After two months of COVID-19–induced inactivity, jump-starting the MLB season was always going to be a tricky proposition. Professional baseball is a logistical high-wire act in the best of circumstances, and at a time when every human interaction carries a risk of spreading illness, the situation is even more delicate. To put on games in empty stadiums, the 30 MLB teams, the league office, and broadcast partners still need tens of thousands of people to work together. Another small army of workers is required to feed, house, and transport the players from city to city.

And judging by the proposal MLB presented to the MLBPA on Friday, the complications of reopening baseball go far beyond just that.

The 67-page illustrated manual reportedly focuses on the health and safety measures necessary for a return to play. According to the proposal, those include players, coaches, and other on-field personnel undergoing coronavirus tests multiple times a week, and front office personnel being subjected to monthly blood screenings for antibodies. Players would receive daily temperature checks both at home and at the ballpark, and anyone who reports a body temperature of 100 degrees or higher would be put into isolation. The manual also includes diagrams indicating where coaches and players would be allowed to sit in the dugout, and guidelines on how far apart they’d have to stand for the pregame national anthem and the seventh-inning rendition of “God Bless America.” (For some reason, we’d still be playing music between innings in front of empty stands.)

Per the proposal, any ball that’s touched by multiple players during the course of play would be discarded, and all team meetings must be held either outdoors or via video conference to reduce unnecessary physical contact. Likewise, postgame buffets and dugout water coolers would be replaced with individually packaged meals and water bottles. Players would be strongly discouraged from showering at the team facility, fraternizing or fighting with opponents, and even spitting. America put a man on the moon, so maybe it can eliminate dip and sunflower seeds from big league dugouts.

This protocol, or one like it, might enable MLB to become operational by early July—if the league can finalize a deal with the union and knock down these logistical pins by the proposed start of the second “spring training” in mid-June. But as ESPN’s Jeff Passan detailed in his Sunday column, nothing about this plan would allow the league to operate normally. And even this meticulously considered option still has holes.

The most obvious question is how strictly rules will be enforced. Would players be fined for spitting or high-fiving, or is it enough to trust everyone to behave responsibly? Can players reasonably live and work under such strict controls over where they go and what they do? Maybe a substantial majority are willing to accept restrictions if that’s the cost of returning to play safely, but even in that case life under the proposed COVID-19 protocols would be uncomfortable and awkward.

Then there’s the very real and yet largely unspoken vulnerability of this plan: For all the thought the league higher-ups seem to have put into this, when and how MLB returns to play depends mostly on factors that neither the league nor the players can control.

Whatever the league does to limit the spread of the virus inside stadiums, the United States’ overall response to this crisis has yet to yield results like those in South Korea, where the KBO has been up and running for two weeks. While the virus is not totally under control there, it’s at least less prevalent than it is here. Former Astros and Braves outfielder Preston Tucker, now of the Kia Tigers, told the Houston Chronicle that strict isolation protocols are easier to abide by within South Korean stadiums because serious preventive measures have made it possible to return to something approaching normal life outside the stadium.

Beyond that are real issues of public health and social equality. The proposed MLB protocol splits employees into three tiers: Players, coaches, and on-field staff in Tier 1, with the most rigorous testing protocols; front office personnel in Tier 2; cleaning crews, groundskeepers, and other support staff in Tier 3, with the fewest protections and requirements on testing. Would these workers be less protected because they’re truly at a lower risk? Or merely because they’re seen and paid less?

Then there’s the issue of the more than 10,000 tests a week MLB would need to carry out this plan. The league is running its own testing facility out of a lab in Utah, and if this proposal were to be implemented, it would run additional coronavirus tests free of charge for health care workers and first responders in all 26 MLB markets “as a public service.” But there are plenty of logistical and ethical questions that come with that. At a time when testing for the general public is still extremely limited, where would these thousands of tests come from? How many would actually go to health care workers? And would it truly be a public service when those additional tests would be conducted, at least in part, to insulate the league against charges that it’s sucking up medical resources?

