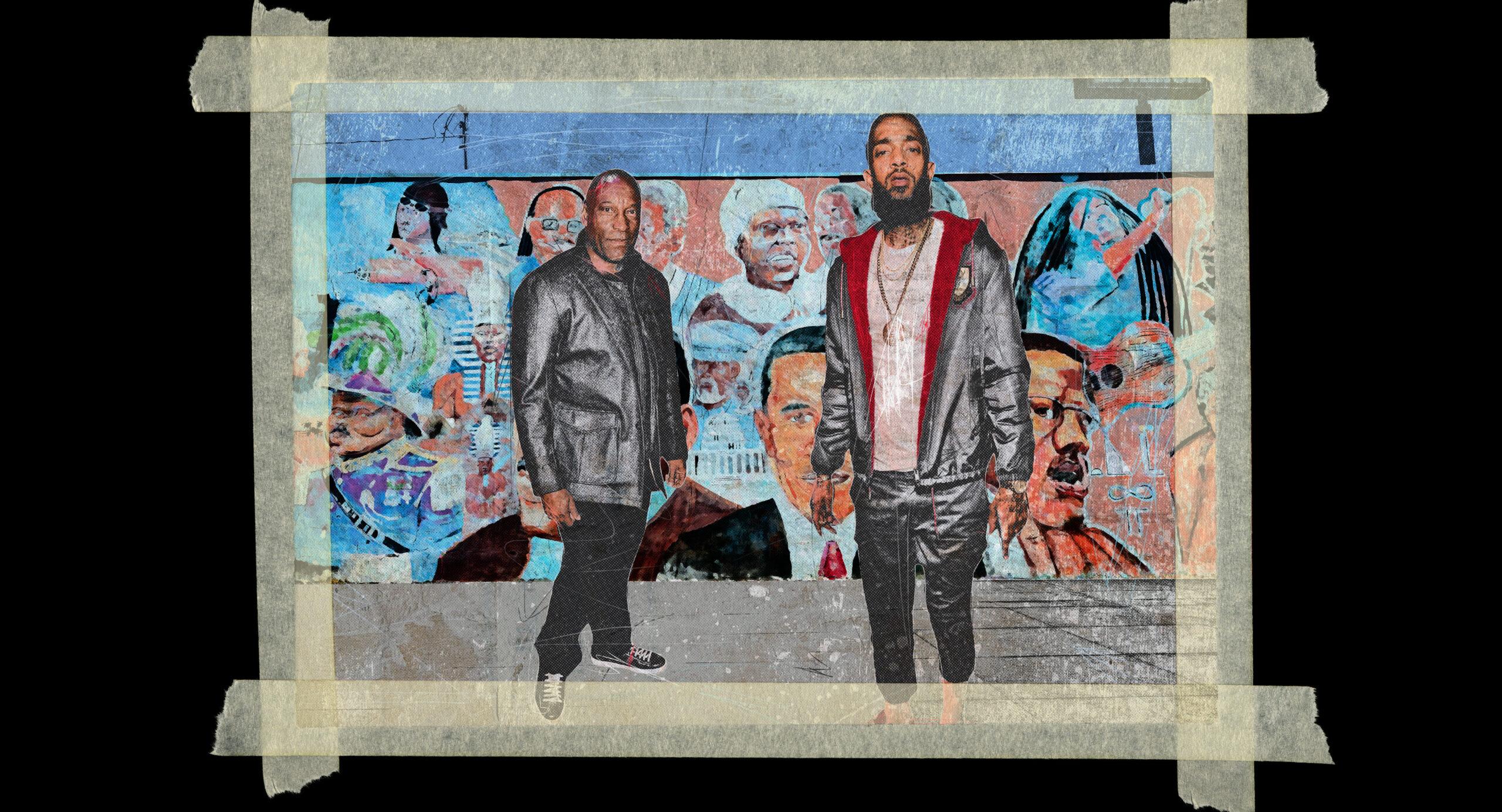

The Lasting Bond Between Nipsey Hussle and John Singleton, From South L.A. to Beyond

The rapper and director both called the same neighborhood home and had a mutual respect for one another’s work. But their connection runs deeper than that. On the eve of what would’ve been Nipsey’s 35th birthday, we explore who and what they represented—and why.On March 31, 2019, Ermias Asghedom, the rapper and entrepreneur best known as Nipsey Hussle, was shot and killed in the parking lot outside his Marathon Clothing store in South Los Angeles. He was 33. Less than two weeks later, director, writer, and producer John Singleton shared a tweet from XXL Magazine showing a video of Hussle’s mother, Angelique Smith, urging his supporters not to mourn his death, because “his energy is everywhere.” “Wise words,” Singleton wrote. “Take heed!” Singleton suffered a stroke one week later and was taken off life support on April 28. He was 51.

