When the writer-producer-director Lucia Aniello thinks about her long relationship with The Baby-Sitters Club books, one thing that she remembers is the nausea. As a girl growing up in western Massachusetts, Aniello absolutely devoured Ann M. Martin’s landmark series, about a group of 13-year-old girls in southern Connecticut who form a neighborhood childcare collective. But her enthusiastic consumption was the problem: All that love had a way of making her physically ill.

“I remember, very explicitly, being in the back seat of a car and getting sick from reading—but just, like, putting my head out of the window to regain myself so that I could continue to read,” Aniello tells me by phone, a few days before this Friday’s premiere of the 10-episode Netflix program The Baby-Sitters Club, based on Martin’s novels, which Aniello executive produced and directed. “Like, I would push my body to the limit for The Baby-Sitters Club!”

As someone whose own mom was driven to purchase a set of purportedly anti-motion-sickness wristbands, probably from a Sharper Image catalog, so that all my back seat reading (and, OK, Game Boy playing) didn’t cause us to have to pull over, I completely understand. It feels odd, yet it is so utterly ordinary, to realize that one’s most personal memories are actually pretty widespread. All those vivid mental images I have of sitting on bookstore and library floors across central New Jersey, paging through Martin’s work? I was one of millions doing the same. All those times I spent copying the various babysitters’ chapter-opening handwriting styles, or daydreaming about the details of their lives—Kristy’s many brothers! Claudia’s high-ponytail cool vibes!—I thought I was inhaling the books in solitude, but I was never alone.

It was 1986 when Martin published Kristy’s Great Idea, the first book in what was originally ordered as a four-novel series. Since then, it has evolved into a cultural touchstone spanning 213 installments, some written by Martin and others by ghostwriters, as well as dozens of additional specials and spinoffs and, most recently, popular graphic novels. (There was also one season of an HBO TV show in 1990 and a movie in 1995, neither of which left too much of a lasting impression, although the show’s theme song was a banger.) An estimated 176 million copies of The Baby-Sitters Club have been printed over the years, and some of those sales have been relatively recent: Mark Feuerstein, who on the Netflix series plays the soon-to-be-stepdad to one of the lead characters, Kristy Thomas, tells me that The Baby-Sitters Club had been his young daughter’s favorite books even before he ever learned about the role. “My daughter actually organized her own babysitters club with her friend Eleanor,” he says, estimating that they were about 8 years old at the time, which might give you an idea of how robust the business wound up being.

But a whole lot of BSC readers are of a certain other age. Martin was in her early 30s when she first began writing the novels, and these days her early, passionate audience is even older than that. (Natalie Portman was 38 last October when she posted a breathless Instagram about a BSC book Martin had signed.) “The timing of this series,” Martin said in a Netflix Q&A, “was really a decision made by the fans—the original readers of the books who are now in their 30s and 40s. Many of them have become writers, editors, producers. There was just so much renewed interest in the books from these adults who had read them when they were kids.” This included Aniello, as well as Rachel Shukert, the Glow writer and longtime BSC fanatic who is an executive producer and the showrunner of The Baby-Sitters Club.

In putting together a much-anticipated reboot of The Baby-Sitters Club, the creative forces behind the series drew upon their very specific memories of place and time, reaching way back into that wooziness of the back seat while still driving forward. What distinguishes the Netflix series is the way in which the show stays true to its increasingly long-ago source material while still rooting itself firmly in the present, using nostalgia as a foundation rather than a roof. The Baby-Sitters Club books may be of my generation, but its latest iteration feels designed to speak for, and to, a new wave of fans.

