The NBA was ready to return with a flourish. After a thrilling end to the 1997-98 season—with the most-watched Finals in league history, culminating in the most-watched game on record—a financial dispute between owners and players led to a six-month lockout, arresting momentum from the Jordan years and placing the 1998-99 season in peril.

So when the lockout was finally resolved in January 1999, it made sense to look toward the league’s last great moment to start the season. Opening night would feature a Finals rematch between the Bulls and Jazz—what better way to plunge fans back into the thrills of professional basketball?

There was just one problem. While Karl Malone, John Stockton, and Jerry Sloan had stayed put in Utah, their Chicago counterparts were all gone. Michael Jordan, Scottie Pippen, and Phil Jackson were chased out of town by Bulls GM Jerry Krause and a combination of exhaustion, economics, and ego. Krause, and by extension Bulls owner Jerry Reinsdorf, wanted to rebuild, and there was no question what would happen to the three-time defending champions in the meantime.

So dismal were the new Bulls’ prospects that, despite the league’s best efforts, opening night’s ostensible centerpiece didn’t even air on national television. A TNT spokesman said at the time, “We didn’t look at that as a rematch of the NBA Finals because of the complete overhaul of the Bulls’ roster.” Added Kevin O’Malley, Turner Sports’ then-senior vice president, in an interview with the Chicago Tribune, “We said, ‘We can’t take that game. That game could be over by halftime.’”

Indeed, Utah led by 15 at the half that night—just the first installment of three months’ worth of misery for the Bulls. Chicago didn’t just miss the playoffs for the first time since Jordan was in college, after six titles in eight years; at 13-37, it finished with the Eastern Conference’s worst record, and what was then the worst winning percentage in franchise history.

“It was worse than I thought it would be,” Ron Harper, one of the few returning Bulls, said after the season. Or as Bulls big man Dickey Simpkins put it a bit more colorfully after Chicago lost both games of a back-to-back by a combined 52 points, “Some days you’re the pigeon and some days you’re the statue. We’ve been the statue the last two days.”

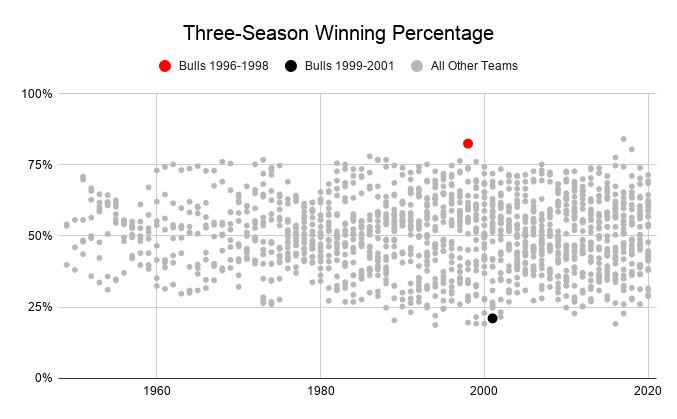

The Bulls’ season-long collapse is unprecedented in NBA history. In the three seasons from 1995-96 through 1997-98, the Bulls won 83 percent of their regular-season games—the second-best stretch for any team in league history, trailing only the 2014-15 through 2016-17 Warriors (84 percent). In the three seasons starting with 1998-99, though, the Bulls’ win rate dropped to 21 percent (45-169)—the seventh-worst mark ever recorded.

The Last Dance documentary series wrapped up Sunday by detailing the climactic conclusion to those 1998 Finals—but it’s hard to imagine anyone investing in a 10-part recollection of the Bulls season that followed. That job will stay here instead, as we take a retrospective look at the franchise’s day-to-day post-Jordan reality, complete with confusion over the triangle, a host of unwelcome records, and locals left adrift after the last dance had played.

By the start of the 1998-99 season, the only previous champion in league history to miss the following postseason was Boston after Bill Russell and Sam Jones retired. And at least those Celtics, with multiple future Hall of Famers still on the roster, finished a respectable 34-48 with a near-even point differential. The 1998-99 Bulls could make no such claim.