The untimely deaths of two iconic figures with global influence within one month of each other amounted to a monumental loss. But the devastating one-two punch of their deaths isn’t the tie that binds Hussle and Singleton together. It isn’t that services for both were held at Angelus Funeral Home on Crenshaw Boulevard in South L.A., or that both were laid to rest at Forest Lawn–Hollywood Hills cemetery. It’s not that Hussle’s partner, actress Lauren London, was originally cast (“handpicked by John Singleton,” a proud Hussle informed GQ in a 2019 profile of the couple that ran shortly before his death) and filmed the pilot episode for Snowfall, the FX series chronicling crack’s origins in South L.A. that Singleton helped create. It isn’t that Singleton directed a 2017 episode of Billions titled “Victory Lap,” the same title as Hussle’s acclaimed, long-awaited 2018 debut studio album. And it’s not that Hussle and Singleton both hail from South L.A. These connections are mostly surface-level—ironic, in some instances—and purely observational. Their true connection is in who and what they represented, as well as why.

Despite belonging to different generations, Hussle and Singleton had similar influences. Singleton visualized the gritty details that many early titans of L.A. hip-hop described in their music via his 1991 debut, Boyz n the Hood. Hussle descended from that lineage, advancing it while still adhering to the same principles and aesthetic. Although their upbringings were different, both grasped the unlikelihood of their accomplishments and understood what they symbolized to other Black people looking to thrive in a world with no interest in their upward mobility. “If there’s not more John Singletons, there’s gonna be a lot more carjackings,” Singleton, who had two Oscar nominations by 24, jokingly told Entertainment Weekly in 1993—but with a clear sense of self-awareness. Hussle, meanwhile, believed the greatest thing any individual can do is inspire others—and that it was his responsibility to fill that role for as many Black people as possible.

Both made where they came from, and the legacy accompanying that, central to what they did. John Singleton and Nipsey Hussle, who would’ve been turning 35 on Saturday, are bound by their dedication to the preservation of Black culture and the advancement of Black people. Though their lives ended far too soon, this was their life’s work. And that work will stand tall forever.

“Niggas ain’t seen L.A. like this since Boyz n the Hood,” Hussle told The Fader in 2009. Singleton was a hip-hop fan who grew up observing what Ice-T, N.W.A, and Compton’s Most Wanted, just to name a few, documented on record. It isn’t just that he translated this onto the big screen, it’s that he took what terrified white America about places like South L.A.—its inhabitants—and humanized them in groundbreaking fashion. Hussle—who grew up in that environment in the wake of Boyz n the Hood and West Coast hip-hop’s explosion through rappers like Ice Cube, Dr. Dre, Snoop Dogg, and 2Pac, and who called himself the 2Pac of his generation—embodied many things Singleton captured in Boyz n the Hood. Part of that was his thick L.A. accent, which sharpened into a raspy growl when rapped.

“I’m originally from Detroit, but I’ve been in L.A. since the early ’90s,” says Todd Boyd, a professor who studies the intersection of race and popular culture at the University of Southern California. “But when I got here, the thing that struck me was the way that Black people in L.A. talk. So as I’m listening to ‘Victory Lap’—‘I’m an urban legend / South Central in a certain section’—I’m hearing that around me every day. Nipsey sounded like L.A. to me. I could be anywhere in the world and hear that, and it would connect me with L.A.”

Hussle’s connection to L.A. was in everything he did. His legacy is forever bound to Slauson Avenue and Crenshaw Boulevard, as the intersection (where the Marathon Clothing store was located) is where he sold mixtapes out of the trunk of his car and, tragically, where he was killed. Now it’s hallowed ground, officially renamed “Nipsey Hussle Square” following his killing.

