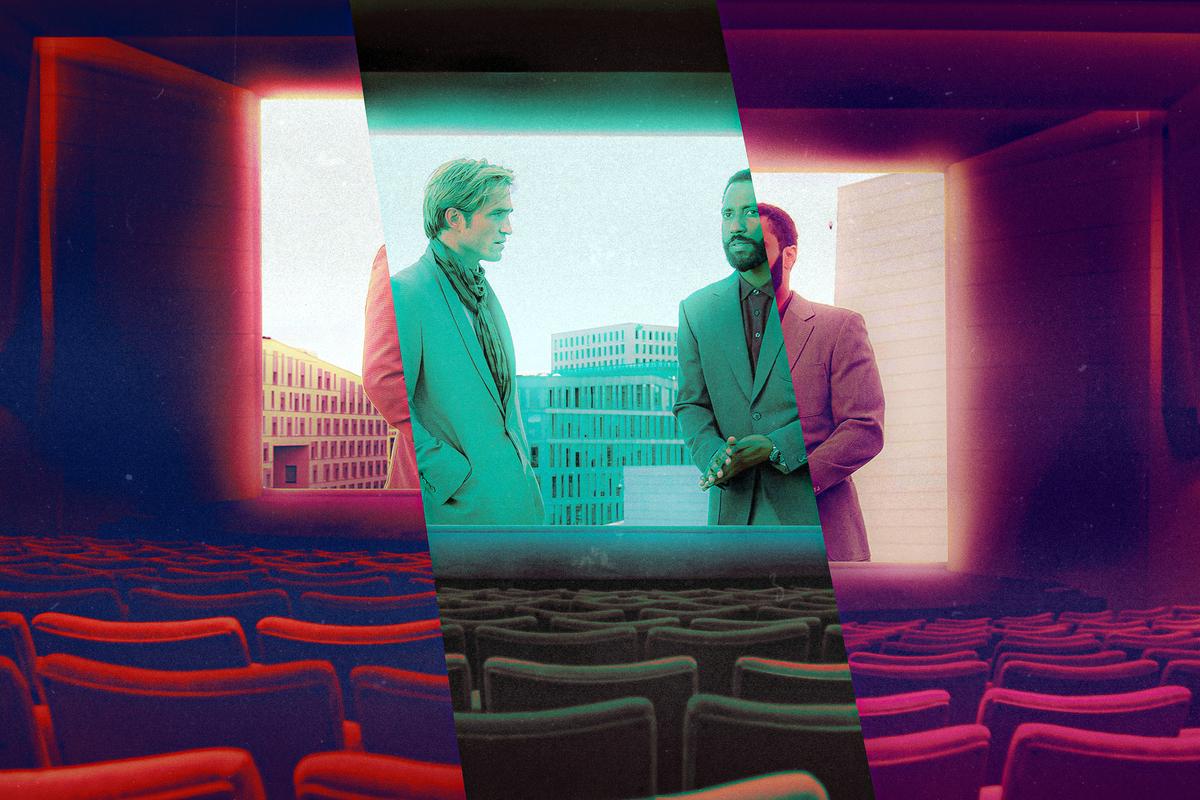

‘Tenet’ Is Coming to a Theater Near You. Eventually. Or Maybe Not. Or Maybe Much Later Than in Other Places.

After multiple postponements, Warner Bros. indefinitely delayed the release of Christopher Nolan’s latest film on Monday. What the studio chooses to do next might have paradigm-shifting potential.

In another timeline we’ve already seen Christopher Nolan’s Tenet. In all likelihood, we’ve just spent the better part of a week discussing it, arguing about it, and trying to figure out exactly what it means. Nolan’s been typically tight-lipped about the film, revealing as little about its premise as possible, but in the world where it made its original release date of July 17, its secrets already have been revealed. But that’s not our world. In our world its release date keeps shifting. On Monday, Warner Bros. changed the release date for the third time, prompting Slate’s Dana Stevens to quip, “We will never not be just about to see Chris Nolan’s Tenet.” What if she’s right? Is it possible we’re stuck in a timeline in which this movie keeps almost being released only to be yanked away, like Lucy’s football? Or maybe it will become, like the Great Pumpkin, an article of faith. We’ll never see it, but we can take comfort in believing it exists.

Warners first moved Tenet from July 17 to July 31, then to August 12, each date presumably selected based on the likelihood that the film would be able to play widely in theaters across North America and the rest of the globe. This latest shift, however, is different. Instead of supplying a new release date, Warners has promised only an announcement of a future date.

For a while it looked like Tenet’s release could signal a return to normalcy, at least when it came to moviegoing; that the date of that return was previously only being pushed back by a few weeks was an encouraging, if odd, symbol. Now that date has completely retreated from view, possibly taking the old idea of normalcy with it. “We are not treating Tenet like a traditional global day-and-date release, and our upcoming marketing and distribution plans will reflect that,” Warner Bros. chairman Toby Emmerich said in a statement. Unnamed Warners insiders further clarified by suggesting to Variety that Tenet could open in other parts of the world before making its North American debut. Even then, it might not be business as usual, with the same insiders suggesting Tenet “could move forward in select U.S. cities where cases of the virus have eased and public health and government officials deem it safe.”

