As of the morning of August 7, the Colorado Rockies—the fourth-best team in the NL West, by most preseason prediction models—are in first place. These are indeed strange times, and only getting stranger. The franchise that plays in the most hitter-friendly park in MLB has found this success by riding its starting rotation.

Through the first two weeks of the season, Colorado’s offense has been … just about fine. The Trevor Story–Nolan Arenado tandem has combined for eight home runs, but just 15 other hits. Charlie Blackmon (130 OPS+) has been good; Ryan McMahon (108 OPS+) has been a little better than expected; David Dahl (64 OPS+) will probably pick up the pace as the season goes on; and Daniel Murphy and Matt Kemp, two of the best hitters of the 2010s, are both trying to squeeze one more great season out of their aging bats.

As a team, the Rockies are hitting .266/.324/.420, placing them 20th in MLB with a wRC+ of 91. They’re somewhere near league average in strikeout rate and walk rate, and even though they’ve scored the sixth-most runs per game through Wednesday’s action, the Rockies have actually hit worse with men on base and runners in scoring position than they have in lower-leverage situations.

But through two weeks—read: 20 percent of this shortened season—Colorado’s pitching has been nothing short of exceptional. In totality, this group has the fourth-best ERA- in MLB and has held opponents to a .206 batting average and 3.27 runs per game. And while the bullpen (the injured Wade Davis notwithstanding) has been partially responsible for that, the Rockies’ rotation is leading the way with the second-best ERA- in baseball.

The Rockies have long had solid options at starting pitcher. In fact, the members of the team’s current fearsome rotation—German Márquez, Kyle Freeland, Antonio Senzatela, and Jon Gray—have all been on the roster since 2017. The issue was that at any point in the past three years, at least one of them was suffering a catastrophic meltdown.

No longer. It’s been only two and a half times through the rotation, but all four have pitched well enough so far to keep Colorado’s unremarkable offense ahead of the juggernaut Dodgers in the standings. So let’s take a look at Denver’s most successful Rock foursome since the Fray, and see how likely they are to keep this run going.

