“The Trivia Is Exceptional”: The Making and Disappearance of Don DeLillo’s ‘Game 6’

The novelist’s only screenplay turned the 1986 World Series into a backdrop for an unusual comedy about anxiety, failure, and fandom—but a rough release doomed it to obscurityAfter years of being held out of distribution and facing the fate of being lost to time, Game 6—the only feature-length film ever written by Don DeLillo—will officially see the light of day and hit VOD on August 10. Before you watch it, read Ross Scarano’s feature, originally published in July 2020, on how the movie came to be buried in the first place.

Execs at Universal Pictures had reviewed the screenplay and come to a decision: They could not abide the dead cat.

See, in the movie’s climax the protagonist, pushed beyond his rational limit, enters his enemy’s derelict loft apartment on the West Side Highway, gun in hand, and starts shooting. After an hour-plus of anxiety and whispers of gunplay, here it is, the eruption the picture was always racing toward: Shots ring out in the dismal studio, whizzing past the chemical toilet, punching drywall, shattering glass into twinkling pieces. And then the shot that mows the cat down, the pet caught in the crossfire and struck dead. Imagine the screech and the bloody fur. Inside the meeting, Universal demurred. It was the sole note offered to the first-time screenwriter and his producing partners, who had flown from New York to Hollywood just to hear the studio’s assessment of this new project, entitled Game 6. We don’t think the cat should get killed.

Of course, this particular screenwriter was a Guggenheim fellow and a recipient of the National Book Award. A Bronx native in his 50s, critically acclaimed for his novels of uncanny consumerism and nuclear-age malaise, he had an outsized reputation for his low profile. He sat for only as many interviews as he had to, refused to appear on TV, and would never be a regular on any Los Angeles lot. In an interview conducted a few years before this meeting, when asked about the film producers who inevitably came calling after his work, he replied, “Usually someone in a borrowed office phones up and says, ‘You know, Great Jones Street, boy that’s somethin’. Wow, let’s have lunch.’” In other words, this was an improbable occurrence. All the same, Universal had its convictions. The cat had to live.

To understand how Don DeLillo arrived in Hollywood to receive a note about a dead cat, you might as well begin with a bachelor party among a crew of New York intellectuals made memorable by a bad review. It was the summer of 1990 and Hamilton Fish V, then the publisher for The Nation, was getting married. The producer and actor Griffin Dunne, star of Martin Scorsese’s madcap classic After Hours, was in attendance, along with the writer and editor Victor Navasky and cartoonist and playwright Jules Feiffer. What should have been a pleasant celebration of Fish’s upcoming nuptials went sideways because of Feiffer’s hurt feelings. His latest play had been knifed in The New York Times by Frank Rich, the fearsome theater critic known as “the Butcher of Broadway.” Rich’s last line compared the experience to a mugging.

“Jules dominated the conversation because he was so upset about this review,” Dunne tells me. “He went on this stream-of-consciousness rant about kidnapping Frank Rich, keeping him locked in a closet or something.” Over a decade into his producing career, Dunne recognized that Feiffer had inadvertently handed him something good. Back at the office he dished to his producing partner, Amy Robinson. What a funny idea for a movie, right?

As if summoned, Don DeLillo entered the office via fax machine.

The device whined to life and spit out a movie treatment via DeLillo’s agent. It would be the first of many coincidences surrounding Game 6. “It was about this Red Sox–loving playwright who goes on a vendetta against a critic on the opening night of his new play, which coincides with Game 6 of the 1986 World Series,” Dunne says. The double-barreled anxiety of sharing new, highly personal work, plus the masochistic burden of sports fandom, set in traffic-clogged Manhattan. A frazzled playwright, an unorthodox theater critic, Bill Buckner stooping for the grounder at first. There was a street-clearing asbestos explosion, reminiscent of the airborne toxic event in White Noise, the novel that won DeLillo the National Book Award. And of course there was baseball, a subject close to the author’s heart, a love he’d kept since boyhood. “The idea was funny and dark and very DeLillo. So there it began.”

For nearly 15 years that was all it did: begin, over and over and over. The project cycled through directors—Neil Jordan, Robert Altman, and Gore Verbinski were all interested at various points—but couldn’t get made. The conditions weren’t right. Jordan, for instance, didn’t have the clout to push it through when he was involved, prior to The Crying Game, and Altman wanted Steve Martin in the lead, but, according to Robinson, Martin didn’t want to do it.