After the lockout ended, Krause started his rebuilding plan with the dissolution of Chicago’s championship roster. Out of the eight Bulls who had averaged at least 10 minutes per game in the 1998 playoffs, only Harper and Toni Kukoc returned. Phil Jackson left almost as soon as the playoffs ended, and Jordan announced his second retirement on January 13. From January 21-23, after the lockout’s transaction freeze ended, the Bulls sign-and-traded Pippen, Steve Kerr, and Luc Longley, and released Dennis Rodman and a handful of reserves.

New faces included former slam dunk contest winner Brent Barry, who had signed a six-year contract worth $27 million in free agency, and a host of unproven players who would never make an impact in the NBA and were so unfamiliar that they needed a refresher on basic NBA rules. Harper remembered thinking, upon entering the locker room for the first time, “Who are these guys?”

Bulls Rotation, 1998 vs. 1999

With so many key figures from the 1998 champions gone, the Bulls didn’t hold the traditional public ring ceremony. Even the club’s famous pregame introduction routine changed—PA announcer Ray Clay received instructions to welcome “your Chicago Bulls” as the Alan Parsons Project thumped throughout the United Center, rather than “your world champion Chicago Bulls.”

For everyone involved, it was hard not to compare the new players to the victors who had populated the home locker room just months earlier. Before the opening night game against the Jazz, new coach Tim Floyd showed his team how Jordan, Pippen, and Rodman had defended Utah’s offensive actions the previous season; it was the only film he had. “I wish they were here tonight,” the new coach lamented. Meanwhile, Sports Illustrated’s Rick Reilly described a discomfiting scene at practice: “Tex Winter, the Bulls’ longtime assistant coach, keeps yelling in practice, ‘No, no, no! Scottie would’ve stepped up, and Michael would’ve popped out there!’ (‘I need to stop doing that,’ Winter says. ‘It’s not fair. I don’t see a lot of Scotties and Michaels out there.’)”

The Bulls’ largest problem was their offense, which early in the season scored 71 points against the Hawks, 68 against the Knicks, 76 against the Spurs, and 67 against the Hawks all in a row. In that Knicks loss, the Bulls set franchise lows for points in a half (23 after intermission) and made field goals (21)—and somehow, that wasn’t even their worst showing against the Knicks that month. On February 21, the Bulls tied a franchise low for points in a 79-63 loss at Madison Square Garden.

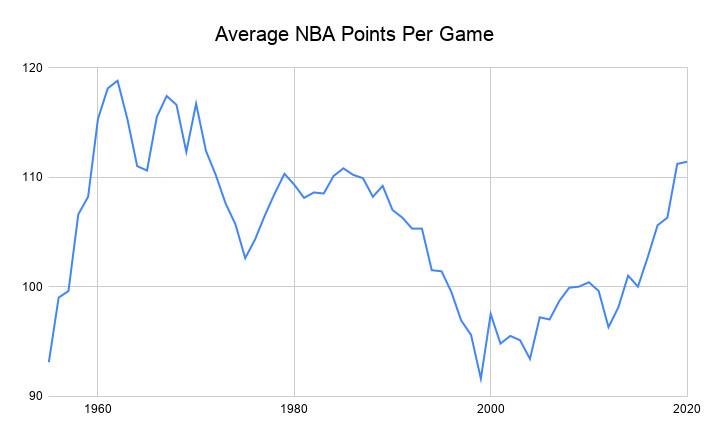

By season’s end, the Bulls had scored 81.9 points per game, the worst mark since the invention of the shot clock in 1954. No other team has finished within even two points of the Bulls. Given the direction of NBA offenses, Chicago’s record for offensive futility might never be broken.

The issues were a mix of leaguewide and team-specific factors. The lockout didn’t merely sap Chicago’s ability to score; it tarnished the whole league’s offensive structure. “If you made major trades in the offseason, you had so little practice time that it was hard to get the new players incorporated rapidly,” then-Knicks coach Jeff Van Gundy remembered later. Fifty games were crammed into 90 days, which meant teams played many games with zero rest and even back-to-back-to-backs. “I can’t play three days in a row. I can’t have sex three days in a row,” the Rockets’ Charles Barkley memorably quipped.