The Baby-Sitters Club remake I first envisioned, when I heard that the women behind Comedy Central’s bawdy Broad City (Aniello) and Netflix’s glam-gritty Glow (Shukert) were involved, is not The Baby-Sitters Club remake that actually exists. Netflix’s new series does not seek to subvert the tenets of the original novels, nor is it trying to leave them in the dust in some showy attempt to spin its wheels forward. We aren’t glimpsing Claudia or Stacey 30 years hence on a Condé Nast elevator; we also aren’t getting, say, a try-hard bottle-episode concept in which we see the world only through the eyes of a baby for 30 minutes. Instead, the series plays things admirably straight, a model of clear-eyed fidelity to the original text, while incorporating just enough humor and modern references to make the show feel current and new. The resulting vibe can be gleaned from the headlines of a number of recent reviews:

Vanity Fair declared “Netflix’s Baby-Sitters Club Series Is Near-Perfect Kids’ Television.” Entertainment Weekly summarized it as “Feel-Good Fun.” IndieWire called the show “A Perfectly Pure Distillation of Ann M. Martin’s Book Series.” Vulture deemed it “A Welcome Surprise and Utter Delight.” And The New York Times just made me hungry with its take: “chewily wholesome—this is an oatmeal-raisin cookie of a show.”

That last one is particularly apt, because Aniello says that when she first started shooting the series, in 2017, she was in the midst of watching “10 thousand hours of The Great British Baking Show,” she says. “I needed something, I was craving something, that felt comforting, that felt like, you know, there are good people, there is hope to be had.” Aniello couldn’t swing a Kid Kit around Los Angeles without hitting someone for whom The Baby-Sitters Club felt foundational, but when she met Shukert she knew she had found a real kindred soul. Both women had spent years reading the books and shared a reverence for their original spirit. And Aniello admired Shukert’s other work: “Glow was very appealing to me,” she says, “because I thought it was such a great balance of comedy and humor. And also real characters fumbling and coming of age.”

Aniello and Shukert teamed up with producer Lucy Kitada, as well as Naia Cucukov of Walden Media, the company who owned the Baby-Sitters Club rights. “The four of us just pitched it around town,” Aniello says, “and it really just kind of felt almost like we were a little Baby-Sitters Club, you know?” They regarded The Baby-Sitters Club less as something to twist or turn for their own purposes and more as something to steward for a new generation of viewers. “There’s something about even the most basic message of these books that feels really of-the-moment,” Aniello says, even if some of them were written 30 years ago. “And I think we just didn’t want to pervert that too much.” Instead, they made adjustments to modernize the story in small but meaningful ways.

Set in suburban Connecticut, the original Baby-Sitters Club books introduced a group of girls with such distinct and disparate personalities that readers couldn’t help but pick one or two to define themselves by. (My generation loves to do this; we have related to both Samantha Parkington and Samantha Jones over the years.) Still, the fictional town of Stoneybrook was not exactly a melting pot of diversity. Martin’s work does include a few noteworthy exceptions, like Claudia, who is Japanese American, and Jessie, who is Black, but the majority of her characters were white women, most of them well-off. The Netflix series makes broader representation a priority. Both Mary Anne and Dawn are portrayed by actresses of color. Dawn’s father is a gay man. Mary Anne babysits—and emerges as an ally—for a transgender child.

The TV series also moves beyond its source material when it comes to grappling with the issues that teens and their families often face. Martin’s work memorably portrayed a spectrum of challenges and lives—I first learned about autism from the books, which also featured characters who were managing diabetes, navigating divorce, and grieving—and the TV adaptation adds others that feel relevant today. Stacey (sans her perm from the books) tries to hide a humiliating viral video from her past. Dawn teaches Claudia the phrase “socioeconomic stratification.” The leader of a rival babysitting club smarmily and disingenuously tries to tell the girls that they shouldn’t be dragging other women down. All of these tweaks feel vital and earned, pulling on the source material’s best threads.

Not all of the updates are such serious business; some are just fun reminders of how long it’s been since the books were released. In the TV show, when the girls decide they want a landline phone for their club, they order one on Etsy. When it arrives, they behold it as if it were an ancient relic, because it is. “Iconic,” Claudia whispers with approval, as a new gray hair sparkles, far less aesthetically, on this viewer’s scalp.