So much for normal. But even beyond the staggering nature of this potential future, the simple question remains of whether it could work. Take Tenet out of the equation for a moment and just consider the implications of a release strategy in which a major motion picture doesn’t blanket the globe all at once, but instead travels from region to region. This is more or less what the National Association of Theatre Owners is advocating for now. Speaking to Variety in the wake of the Tenet delay announcement, NATO CEO John Fithian asked Hollywood to “stick with their dates and release their movies because there’s no guarantee that more markets will be open later this year. Until there’s a vaccine that’s widely available, there will not be 100 percent of the markets open. Because of that, films should be released in markets where it is safe and legal to release them and that’s about 85 percent of markets in the U.S. and even more globally.” In other words, films should open now where they can, and wait until later to open elsewhere.

But this “solution” skirts around several issues. Fithian notes that theaters are safer than bars, but “safer than” isn’t the same as “safe” and there’s been much confusion about both what it would take to make moviegoers secure and what it’d take to make them feel secure at the movies again. That AMC and other major chains initially announced that they would not require patrons to wear masks didn’t inspire confidence. Nor, for that matter, does a pending lawsuit—initiated by major chains—demanding the reopening of New Jersey theaters against the will of the state’s governor. It’s hard to see the attempt to override the mandate as anything but an extension of the rush to reopen that’s led to the current surge in cases in the United States. In fact, a surge in cases recently forced California to close theaters previously deemed safe.

But even if theater owners manage to agree on a universally accepted set of safety protocols and we reach a better understanding of when it’s safe to go to the movies, the fact remains that some countries—and even in the U.S., some cities—are further along in the response to COVID-19 than others. And because it’s becoming increasingly clear that both distributors and exhibitors don’t want to—or financially can’t—wait until the world is 100 percent free of the virus, a new model for releasing movies could emerge and become the norm. That model, however new-sounding it is, actually resembles an older model, one that was still used by smaller releases before the spread of the coronavirus.

Wide releases for major studio films became the norm only in the past 40 years. Like most developments in the world of blockbuster moviemaking, the wide release’s origins can be traced back to Jaws, which didn’t invent the strategy of saturation booking—opening a film on many screens at once—but did confirm that the right movie released at the right time could be profitable on a scale previously unimagined. Where wide releases had been treated like cash grabs for disreputable fare—attempts to use ubiquity and heavy advertising to make a lot of money quickly before bad word of mouth spread—Jaws proved that the approach could create cultural phenomena. As the ’70s turned into the ’80s, the tactic became standard.

But it wasn’t the only possible approach. A kind of high-water mark for big-budget genre movies, the summer of 1982 saw the debuts of E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, Poltergeist, Blade Runner, and The Thing. It also saw the release of The Road Warrior, George Miller’s first sequel to Mad Max. Already a hit elsewhere in the world under the title Mad Max 2, The Road Warrior played in New York in April as part of the New Directors/New Films series but didn’t return to the city until August 20, as part of a second wave of release that brought the film to the East Coast. By then, it had already played most of the country a few hundred theaters at the time, picking up strong reviews and positive word of mouth along the way. The savvy approach helped assure that a potentially tough sell—a sequel to an Australian movie that hadn’t been a hit in the U.S., led by a then-relatively anonymous Mel Gibson and helmed by a director virtually unknown to American moviegoers—would find an audience.

That approach—one that major studios may eventually be forced into adopting—could theoretically still work in 2020, but it would have to take into account the many ways the world has changed since the release of The Road Warrior, and Tenet doesn’t make a reassuring test case for its possible success. Still shrouded in mystery, its secrets would last only as long as it took for its first viewers to log onto Twitter during the closing credits (assuming they waited that long). Once viewers in, say, Montana learn that John David Washington’s character is actually a ghost, will people in San Francisco waiting for the movie to be released still want to see it? (Note: John David Washington’s character is probably not a ghost.) Granted, spoilers’ ability to impinge on a film’s success probably has been overstated, especially since secrets never survive opening weekend in normal times. Piracy would be the more pressing concern. It’s easy to see the unavailability of a film like Tenet driving up demand for torrents in markets where it is not yet available—and to see that those kept away by the pandemic find downloading it illegally more justifiable than before. After all, life in a hot zone is hard enough—aren’t you allowed a little copyright infringement without thinking of the legal and ethical implications and the ripple effect such a choice has on an already-struggling industry? There’s also the question of how the press would cover regional releases. Will national publications be interested in covering films that might not play the coasts for weeks, even months? And with the gutting of local newspapers and alt-weeklies, are there even enough regional critics and entertainment journalists to cover a movie only being released in Denver? (An overly optimistic flip side to that question: What if this new release format reinvigorates the culture pages of local newspapers?)

The only thing clear at this point is that nobody knows exactly what will happen next. After the announcement that Tenet would be delayed indefinitely, Texas Monthly writer Dan Solomon shared an email from Warners in which an unnamed studio rep stated, “We’re rewriting the playbook in real time” and “every factor is in play” including “international, domestic, and regional scenarios” that will “allow audiences to discover the film in their own time, and we plan to play longer, over an extended play period far beyond the norm, to develop a very different yet successful release strategy.”

Tenet’s original release date was no accident. It resulted from a calculation that considered Christopher Nolan’s track record and previous success in releasing cerebral-yet-visceral action films in the heart of the summer. The pandemic not only destroyed that plan, it upended the entire system around it. For a while, Tenet’s release looked like a beacon signaling a return to business as usual, but the movie world in which it was scheduled to appear might never come back. The world that takes its place will come with a whole new set of rules for how a blockbuster is released.

Keith Phipps is a writer and editor specializing in film and TV. Formerly: Uproxx, The Dissolve, and The A.V. Club.