Many players arrived out of shape, unprepared for the rigors of a normal NBA schedule, let alone this condensed monstrosity. Because of both the exodus of championship veterans and the truncated offseason, only six of Chicago’s players were under contract the first day they were supposed to practice, so the team had to cancel. “Well, we didn’t get anybody hurt today,” Floyd joked. Yet even when the season began, the Bulls grew so fatigued, so quickly, that he canceled another practice after just four games.

Teams responded by slowing the game and missing shots by the bushel. The league’s pace fell to its slowest crawl on record, while offensive efficiency on a per-possession basis fell to its lowest figure since the introduction of the 3-point line. Those two factors combined to drop overall scoring to its lowest level in the shot-clock era: just 91.6 points per game.

But Chicago also had its own problems. The new Bulls struggled to navigate their offensive philosophy, with triangle architect Tex Winter still on the coaching staff and Krause pushing Floyd to install his principles. Without Jordan, Pippen, and the other departed veterans, they weren’t suited to score with such an intricate system. The triangle, longtime Bulls writer Sam Smith noted on the eve of the season, “requires a good high-post passer, which the Bulls don’t have, and good stand-still jump shooters, which the Bulls don’t have.”

“We’re kind of like Keystone Kops running into each other,” Barry observed in February, and Floyd grew so desperate for anyone who understood the offense that when Kerr and the Spurs came to town, Floyd yelled out, “Hey Steve, tell ’em what to do in the triangle.” The team had learned only 30 percent of the offense by the start of the season, the coach said. (Floyd, for what it’s worth, didn’t necessarily act this way out of his own volition; he said recently, “When I got there, they forced me to run the triangle offense and keep Tex.”)

Seemingly everyone questioned the decision to stick with the triangle, even opposing players. After Atlanta held Chicago to 33 percent shooting in an early 83-67 win, Hawks center Dikembe Mutombo suggested the Bulls should change their approach with Jordan gone. “When you change the chef,” he said, “you change the menu.” But the menu remained the same, and the food became stale—and not merely in metaphor. A United Center promotion gave fans free tacos after 100 points in a home victory, but the Bulls reached triple digits at home just twice in 25 tries. The first time it happened resulted “in the loudest cheer in the building all season,” the Tribune reported.

All the while, it was impossible to forget the man who had left the building. Jordan returned to the United Center only once during the 1999 season—but to watch the Blackhawks, not his old team. He didn’t even stop by for a tribute ceremony for Phil Jackson, choosing to prerecord a video message for the scoreboard instead.

Jordan didn’t stop ribbing his former coworkers, though, as he had when he was still a leader of the team. Assistant coach Frank Hamblen said that after that loss against the Hawks, Jordan called and told him, “I can score 67 points in a game—c’mon.”

The post-Jordan Bulls weren’t completely devoid of highlights. Kukoc, a former Sixth Man of the Year, assumed an expanded role and averaged 18.8 points, 7.0 rebounds, and 5.3 assists per game, all career highs. The much-maligned Simpkins played well in the middle. Randy Brown beat the overtime buzzer to steal a game in Toronto.

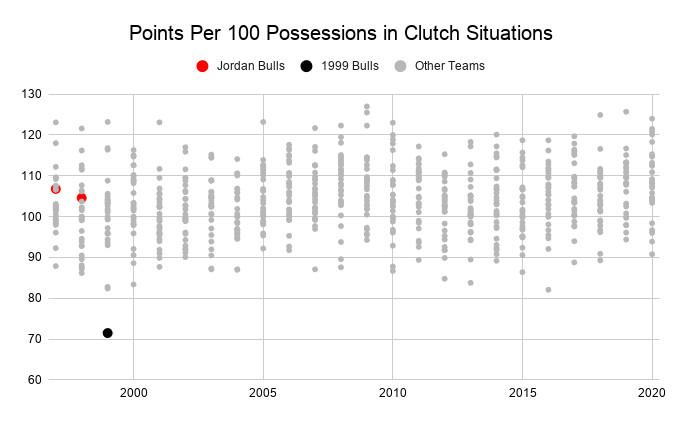

But those glimpses of sunlight were few and far between. Brown’s game-winner, for instance, was just about the only example of worthwhile late-game execution the team saw all season. Through the full schedule, the Bulls were astonishingly awful in close games, scoring 71.5 points per 100 possessions in “clutch” situations, as defined by NBA.com/Stats. That’s more than 10 points worse than every other team in the site’s database, which dates back to 1996-97.

