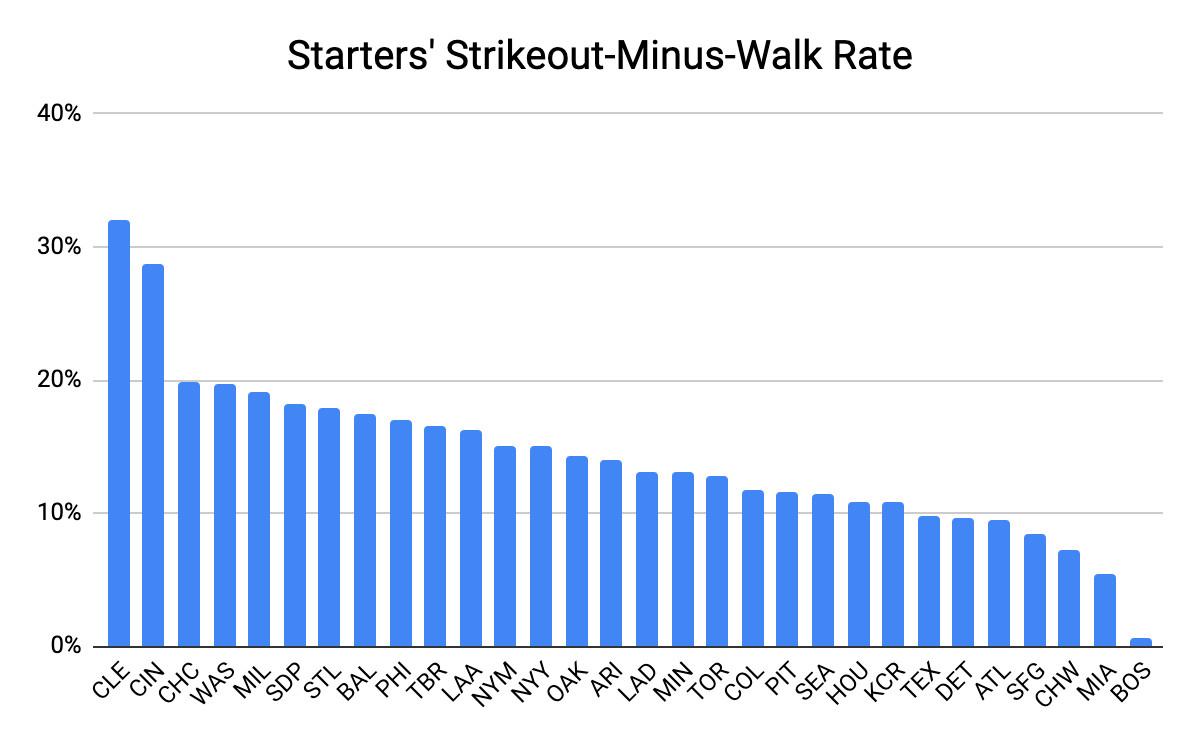

Boston’s rotation is terrible this season, maybe the worst in the majors. The team’s starters rank last in ERA (6.69), FIP (6.58), and strikeout rate (13.8 percent), and are thus the greatest reason for the team’s 3-7 start. In strikeout-minus-walk rate, an important underlying stat, the Red Sox are in last place by a massive margin.

The culprits are all unfamiliar faces. Four Red Sox threw 100-plus innings in each of the past two seasons—but none of them will toss a single pitch for Boston this year, each for a different reason. Chris Sale is out recovering from Tommy John surgery. David Price is a Dodger (and is sitting out the season due to coronavirus concerns), after shipping cross-country as part of the Mookie Betts trade. Rick Porcello signed with the Mets in free agency after his worst season in Boston. And Eduardo Rodríguez, the de facto ace of the staff with Sale hurt and Price gone, was officially ruled out for the season over the weekend due to a heart ailment resulting from a bout with COVID-19.

Yet Rodríguez’s absence is not a mere obstacle with which the reeling Red Sox, now in last place in the AL East after a weekend sweep in the Bronx, must contend. His is not a story to append to a broadcast graphic explaining the rotation’s troubles, a vacancy on par with Sale’s unfortunately run-of-the-mill elbow injury or Price’s departure by trade. As MLB confronts its continued inability to stem the spread of the coronavirus—outbreaks among the Marlins and Cardinals; schedule interruptions for the Phillies, Nationals, Yankees, Orioles, and Brewers; in-season opt-outs from veterans Lorenzo Cain and Yoenis Céspedes—the pitcher sidelined for the season due to lasting effects of the virus stands as a stark reminder of the season’s actual stakes.

