Phoebe Bridgers was supposed to be in an arena right now.

If the year had gone according to plan, she’d be calling from a green room somewhere in America. The original idea was that she’d open for the National in Australia and New Zealand in the spring, and then she’d spend the summer opening for the 1975 for an extensive tour that would have included dates at Madison Square Garden and Red Rocks Amphitheatre. Phoebe Bridgers’s songs are like when your funniest friend suddenly drops her guard to let you all the way in, revealing an untamed world that her sarcastic burns could never quite obscure. These poignant, wry observations have already earned Bridgers a dedicated fan base, but this exposure could have increased that following substantially.

But thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic and the corresponding worldwide shutdown, her summer plans have changed dramatically, and now involve 100 percent fewer arenas. In your own way, maybe you can relate.

So instead, she’s stuck inside her apartment, talking while walking on her treadmill on a Friday afternoon in early May. When life was (not really in the big picture but at least in comparison, you have to admit) sane in the Before Times, she would walk around her neighborhood while doing phoners. She doesn’t feel like going outside anymore.

“Yesterday was my first trip to the store in three weeks, and everybody is just fucking out. Dude, it’s so scary,” she says. “I don’t like going on walks because it sends me into a spiral about what the world looks like, shuttering businesses and people without masks. I’m just too scared.”

This is a change, as slowing down doesn’t come naturally to her. Since releasing her debut album Stranger in the Alps in 2017, Bridgers has become a ubiquitous presence in the lives of indie rock fans, a household name in houses with a well-curated vinyl section and a few framed gig posters on the wall.

She’s always around, always welcome, and seemingly always collaborating with someone. She formed the supergroup Boygenius with her friends and fellow astute-beyond-their years 20-something songwriters Julien Baker and Lucy Dacus, releasing a harmony-rich EP in 2018. For good measure, she followed it up with another supergroup, teaming up with Bright Eyes’ Conor Oberst for Better Oblivion Community Center, which released a spiky self-titled debut album in 2019. She’s also filled her collaborations punch card by working with the National’s Matt Berninger, Hayley Williams, the 1975, Lord Huron, and even Fiona Apple. And if that’s not enough Bridgers content in your life, she maintains one of the funniest and filthiest artist accounts on Twitter.

Her ascendence from unknown to mainstay “seems totally gradual” to her. “There’s a Bright Eyes tour manager who used to riff that Bright Eyes was the best new band 15 years running. And I kinda feel like that. As I reach new people, I’m new to them,” she says. “But that being said, I also think that the first good music that I released was my first record.”

Bridgers, 25, lives alone and wanted to foster a dog. But apparently, everyone in Los Angeles beat her to it: “I think they’re being kind of swept up.” So instead, she’s been trying to find other ways to stay busy. “I’ll probably clean my house again,” she says. “I feel like we’re all figuring out how much a house needs to be cleaned.” She has also started rereading the speculative fiction novel Oryx and Crake by Margaret Atwood. “She fucking predicted deep fake, she predicted COVID-19,” she says. “It’s fun to reread something that has way more relevance now.”

Then there’s the matter of figuring out how to promote her second album, Punisher, which a few months ago could have been accurately if a bit hackily described as “feverishly anticipated” by critics. When plans to shoot a video in Japan for her single “Kyoto” fell through, she made a green-screen video and later performed the single for Jimmy Kimmel Live! from her bathroom. In lieu of taking Punisher to her fans on the road, she’s taken them to the loo and elsewhere as part of her “Phoebe Bridgers Virtual World Tour” of streamed concerts from throughout her apartment, including two from her bedroom.

She thought about delaying Punisher, “but in the back of my mind I was like, ‘This is not a short thing. If I delayed it, then when would we put it out?’ It seems like the news gets worse every day. … We even had to move vinyl pressing plants ’cause the one we initially were going to use fucking shut down forever,” she says. “For my mental stability, too, it’s like, ‘What, we wait till the end of the year?’”