Other teams, meanwhile, were thrilled to stymie all of Chicago’s efforts after years of losing to the champs. “For all the years they destroyed people, it’s payback time,” Minnesota’s Sam Mitchell said. Utah’s Jeff Hornacek scoffed, after two consecutive Finals losses, at the possibility that the new Bulls might warrant warmer feelings. “Sympathy?” he asked. “For a team that’s won six championships? Are you kidding me?”

The worst blight of all came against a team with as much reason for revenge as anyone after multiple playoff defeats to Chicago throughout the decade. Miami was a rough matchup for a team that struggled to score. The Heat were a plodding, well-structured, Pat Riley–coached group that guarded the rim with ferocity. Led by center Alonzo Mourning, who’d be named the Defensive Player of the Year and finish second in MVP voting at season’s end, they allowed the second-lowest scoring average in the entire shot-clock era (84.0 points per game, trailing only the 1999 Hawks’ 83.4).

And by the time the Bulls first played the Heat in April, they were already hurting. Barry was out with a sprained ankle; Harper was in his first game back after dislocating his left index finger and hyperextending his right knee on the same play; and Kukoc and Brown were below 100 percent as well after missing recent games with injuries. The season’s accelerated timeline didn’t leave enough recovery time, and the Bulls suffered worse than any other team. Chicago used 24 different starting lineups in 50 games; no other team went higher than 20. Even Benny the Bull found his way to the injury report after twisting an ankle.

So an immovable object met an eminently stoppable force at the United Center, and NBA history emerged. The Bulls fell behind 15-0 in the first quarter and missed their first 14 shots; they had just eight points after the first quarter, 23 at halftime, and 33 after the third quarter. And after turning the ball over twice in the final seconds, they set a new record: 49 points in a single game, fewest for any team in the shot-clock era.

The individual statistics bordered on obscene. Mourning collected four blocks before Chicago made a single field goal. The Bulls shot 0-for-9 on 3-pointers in the game and 13-for-24 on free throws, and finished with more turnovers than made field goals. Their leading scorer was reserve big man Kornél Dávid, nicknamed “Hungary’s Michael Jordan,” with 13. The real Jordan had scored at least 50 points 38 different times in a Bulls uniform.

Perhaps the worst part of the Bulls’ new record was the situation from which they had wrested it. The previous low for points in a game in the shot-clock era was 54—set by Utah in the 1998 Finals, when Chicago coasted to 96-54 win in Game 3. There’s no better illustration of how far and how quickly the Bulls had fallen; in less than a year, they had gone from setting a record on defense to letting another team break that same record.

“I don’t know what Michael would say about this,” Harper said after the loss. Kukoc could barely form the words to describe his emotions: “It just doesn’t feel good right now. There’s nothing else you can say. It just hurts.”

It’s impossible to overstate the Bulls’ importance in the league’s ecosystem throughout the 1990s. To this day, the four highest-rated Finals on TV all involved the ’90s Bulls, and in 1997-98, Bulls merchandise accounted for an estimated 50 percent of the entire league’s sales.

Starting with that missed broadcast on opening night, however, it was clear that the 1998-99 season would look different. This time, NBC broadcast only one Bulls game all season—a Knicks vs. Bulls clash that aired only in the New York and Chicago regions, and with a backup announcing team. TBS and TNT didn’t show any Bulls games at all.

On the road, where the Bulls once attracted crowds in the hundreds and thousands every time they arrived at an opposing arena or hotel, they now traveled in anonymity. “Things are a little different around here,” center Bill Wennington said. “It’s no longer a traveling circus. It’s more like we’re traveling salesmen.”