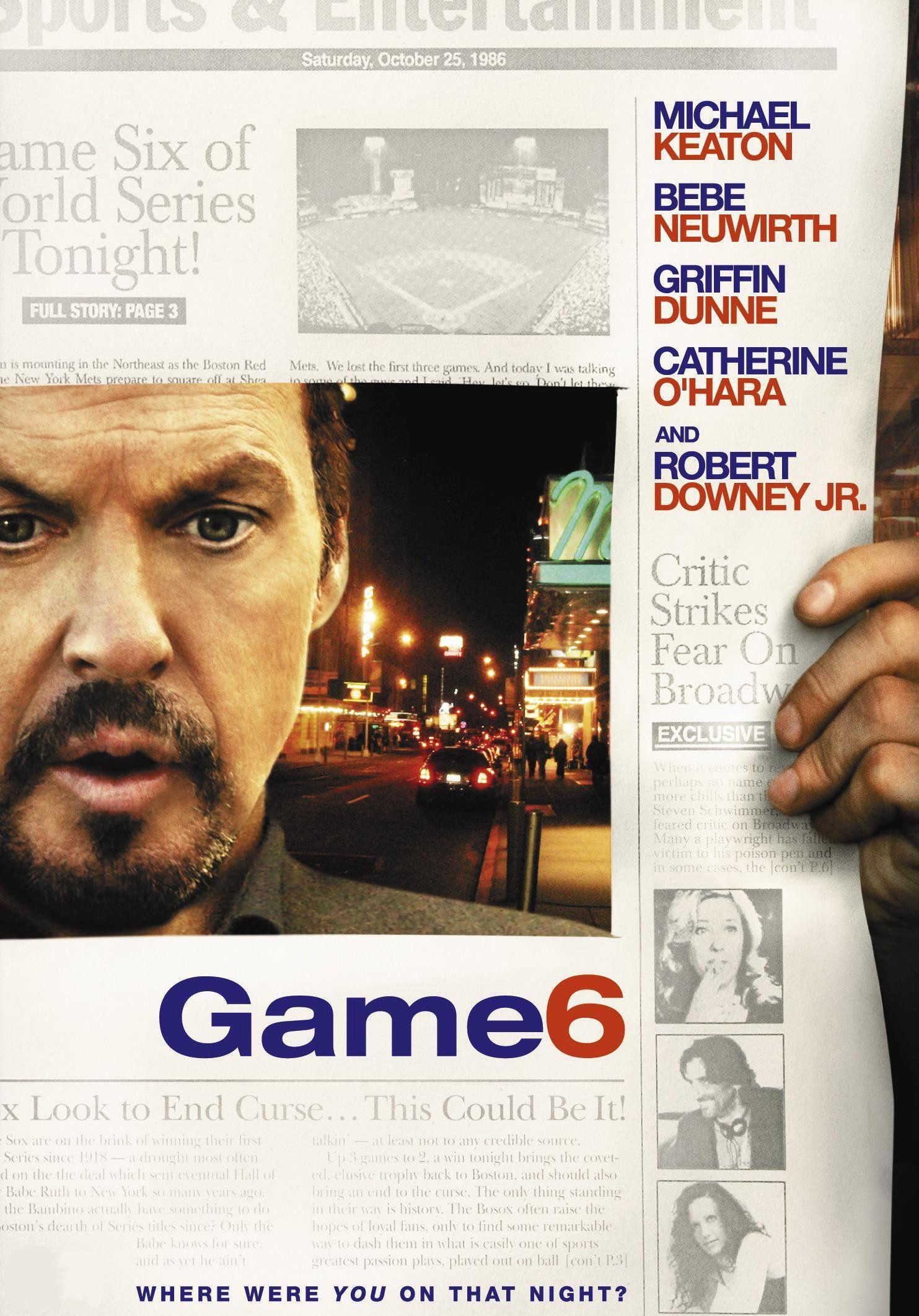

When it finally happened, as an indie directed by Michael Hoffman, with a cast that included Michael Keaton, Robert Downey Jr., Catherine O’Hara, Bebe Neuwirth, Ari Graynor, and Dunne, Game 6 suffered an unfavorable rollout. After premiering at Sundance in 2005, the movie opened on a handful of screens in March 2006 before practically disappearing. The only film written by one of the most celebrated and influential figures in American letters, a perennial contender for the Nobel Prize in Literature, isn’t available to stream on Amazon or Hulu or Netflix or HBO Max or the Criterion Collection. For most people in 2020, Game 6 does not exist. A movie’s journey from creation to audience is beset with all sorts of obstacles, illustrating just how vulnerable the ecosystem of movie viewership really is. The story of Game 6 is an object lesson in just that.