Back in the day, my own iconic landline used to ring quite a bit, if I do say so myself. I was probably about, oh, 10 years old the first time I booked a for-real non-family gig in which I was well and truly in charge of a small child, a toddler named Wren with whom I had played spontaneous peekaboo at a local playground with enough enthusiasm that her mom finally asked for my number. In the decade that followed, in dozens of homes up and down the tri-state area, I did it all: changed diapers; successfully put four kids to bed (how?!); lugged towels and slurped ice cream on someone else’s family vacation; fed pets; and fed Wren and Griffin and Miles and Spencer and “Z” and Emma and Elliott and Hannah and Other Hannah and Other-Other Hannah, the One With the Lizard.

I did dishes and ate Cheetos and fiddled with remote controls and left behind extremely involved scavenger hunts for the kids to tackle when they woke up. I nodded responsibly as perfumed mothers with freshly applied, bordering-on-severe lipstick (Nars brand, I’d later learn when I snooped) pointed their manicured fingers at handwritten lists of phone numbers to dial in the event of emergency (a restaurant 35 minutes away, a hospital, “Steve’s car phone”). I chirped “No problem!” when those same mothers, their voices now louder and huskier, rang the house phone (which I answered?!) many hours later to say they might be back a little bit late. I was driven home, I now realize in hindsight, by people who absolutely were drunk. I remember that I frequently fumbled to get out of the car when we got to my driveway, because every car’s passenger door mechanism was just different enough to make you think. If reading The Baby-Sitters Club books helped me see the world through various perspectives, actual babysitting was like having an internship at Humanity, Inc.

Having absorbed so much, there was nothing more horrifying, years later, than to hear myself as I gave instructions to a babysitter under my own employ, probably with lipstick all over my teeth. To have young children is to constantly be looking back and forth between your past and their future, as if you’re crossing a road together, because you are. It is to realize that your strongest, strangest memories from childhood, like playing with a bunch of anthropomorphized chicken nugget Happy Meal toys from McDonald’s, are pretty much the same ones that your kids are forming right this very second as they sit there fondling some piece of branded plastic garbage that came with a bag of fries. Adding a babysitter to the mix puts another twist into this dynamic: Do these friendly, capable adolescents look at me the same way I used to perceive the mothers for whom I worked? Are they the same as I was then? Am I?

“You have my cell number,” I used to say again and again to the promising, smooth, capable faces of the babysitters standing before me in my own home while my sons stared up at them from behind my knees. Overhearing myself and how unchill I sounded would make me perspire right there in my dumb “date night” outfit. Who knew I’d someday pine for that particular brand of flop sweat? I haven’t experienced it in many months, ever since the Earth fell off its axis and the babysitting stopped and I started spending every minute with my own kids, for whom I have yet to ever put together a scavenger hunt.

The other day, feeling guilty, I had a great idea: I’d order a tie-dye kit, and ensure hours of backyard fun and high fashion! When I went online to buy one, though, they were almost entirely out of stock everywhere I looked. In this way, being a parent has a lot in common with being a reader of something like The Baby-Sitters Club, and not just because both things involve significant amounts of carsickness. You may believe your experiences and memories and ideas are yours and yours alone, but you’re actually part of something much bigger than yourself.