It won’t be surprising at all if one day we get a great song from Bridgers about the disorienting feeling of life in our current moment, but for now there’s plenty of disorienting feelings to be found on Punisher, which she began working on as soon as Alps was finished, and for which she again worked with producers Tony Berg and Ethan Gruska, this time adding Bright Eyes’ Mike Mogis into the mix. “The guiding theme was ‘God, I need a second album’ and mostly just feeling stressed,” she says.

Bridgers excels at writing about feelings that you don’t necessarily want, or know what to do with, or that don’t even have a name but stubbornly continue to exist. On “Funeral,” one of the standout songs from Alps, she writes about performing at the service of a friend who died of an overdose. After then musing about a sadness that she can’t seem to escape, she snaps back into focus. “Wishing I was someone else, feeling sorry for myself / When I remembered someone’s kid is dead,” perfectly nailing the strange feeling of feeling bad about feeling the wrong thing at the wrong time.

On Punisher, she continues to observe how profound moments of realization tend to come amid day-to-day routines and the aimless sprawl of life, digging deeper into the small moments of life while pushing her arrangements in striking directions. On the spritely new-wave chamber pop “Kyoto,” a trip to the arcade and a 7-Eleven during a day off on tour gives her just enough time to wonder why she has the right to be on tour at all, while a quiet night out on the devastating space-folk ballad “Chinese Satellite” becomes a meditation on how we become engulfed “in the idea of routine, and how if you don’t mix up your environment very often, the days blur together like they are now,” she says, adding she often doesn’t understand her songs until long after they’re done. “It feels like I’m just making shit up and talking about someone else almost,” she says. “I have the feeling every time I finish something. ‘That was the last song. It felt good. Now never again.’”

Bridgers grew up in Pasadena, California, and was always adjacent to the entertainment industry. Her dad was a carpenter who built sets for film and television, and her mother, Jamie, had a variety of white-collar jobs, from receptionist to house manager for a fine arts complex. (Jamie is currently a stand-up comedian. “She has made jokes about me being a musician, and STDs and stuff. She’s pretty raunchy. It’s great.”)

“This whole COVID situation is reminding me a lot of high school, actually. I’m in bed all day. I eat whatever I want. A lot of the time I don’t have energy to reheat something, so I either go back to sleep or make a toaster waffle,” she says. “I feel like it’s weirdly like exposure therapy to my depressed teen years.”

I have the feeling every time I finish something. ‘That was the last song. It felt good. Now never again.’Phoebe Bridgers

Her parents divorced when she was 19, and in interviews she has alluded to her father’s substance misuse issues (or as she said in GQ, his “drug thing”) and says they have a strained relationship. But she also credits him for filling their house with music, including plenty of Jackson Browne and Joni Mitchell, when she was a child. Later she would also gravitate to the brooding of future collaborators and friends like Oberst and the National. She’s always known she wanted to be a songwriter. “Before I knew how to do it. Before I was making anything good, I wanted it.”

She attended the Los Angeles County High School for the Arts, and gives the experience a mixed review. “The best thing about that high school was just the amount of practice I got. I don’t know how much I learned about songwriting other than just life experience, but I sang every fucking day and took Music Theory class,” she says. “I think it was cool being surrounded by people who also knew exactly what they wanted to do with their lives.”

After high school, and her high school punk band Sloppy Jane (which appeared in a few Apple commercials after catching the eye of a talent scout) ran its course, she began gigging around and demoing. Her friend and former music industry lawyer John Strohm remembers hearing about her from Andy Olyphant, “a career A&R guy” who used to work for Atlantic Records and reached out to him for help with a publishing deal he was pursuing with Bridgers that never came to fruition.