In the late 1970s, Robinson and Dunne turned to producing after struggling to find work as actors. Robinson had success in the early part of the decade, playing Teresa, the female lead, in Scorsese’s Mean Streets, and Dunne had appeared in a weepy ski-accident drama in 1975 called The Other Side of the Mountain. “When Amy and I met, before we ever thought we’d produce movies, we bonded over books,” Dunne says. Avid readers of The New Yorker, they would talk about the magazine’s short fiction, and Robinson hipped Dunne to a young writer she admired named Ann Beattie. Along with a third partner, the actor Mark Metcalf, they decided to try to adapt Beattie’s 1976 debut novel, Chilly Scenes of Winter.

The trio learned that Beattie was teaching at Harvard, so they made the four-hour drive from New York to Cambridge. “We called her from a phone booth and she invited us over. She said it was like three of her characters walked into her living room,” Dunne says. They made a deal for $2,000. “Ann talked her literary agent into giving us the rights for very little money—with the promise that she would have a walk-on part as a waitress with a beehive hairdo. This outraged the agent, but we got the rights.”

The film adaptation was released in 1979; Robinson and Dunne had found a new calling—and made an important friend. Beattie introduced the duo to a writer friend of hers, Don DeLillo. The pair read Great Jones Street, his 1973 novel about a mysterious rock star—perhaps they’d find a way to work with him too.

A little over a decade later the fax machine whirred, signaling that it was time. “More than they do now, the studios gave what’s called an overall deal to producers,” Robinson explains, and the expectation was that these trusted producers would regularly bring viable material to their studio execs. At the time Robinson and Dunne had such a deal with Universal Pictures, and they convinced the studio to take on the first screenplay from the writer who had recently published the best-selling Libra, an unsettling and poignant depiction of Lee Harvey Oswald. It was the beginning of the Miramax era, after sex, lies and videotape alerted the motion picture industry to the potential profitability of cheaply made, idiosyncratic material. The studios were tentatively more interested in outré material after a decade defined by sequels and Stallone. The studio paid DeLillo to write Game 6 and by 1991 he’d finished a draft. Universal called the meeting.

Game 6 covers a challenging day in the life of Nicky Rogan, a playwright successful because of his broad comedies but beset by sundry problems: His daughter’s pissed at him for cheating on her mom, his wife is likewise angry, and in his bones he knows that his beloved Boston Red Sox are going to lose to the New York Mets. He’s debuting a new play, a personal work that draws on his threadbare, five-in-an-apartment New York childhood, but the lead actor can’t remember his lines because a parasite he picked up traveling in Borneo is chewing a path through his brain. And Steven Schwimmer, dubbed the “Phantom of Broadway,” is somewhere out there, preparing to review the new play. Word is, it’s going to be a bloodbath. Much of Rogan’s day is spent riding in cabs, sitting in traffic, and making idle conversation with strangers as a distraction from the inevitable. Because it’s a period piece, the viewer can’t help but see failure at every turn—it’s October 25, 1986, a mild day fated to turn real ugly. The Curse of the Bambino. That day the Boston Red Sox were up 3-2 in the World Series—but Rogan knows that true fandom isn’t about winning. “We have a rich history of interesting ways to lose a crucial game. Defeats that keep you awake,” he says at one point, with relish. He’s a connoisseur of losing, and in a few hours he’ll get to watch first baseman Bill Buckner miss a Mookie Wilson ground ball in the bottom of the 10th inning.

