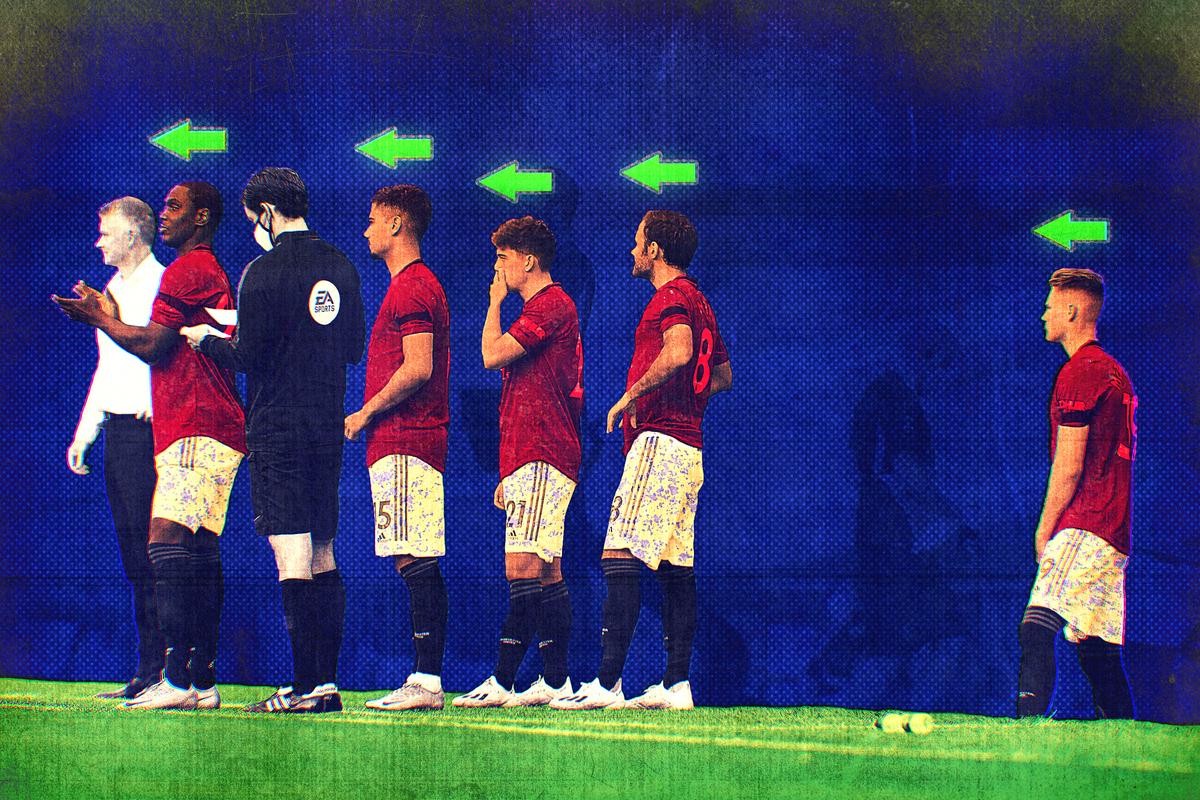

In the 80th minute of Manchester United’s 3-0 Premier League win over Sheffield United on June 24, soccer became basketball when Manchester United coach Ole Gunnar Solskjaer made five substitutions at once. This would be called “clearing the bench” in the NBA; that is to say, when you are beating the opposition by such a large margin that you send in the reserves and give all your main players a rest. Solskjaer probably did not make this decision for historical reasons, but in a tactical sense it felt as momentous as the first time a human set foot upon the moon. It felt this way because soccer is most definitely not basketball. Until the arrival of the pandemic and the introduction of five substitutes rather than three, you could generally not make changes that radically altered a soccer team’s on-field makeup. Basketball, on the other hand, allows unlimited substitutions, and the sport is arguably all the more dynamic for it.

Looking at the careers of some of soccer’s most daring coaches, you sometimes wonder whether they ever have been secretly jealous of the freedoms long enjoyed by their basketball counterparts. Marcelo Bielsa is widely acknowledged as one of the game’s geniuses, someone whose approach has been taken and perfected by managers with far greater resources, and whose influence—constant pressing, swift movement of both players and ball, astonishing speed on the counterattack—can be seen in leading teams all over the globe. Yet the man who Pep Guardiola himself has hailed as “the best coach in the world” has never won a first division title in Europe.

That is not because Bielsa is not brilliant; it is because he is exhausting. Guardiola implied as much in 2011 after an astonishing tie between his Barcelona side and Bielsa’s Athletic Bilbao, when he observed that “they deny you space and time so well, and they take you on, one on one, all over the pitch. They’re beasts. I have never played against a team so intense.” It is simply not sustainable in a game with only three replacements to play an entire season at that level of physical exertion. But with five? What more could Bielsa’s teams have achieved then?

Years earlier, another coach operating in Spain tried to make soccer into basketball. Javier Irureta, during his brilliant years at Deportivo La Coruña, assembled a squad so good that at one point the replacements were almost as good as the starters. He could take off Roy Makaay and replace him with Diego Tristán, one of the best strikers in Europe at the time, or swap Djalminha for Juan Carlos Valerón, one of the greatest playmakers of his generation. Yet this, too, was unsustainable. Tristán felt slighted by Irureta’s refusal to start him more regularly despite his outstanding form, and the effect upon his confidence was terminal.

It is tempting, then, to imagine a soccer world that permanently has five substitutes: where a player like Tristán can get far more playing time and be consistently devastating from the bench. In the modern era, he might be more like Manu Ginobili was for the San Antonio Spurs, a superstar who began so many games on the sideline but who was brought on to provide their decisive moment. Maybe soccer could converge not only with basketball but with some of the other American sports, and fully embrace the concept of the specialist. In the future, we might see midfielders whose job is similar to that of the closer in baseball, where their only responsibility is to come on at the end of the game and preserve a lead. (This was the manner in which the great Xavi was used toward the end of his career with Barcelona.)

On the question of whether soccer should increase its substitution count, there is one strong argument for and one against. In a positive sense, it could help cut down on injuries. The rule allowing a maximum of three substitutes was introduced at a time when medical professionals might not have envisaged the remarkable strain. The modern player is faster, stronger, and fitter than they were a generation ago, and perhaps therefore more prone to muscle fatigue than in those years past.

Conversely, though, there is the fear that increasing the number of substitutes would be overwhelmingly beneficial to wealthy teams—that is to say, those who can easily afford the squad depth of which Marcelo Bielsa has perhaps secretly dreamed. Recently, watching Manchester City’s fleet of replacements waiting by the edge of the pitch, I had a grim thought: of rich clubs simply stacking their sides with elite talent, so that endless hordes of super-fit and world-class players would keep storming forth from the bench and hammer poorly resourced teams out of sight. Maybe, in that universe, the FA Cup Final between Manchester City and Watford—where Kevin de Bruyne came on to claim the man-of-the-match award in just 38 minutes—was a foreshadowing of the future. That’s a reality I don’t want to imagine, and one that is already uncomfortably close; if and when soccer does more closely resemble basketball, it will only mean that the rich are able forever to dunk on everyone else.