In April, Ubisoft announced the next installment in its never-ending Assassin’s Creed series, Assassin’s Creed Valhalla. Although the game’s marketing materials and trailer featured a male main character, Valhalla will give gamers the option of playing as either a male or female version of its Viking protagonist. A choice of playable protagonist isn’t a first for the franchise—Valhalla’s predecessor, Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey, also allowed players to select either a male or female main character—but whereas Odyssey expanded the series’ roleplaying elements, Valhalla seems set to double down on bloodshed. Ubisoft’s press release promised raids “more action-packed and brutal than anything Assassin’s Creed has seen before, thanks to a visceral new combat system that lets you bash, dismember, and decapitate your foes.”

Ubisoft seemed to anticipate some doubts about the historical accuracy of a ninth-century woman warrior kicking Anglo-Saxon ass. On the day the trailer debuted, the company published an interview with historian Thierry Noël, who worked on the game as a content adviser. Noël noted that while archeological sources are unclear on whether women served as warriors in Viking culture, Norse sagas and myths often featured fierce female characters and fighters. “It was part of their idea of the world, that women and men are equally formidable in battle,” Noël said.

It might seem surprising that Ubisoft would feel any pressure to justify the presence of a playable female character in Valhalla, regardless of her historical accuracy. Perfect veracity isn’t exactly Assassin’s Creed’s calling card; this is, after all, a series that centers on a virtual reality–genetic memory machine called the Animus; an ancient, highly advanced species called the Isu; and characters painlessly plummeting from tall towers into bales of hay. Even the series’ history-centric “Discovery Tour” mode lets players ride around on a unicorn—and not the historically accurate kind.

Less than two years ago, though, the announcement that World War II shooter Battlefield V would feature playable female characters prompted an uproar from an outspoken portion of players who protested the decision, often framing their objections on historical grounds. Battlefield developer EA DICE, which had already added a playable character from the Russian Women’s Battalion to a 2017 expansion to World War I shooter Battlefield 1, stood behind its decision and created a hashtag, #everyonesbattlefield, to counter the #NotMyBattlefield hashtag that some of the critics and misogynistic trolls had rallied around.

The Valhalla reveal hasn’t provoked a toxic internet tantrum. Yet the fresh memory of the Battlefield backlash, and Ubisoft’s apparent attempt to forestall a similar response, highlights how lopsided the gender makeup of playable characters in violent video games continues to be, and how sensitive a subset of gamers is to increasing inclusiveness in genres that have historically skewed toward male players and protagonists.

No video game genre has been more marinated in testosterone than the first-person shooter, the genre to which Battlefield belongs. The formative years of the modern first-person shooter, which began with the 1992 release of Wolfenstein 3D, were an adolescent-male playground, perhaps best embodied by the protagonist of 1996 shooter Duke Nukem 3D shoving wads of cash at stripper non-player characters and gruffly demanding, “Shake it, baby.” “Up to that point, female players had very few positive representations of their gender on screen and were almost always forced to assume a male gender when playing,” says David Owen, author of Player and Avatar.

But 20 years ago, the decade of Duke Nukem, Doomguy, and B.J. Blazkowicz—macho, musclebound, mostly silent FPS protagonists—gave way to a flowering of female-fronted first-person shooters. In a span of six months, from May to November 2000, a quartet of critically acclaimed shooters featured female main or playable characters: Perfect Dark, Medal of Honor: Underground, TimeSplitters, and The Operative: No One Lives Forever. In an era when shooters rarely even offered the option to frag as a female character, all four of those games shipped with women in their box art, and all except TimeSplitters made them the sole playable protagonist.

Considering the exclusionary discourse that still sometimes surrounds shooters today, it’s remarkable that leading ladies like Perfect Dark’s Joanna Dark, Medal of Honor’s Manon Batiste, and No One Lives Forever’s Cate Archer came to be. Yet it’s also perplexing that some of the forces that made those characters uncommon in 2000 have persisted so long after that landmark year.

“I’m fascinated by these games because I think that they represented a unique moment in games history,” says Cody Mejeur, a game scholar, developer, and activist. “They’re just a really interesting exception that proves the rule in a lot of ways. And they existed in this one moment in the development of FPS as a genre that we really haven’t seen since, and we really had to fight our way back to.”