“Griffin and I took Don out to Hollywood, and he was not too happy about that,” Robinson says. “Don’s a novelist and lives his own life. I mean, it wasn’t this terrible thing—he came, we went out to dinner. I just don’t think it was something he wanted to spend his time doing. But he did it.” If you’ve assumed it’s because DeLillo wanted to see his movie get made, you’re wrong. “I don’t think he really cared about that. … I don’t think Don needed to get this movie made. He had an idea and he sent it to us because he knew us.” And then Universal asked him to spare the cat. (“I don’t believe the movie studios ever want to see a house pet shot,” Robinson says.)

“I’m afraid that I have only the dimmest memory of meeting with Universal,” DeLillo says via his agent. But practical and willing to be flexible, he took the note. In the final draft, the playwright shoots a photo of the critic holding his cat instead.

In interviews preceding Game 6’s inception and after its writing, DeLillo does not mention his screenplay. He conveys little interest in moviemaking, least of all in adaptation. “People have taken options and written screenplays, but I’ve never wanted to write screenplays for my own books,” he told the Canadian lit mag Brick in 1988, during the Libra press run. (His masterpiece Underworld, which opens with Game 3 of the 1951 National League tie-breaker series between the New York Giants and the Brooklyn Dodgers—the historic “Shot Heard ’Round the World”—was optioned by producer Scott Rudin in 1996, before it was published. The novel is 832 pages long and has yet to be adapted.)

He’s a viewer, and even then he locates his purest enthusiasm in the past: “Probably the movies of Jean-Luc Godard had a more immediate effect on my early work than anything I’d ever read,” he says in his first interview, published in 1982. (By then, he had been working as a novelist for over a decade.) From the Brick interview: “I was a very avid filmgoer through the sixties. That was my personal golden age of movies: Bergman, Antonioni, Godard, and several other people. I haven’t been nearly so enthusiastic since those days.”

Waning enthusiasm or not, he still watches. Across the decades, in interviews and a short 2003 New Yorker essay about film and memory, DeLillo has mentioned Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather and Apocalypse Now, Harmony Korine’s Gummo, Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, Claire Denis’s Beau Travail, and Matthew Barney’s Cremaster 5. Blockbusters, arthouse fare, genre pictures, French cinema, the avant-garde. Movies and the power of the image are recurring subjects of inquiry in his novels, starting with his 1971 debut, Americana. “Movies can shape a layer of memory, leading us into a shared past, sometimes false, dreamlike, childlike, but a past that we’ve all agreed to inhabit,” he wrote in The New Yorker. At one point, he decided to participate more actively in the construction of that comprehensive layer, writing a movie of his own. But unlike the handful of plays he’s written between novels, Game 6 went over a decade without being produced. The screenplay became, for a time, a ghost in his bibliography, seldom discussed but widely read. “This was before the Black List,” Robinson says, “but the script really did float around. A lot of people read it.”

The meeting of the dead cat was an omen, unsurprisingly. “They were completely mystified by the script,” Robinson says of Universal. Though they’d initially expressed interest in the idea, it became clear that “they were obviously not going to make the movie.” Eventually, Universal relinquished the rights to the story. “It’s not uncommon to put a lot of energy into something as the producer,” Dunne says. “You develop it, you go through rewrites, and you get dragged along by the studios, only to have them decide, ‘We don’t really want to do this.’ After all that effort, you just let it go and forget about it.”

In a 2006 interview, DeLillo admitted the same thing: “In fact, I forgot about it totally.”

Meanwhile, in Idaho, Michael Hoffman needed to buy tile. He and his then-wife were building a house in Boise, where he had attended college. They met with their contractor at the tile store to assess options. By then Hoffman had moved from directing Sundance-approved indies to multimillion-dollar studio fare, like 1991’s Soapdish. A caffeinated backstage comedy, Soapdish introduced Hoffman to Robert Downey Jr., the start of a friendship that led to 1995’s quirky period picture Restoration. (If you’re craving a 17th-century dramedy in which RDJ plays a fun-loving doctor who farts on command and cares for a pack of royal spaniels in between group sex, there is a movie for you. Also starring: Meg Ryan.)

Hoffman and his wife finished their business with the contractor, picked up their house plans, and went out to the car. Settling in, Hoffman glanced down at the plans and in a once-in-a-lifetime moment realized, This is not my beautiful house. He had the wrong plans. The name on these was familiar, but surely it couldn’t be. Hoffman walked back into the store, and there he was, the plans’ rightful owner, standing by the counter, with that mustache. It was Bill Buckner.