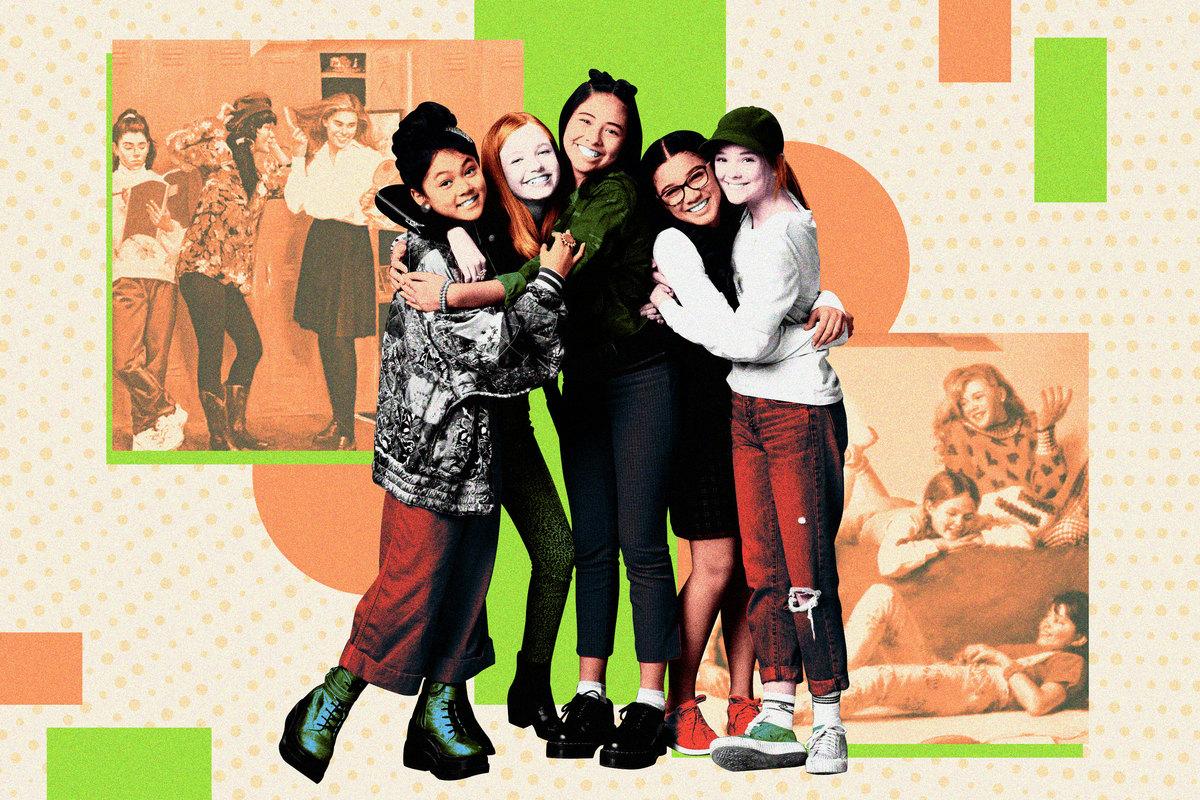

“Thirteen-year-old girls are exactly how I remember,” says Aniello. “They’re funny and they’re goofy and they’re weird and they say really, really ridiculous stuff.” The young actresses in the series are a marvel; ever since I finished the series I’ve found myself genuinely missing their characters and idly wondering what they were up to. Tiny Sophia Reid-Gantzert’s weirdo, quasi-goth take on Kristy’s little step-sister Karen, a character who had a 122-book spinoff series of her own, was probably my favorite performance, but to mention any one actress is to feel panicked about slighting the wonderful rest. Still, here’s another compliment worth boosting: Feuerstein, who shared a number of scenes with Kristy, played by Sophie Grace, compared the actress to a young Sandra Bullock. (And he would know, having worked with the latter actress: “I played her husband who gets hit by a truck in Practical Magic,” he says.)

Netflix has yet to announce any follow-up seasons to this one, but with so many strong core characters, as well as so much opportunity to build out the universe of families for whom the girls babysit, the series seems well-positioned for the future. If anything, the biggest wrinkle might just be time: It’s hard to know when it will be safe for anyone to return to production, and teenagers have a way of growing up fast. As she directed a cast full of teens, Aniello found it hard to remember that she is no longer one of them. “When I’m hanging out with them, I’m like, yeah, in my mind I’m 13 too!” she says. “Now they don’t see me like that at all.”