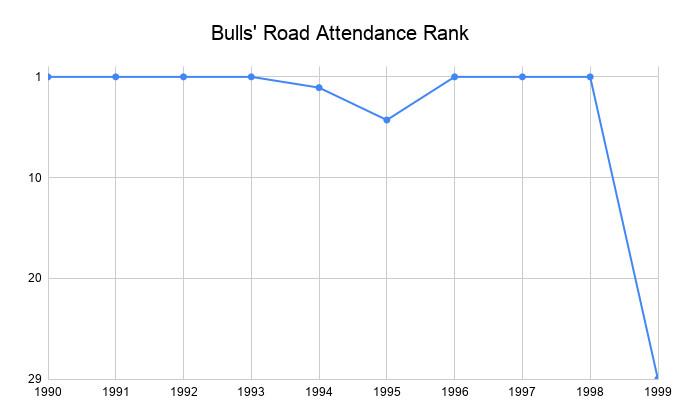

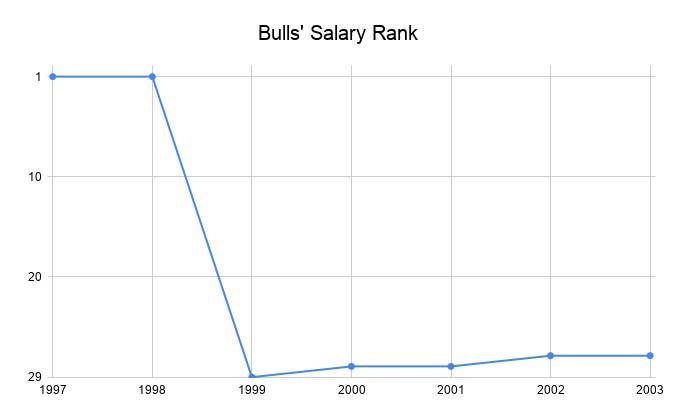

Scalpers had to offload Bulls tickets for one-tenth the price of the previous season. The drop-off in attendance for away games was as extreme as possible. The Bulls ranked first in road attendance every season in the ’90s that Jordan played, dipping to second and fifth in his baseball years. Then in 1999, according to Basketball-Reference’s data, the Bulls ranked 29th in road attendance in a 29-team league.

Although the Bulls maintained their sellout streak at home, every other indicator of local interest plummeted in concert with the team’s fortunes. Chicago bars and restaurants cited sales drop-offs of up to 40 percent because of the lack of basketball spectators, and TV ratings with the local Fox affiliate dropped by more than half. When baseball season started, TV and radio stations in the area elevated White Sox and Cubs games to the top spots if games overlapped, bumping the Bulls to a lesser network or tape delay for the first time anyone could remember. And within two weeks of the season’s start, the local CBS affiliate stopped sending a crew to cover road games because, as the sports anchor put it, “How many times can you run interviews of guys saying, ‘We stink’?”

Media outlets had to change the framework for their Bulls coverage. TV play-by-play man Tom Dore called broadcasters from worse teams to learn how to handle extended garbage time on the losing end, for instance, and the Tribune, the largest local paper, dropped the Bulls off the front page of the sports section within the first month, bringing them back only for stories like the rumors of Jordan buying a stake in the Charlotte Hornets. (The day after the team’s first home win, the Tribune instead led with a college game between DePaul and UNC-Charlotte.) At least the man who wore the Benny the Bull mascot costume could schedule a move in June, rather than waiting until August because of his playoff responsibilities.

Former Bulls All-Star and then-TV analyst Norm Van Lier might have summed the depressing situation best. Near the end of the season, when explaining his more subdued broadcasts of late, he said, “It’s been tough getting pumped up and maintaining an energy level night after night so I can talk about a team that really just doesn’t have it. It was so easy before.”

The 1998-99 season ended in dispiriting fashion, with the final two losses coming by a combined 64 points. “A time to celebrate: Bulls’ season is over,” the Tribune crowed. But after the season, there was actually some optimism in the organization that brighter days lay ahead. Chicago had successfully slashed payroll to position itself for free agency. The team even won the draft lottery. “All I know is next season is going to look like Palm Beach,” Floyd said, smiling, a few days after the final game.

He was wrong. Despite enjoying a Rookie of the Year–winning season from no. 1 pick Elton Brand, the Bulls were even worse in 1999-2000 (17-65), then worse again in 2000-01 (15-67). They kept the league’s worst offense in both seasons.