South L.A.’s Crenshaw district—the neighborhood that made him who he is—became the inspiration for his 2013 mixtape, Crenshaw, which he promoted using a piece of iconography that Singleton made famous almost 25 years prior. In Boyz n the Hood’s final scene, Tre (Cuba Gooding Jr.) wears a black T-shirt with “CRENSHAW” emblazoned across its front. Even though he’s pulling away from his neighborhood, it’s a key part of who he is. The shirt became immensely popular in light of the film’s canonization, which Hussle recognized and implemented as part of Crenshaw’s rollout. The project’s cover features an image of Hussle, arms folded, wearing his own version of the shirt and a matching hat. It’s sold on the Marathon Clothing Store’s website, and following Hussle’s and Singleton’s deaths, footage spread showing Singleton visiting the store’s brick-and-mortar location and recounting to Hussle’s father the story of how the original made it into the film. The idea of Crenshaw as a cultural identity was the foundation for the mixtape. It begins with “Crenshaw Blvd,” a clip of the infamous scene where the self-loathing Black cop terrorizes Tre after pulling him and Ricky (Morris Chestnut) over. The intro closes with the cop asking Tre whether he’s a Crenshaw Mafia Blood or a Rolling 60’s Crip, the same renowned set Hussle was a member of.

Through them both being natives, they were able to draw inspiration and encouragement with a sense of unity beneath it.DJ Chubb E. Swagg

“Nipsey was able to galvanize people around that same shirt, the same concept, and those same feelings,” says DJ Chubb E. Swagg, a South L.A. native who DJed for Hussle during the early aughts. “Through them both being natives, they were able to draw inspiration and encouragement with a sense of unity beneath it. The whole project draws upon the inspiration of not only where you’re from, but taking it back.” This type of imagery and spirit resonated so deeply because both invested so much in the power of their bona fides.

There was a level of certification that was essential to everything Hussle and Singleton put their names on. “Go through every album, every song and then point out one lie,” Hussle told Complex in 2013. Respect, integrity, and reputation were paramount to Hussle; so was never straying from his roots, even as his profile grew. “Success, I just want my fair share in life / In that self made, I ain’t tryna hear life / Still proud of what I look at in the mirror life / Hyde Park Hussle half-baked on a Paris flight,” he rapped on Crenshaw’s “No Regrets.” He couldn’t be “Neighborhood Nip” if he couldn’t show his face in the neighborhood, so how could he ever abandon it? In Hussle’s eyes, maintaining an active presence in his community was the best way to improve it. “If you look at his work and had to assign a percentage, like 95 percent of that is him speaking to Crenshaw up to Slauson,” says Gerrick Kennedy, an author and journalist, formerly of the Los Angeles Times, who profiled Hussle and London for GQ. “That makes people attach themselves to it. I think so much of that is about being able to see yourself reflected back in the art.”

Singleton, meanwhile, safeguarded his vision as best he could in Hollywood. Everything he did, particularly with stories such as Boyz n the Hood, 1993’s Poetic Justice, 2001’s Baby Boy, and Snowfall, which focused on Black people in L.A., had to meet his standard of authenticity. “I try to make everything as authentic as possible, so I feel like everything I make will propagate in different ways,” he told me in 2017, just before Snowfall’s premiere. “If it’s real, people will find meaning in it—meaning I’m not even aware of right now.” Author and journalist Veronica Chambers, a longtime friend of Singleton who cowrote 1993’s Poetic Justice: Filmmaking South Central Style with him, says he always trusted his voice. “I think John felt if there’s a movie he wanted to see or a show he wanted to make, he had to try and do it,” she says. “Every time I look at Regina King, I can just remember sitting next to John at the camera, and he’s filming her in a van with Janet Jackson, 2Pac, and Joe Torry, and I’m like, ‘He did that.’ He had a vision of girls with box braids hanging with guys, driving up the coast, and it was a little unlike anything we’d seen before.”

Additionally, Singleton’s commitment to authenticity came across in his casting decisions. He put an AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted-era Ice Cube in his very first film, then later cast him in Higher Learning. He made Tupac the second lead in Poetic Justice. And not only did he cast Snoop Dogg (who was very popular by the early 2000s, but not ”cohost a celebrity guest-appearance vehicle with Martha Stewart” popular) in Baby Boy, he also cast the remaining two-thirds of Snoop’s group Tha Eastsidaz: Big Tray Deee and Goldie Loc. These choices ensured a degree of accountability, as did the greater challenge of properly representing the mosaic of Black people in South L.A., because he’d damn sure hear about it if he failed at that. But this was a task Singleton didn’t run from.