Once again, her words resonate with me; recently a tweet made the rounds that cut me deep. “i’m awake at 3 am,” began the post, which would ultimately be retweeted nearly 78 thousand times, “and i just want everyone to know what gen z says about millennials on tiktok…..” As I scrolled through the accompanying remarks of young people roasting my generation, I felt mostly relief: Never had I ever uttered the words “adulting” or “doggo,” and I also didn’t have anything in my Twitter bio about Harry Potter. Maybe as an Elder Millennial, none of this stuff applied to me. Maybe I was the Switzerland of microgenerational squabbling, dignified and disinterested.

But then I got to the final screen shot. “All they do is drink wine, post cringey ‘90s kid’ meme, talk about tech start-up and lie,” wrote one user. Well, shit, busted. “we get it, your a 90s kid <3” followed up another commenter, and when I read that I wished I could just grab all my go-to Knicks and Nickelodeon references and slink into the bushes like Homer Simpson does in that one Simpsons episode from … oh dear… 1994.

The best thing The Baby-Sitters Club series does is to direct its focus through the wide-eyed gazes of the teen babysitters it revolves around rather than through the more wild-eyed lens of the harried parents who forget that the world doesn’t revolve around us. That’s not to say that the show ignores the “adult cadre,” as Feuerstein terms it. Quite the opposite: Among the grown-up characters, there is divorce, and flirtation, and the ramifications of the aforementioned “socioeconomic stratification,” and grief, and unpleasant dentist appointments, and more divorce, and more flirtation (at one point involving a gifted turtle). And most conspicuously, there is Alicia freaking Silverstone, as iconically retro as any landline telephone.

Once upon a time, in 1995, a then-teenaged Silverstone played the titular babysitter in a movie called The Babysitter. A quarter-century later, at age 43, she now plays a mother of four children in The Baby-Sitters Club, a meta wink to The Baby-Sitters Club’s cohort of ’90s readers who also grew up seeing her in Aerosmith videos and in the more timeless Clueless. (For Aniello, Silverstone’s most memorable role of old was in Excess Baggage; for me, it’s the “Amazing” video and that one news cycle about how she pre-chewed food for her baby, Bear, like a bird.) “The girls were so cute with Alicia,” Feuerstein, who plays Silverstone’s beau, says about the young actresses. “They all worshiped her from Clueless. They were not shy about how much they were obsessed with her and her character.” It’s genuinely comforting to know that I have this, at least, in common with today’s teens.

“I really feel like the next generation is going to save the world,” says Feuerstein, who has three kids of his own, “as opposed to ours, who helped ruin it.” He’s joking, mostly, but The Baby-Sitters Club really did leave me feeling an optimism I hadn’t been acquainted with in quite some time. Everyone involved in the series seems to care, whether it’s Shukert and Aniello putting it all together, or the characters themselves, who totally bicker but also consistently support one another and do the right thing. When I saw a tweet the other day seeking soothing recommendations for a TV show in which the characters actually “make good choices,” I initially had trouble thinking of one; good choices don’t often make for good TV.

Unless it’s The Baby-Sitters Club, I remembered, which thrives on kindness and consideration, just like Ann M. Martin’s original series always did. But don’t worry: While the show may traffic in high concepts like community and decency and inclusivity, it still knows when to go quickly and cleverly low. In one of the final episodes, when two characters run into one another at a summer camp, one of them makes a comment about how it must be a cosmic sign that they wound up at the same place. “Or it just means that our moms got the same Facebook ads,” says the other, and I laughed and I winced all at once. Even though I knew it wasn’t, the line felt personal, like it was written about and for me and only me. It’s the exact same way the books always made me feel.

An earlier version of this piece incorrectly stated that Glow is streamed on Hulu; it appears on Netflix.