Strohm used to play in the Boston indie-rock trio the Blake Babies, alongside Juliana Hatfield and future author Freda Love Smith. The band dissolved after Hatfield began a solo career, and after a stint playing in the Lemonheads, Strohm began rethinking his music career. “I kind of hit a crash and burn point I was like, ‘I don’t know what I’m doing. Maybe I’ll go to law school.’ It was probably a more self-protective and pragmatic choice than becoming a heroin addict.”

After a stint as “a regular corporate lawyer,” he began working as “sort of entrepreneurial artist lawyer, where my business model was to try to find great artists and really start to help them in their careers before they could really afford to pay me,” he says. “So that when they got the wheels on and they were professional career artists, then they would be able to afford my services, which sounds kind of like a wonky business plan, but it worked.”

He retired his law practice after he was hired to be president of the storied folk label Rounder Records in 2017. Before that, he worked with Alabama Shakes, Waxahatchee, and Bon Iver. He knew he wanted to work with Bridgers as soon as he heard her demo for “Georgia” (“it blew me away”) in 2015. “Based on her magnetic personality, the strength of her songwriting, her incredible voice, and ultimately, her ambition to do it, that she was somebody that was going to have a career,” he remembers. “There was no way that she could not.”

When Strohm first got to know Bridgers, he would spend time with her, Berg, Gruska, and her drummer and former boyfriend Marshall Vore, and also invited her on the road to open for a few Blake Babies shows.

“When we were traveling with Phoebe, we weren’t listening to music, we were just talking to her and she was just keeping the conversation going in a very engaging way,” he says. “One thing that always astounded me about her and a handful of other artists like her is that she’s literally easily young enough to be my daughter. I’m 53 years old. She’s about 30 years younger than me, so there’s a giant age difference there. And in some ways, you feel that age difference. But I feel like with certain kinds of musicians who come up in a certain tradition of music-making, and collaboration, and touring, stuff like that, that even though there’s this giant age difference, we have way more in common than we did that differentiated us.”

Strohm would tell his followers on Facebook to show up early for the opener and would post videos of her performances to his page. One performance, recorded for Birmingham Mountain Radio on the show Reg’s Coffeehouse, caught the eye of Chris Swanson, cofounder of the independent record label Dead Oceans. Eventually, Strohm would negotiate her deal with the label Dead Oceans as well as her publishing deal. “When I first started working with her, I was like, ‘Man, she’s got everything. I just wish she was more prolific. Because there was a period of many months when she didn’t write any new songs,” he remembers. “It’s like, ‘When is she gonna finish this album?’ Because it really just felt like if she could just get to the finish line ...,” he says, trailing off before catching himself. “But now we understand why she was blocked.”

While gigging around L.A., Bridgers caught the attention of Ryan Adams, who released her single “Killer” through his label PAX AM in 2015. As revealed last year in an article in The New York Times by Joe Coscarelli and Melena Ryzik, they began a romantic relationship when she was 20 and he was more than twice her age. The article recounted how, she says, Adams became emotionally abusive, and after she ended the relationship “Adams became evasive about releasing the music they had recorded together and rescinded the offer to open his upcoming concerts.” (Through a lawyer, Adams contested the accounts of Bridgers and many other women.)

Serious artists who are gonna make a difference culturally and are gonna be the kind of cultural pivot point that Phoebe is should be taken seriously.John Strohm

A year later, she reflects on how her life has changed since the article’s publication. “I guess I just get to talk about that shit a little bit more than I did before, and I met tons of great people through it. It was definitely worse right before it came out. I was afraid it wasn’t gonna come out, afraid we’re gonna get sued. You still gaslight yourself and it’s like, ‘Did any of this shit happen?’” she says. “And then the day it came out, no matter how many people told me to go fuck off and die on the internet, I met so many amazing people and got so many fucking emails that made me really emotional, being like, ‘I was the barista down the street from the studio,’ or whatever. It just made me feel good.”

Strohm knew “some of the ugly stuff around the Ryan Adams relationship, but not the whole thing.” But he remembers the creative block she was in afterward.

