At one point in The Last of Us Part II—to tell you when would be a spoiler—a character I controlled briefly disobeyed me. No matter which way I moved my joysticks, Ellie—a beloved but mostly computer-controlled companion in The Last of Us, elevated to a primary, playable role in both the downloadable prequel to Naughty Dog’s 2013 touchstone and in the newly released sequel—refused to look at herself in a certain mirror. In an earlier, light-hearted scene, I had maneuvered her into the same spot, and she had obligingly looked dead ahead and made funny faces. But now, when I tried to force her to face forward, she obstinately looked left or right, as if unwilling to meet her own gaze.

Considering Ellie’s actions up to that point, it made sense that the sight of herself might make her ashamed. I’m not sure whether that apparent revulsion was a conscious design decision or a serendipitous quirk in the code; when I tried pointing her toward a different mirror, she grudgingly complied. It’s a testament to Naughty Dog’s often-understated storytelling and uncanny animation that this act of rebellion conceivably could have been intentional. It’s fitting, though, that when I looked in the mirror, I saw only Ellie’s face reflected. The Last of Us Part II is among its medium’s most painstaking portrayals of suffering, a game that convincingly simulates the experience of scraping by in a broken, cruel world. What it doesn’t ever do is implicate the player in its protagonists’ transgressions. If I were Ellie, I wouldn’t want to look in the mirror either. But even before I failed to make her confront her reflection, I never felt fully in control. I followed Ellie’s lead reluctantly, killing under duress. Naughty Dog made me do it.

In The Last of Us, released first for the PlayStation 3 and in remastered form for the PS4, the player takes control of Joel, a self-interested smuggler who’s not above the bloodletting that it takes to thrive in the post-apocalyptic America of 2033. Shortly after the game begins, he meets Ellie, a teenage girl who’s immune to the fungal infection that has turned most of the population into mindless and murderous hosts. Her immunity makes her precious to the Fireflies, a revolutionary militia that’s trying to restore civilization and develop a vaccine. The group tasks Joel with transporting her to a Firefly hideout beyond the border of the strictly controlled Boston quarantine zone, but when he and Ellie get there, they find the Fireflies dead. After a harrowing cross-country trip, Joel succeeds in delivering her to a Firefly-held hospital in Salt Lake City, only to learn that the surgery she’s scheduled for will kill her. Unwilling to lose her, he fights his way through the Fireflies and escapes with an unconscious Ellie, dooming countless future Infected. When Ellie awakes, Joel lies, assuring her—but not completely convincing her—that the Fireflies were unable to create a cure.

The core of The Last of Us—and, to a lesser extent, its sequel, which debuted on PS4 on Friday, almost two months after many of its plot points leaked—is the relationship between Joel and Ellie. Although at first Joel treats her like cargo, he comes to see her as a substitute for the daughter he’d lost. As Ellie matures, she gains confidence and competence. At times, their roles reverse, and she becomes the caretaker. By the end, each finds out how far they’ll go to keep the other alive.

The original wasn’t exactly light entertainment: It started with the death of a child and transitioned into suicide, cannibalism, and hordes of horrific monsters. But beneath the bloodshed, The Last of Us was a story of survival, bonding, and redemption. Part II is a story of revenge, alienation, and depravity. Both visually and thematically, it’s far darker than the first game. I dealt with the gloom on the surface by boosting the brightness and shining the flashlight liberally. There was no way to lighten the tone.

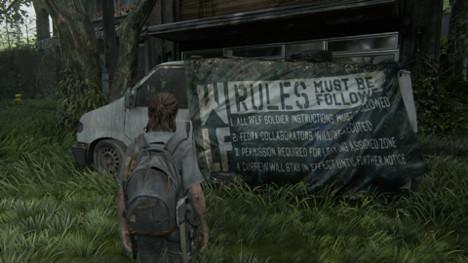

Unlike The Last of Us, which features one of the most wrenching openings of any game, Part II eases us into the torment. Five years after the end of the first game, a 19-year-old Ellie has settled into her relatively comfortable life in Jackson, Wyoming, flitting from nighttime flirtations to daytime patrols. A snowball fight provides a playful combat tutorial and, like the toy-gun target practice in Nathan Drake’s attic in Naughty Dog’s Uncharted 4, foreshadows more lethal encounters to come. After a traumatic event disrupts her routine, Ellie and her new girlfriend, Dina, set out for Seattle, where most of the campaign takes place. There they fend off not only Infected, but competing factions of ruthless survivors: the Seraphites, or “Scars,” a religious cult, and the Washington Liberation Front (WLF), or “Wolves,” a well-armed group that overthrew the agency in charge of the local quarantine zone.