“We were all linked in a vast and rhythmic coincidence, a daisy chain of rumor, suspicion, and secret wish,” DeLillo writes in Libra. Coincidentally, Dunne told Robinson the bachelor party story, and the Game 6 treatment arrived the same day. Coincidentally, Hoffman wound up holding Bill Buckner’s house plans years after he first read the Game 6 screenplay but well before he would be attached to direct. There were other coincidences to come.

Around the millennium, Leslie Urdang found herself in Los Angeles in need of a new gig. She’d moved there from New York, where she had worked in theater, to make films with Robert Redford and his production company, Wildwood Enterprises. But the situation changed, leading Urdang to start a production company of her own. She called it Serenade Films and partnered with old New York friend Amy Robinson and Hoffman, with whom she had worked on a movie adaptation of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The idea was to produce films that cost half a million dollars or less, and that every cast and crew member would share in the revenue. For their first picture, they resurrected Game 6. With a network grown over decades and material so strong and unusual, they reckoned they could fill out the cast and crew despite not being able to offer much in the way of upfront compensation.

Before they could begin, Hoffman needed to set his mind at ease. After the tile run-in, he had grown close to Buckner and his family; he understood how Buckner had been “abused” by angry fans after the fielding error that cost the Red Sox the series in ’86. “The rage about that,” Hoffman tells me. “There were death threats.” Hoffman brought the Buckners the script. Confirming his fears, they initially told him they weren’t sure they wanted to reopen this wound. But then, after a change of heart, Buckner told him to go ahead, to make the movie.

Had he not received Buckner’s blessing, Hoffman says that he wouldn’t have done it: “And even though Bill was very gracious about it, I still hope that they were really OK with it.” (Buckner died on May 27, 2019.)

Game 6 shot over 18 days on location in Manhattan in summer 2004. The challenges were myriad: little time to rehearse, little time to shoot, little money to convincingly stage an asbestos explosion in a Manhattan that’s supposed to be Ed Koch’s graffitied metropolis. They had to win tricky negotiations with Major League Baseball for the game footage, and with Shea Stadium to shoot in its hallowed spaces. There were barely enough automobiles to make convincing gridlock. “All those traffic jams were created with like six cars,” Hoffman says. “It was insane.”

There was so little time and money that it became clear the script needed to be trimmed. Hoffman had done it to writers’ scripts in the past, but none of those writers were Don DeLillo. They met at Robinson’s office to explain that a particular sequence wasn’t feasible, and Hoffman says that Don was open to the change. “Don is very pragmatic, very unsentimental, very un-self-pitying,” he says. Curious, too. DeLillo visited the set multiple times and, according to Robinson, he was never obtrusive. Hoffman recalled the company he kept: “He came on set all the time and I’d say, ‘Oh, who’s your friend?’ ‘Oh, that’s Paul Auster.’ ‘Who’s that?’ ‘That’s Gordon Lish.’”

The budget was half a million dollars. “Our budget on Mean Streets was about the same,” Robinson says, laughing, because Mean Streets came out in 1973. With a crew of veterans and little cash for salaries, casting Game 6 relied on relationships and favors. Dunne passed the script to Keaton, who agreed to play playwright Nicky Rogan for $100 per day; the two had been friends since Johnny Dangerously in 1984. Keaton brought a three-legged stool to set because they had no trailers for downtime; he would put it down on the street and talk to strangers in between setups. In a 2006 interview, Keaton told Reuters that he now knew all the public restrooms in New York because they were his hair-and-wardrobe.

Hoffman brought in Robert Downey Jr. to play critic Steven Schwimmer, a somewhat remarkable feat given how little work Downey did then, still recovering from his highly publicized departure from Ally McBeal in the wake of a series of drug arrests. “Coming out of that period, Robert was careful about controlling his environment,” Hoffman says. “He made sure that he took very good care of himself, physically, emotionally, and psychologically. Robert and I had lots of conversations about how to create a safe work environment for him.”

“Whatever he was going through at that time, or in the years preceding, he never held up production,” Dunne says. “It was three or four days of work, and he brought his inventiveness to the performance and was gone.”