“She was having a hard time writing because she was struggling with that stuff. At some point, she just really found her voice and started writing songs,” he says, adding that her becoming friends with Oberst, who would guest on Alps, “had a lot to do with it. And I know that ‘Motion Sickness’ was one of the songs that came later, and where she’s able to really talk about that. And then very quickly after a certain point, she was able to finish the record.”

With respect to Pusha T, “Motion Sickness” was the most devastating musician-against-musician dis song of the ’10s, with Bridgers owning up to her own conflicted feelings about hating and also missing Adams, and then torching him at the end by using one of his own lyrics against him: “You said when you met me, you were bored / And you, you were in a band when I was born.” The single was the first time most of us heard Bridgers, and it immediately made it clear this was an artist who wouldn’t be taking any more shit from anyone.

“Look, I mean I came up in a band that was me and two women, and I saw the worst shit from day one. And it was in some ways it was worse back in the ’80s and early ’90s for women in the industry, but in some ways, it’s just the same shit,” Strohm reflects. “And I’m so glad that we’re in a period where we’re actually talking openly about it and not just sweeping it under the rug, because it infuriates me. Because serious artists who are gonna make a difference culturally and are gonna be the kind of cultural pivot point that Phoebe is should be taken seriously. And people who work with artists and work in music should take artists seriously.”

Alps was released right as the #MeToo movement began kicking into high gear after the exposé of Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein’s numerous incidents of sexual assault and harassment. While doing interviews for Boygenius, Bridgers would comment that sometimes after she would shoot down condescending “women in music”–style questions from male journalists, she could tell a bunch of other questions were being deleted. “I don’t know if it’s better. I mean I think that more places are afraid to send an old white man to go interview a young woman,” she says. “Hopefully, people are just hiring more women, and even if it’s just because they have to or for a look, they’re editing out the questions that they have seen other people get ripped apart for asking. So it seems like everybody’s on their toes a little bit, and the people who should be on their toes are on their toes.”