I think John felt if there’s a movie he wanted to see or a show he wanted to make, he had to try and do it.Veronica Chambers

Both Singleton and Hussle were notably outspoken at times. “If I learned anything on this movie,” he told The Guardian in 2000 of his Shaft remake’s difficult production, “it’s that I’ve got passion, and for people who don’t, I make them see how trite their lives are.” But so much of what came across as arrogance was Singleton trying to protect his vision. He didn’t want a white director bringing Boyz n the Hood to life. 1997’s Rosewood is his most ambitious film, but he attributed its commercial failure to Warner Bros.’ fear of its searing depiction of white resentment. “They were afraid of the picture,” he told The New York Times in 2005. “You’re talking about black genocide.” “They ain’t letting the black people tell the stories,” he said of major studios during a 2014 interview with The Hollywood Reporter’s Stephen Galloway, later adding that Hollywood’s “so-called liberals” believe they aren’t racist because they grew up with hip-hop.

A great deal of Singleton’s frustration likely came from having to make creative concessions due to the nature of the film industry, something Hussle was able to avoid as an independent artist. He maintained control of his music as a result, all while maintaining a “Fuck the industry” position. “I realized that the structure of these companies aren’t built to give me any type of ownership,” he told Complex in 2013, later adding, “it’s not because the people at the label didn’t want to help me. It’s because the corporate structure of their companies would not allow ownership. And I’m offended by that.” Even after Hussle negotiated a partnership with Atlantic Records that allowed him to operate on his terms, he continued to separate himself. “I ain’t nothin’ like you fuckin’ rap niggas” was a brazen statement of purpose. He was already a street legend several times over. Music simply amplified his gospel and provided more resources for efforts like STEM centers, small-business incubators, and coworking spaces in Crenshaw with plans for nationwide expansion. Hussle, like Singleton, didn’t just want more for Black people, he wanted the most.

So many of Singleton and Hussle’s actions made their love for Black people abundantly clear. Singleton found immense value in the impact his work had on others. “People come up to me and tell me what something I did meant to them, and I’m like, ‘I hadn’t even thought of that,’” he told me in 2017. “That comes from being an artist and having a certain level of authenticity in what you do. You inspire other people, you spark thought and perspective in them.” A 2019 Rolling Stone retrospective recalls him telling young, Black filmmakers, “Don’t be afraid to be Black.” “He didn’t believe you had to prove to white people how good you are or how smart you are,” Chambers says. “He was like, ‘We’re just out here being amazing all the time.’”

Hussle believed he had to lead by example because he’d succeeded against the odds. “I’d like to be one of those voices kids can look back and say, ‘Nip was giving me the game,’” he told me in 2018, following Victory Lap’s release. “‘Nip was telling me how to be self-sufficient. A real leader.’ And I’ll be proud of that.” His brash, pull-yourself-up-by-your-shoelaces capitalism didn’t inspire everyone, but it should be examined with the understanding that it was delivered with the express purpose of reaching people with similar backgrounds and aspirations. “There are nuances in my music that speak to people who come from street culture—and even more specific, people who come from gang culture,” he told me. “But overall, the macro message is that as you mine yourself for your unique contribution that you’re going to make, this is a journey. I went through all of the emotions, everything. And now I have a platform to talk about it, so I think my most powerful contribution is to just leave breadcrumbs.”

They were flawed people, but their imperfections didn’t overshadow what they did for Black culture—particularly in South L.A. Singleton’s career, from Boyz n the Hood to Snowfall, was bookended by telling these stories. Hussle told his own, along with those of many others, from Slauson Boy Vol. 1 to Victory Lap. He put everything back into the place that produced him. You can’t discuss L.A. in popular culture without including their contributions.

“I think you have to look at the body of work, tradition, and legacy. So when you look at that, it’s kind of like the Hall of Fame,” Boyd says. “If there was a Hall of Fame for Black culture like there is for the NBA or NFL and there was a ceremony, I would say that we would be inducting both John and Nip into that Hall of Fame.”

Julian Kimble has written for The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Undefeated, GQ, Billboard, Pitchfork, The Fader, SB Nation, and many more.