Downey is one of the best parts of Game 6. His character is a kind of cracked embodiment of DeLillo’s idea that “the writer is the person who stands outside society, independent of affiliation and independent of influence.” A widely hated theater critic, Schwimmer lives in squalor, constructs elaborate disguises to go out, and carries a gun out of fear for his life. He also appears to be a practicing Buddhist.

In Schwimmer’s early scenes, he has no dialogue and his face is obscured for some of that time by a sleep mask. He whirls around inside his busted loft, accompanied only by the film’s spacey, guitar-driven score—by New Jersey indie rock staple Yo La Tengo, another relationship of Hoffman’s that proved useful. It’s a ridiculous role, but Downey finds subtlety in his performance. “He’s playing a vulnerable character who builds a fortress around himself,” Hoffman says. “Robert really tapped into that part of the character and found ways to express that vulnerability.”

A fast-talking and hyperliterate performer, Downey handles DeLillo’s idiosyncratic dialogue. When Schwimmer eventually confesses to Nicky that he also loves the Red Sox, Downey calibrates the comedy-to-sincerity ratio precisely, hitting the staccato beats in “I went to 50 or 60 games a year. All by myself. I was one of those kids with scabby elbows. I called out to the players. ‘Look over here. Hi, I’m Steven. My parents are divorced.’” Repeatedly, the film emphasizes the intensity of loving a team since childhood and how the sport becomes a key part of one’s history. “If you have a team you’ve followed all your life,” Nicky says, “and they raise your hopes and crush them, and lift them and crush them, do you want me to tell you what it’s like? It’s like feeling your childhood die over and over.” DeLillo gives us the magic and dread of American sports fandom.

“I’ve been declining interview requests for some time now. Nevertheless I’m glad to learn that the film is still being discussed and written about.” — Don DeLillo

Numerous DeLillo interviewers and critics have attempted to tackle how he writes speech, its terse poetry, an almost alien quality that can be comic and/or foreboding. (During a plane malfunction in White Noise, someone on the flight deck shouts over the intercom at the passengers, “We’re falling out the sky! We’re going down! We’re a silver gleaming death machine!”) “Well, there are fifty-two ways to write dialogue that’s faithful to the way people speak,” DeLillo told The Paris Review. “It is my theory that if you record dialogue as people actually speak it, it will seem stylized to the reader.” He then described the dialogue in his novel Players as “jumpy, edgy, a bit hostile, dialogue that’s almost obsessive about being funny whatever the circumstances. New York voices.” That’s how Game 6 sounds too.

In addition to producing, Dunne played a friend of Nicky’s in the film; he tells me that performing DeLillo “requires a real innate understanding—an understanding that can’t really be explained by a director—of what those short sentences mean and how they end. If you don’t hear them when you’re reading them on the page, you probably aren’t gonna get them. They’re like alarms or bursts.”

The first line spoken in Game 6 is, “This could be it.” The sun comes up over Manhattan, Nicky stands at the balcony of his place and says it to no one—could be commentary on his career, could be about his Red Sox. Could be that he’s quoting his own play, in which the line is critical. It’s the line that the play’s parasite-addled star can’t remember, even though when he says it he’s only echoing another character. Late in the movie, watching the final innings of the game in a bar overrun with Mets fans, Nicky says it twice. The legendary Bronx-born announcer Vin Scully, who is calling the game on TV, also says it: “With the Mets down to their last strike, this could be it.” Except that during the actual telecast he didn’t.

To rewrite history, Robinson convinced the veteran sportscaster to participate in this fiction, and Scully recorded DeLillo’s line via phone. A true fan, Robinson had produced the baseball drama For Love of the Game in 1999, which gave her an in to MLB and Scully. “I love producing movies because of these things you do that no one else will ever know about,” Robinson says. During a scene shot inside the Shea Stadium locker room there’s a chalkboard that reads “this could be it.” If it hadn’t been for Hoffman paying Shea directly for the access, they wouldn’t have got that moment at all. “That was the last day of shooting,” says Hoffman. “I think I spent an extra $20,000 out of my pocket.”

Robinson wrote the line on the chalkboard herself.

Game 6 premiered at the 2005 Sundance Film Festival. Citing the film’s “complexity and richness of speech,” Roger Ebert praised it; Dunne recalls sitting next to Ethan Hawke during the screening, who loved it too. (Character actor/producer Fisher Stevens, who sat on the other side, was merely ho-hum.)