Like its predecessor, The Last of Us Part II excels at setting the scene. Four years further on from Outbreak Day, the urban landscape looks even worse for wear. Buildings are decrepit to the point of collapse. Rivers run through Seattle’s streets, eroding roads and carving pedestrian paths into islands. Trees sprout up next to cranes that will never complete their construction. Rusted trucks squat on highways that barely hint at pavement through thick green brush. Nature is quickly reclaiming mankind’s creations. After meeting the morally compromised humans who remain, I started rooting for nature to finish the fight.

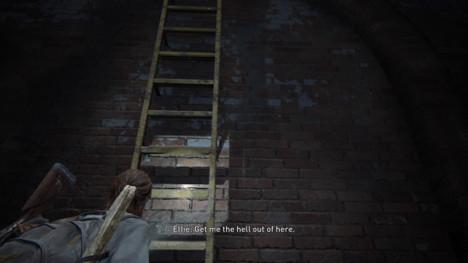

The mechanics of combat, exploration, and skill progression in Part II are almost unchanged from the first game. Aside from some Uncharted-esque chase or escape sequences, the pace is deliberate by design: Doors that lead directly to where you want to go are invariably locked, leading to acrobatic detours and searches for generators and keycodes. (“Of course it’s blocked,” one character says after rerouting for the umpteenth time. “That’d be too easy.”) Bullets are scarce, which makes stealth the preferred approach. Enemies are competent in combat but incapable of detecting a crouching assailant a few feet away—a necessary concession in a game that pits the player against hundreds of armed opponents, but one that turns each skirmish into a protracted, repetitive series of sneaks punctuated by stabbing or strangling. Ellie, who shares Joel’s superhuman hearing in “listen mode,” has learned a few tricks that the old Joel never knew: She can go prone, dodge melee attacks, and shoot from a supine position after taking a bullet. Her adversaries also boast new abilities: The Scars coordinate their movements by whistling like the Saviors on The Walking Dead, some of the Wolves walk dogs that sniff out your scent, and two new forms of Infected lurch and spasm inside spore-ridden lairs, more grotesque than ever.

Like Uncharted 4 and God of War, The Last of Us Part II dips a toe into a non-linear level structure. Most areas funnel characters along predetermined routes, but at times, the game relaxes a little and allows players to explore optional locations or choose which objective to travel to first. The environments are bigger and grander than before, and Naughty Dog’s customary polish still suffuses every inch. Although no graphical flaws, frame-rate hiccups, or noticeable bugs mar the immersion, an inevitable video game-ness inserts itself. Grabbing snacks still instantly restores health, and trying a door that doesn’t open adds a floating “LOCKED” in red text to the screen. For someone who’s hell-bent on making people pay, Ellie spends a lot of time rummaging through cabinets and digging through drawers to find crafting materials and items that unlock upgrades. Most disconcerting, the Infected that have human faces reappear pretty often; I slaughtered several that looked exactly like the dressed-down lady below.

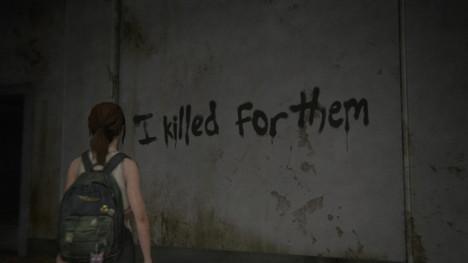

What Part II perfectly captures is the unrelenting anxiety of existence in a world where annihilation lurks in every dark corner. Boarded-up windows and blockaded doors echo futile attempts to keep oblivion at bay. No sanctuary seems secure—a stronghold called “Haven” goes up in flames—and to travel unaccompanied, as Ellie often does, seems appropriately reckless. An assignment to cross hostile territory or clear out a floor full of Infected induces the dread that it would in real life. As I progressed through the game, Ellie let out an incessant string of “Oh fucks” and “Fuck mes,” giving voice to my own inner monologue. The first game held out hope that Ellie and Joel could bring about a better world, but Part II’s protagonists are resigned to nothing they do mattering to anyone outside of their immediate circle. Entropy can’t be beaten: “Two down, millions to go,” one character remarks after killing a couple of Infected. This screenshot sums up the experience.

Given that oppressiveness, Part II isn’t often “fun” in the sense that Frogger or Fortnite are. (In fairness to Naughty Dog, their goal was to make the game “engaging.”) Had I not been trying to finish before the release date, I would have taken more mental breaks. Most games supply stress relief, but Part II is a harrowing test of endurance that calls for a second game on the side to deliver relief from the first.