In her 2014 book Gaming at the Edge, professor Adrienne Shaw summarized the two most common arguments for the importance of representation in media: the market logic argument (“People want to see people like them”) and the educational argument (“It is important that people see people unlike them in order to garner a broader view of the world”). Because electronic gaming matured after literature, film, and TV, one might have expected that the video game industry would’ve learned from and bypassed some of the struggles for inclusiveness that have marked other media. Instead, it fell prey to an even more virulent strain of the same plague.

“I think gaming is dramatically less welcoming to women in all aspects than any of those other media,” says Jennifer Malkowski, an assistant professor at Smith College and the coeditor of the book Gaming Representation. A few years before Gamergate laid bare the full extent of the antipathy toward women in the video game industry, Shaw identified the same issue, writing, “Despite the fact that digital games have developed alongside media representation critiques, numerous civil rights movements, and increased visibility of marginalized groups across popular media, it seems as though digital games are lagging.”

Carly Kocurek, an associate professor at Illinois Tech, recently looked back at gaming magazines from the mid-1990s and uncovered page after page of misogynistic marketing and messaging. “I love games so much that I’ve dedicated my career to studying them, and it was really weird and sad to revisit the media that had made me feel like I shouldn’t be involved,” Kocurek says. Even after women have broken into the industry, they’re sometimes targeted in ways that their male counterparts are not: Jade Raymond, who produced the original Assassin’s Creed, was repeatedly objectified and harassed after she publicly promoted the game on Ubisoft’s behalf.

We don’t have to look just like the characters we play to relate to them, but never seeing yourself on screen can be alienating.Carly Kocurek

According to Kocurek, women make up roughly 25 percent of the gaming industry’s workforce, but she says the percentage was less than half that a decade ago. In a 2010 paper, developer Robyn-Ann Potanin noted that just as players may be more likely to identify with characters who look like them, designers may be more likely to create characters who look like them. Thus, the lack of gender and racial diversity in the industry probably contributes to the lack of diversity in onscreen characters, which may reinforce the former in a vicious cycle.

“I think it makes a huge difference to players from marginalized backgrounds in the game industry to see some aspect of their identity reflected in playable characters,” Malkowski says, citing feedback from their female and trans students at Smith. “I routinely survey my students and say, ‘Does this matter to you? Do you buy games, or check out games, or have affection for games, based on whether you share a gender, or a race, or a sexuality with the characters?’ And routinely they say, ‘Yes, absolutely. This is super important to me.’” Although the majority of players tend to favor the male protagonist in games that allow either gender, such as Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey or the Mass Effect series, it’s often the female protagonist (like Mass Effect’s “FemShep”) who draws rave reviews, becomes canonical, or inspires the most enthusiastic fan campaigns.

It’s overly simplistic to say that representation is always important to the player; as Shaw explains at length in Gaming at the Edge, the role of representation depends on the player, the portrayal of the character, and the social context in which play takes place (i.e., online or offline), among many other factors. But a parade of Doomguys and Duke Nukems still tends to attract one type of audience and repel another. “We don’t have to look just like the characters we play to relate to them, but never seeing yourself on screen can be alienating,” Kocurek says. “If a game series, for example, never has women as meaningful characters, it’s implicitly saying, ‘This isn’t for you.’”

That sense of exclusion acts in opposition to gaming’s inherent interactivity, which heightens the player’s connection to the character. In a first-person shooter, the bond between player and character is, in one sense, the most intimate of all. “We’re never as aligned with a character in another type of media as we are with a game character, especially in a first-person shooter, where the conceit is that we’re literally seeing through that person’s eyes,” Malkowski says.

Yet seeing through the character’s eyes often prevents the player from actually seeing the character, apart from a floating arm attached to a gun. In theory, that might make it more feasible for designers to incorporate characters from more marginalized groups without raising the hackles of oversensitive dudes determined to protect their turf. “It’s especially easy not to have your fan base get upset about having to play as a woman if she doesn’t speak and you never see her,” Malkowski says, name-checking Chell, the rarely glimpsed, silent protagonist of Valve’s nonviolent Portal (2007) and Portal 2 (2011).