Krause’s attempts to replenish the roster with external stars failed miserably. In the 1999 summer, the club’s only free-agent signees were three reserves: Fred Hoiberg, Will Perdue, and B.J. Armstrong—the latter two mere reminders of the glory days. The following summer, as they missed out on the likes of Tracy McGrady and Grant Hill, the Bulls inked Ron Mercer and Brad Miller. “The Bulls’ plan following Jordan was to get farther below the salary cap than any other team after this season and then sign two of the best free agents,” Sam Smith had written in 1999. In one sense, Krause was ahead of his time as a roster architect. But none of his actual signees qualified for that designation.

At least Reinsdorf saved a heap of money on payroll, including a salary dump of Barry after just one muted season in Chicago; by one accounting, he took in more than twice as much profit from the 1998-99 season as he had in 1997-98, despite the reduction in games and lack of playoff income. After running the highest payroll in the league in Jordan’s last two seasons, the Bulls ranked at or near the bottom for the next half-decade.

It didn’t take long for Bulls fans to turn on the two Jerrys. At the ceremony to honor Jackson, the former coach thanked Reinsdorf and Krause and the home crowd “booed thunderously,” wrote Tribune columnist Skip Bayless.

In the local paper, letter after letter to the editor reflected fans’ criticism of those they blamed for forcing apart the title-winning roster. One critic went after Krause with as much biting panache as Jordan himself could muster.

In January 1999, Reinsdorf suggested the Bulls would return to the conference finals within two or three years. It took them a dozen. Nobody from the 1998-99 roster remained on the team even in 2004-05, when the so-called Baby Bulls reached the playoffs. Of the key figures, Kukoc and Harper had been traded and released, respectively, by February 2000; Floyd resigned on Christmas Eve 2001; and Krause resigned in April 2003.

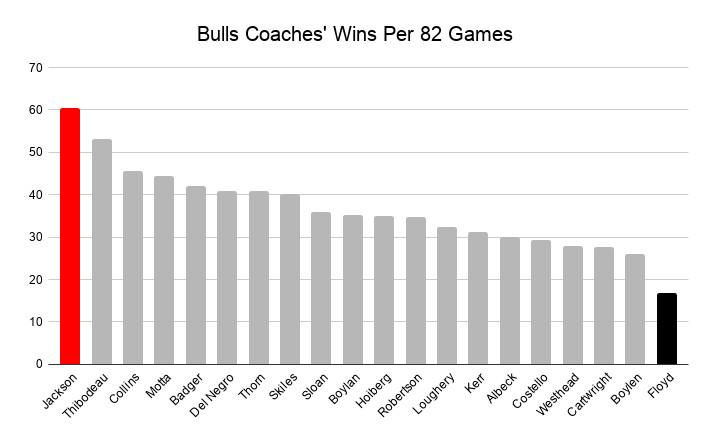

Floyd might have had the most sympathetic situation of the bunch. Saddled with a porous roster, inert offensive system, and Jackson’s giant unfillable shoes—he was booed at Chicago’s very first intrasquad scrimmage—his life as Bulls coach was a series of slights. Floyd finished his Bulls tenure averaging 17 wins per 82 games, worst in franchise history. Jackson, his predecessor, averaged 61 wins per 82, the organization’s best. (Although not quite as extreme, the most recent Bulls switch stands out, too—Tom Thibodeau is second best for the franchise, Jim Boylen second worst.) The poor guy was even ejected on his birthday in 1999, and subsequently fined $5,000.

Even now, 20-plus years later, the Bulls’ collapse stands alone in swiftness and size. Cleveland came closest the first time LeBron James left; the 2010-11 Cavaliers went 19-63, and their day-to-day reality was even worse. At one point, they lost 10 games in a row, then beat the Knicks in overtime, then lost 26 more games in a row to set a record. (The Process 76ers later tied that 26-game record.)

But those Cavaliers hadn’t won a championship yet, and they fell apart because of a Decision from one player. The Bulls’ was a controlled demolition when the team had a realistic chance at a fourth title in a row. The choice was baffling at the time and even more so in retrospect, knowing the unfortunate outcome; sure, the Bulls might not have won again in 1999, but it’s impossible to imagine a worse next half-decade for the franchise than the one it actually experienced. The Bulls fully transformed from the pigeon to the statue, and they stayed that way for quite some time.