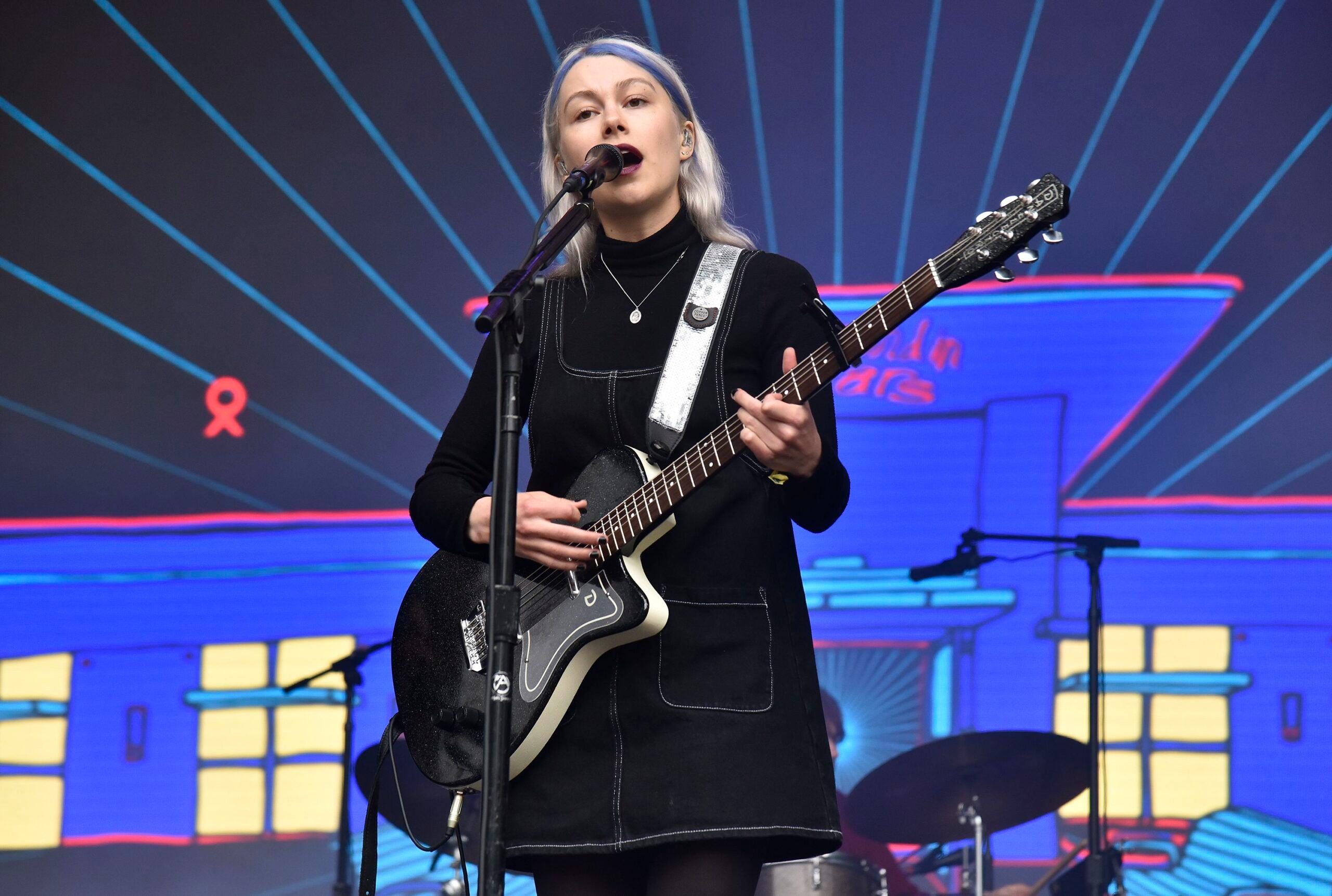

One of the quirks of the Phoebe Bridgers Cultural Experience is that she is a goth who doesn’t make gothic music. Though she dyes her hair frequently, her default tends to be stark white, and her clothing is always black. Her music might not be indebted to the Cure (covering “Friday I’m In Love” doesn’t really count) or Bauhaus, but the darkness is strong with her nonetheless.

“My best friend in high school had shaved eyebrows and was super, super goth and drew on her eyebrows with eyeliner every day. And I’ve always kinda wanted to be goth, but I had a lot of secondhand clothes and not a ton of money, so I had a very weird high school aesthetic,” she says. “And then when I graduated and started making money, I was like, ‘I’m only buying black clothes from now on. Plus the occasional wedding dress.” (She owns several, apparently. She hopes to wear them onstage once she can tour again. Whenever that is.)

The visual motif for Alps and the singles that came from it were children in ghost costumes, while the cover art and attendant videos for Punisher feature her in skeleton pajamas, which continue to get a lot of use.

“I put on the skeleton suit, and it’s like, ‘Damn, this is comfortable.’ So I think being a character is funny but it also, it is rooted in reality. Like I really have been wearing the same pajamas for like two months. I wash them every three days, and tried to get another pair online, but they’re sold out.”

She’s goth on the outside but a classic rocker at heart, gravitating toward the sort of direct songwriting that’s existed for more than 50 years and can’t really be improved upon but that can be twisted into a singularly resonant vision. She’s sung of mourning Motörhead’s Lemmy Kilmister and about arguing about John Lennon; and on “Graceland Too,” she paints a scene of a hopeless dreamer in love with the promise of music’s ability to change your life, even stealing the line “rebel without a clue” that Tom Petty may have stolen from the Replacements’ Paul Westerberg.

But there’s one legend who looms especially large for Bridgers. The title track of Punisher is her imagined conversation with the late Elliott Smith, whom she notes once lived in a bungalow near her. She didn’t discover his music until five years after his 2003 suicide. “I wish I could’ve heard it without that, first.”

