor: Pit bull–type dogs are often assumed to be more aggressive and dangerous. It’s reductive to assume every dog of one breed has the same personality, but humans struggle to avoid generalization among their own species, let alone another one. Breed-specific legislation targeting these types of dogs spans from inconvenient (extra pet deposits for renters with pit bull–type breeds) to exclusionary (American pit bull terriers are banned from importation to Australia).

It will be someone who I don’t recognize their name who will message and be like, ‘Yeah, we adopted our dog three years ago because of Gracie.’ … I think the dogs I’ve helped are dogs I’ve never heard of.Tanya Turgeon

In “The State of the American Dog,” Tom Junod delves into the ubiquity (and controversy) of pit bull–type dogs. They are a distinctly American dog, he writes, in the way in which we characterize ourselves as “a country of rescues, a country of mutts”; they are also distinctly American in the way in which they reveal the dissonance between the nation’s intentions and its realities:

There is no other dog that figures as often in the national narrative—no other dog as vilified on the evening news, no other dog as defended on television programs, no other dog as mythologized by both its enemies and its advocates, no other dog as discriminated against, no other dog as wantonly bred, no other dog as frequently abused, no other dog as promiscuously abandoned, no other dog as likely to end up in an animal shelter, no other dog as likely to be rescued, no other dog as likely to be killed.

It wasn’t always this way. In the first half of the 20th century, the pit bull was a quintessential American dog. Sgt. Stubby, a pit mix, was part of four major offenses during World War I, led American Legion parades, and earned a New York Times obituary. American pit bull terriers were used in wartime advertisements. Both Teddy Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson reportedly had pit mixes. Some claim pit bull terriers were even used as “nanny dogs” in the early 1900s.

But the breed took a serious image hit in the ’80s. They became the defense dog of choice for drug dealers around the country. “The dogs are legal to own, more terrorizing than guns and better at delaying police,” reads one wire story from 1987. The same year, Sports Illustrated published a cover story that declared pits a “friend and killer.” Dog fighting, which was outlawed in all 50 states by 1976, picked up in popularity in the ’90s, and the prevalent breed in American fighting rings is the pit bull terrier. In 2007, nearly 50 dogs, mostly American pit bull terriers, were seized from then–Atlanta Falcons quarterback Michael Vick’s property.

The number of pit bull and pit mixes euthanized in the United States per day is between 2,000 and 3,000. Some studies estimate only one in 600 pit mixes will be adopted, and that about 75 percent of municipal shelters euthanize a pit mix immediately upon intake. Numerous animal behaviorists and scientists have dispelled assumptions about pit tendencies toward aggression. Studies instead show that the majority of dog bites come from animals that haven’t experienced positive human interactions (76 percent) or that are chained or isolated (73 percent). Any dog that’s chained is statistically more likely to bite, but someone looking for a guard animal is more likely to choose a hefty pit mix with a baritone bark over a 7-pound Yorkshire terrier.

When I reached out to Turgeon, I let her know I was coming in with a bit of bias: My four-year-old dog, Scout, is a rescue that was classified as a pit-hound mix, though from certain angles, he looks more like a Chihuahua or Baby Yoda. We chatted about some of the more unexpected factors of pit ownership, like the unsolicited comments from friends, family, and strangers about pit behaviors. If I show someone a picture of Scout curled into my lap, they ask about his breed or try to guess his mix. But if he’s out on the porch, shoulders stiffened with Staffy-like muscularity, yelping at someone who is wearing a hat in a way that offends his sensibilities, passersby will ask whether he’s part pit bull. His good traits bring about speculation on his lineage. His more abrasive tendencies bring up questions about which pit bull–type breed is in his DNA.

Turgeon had a comparable learning curve. She felt neutral about pit bull types before she got Elsie, and she assumed others felt similarly.

“I didn’t really think anything of it,” Turgeon said. “I thought no one else thought anything of it. I was super naive, but everybody was yelling their opinion all day long. That’s when I realized having this kind of dog came with other stuff.”

Putting Bronson content out there has helped a lot of people realize that some of the misconceptions about these dogs are crazy and not true.Sydnee Gilletti

One guy on the street told Turgeon both her and the dog looked mean. Two different men told Turgeon she had no business “having that kind of dog.” Parents would let their children crouch down to pet Elsie, then quickly put the kid away after asking Turgeon about her breed.

Turgeon began to use social media to showcase Elsie’s goofier side. She started Movie Mondays, which featured the duo imitating classic film shots like the kiss from The Notebook (Elsie played Allie) or the cover of American Beauty. It was an attempt to sweeten two things that the public tended to dislike: Mondays and pit bulls. When Elsie got breast cancer, Turgeon raised money for the Humane Society of New York by selling pink paintings Elsie made using her paws and tail. When Turgeon adopted Gracie, she continued the tradition of showcasing her dog’s daily happenings. Gracie’s page has clips that display her mastery of tricks and commands, but also simple, candid moments that showcase her connection to humans and her everyday dog pursuits.

Those prosaic moments, without fanfare or posing, are often the ones that do best with followers, says Jacqueline Keidel Martinez, Rey’s owner. Unlike Turgeon, Martinez had previous experiences with pits before she adopted Rey and her other dog, KJ. Her father gravitated toward more “vilified breeds,” she says, and she grew up with Dobermans and Rottweilers. When she was 16, a few years before the Vick dog-fighting scandal, her father brought home a pit bull terrier, who was a “wonderful family dog.” Martinez adopted KJ and Rey knowing they were likely to be emotive and goofy, like many pit mixes, but she was also prepared to face the interrogations that these dogs sometimes prompt. Martinez works in public relations, and she began Rey’s Instagram account as a testing ground to learn more about the app’s algorithm. Now it’s a chance for her to show a soft, everyday dog side to a pit, and counter the violent, fight-centric imagery that accompanied portrayals when Martinez was a teen.