For that reason, the game’s timing could have been better. Animal Crossing was a soothing respite from a barrage of bad news, and Doom Eternal was a way of faux-violently venting frustration about microscopic or systemic foes that couldn’t be conquered so easily. The only solace The Last of Us offers is a reminder that even now, conditions could be worse. That its punishing campaign coincides with a summer when happiness is historically scarce only magnifies its misery-inducing effect. It’s not Naughty Dog’s fault that a game begun in 2014 debuted at a time when widespread infections, quarantines, and curfews were off-screen realities, but these unsought synchronicities pop up even when players may wish they wouldn’t.

Part II’s exquisite craftsmanship imposes a separate psychic burden. As I always do during Naughty Dog’s games, I marveled at many minor touches that studios with smaller budgets and less exacting standards wouldn’t contemplate including. Joel reflexively lifts his arm to shade his eyes when he’s facing the sun. Ellie automatically raises and lowers her hood when she ventures out in the rain. These tiny indicators of quality, and many more, are present because someone put them there, sometimes at considerable cost to their health or happiness. In his review of The Last of Us for Grantland, Tom Bissell noted that “these glorious games are, in real and measurable ways, born of human misery.” Jason Schreier made that misery more measurable when he documented Naughty Dog’s culture of crunch in a feature for Kotaku in March. Despite multiple delays and the excising of a multiplayer mode that may still surface somewhere, Part II’s development was a grueling gauntlet of long days and all-nighters. Bruce Straley, who directed The Last of Us and earns a thanks in Part II’s credits, cited burnout as his reason for departing Naughty Dog after finishing Uncharted 4, and other Naughty Dog designers have made the same decision.

I asked Schreier how he handles the moral dilemma of playing or lauding a product of crunch. “I think most developers would rather people enjoy the fruit of all those hours than feel bad about it,” he said. “That helps me compartmentalize.”

The Last of Us Part II is a game made under difficult conditions that depicts difficult conditions and debuted under difficult conditions. That overriding bleakness makes its small snatches of peace more precious. Visits to vestiges of a less lawless world—often in flashbacks—evoke the original’s giraffe scene. Ellie sometimes takes a break from bludgeoning bloaters to strum a guitar. Naughty Dog’s deft feel for dialogue is intact, and the acting by Ashley Johnson, Troy Baker, and others is equal to the task. Idle, unforced banter between characters—whether wistful speculation about what the old world was like, or the teasing that takes place in more normal milieus—offers brief reprieves from the grimdark march to immorality, although even in tender, intimate moments, the characters’ harsh reality intrudes. In bed, Ellie and Dina compare their respective scars; on horseback, they reminisce about their first kills the way another couple would recount how they lost their virginity.

The Last of Us told a simple, satisfying story, ending on an ambiguous note that didn’t require clarification. The problem with Part II isn’t that it extends a story that stood on its own, but that it does so with the subtlety of a shotgun shell. A lack of fun would be forgivable if Part II were saying something other games haven’t said more skillfully, making us question our motives or tastes, or blurring the boundaries between right and wrong. But it’s clear from the get-go that no good can come of this quest, and the hours that follow only hammer home a message that seems self-evident: Violence and vengeance beget further violence and vengeance, spreading the sins and the suffering around.

It takes four hours to read The Road and two hours to watch the movie version, but The Last of Us Part II is a 30-hour ordeal, roughly double the length of its predecessor. According to franchise creative director Neil Druckmann, even some Naughty Dog devs “were just stuck on how violent it is and how dark and quite cynical it is about mankind.” Hauntingly rendered as the studio’s vision of a fallen future is, the appeal of wallowing in its world wears thin after several violent variations on the same theme. The only wish this fantasy fulfills is that after a few false endings, it does eventually end.

Part II’s padded playtime permits a more crowded cast and a thicker snarl of narrative threads. While The Last of Us kept a tight focus on its leading duo, Part II employs a creative and complex narrative structure that unfolds via opposing, playable protagonists and hops backward and forward in time. (Ellie’s is the only face on the cover, but she sits out an appreciable portion of the game.) The upshot of the shifts in perspective is that there are bad people on both sides—or, in the most charitable interpretation, that there are formerly fine people on both sides whose moral compasses have long since swung away from magnetic north. The Scars and the Wolves both began with good intentions and became equally cruel and corrupted. Ellie and her new nemesis hold similar grudges and pursue almost identical desires. These parallels are apparent to us, but completely (and curiously) opaque to the participants, who lack any semblance of self-reflection or empathy.