At Sundance, the same skittishness that Universal demonstrated appeared to set in. Buyers were scarce. “We thought we would have more potential buyers,” Urdang says.

“We thought other things were going to happen that would have been better for the movie, and they didn’t happen,” says Robinson.

“At Sundance, you have this brief window where you’re the shiny object,” Hoffman says. “But in 24 hours everyone is on to the next thing.” (Setting a then-record for the festival’s biggest sale, Hustle & Flow made headlines that year when Paramount paid $9 million for the distribution rights.)

A new company, Kindred Media Group, run by Jeffrey D. Erb, made an offer. “They were completely in love with the film and promised to the moon and back in terms of how they were going to release it,” Urdang says. “We thought it was our best option. We made a mistake.”

“At Sundance, you have this brief window where you’re the shiny object. But in 24 hours everyone is on to the next thing.” — Michael Hoffman

Distribution is the monster at the end of the book that is making a movie. It’s capital intensive and requires a deep understanding of marketing. The distributor buys the rights and plans the advertising; they sell the movie to exhibitors and consumers. “A good deal is smarter than a good film,” distribution veteran Ray Price once said. “You can have the world’s best film, and nobody cares.” If you don’t secure distribution, no one will see your film. In 2005, for a highbrow indie like Game 6, this meant a theatrical release or bust. Urdang says that the streaming model of today would have been a better fit for the work Serenade produced in the early 2000s. (Serenade produced five films, the most financially successful being its last, a love story about living with Asperger’s called Adam, distributed by Fox Searchlight.) But at the time, the only route to success was to open in theaters, and hope for good press and word of mouth; otherwise, you’d go direct to DVD, where the schlock lived. “Our goal was always to release theatrically,” Urdang says. “What we realized was regardless of whether or not a film is made inexpensively, it doesn’t necessarily reduce the amount that has to be spent to theatrically release it. There’s still a high risk.”

A self-described “serial entrepreneur,” Erb has been involved with a number of movie-related companies. Kindred was his first, and Game 6 was the company’s first major theatrical release. He told me he first became involved in the movie business during a trip to Los Angeles in the early 2000s. “I was hanging out at Skybar at the Mondrian, shooting the shit with people at the pool,” he recalled. “I came home a few days later and the people I’d been talking with had Googled me and seen that I’d been involved from a financing perspective on a lot of different business opportunities. They asked if I’d be interested in helping to finance a production company.” That eventually led to the creation of Kindred.

The official Game 6 website launched in February 2006, a month before the film opened. The site’s press release is a rich document of Web 1.0 miscalculation. “Users of the site can submit the story of where they were on the night of Game 6 for a chance to win tickets for two to the premiere of the film and mingle with the stars at the after party.” The film’s tagline reads “WHERE WERE YOU ON THAT NIGHT.” Positioning the film as a sports flick is a peculiar way to sell a beautifully esoteric movie about anxiety, language, and failure. The release concludes with a quote from Erb: “There is such passion from baseball fans around that single night and that single game, that to be able to bring people’s stories to a wide audience is exciting.”

“The film was challenging,” says Erb. “People had a hard time classifying it. Sports people didn’t love it because it wasn’t a sports movie. And the independent people were confused about even going, because there was a sports tie. That was tough for us to overcome.”

“I remember how widely it didn’t open,” Dunne says. The film opened in New York and Boston—a move Erb says was intended to mirror the ’86 World Series—and expanded fitfully before leaving theaters. A platformed release, in which a film first opens in select cities and gradually expands, is a typical strategy for an indie, but according to Urdang, Kindred failed to fulfill its responsibilities: “[Kindred] never came through with any of their contractual requirements and obligations.”

Box Office Mojo reports that at its widest, Game 6 played in fewer than 15 theaters across the country. Erb questions the number, calling it “light,” and says that Kindred did its best to market the movie, citing newspaper advertising, a Manhattan premiere party, and promotions like the story sharing, in addition to signed T-shirts and posters. He concludes that “the film didn’t perform. At the end of the day, producers can be upset about that shit. But if people aren’t going to your movie, you can’t twist their arm. We expected it to take off, and it did really well in New York and bombed in Boston. From that point forward, it was about spending dollars on advertising, and there’s only so much you can spend if you’re not getting those dollars back. You gotta cut your losses. If they expected more than that, I think their expectations were unrealistic.” He added, “If something doesn’t take off, you’ve got people who might be bitter and like to point fingers. That’s how film people tend to work, because they don’t like to take responsibility.”