It’s become an article of faith that having baseball back would offer some palpable morale benefit to American society; while that assertion is self-serving and overstated, there’s probably at least some truth to it. But through this proposal, MLB has unintentionally invited the question of whether the intangible benefit of watching a midweek Reds-Cubs game does more for the public good than the tangible benefit of making tens of thousands of coronavirus tests available to the population at large. The answer to that ought to be enough to give the league pause. Plus, any finalized return-to-play protocol would require both the league and the union to come up with solutions to immense logistical and moral issues. And the road to reopening wouldn’t get clearer or straighter after that.

When crafting a safety protocol, the interests of the league and the players are pretty much in line: Both want something that’s practicable enough to bring baseball back relatively quickly, and both want to protect the players and the public from COVID-19. While there might be disagreement on the specifics, the parties are united about the overall goal, which should make it easier to agree to a plan.

Yet the league is also attempting to slash costs and offload financial liability onto others. MLB has already gone against the wishes of its scouts and GMs by truncating the draft to save a few hundred thousand dollars per team, even though there will be an immense cost in the quality of scouting and player development. The league is also forcing through an unpopular plan to shutter some 42 minor league teams in an additional cost-saving measure.

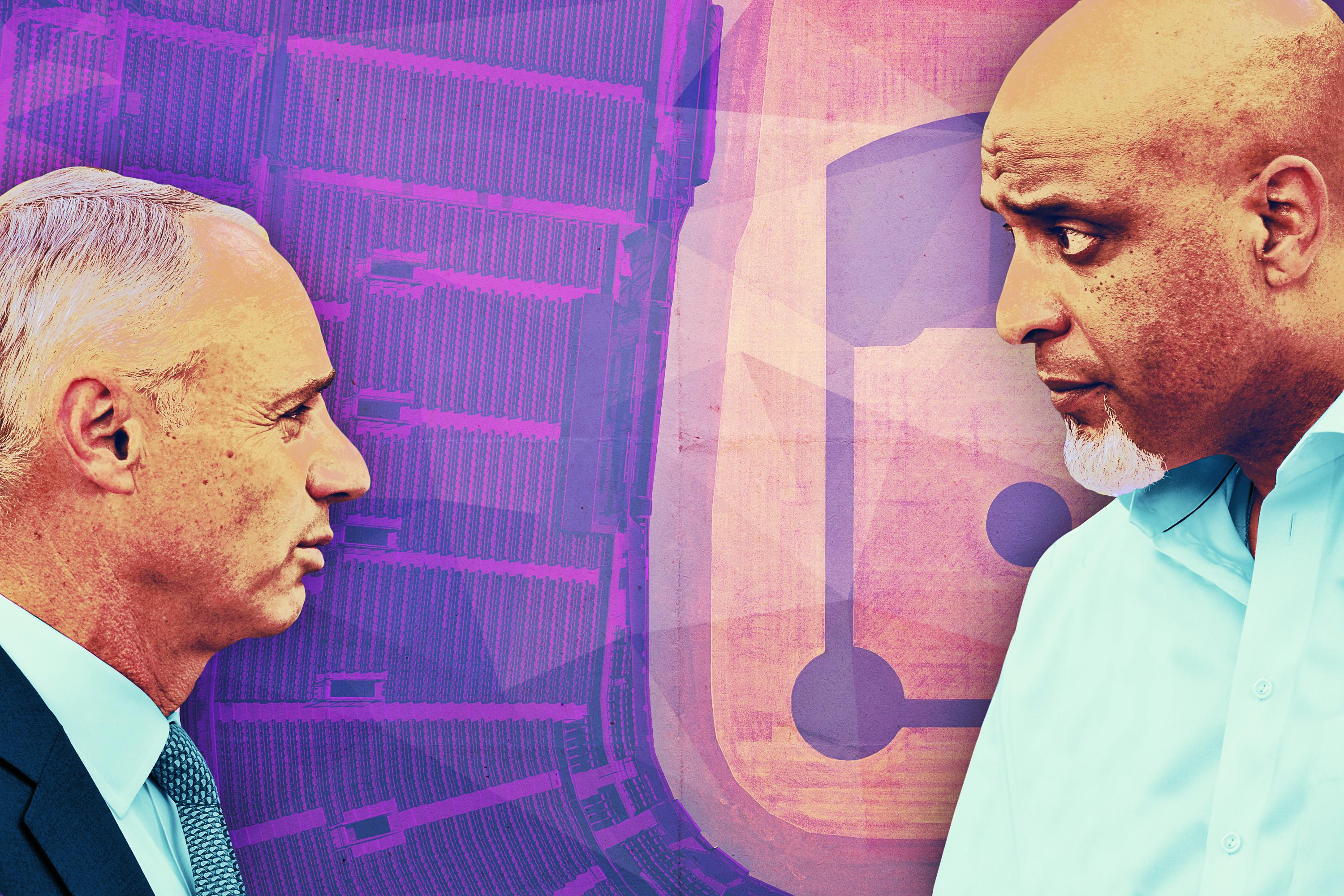

And even though the league and the MLBPA agreed in March that players would be paid on a pro rata basis in a shortened season, Bob Nightengale of USA Today reported last week that MLB is kicking around a proposal that would force players to take on more of a financial risk. That plan was not formally presented to the union at either their Tuesday meeting with the league or in the Friday session in which the health and safety protocol was proposed, but if it were to go into effect, it would tear up the existing agreement and tie players’ pay to league revenue.