The continuing tale of Joel and Ellie, who spend Part II reckoning with and suffering from the consequences of their past actions, remains the throbbing heart of this saga: Even as an older Ellie solidifies her individual identity, she applies what Joel taught her in constructive and destructive ways. The power of their pairing exposes the sequel’s struggle to establish any new relationships that rise to the same level. Although Part II’s WLF love triangle and trio of queer characters—one of whom is violently targeted for coming out as trans, another way in which the game traffics in trauma—yield a few compelling personalities, the need to service several subplots makes it difficult for their bonds to breathe and develop. Whereas the player was present for the first contact between Joel and Ellie, Ellie and Dina have a history we don’t see, and their leap from friends to inseparable lovers isn’t clearly laid out. And while Joel and Ellie travel together, Dina mostly stays on the sidelines, reduced to a symbol of the life Ellie won’t allow herself to lead. (The character clutter also pushes aside some of the world-building; much of the backstory of the Scars and the Wolves is buried in letters left on or near corpses.)

Ellie’s inability to see situations from anyone else’s perspective, understand how her actions affect others, or learn from her mistakes is frustrating for us, but I won’t police the plausibility of the behavior of an adolescent orphan in a nightmare full of fungus-human hybrids who’s survived dozens of near-death experiences and became a killer at 14. (Dina drew first blood at 10.) Ellie is pretty entitled to go on tilt. But the atrocities she perpetrates in Part II aren’t morally defensible or debatable in the way that Joel’s hospital spree was in The Last of Us. The hollowness at the heart of this game stems half from her actions and half from the fact that Naughty Dog doesn’t make us feel guilty for going along with them.

In 2018, Neil Druckmann told BuzzFeed, “We believe that if we’re invested in the character and the relationships they’re in and their goal, then we’re gonna go along on their journey with them and maybe even commit acts that make us uncomfortable across our moral lines and maybe get us to ask questions about where we stand on righteousness and pursuing justice at … ever-escalating costs.”

Part II didn’t make me question my stance on violent vengeance. (I’m, um, against it.) Nor did it make me feel queasy about committing acts that Naughty Dog dictated. Roger Ebert argued that video games would never be the artistic equals of movies or literature because he believed that the possibility of player choice was inherently in conflict with authorial control. But many makers of video games have exercised their authorial control to engineer meaningful choices. Telltale’s The Walking Dead let players decide whom to save or sacrifice. Spec Ops: The Line’s “Hanging Men” scenario gave players more than one possible response to an order to execute hostages. BioShock presented a choice between the morally “right” decision (saving the Little Sisters) and the personally empowering decision (harvesting then for more ADAM). While that choice ultimately didn’t matter that much, it still felt consequential.

During a boss fight with The Sorrow in Metal Gear Solid 3, the player must evade the ghosts of the enemies who Snake has killed. Players who’ve opted for a less lethal style find fewer ghosts to avoid; players who’ve killed indiscriminately relive (and have reason to regret) that approach. In The Last of Us Part II, you come across a soldier playing Hotline Miami (on a Vita, because only PlayStation platforms are apocalypse-proof.) In one disturbing scene, that game asked its players, “Do you like hurting other people?” In Hotline, the uncomfortable answer was yes—hurting other people felt fantastic. In The Last of Us Part II, the answer is “No, not really,” but there isn’t an option to do anything else.

Lifelike animation sometimes substitutes for an absence of alternatives. When one of Part II’s playable characters is about to snap a neck, she presents the panicked faces of her victims to the camera, as if to say, “Behold your handiwork.” I felt a twinge or two. But most life-or-death decisions are out of our hands. In one scene, Ellie wrestles with whether to torture a captive to extract information. (In both The Last of Us and its sequel, torture typically works, even when the victim has no incentive to talk.) The player has no say. Instead, an almost apologetically minuscule icon appears on the screen, demanding that one button be pressed.

This is a game that makes you kill a dog in a quick-time event, then transports you back in time to play fetch with that not-yet-dead dog, just in case you weren’t already down on dog-killing. (Yes, you can also pet the dog.) After enough of those manipulative, mandatory moments, I no longer felt anything.

Amid all of its handcuffing cruelty, Part II dispenses a smattering of memorable moments that many games never achieve. Some of its desolate vistas are breathtaking. Some of its fights are frantic. Some of its cutscenes and set pieces make me admire Naughty Dog’s audacity. If you’re in the right headspace, those highlights may make the journey worthwhile. Others might be better off waiting to watch it on HBO.

In one of the game’s many hidden texts, a writer quotes an optimistic maxim from a fictional rabbi: “For every turn away from a better world, there is often a strong correction towards it.” There’s a path to a possible Part III that could make this misery mean something, so if Naughty Dog decides to extend the series, Part II—or Part II Remastered for PS5—may serve a vital function in the context of a trilogy. As a sequel or a stand-alone experience, though, it’s a beautiful but disheartening slog. Some sordid stories expose greater truths, but The Last of Us Part II’s darkness doesn’t illuminate anything.