Erb says he stepped away from Kindred to focus on production rather than distribution in 2007. Per IMDb, he has produced 12 different film and TV releases, including a 2011 reality series about the cheerleaders of the Philadelphia Eagles, which he also directed—his first time behind the camera. In addition to ongoing work in film and TV, he currently works as the president of engagement at McCann Health, an ad agency in the health care sector.

“You think you’re fighting the key battle when you’re making the film,” Hoffman says. “You think it’s some version of D-Day. And then you realize, when you get to distribution, that it was a minor skirmish.”

Years after DeLillo wrote Libra, he summarized the mountains of evidence he sifted through to write the novel, the testimonies and odd ephemera of the federal government’s catalog of the Kennedy assassination, the photos of random litter in Dallas and Jack Ruby’s mother’s dental records, saying, “The trivia is exceptional.” A line from DeLillo that sounds like DeLillo dialogue.

And so, in 2014, a final coincidence: An Oscar contender from the jump, the story of a fried playwright dealing with a self-important critic and frayed relations with his daughter and ex-wife around the opening of his new work hit theaters—widely. It starred Michael Keaton and wasn’t called Game 6.

“I have never heard of this movie before.” —Alejandro González Iñárritu

Urdang says it felt like “déjà vu.” Robinson says she was “confused.” Hoffman acknowledges that the overlap between Game 6 and Birdman is striking but also says, “Sometimes you have similar ideas.” According to Urdang, the Game 6 team discussed it at the time and “you could either feel flattered or a little perturbed by it.”

“I don’t know if those writers read it many years ago and forgot that they read it,” Robinson says. At the 87th-annual Academy Awards, Birdman won Oscars for, among other things, Best Picture and Best Original Screenplay. When reached for comment about Game 6, Birdman director and cowriter Alejandro González Iñárritu said, via his publicist, “I have never heard of this movie before.”

In 1991, DeLillo told The New York Times Magazine that “I’ve always liked being relatively obscure. I feel that’s where I belong, that’s where my work belongs.” On a November evening in 2018, Urdang’s 35-millimeter print of Game 6 played at Metrograph, an independent cinema in New York’s Chinatown. DeLillo and his wife attended the screening, along with Robinson, Dunne, Urdang, and Hoffman. “I think Don felt very good about the movie,” Robinson says. It remains the only film written by the 83-year-old novelist. (An adaptation of DeLillo’s novel Cosmopolis was released in 2012, written for the screen by its director, David Cronenberg.)

“I’ve been declining interview requests for some time now,” DeLillo says. “Nevertheless I’m glad to learn that the film is still being discussed and written about.” (On June 24, Scribner announced the upcoming release of DeLillo’s latest novel. Entitled The Silence, it’s about a group of people watching the Super Bowl in a Manhattan apartment in the year 2022.)

Unless you order the DVD, it is currently impossible to legally watch Game 6. All rights for the film have reverted back to Serenade, and Robinson and Urdang have begun shopping it to streamers. But it isn’t so simple as, say, Amazon Prime writing the check and Game 6 showing up on your watchlist the following day. Because it was shot on film, Game 6 would need to be converted to a streamable HD format. There are still costs to be paid to see a movie made over a decade ago.

One night this spring Robinson was at home in New York City, watching Turner Classic Movies, when she caught an unusual and compelling film called The Silver Cord. An RKO release from 1933, it’s an adaptation of a stage play about a domineering mother browbeating her adult son into staying in the nest. For years, the psychosexual melodrama has been nearly impossible to see. Until it wasn’t. “One of the things about movies that’s pretty damn great is that they can reappear,” Robinson says. “A movie isn’t like a play, which has to live in your memory. Maybe you can go to Lincoln Center and see a bad version of the play on film, but that’s not the way you want to see it. A movie lives on.”

This could be it.

Ross Scarano is a writer and editor from Pittsburgh.