The MLBPA would almost certainly reject this out of hand. Last week, MLBPA executive director Tony Clark said, “A system that restricts player pay based on revenues is a salary cap, period,” and MLBPA has fought against that concept since its inception. Although the revenue-sharing proposal was never officially submitted, a few players who saw the report spoke out against it. Reds pitcher Trevor Bauer called it “laughable,” while Rays pitcher Blake Snell said on his Twitch channel that it’s not worth it to risk his life for reduced pay.

That statement made Snell a momentary pariah in certain corners of the sports media, because an off-the-cuff response from a 27-year-old on a multiyear contract is easy for some people to mock. But the substance of Snell’s comments—that this stipulation would represent MLB going back on its word, and that players would bear a substantial risk by returning to play amid a pandemic—is spot on. Moreover, it mirrors not only Bauer’s sentiments, but those of Nationals reliever Sean Doolittle, who expressed similar concerns about health and safety in a Twitter thread last Monday. When asked about Snell’s comments, stars such as Bryce Harper, Nolan Arenado, and Clayton Kershaw all stood by the 2018 AL Cy Young Award winner.

One aspect of the league’s financial situation that was shared directly with MLBPA, according to the Associated Press, is that MLB expects to lose about $640,000 per game by playing without fans. The league is publishing this number seemingly in an attempt to nudge players into taking less than their fair share this season. But to understand why a multibillion-dollar league would put this kind of financial onus on its players, more context is required.

That report doesn’t appear to include the hundreds of millions of dollars MLB clubs make through real estate investments and other outside ventures, though it does acknowledge a big chunk of the league’s expenses comes from paying down billions of dollars in debt—as much as $7.3 billion by the end of 2020. If the revenue-sharing proposal is ultimately presented to the players, it would amount to the owners—who have billion-dollar franchise valuations along with billions in annual revenue—asking their sole marketable product to effectively bail them out.

For Opening Day to take place in early July, the MLB and MLBPA have to not only iron out the particulars of a player safety protocol, but also find an economic middle ground. And they have to do it in the next few weeks, all with the knowledge that this could be for naught if conditions across the country don’t improve. MLB wants to return, and has begun the process toward making that happen. If only this were as easy as getting ballplayers to stop spitting.