“Sixteen years ago, when social media wasn’t what it is today, all we had were sensationalized reports about pit bulls mauling children and dog fighting,” Martinez says. “This kind of puts the power back in our hands to change that narrative.”

The world of pitfluencers covers multiple breeds, countries, personalities, and presentations. Staffies Darren and Phillip from Australia (723,000 followers) model their custom robes and wool-knit sweaters. Pirate, an American Staffy mix in Los Angeles (66,100 followers) has a penchant for headwear. Noah and Lincoln are stout, serious-looking rescued American bullies (177,000 followers) built like hippos. These pitfluencers answer Q&As about foster processes, explain raw food diets, and show off dog toy deliveries. Along the way, many educate the scrolling public about adoption and rescue processes.

Turgeon regularly hears from internet strangers who say how Gracie inspired them to seek out a rescue dog, or changed their perception of pit bull–type dogs.

“It’s the quietest followers who you don’t realize that you’re touching,” she says. “It will be someone who I don’t recognize their name who will message and be like, ‘Yeah, we adopted our dog three years ago because of Gracie.’ … I think the dogs I’ve helped are dogs I’ve never heard of. Just ’cause someone saw the account and was like, ‘Oh my god, you made me fall in love with this I’m going to go adopt,’ and it’s a dog I didn’t even know about. So even if that happens once, that makes me over the moon.”

Sydnee Gilletti and her husband adopted Bronson, a three-year-old American bully, when he was seven months old. His ears had been cropped by his previous owner, and his two ochre eyebrows give him a bit of a perpetual quizzical look. Bronson’s account features clips of him cuddling with Gilletti’s other bully, Kush; trying his first pickle; and bounding up the stairs with a chew toy in his jaws. The feed came in handy when Gilletti and her husband purchased their most recent home. The homeowner’s association had rules against pit bull–type breeds, and Gilletti prepared what she called a “dissertation” to defend Bronson’s and Kush’s character, and brought in the Instagram account as another piece of evidence.

“Putting Bronson content out there has helped a lot of people realize that some of the misconceptions about these dogs are crazy and not true,” Gilletti says.

Bella Boone adopted Baloo, a three-year-old American Staffordshire terrier and red heeler mix, in her first year of college. The day she met Baloo, she had been sitting next to him in the shelter when a couple walked by and remarked on how beautiful Baloo looked. They asked about his breed, and Boone pointed at his information sheet, which listed “American pit bull terrier.” The couple gasped and the woman said, “Oh never mind.”

“Just saying the word ‘pit bull’ is enough to turn people away, even if their initial impression was positive,” Boone says.

Not a day goes by without a negative interaction because of Baloo’s looks, Boone says. Other dog owners leash up their pups and flee the dog park when they arrive, or ask whether Bella should be bringing “that kind of dog” into the space. The “hate increased tenfold when people are able to hide behind a screen,” Boone says. But Baloo has also garnered a loyal following of 150,000-plus followers on Instagram and more than half a million followers on TikTok.

“I try to show my followers that a bully breed can be just as well trained as a German shepherd, as friendly as a golden retriever, and as cute as a doodle,” Boone says.

“We get a lot of messages from people saying that they didn’t know pit bulls could be so smart, that they have never seen a pit bull be so sweet around other animals, or that they can’t believe that a pit bull could be so calm. Though the majority of our followers are pit bull lovers, we have gotten numerous messages from people saying they had been previously scared of pit bulls but have since changed their minds because of Baloo.”

Gracie, Baloo, and Bronson are all signed with the Dog Agency, the animal influencer management company started by Loni Edwards in 2015. The Dog Agency represents roughly 160 clients spanning the animal kingdom, from Chihuahuas and malteses to pigs, hedgehogs, and tortoises. Seventy percent of Edwards’s clients are dogs, and roughly 10 percent are pit bull–type dogs; they’re the second-most-common pup among her canines, besides golden retrievers (11 percent).

Baloo has had branded partnerships with Sony Music and Swiffer. Bronson posted a video with an emphatic whine-wag combination that was roughly translated (by Gilletti) into an ad for Netflix’s Space Force. Rey recently posted her first major ad campaign with Swiffer. Lily Bug, another of Edwards’s clients, promoted Capitol Records with a clip of her intently watching a Katy Perry video.

“Dogs are extremely effective marketers,” Edwards says. “They have everything that human influencers have, plus all of these factors that are so incredibly powerful and emotional, and when you’re marketing and you have that emotional element, there’s nothing that beats that.”

Pit bull types garner an exceptional amount of interaction because of their maligned identity, Edwards says. Consumers love an underdog.

“Bullies in particular tend to have an incredible engaged fan base, I think because of the stigma. I think because they’re the underdog … people are even more committed and even more engaged and love them that much more,” Edwards says. “There’s just that extra layer with people going above and beyond to break stigmas, to show how lovable they are.”

Most of the human handlers behind pitfluencers didn’t start their social media pages in hopes of brand partnerships or extra cash. That’s just an added bonus. They shared photos because they loved their flat-nosed, perky-eared pit mixes, and hoped others would find joy in glimpses of their pup’s everyday life. Back when Turgeon started Elsie’s accounts, she made it a point to share her without a focus on breed. She wanted to showcase her personality without followers coming in with expectations about her demeanor because of her DNA.

“My whole thing was I’m just going to share her without a label, because my whole thought was to let the people just fall in love with her as much as I love her too … and if people love her too, that’s awesome,” she says. “They’re forming their opinion based on her, and not anything else.”