To Bridgers (and plenty of other musicians) a “punisher” is slang for “someone who doesn’t know when to stop talking. It’s a specific reference to when fans don’t know when to shut the fuck up, which I know I have definitely done and it has been done to me. One time a guy came up to me after my set and he was like, ‘Hey can I give you some advice?’ It’s just people who don’t know that they’re torturing you. So in this context, I’m doing that to Elliot Smith in the song. The idea would be that he’s trying to escape from me and I’m following him home or something. It’s like weird, fucked-up fan fiction.” (Though Smith had a reputation as a mercurial, troubled person, she insists that from what she’s heard “he was exceedingly sweet to fans.”)

So depending on your pop culture or political leanings, you’ll either be relieved or disappointed that the album title isn’t named in honor of the Marvel comics gun-toting antihero, who in recent years (to say nothing of recent weeks) has become a right-wing symbol of “law and order,” much to the chagrin of many Marvel employees. She was unaware of this association, and not happy to learn of it. Or in her words: “Oh, great.”

If Smith were still alive, the world would be a better place for innumerable reasons. One of which is that there’s a very good chance that he would have collaborated with Bridgers. Everyone else seemingly has. Working with people you’ve loved since you were a teenager sounds like it would be nerve-racking to civilians, but she insists that they all just make it so easy.

“I’ve yet to feel intimidated by someone. Maybe I was a little bit intimidated by Fiona Apple, but that’s just because of how much I worship her,” she says. “But Matt is an enormous goofball and so is Conor. Nobody talks to you like, ‘Oh my God, I’m talking to such a huge fan right now.’ They all talk to me like I’m their fucking peer, which is so wild.”

Strohm doesn’t think it’s so wild. If anything, he understands why the indie heroes of her youth would gravitate toward her.

“Why do any of us do what we do? It’s because we love music. People get so excited about Phoebe for the same reason I got so excited about Phoebe, because what she does is just immediate and undeniable,” he says, adding that none of the artists who reached out to her “are opportunists who are looking to get a feature with the latest and greatest to elevate themselves. They’re just fans of what she does and want to be part of it. … I know it’s incredibly affirming and satisfying for her to have the opportunity to work with these artists who she loves and admires. And for them, it’s just like, ‘Man, there’s nothing cooler than getting to collaborate with somebody who’s really good, and really exciting, and really is just at the beginning of something extraordinary.’ Because I think that Phoebe is like a Joni Mitchell for our age. She’s that good.

“But I’m sure if I were to say something directly to Phoebe like, ‘Oh, you’re like a Joni Mitchell for our generation,’ she would be very embarrassed and probably annoyed with me for saying that.”

There’s plenty of people left on her dream collaborations list, including the ambient artist Grouper, songwriter Julianna Barwick, and the composer Nils Frahm. “My life is curated exactly to make me happy, so I’m not trying to expand my collaborations until it pops up naturally. I rarely meet people I don’t give a shit about who are famous,” she says, chuckling. “You know what I mean? I tend to meet people that I really worship.”

But as curated as her life is, like everyone else, it’s on pause at the moment, so dream collaborations will have to wait. Since no one can live on Margaret Atwood, cleaning, and promotional duties alone, she’s also been passing the time in the most characteristic way possible: true, intimate connection with other people, which can be just as satisfying one-on-one as it is in an arena.

“I end up on the phone a lot more. I feel like people are finally answering the question, ‘How are you?’ in a real way, which is nice. I talk to people I haven’t talked to in years and I’m like, ‘How are you?’ And they’re like, ‘Man, you know ... been going to therapy more.’ I feel like I’m having a lot more honest conversations. So I go through phases, but right now, it’s not so hard.”

Michael Tedder has written for Esquire, Stereogum, The Village Voice, and Playboy, and is the founder of the podcast and reading series Words and Guitars.