Rodríguez’s path to a prospective Opening Day start was a decade in the making. He signed with the Orioles out of Venezuela in 2010, then made his way to Double-A in the Baltimore system before going to Boston at the trade deadline in 2014, as the playoff-bound Orioles traded for Andrew Miller from their division rival. He debuted for Boston in May 2015 with 7 2/3 shutout innings—one of the best career openers for any pitcher in franchise history.

For the next four seasons, Rodríguez was a stable if not spectacular mid-rotation starter, good for 20-plus solid starts a year. And in 2019, the 26-year-old experienced a breakthrough: He was one of just 15 pitchers to throw at least 200 innings last season, while retaining his per-inning effectiveness. His park-adjusted ERA was 26 percent better than the league average, a career best; he won 19 games and tied for sixth in AL Cy Young voting.

So with the rest of the rotation’s exodus, Rodríguez was set for Boston’s delayed Opening Day start—only to be diagnosed with COVID-19 in July. The virus hit the pitcher hard. “I felt like I was 100 years old,” he told reporters afterward. “My body was tired all the time. Throwing up. Headaches. Like I said, all the symptoms.”

“I’ve never been that sick in my life, and I don’t want to get that sick again,” he added. Rodríguez’s experience sounds a lot like that of Atlanta star Freddie Freeman, who said he prayed for his life while sick with COVID-19, which induced a 104.5-degree fever. “I’ve never been that hot before,” Freeman said.

Rodríguez’s symptoms eventually abated, and he hoped to make a full return to the mound, if not by Opening Day then early in this abbreviated season. But he grew inordinately tired after throwing just 20 pitches in a bullpen session, and the Red Sox delayed his return for further testing. On July 23, Boston manager Ron Roenicke said “everybody” was confident that Rodríguez would recover sufficiently to pitch this season. That assessment was contradicted the very next week: Rodríguez was shut down for the season after a diagnosis of myocarditis, an inflammation of the heart that “weakens the heart, creates scar tissue and forces it to work harder to circulate blood and oxygen throughout the body,” according to the Myocarditis Foundation.

“We were optimistic that it would resolve in short order and that we would be progressing back to pitching,” Red Sox chief baseball officer Chaim Bloom said. “As we’ve continued to monitor it, it has not resolved. It is still there.”

The novel coronavirus is just that, novel, which means researchers are only beginning to learn about its potential long-term effects. As one virologist told The Washington Post in a piece about the virus’s body-spanning impact—“Often it attacks the lungs, but it can also strike anywhere from the brain to the toes,” the Post wrote—COVID-19 is “just so new that there’s a lot we don’t know.”

Some early results are concerning, however, particularly with regard to the heart. One study of 100 recovered COVID-19 patients in Germany found that 78 percent of them showed evidence of heart damage, including 60 percent who showed “ongoing myocardial inflammation … independent of preexisting conditions, severity, and overall course of the acute illness.”

Even if patients don’t notice any issues with their heart as the virus runs its course, they may still suffer damage there. Rodríguez told radio station WEEI he was surprised by his myocarditis diagnosis because “I don’t feel any symptoms from that, I didn’t feel anything from my chest, nothing like that.”

Other organs, from the lungs to the kidneys to the brain, have also been implicated in various COVID-19 complications. The long-term effects on the body are still unclear, but the virus’s early ripples are discouraging. A coauthor of the German study, cardiologist Valentina Puntmann, told UPI, “While we do not yet have the direct evidence for [long-term] consequences yet, such as the development of heart failure, which can be directly attributed to COVID-19, it is quite possible that in a few years this burden will be enormous based on what we know from other viral conditions.”

Long-term heart and/or lung problems could ruin a professional athlete’s career. The Myocarditis Foundation recommends that patients “avoid competitive sports and other rigorous exercise.” Rodríguez should be able to pitch again eventually; Bloom says he’s hopeful his pitcher makes a full recovery and that “his long-term prognosis is excellent.” But the very fact that he has to miss a season in the meantime speaks to the virus’s far-reaching effects—plus there is no certainty in a recovery at this point, despite the club’s optimism. Myocarditis following COVID “is obviously not something that the medical community has a lot of data on because the virus itself is new, much less in an athlete,” Bloom says.

That uncertainty is the point—the reason it’s impossible to hand-wave COVID-19 cases for otherwise healthy, young athletes because they’re not in the most vulnerable demographic groups. The long-term effects on both person and profession are still to be determined. And it’s impossible to think about, on a micro analytical level, the woeful state of the Boston rotation without reflecting on the biggest hole in the center, and why it’s there; the virus remains a central component of every corner of the MLB universe.

It’s also impossible to think about, on a macro level, the rest of this season, with news of positive tests arising seemingly every day, without considering Rodríguez. The 27-year-old lefty just wanted to pitch, and to build on his breakout season. Now he’s shut down for the year with a heart condition, and hoping for a return to health before he can even contemplate a return to the mound.