German Márquez

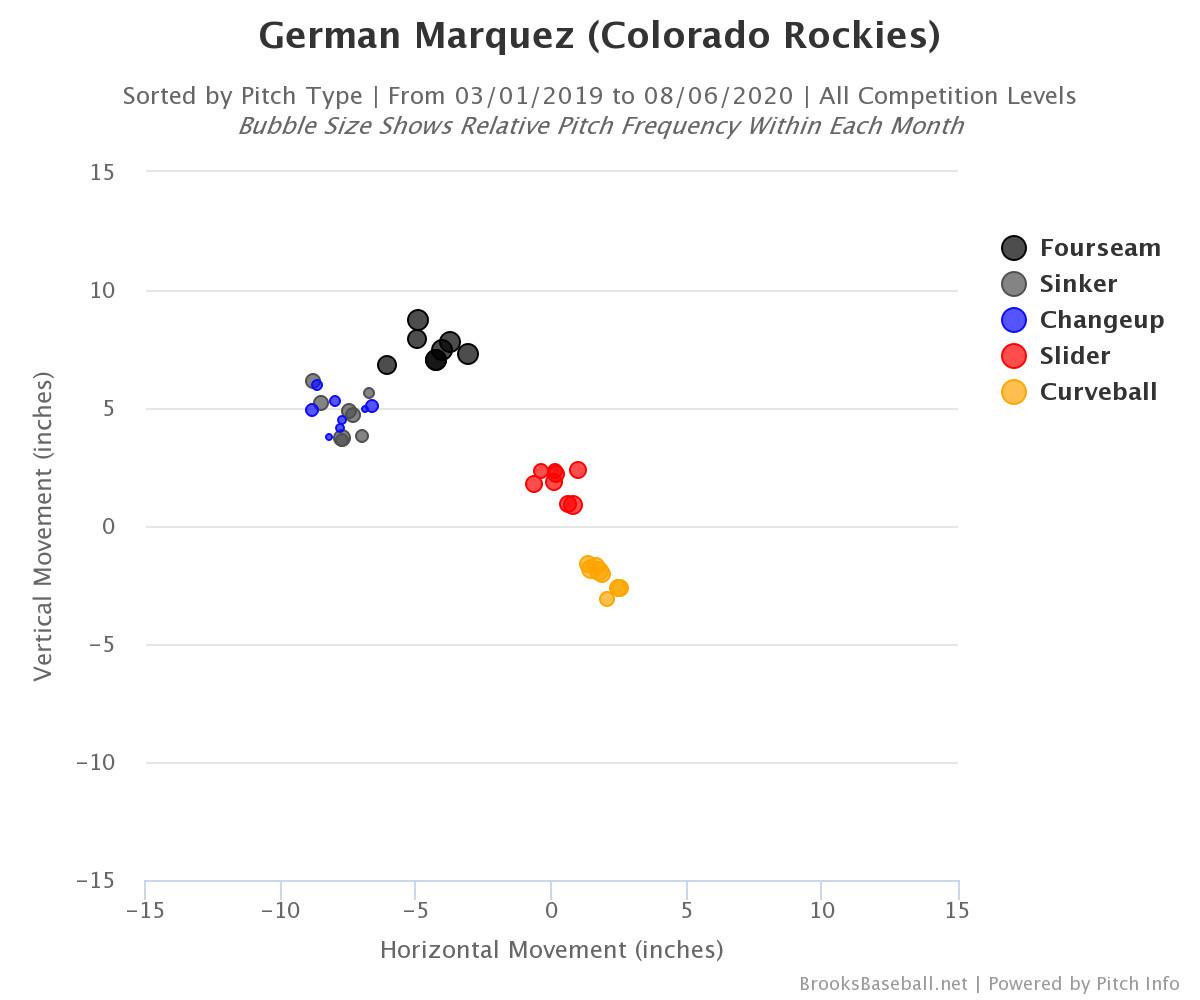

Out of all the Rockies’ starters, Márquez has the most obviously ace-worthy arsenal. He throws five pitches, including a four-seamer that averages 95.9 miles per hour. That velocity places him 19th among the 156 pitchers (many of them relievers) who’ve thrown at least 100 pitches this season. Márquez also has a 95 mph sinker, a changeup that he can run in on right-handed batters, and a pair of tight mid-80s breaking balls to spin away from them.

The first is a curveball that is more in the vein of the tighter Lance McCullers–style knuckle-curve than the Clayton Kershaw–style looping 12-to-6 offering.

It’s not even close to the fastest-spinning or biggest-breaking hook in the game, but you can almost hear the ball biting into the air as it changes direction on Marcus Semien in the GIF above. And unlike most pitchers with multiple breaking balls, Márquez has a slider that doesn’t look or move that differently from his curve.

The difference between the two is just a couple of inches of break and a couple of miles per hour, and neither pitch breaks very far laterally.

The key is that Márquez’s two fastballs are so hard and break so far to his arm side that the breaking pitches look like sweeping wipeout offerings in comparison. That fools hitters to the point that someone like Matt Chapman can just swing through an 88 mph slider right down the middle of the plate.

In 2018, Márquez’s breakout year, the right-hander made 33 starts and posted a 3.23 DRA with an ERA of 3.77, won a Silver Slugger by hitting .300 with a home run, and pitched well enough in September to win NL Pitcher of the Month. In 2019, Márquez posted a near-identical DRA (3.26) but saw his HR/FB rate pop up by 20 percent and his ERA spike to 4.76. A wild variance in outcomes is something of a theme for this Rockies rotation.

Kyle Freeland

In 2018, Freeland went 17-7 with a 2.85 ERA and finished fourth in an extremely tough NL Cy Young field. In terms of ERA and bWAR, it was the best season by a starting pitcher in Rockies’ history. But when 2019 rolled around, Freeland couldn’t get anyone out. His ERA ballooned to 6.73. He spent six weeks in the minors, then another month on the shelf with a groin strain. And unlike Márquez, whose underlying numbers were as steady as, well, a rock, Freeland’s sky-high ERA matched his DRA, which reached 6.30 in 22 big league starts.

So Freeland went away this offseason, junked his old repertoire and windup, and started over. He simplified his delivery to remove a hitch and improve his command, and through three starts this season, it seems like it’s working. He allowed just two runs over his first two starts, and pitched much better than his stat line would suggest in his no-decision against the Giants on Thursday.

Freeland’s most dramatic change is how drastically he’s cut his fastball usage. The 2014 first-rounder has always been more of a command-and-control lefty than a power pitcher, but this year he’s gone full Rich Hill. Here’s his percentage pitch usage by year heading into Thursday’s start against the Giants, according to Brooks Baseball.

Freeland Pitch Usage

After only two or three starts, results don’t tell the whole picture. Baseball is so inherently chaotic that even across 30 starts, luck and sequencing play a huge factor in the outcomes. But Freeland’s new, four-seamer-averse approach is worth taking note of immediately because one thing he has complete control over within a start is his pitch mix. And so far, with opponents hitting just .154/.233/.282, this new process is bringing about encouraging results.

Antonio Senzatela

Senzatela is a pitch-to-contact guy who plays his home games in Coors Field, which is kind of like being a slab of beef in a bear cage. Senzatela debuted for the Rockies at just 22 and has been at least a part-time starter for the past three-plus seasons. But he’s never exactly been Plan A.

The Rockies have traditionally had a tough time developing starting pitchers, which one might expect given the home-run-friendly reputation of Coors Field. In reality, pitching in Coors Field is an even nastier experience than the reputation would have you believe, because it’s not just a matter of home runs. Navigating that type of park isn’t that complicated a proposition: The early- to mid-1990s Braves, maybe the best starting rotation ever assembled, played their home games in a ballpark nicknamed “The Launching Pad.” But because the thin, dry air in Denver allows batted balls to carry farther than usual, the architects who designed Coors Field moved the outfield fences back, resulting in the biggest outfield in baseball. With so much ground for outfielders to cover, more bloopers drop in for singles, and more balls roll to the wall for triples.

And the thin air creates other complications, too. Athletes—including pitchers—tire more quickly and have a harder time recovering from exertion. Plus, the less dense the atmosphere, the less air resistance a pitched baseball encounters; so breaking balls—which move only because of differences in wind resistance across different portions of the baseball’s surface—flatten out in Coors Field and become easier to hit. It’s a series of interlocking nightmare conditions that compound to make pitching there incredibly difficult.

Which is not to say the Rockies haven’t invested heavily in young pitchers in the past decade. Freeland and Gray were both top-10 picks. So was Riley Pint, a hard-throwing high schooler whom Colorado drafted fourth in 2016, seemingly to try to combat the curveball issue. Then, with their second pick in 2016, the Rockies picked University of Georgia right-hander Robert Tyler, who showed an upper-90s fastball and a plus changeup in his collegiate career.

But neither Tyler nor Pint has made it out of A-ball so far, and Senzatela keeps on chugging along in defiance of convention. Since the start of the 2017 season, 105 pitchers have thrown at least 300 innings in the majors; among those, Senzatela is fourth from the bottom in strikeout rate at just 15.5 percent.

Despite his low strikeout rate, Senzatela is neither an elite command-and-control guy (last year he walked more than four batters per nine innings), nor an elite ground-ball guy (though he is in the top 20 in ground ball rate in the past four seasons). As a result, his numbers are subject to wild fluctuations based on the quality of contact he gives up. In his rookie season, Senzatela induced a lot of soft contact and posted a 108 ERA+ in 134 2/3 innings. Last year, however, Senzatela allowed hard contact on 44 percent of batted balls, according to Baseball Savant, which landed him in the bottom 4 percent of MLB pitchers. His walk rate jumped up, his HR/FB rate nearly doubled from 2018 to 2019, and his strand rate went through the floor to 62.9 percent, or 125th out of the 130 pitchers with at least 100 innings. Somewhat unsurprisingly, Senzatela’s ERA climbed from the mid-4.00s in his first two years to 6.71.

Senzatela has won both of his starts so far in 2020 and allowed just three runs while striking out nine batters in 11 innings. He probably won’t keep that pace up all year, but the Rockies don’t need him to. With Freeland and Márquez at the top of the rotation, all the Rockies need from Senzatela is bulk innings. That much he’s always been able to provide, even when bigger names have faltered.

Jon Gray

In 2017, the Rockies made the playoffs for the first time since 2009, and they tapped Gray, then 25 years old, to start the wild-card game. (The assignment spoke volumes about Gray’s achievements that year, but the less said about that particular game the better.) By the middle of 2018, however, Gray had been optioned to the minors, just as Freeland would be a year later. Unlike Freeland, however, Gray’s underlying numbers still looked good, and he came back to right the ship: a 4.37 ERA in 14 starts after he was recalled to the majors, then a 3.84 ERA in 150 innings in 2019, good for a rotation-leading 135 ERA+.

Gray probably isn’t the no. 1 starter the Rockies hoped he would be when they drafted him third in 2013. But he’s continuing to evolve. His best tool coming out of college was his fastball velocity, but that’s given way to a heavy emphasis on the changeup this year.

Gray made a point to develop a more substantial changeup after lefties hit .272/.361/.457 against him in 2019, while right-handed hitters hit just .248/.298/.421. And sure enough, in just three starts this season, Gray’s already thrown half as many changeups as he did in 25 starts last year.

None of these pitchers are performing at a new level, but the big question for the Rockies’ rotation is consistency, rather than talent. How sustainable is this?

Well, if one were to look for a common trend between these four pitchers in the season’s first two weeks, two things come up. First, these pitchers are all throwing way more changeups than they did last year; second, they all have outrageously low opponent BABIPs. The latter indicates, perhaps unsurprisingly, that the Rockies might not sustain a .750 winning percentage all season, and that they might not end the year allowing roughly as many runs per game as the 1971 Orioles.

But they don’t need to be that good. Or even as good as the Dodgers’ or (when healthy) the Nationals’ rotations. This group is clearly good enough to get to the playoffs and to scare any opponent in a three-game first-round series. Beyond that, it’s tough to say, and a lot will depend on what the Rockies can rustle up behind Senzatela. The one pitcher outside this group to make a start for Colorado this year is Chi Chi González, who allowed three runs in three innings in his only appearance.

The Rockies probably won’t stay ahead of the Dodgers until the end of September. (Or even the end of August.) But they’re six games over .500 in a season when .500 will probably be good enough to make the postseason. And while I still have concerns about the offense, this rotation is undoubtedly playoff-quality. When Márquez and Gray have struggled in the past few years, it’s been for strange reasons, and while Freeland’s disastrous 2019 had a clearer cause, he seems to have fixed what ailed him last year.

We’re finally seeing what the Rockies’ talented stable of homegrown pitchers can do when they’re all on their game. And it turns out that’s launching Colorado into first place.

All advanced stats current through Wednesday’s games.