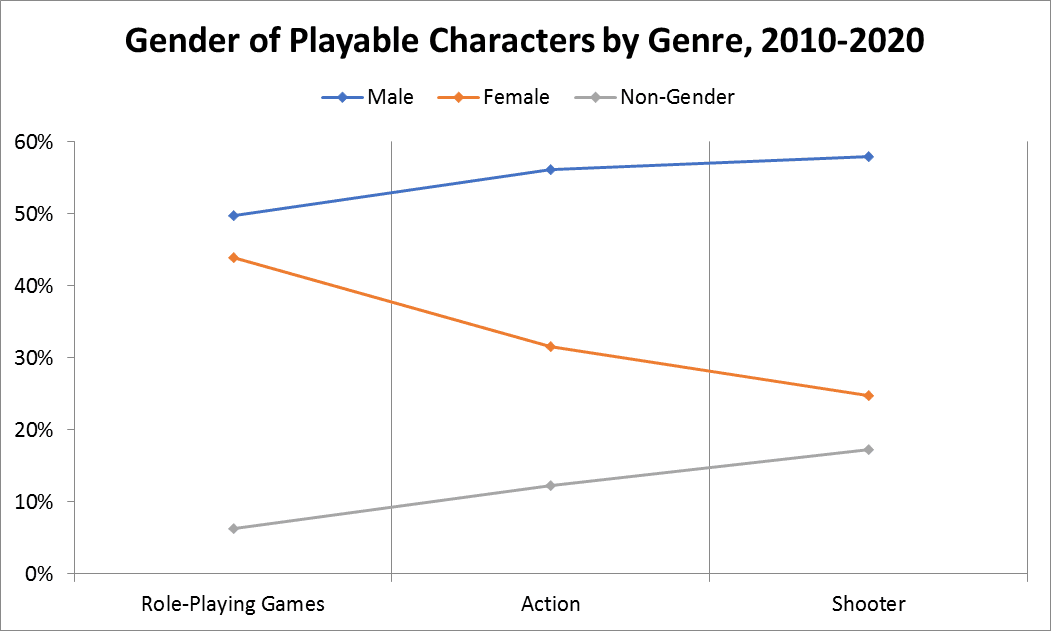

For most of the history of the first-person shooter, though, the capacity to disguise FPS protagonists hasn’t spawned (or respawned) more female characters. As Geoff King and Tanya Krzywinska noted in their 2006 book, Tomb Raiders and Space Invaders, “The first-person format is sufficiently open to accommodate players of any race or gender, but the white male is usually privileged by whatever markers of identity are supplied.” According to data provided by video game research firm EEDAR, an NPD Group Company, female protagonists in shooters and other violent video games are still far from the norm. The graph below shows the percentage of action games, shooters, and roleplaying games (the three most popular genres) from 2010 to the present that have included playable male, female, or non-gendered characters.

Although almost half (44 percent) of RPGs over the past decade featured a female playable character, fewer than a third (32 percent) of action games and only a quarter (25 percent) of shooters did. In shooters, non-gendered characters (such as some aliens or robots) were almost as common as female characters. Those modest figures are, if anything, inflated, because of an accounting quirk: EEDAR’s data doesn’t distinguish between single-player protagonists and optional, multiplayer-only characters, so shooters like Halo 3 and Call of Duty: Advanced Warfare and action games like Grand Theft Auto IV and V—all of which feature mandatory male protagonists in their single-player campaigns but also offer female multiplayer models—would receive the same designation as, say, EA DICE’s Star Wars Battlefront II, which offered only a female single-player protagonist, Iden Versio.

Although EEDAR’s data doesn’t go back further in reliable form, it’s certain that the gender skew was even more extreme decades ago. A survey of first-person shooters from 1991 through 2009, published by Macquarie University professor Michael Hitchens in 2011, found that 81 percent of FPS games over that span mandated a male avatar. Only 4 percent mandated a female avatar, and an additional 13 percent mandated male and female avatars or provided a choice of one or the other. No wonder, then, that Potanin, writing in 2010, concluded, “Video games are unique in their extreme gender disparity. No other media under-represents the female population to such a degree as games.” And FPS games were the worst culprits of all.

In the five years leading up to 2000, the protagonists of the bestselling shooters (according to NPD data) looked like the guests at a stag party.

Top Five Best-selling Shooters, 1995–99

Female FPS protagonists weren’t unheard of prior to 2000. Early shooters like Zero Tolerance (1994) and Rise of the Triad (1995) featured female playable characters, as did Unreal (1998), Star Wars Jedi Knight: Mysteries of the Sith (1998), Tom Clancy’s Rainbow Six, and multiplayer hits Starsiege: Tribes and Unreal Tournament (1999). However, only four pre-2000 shooters offered exclusively female protagonists, and three of them (Alien Trilogy, Trespasser, and The Wheel of Time) were book or movie tie-ins. Trespasser’s progressive credentials were undercut by the decision to replace the standard health bar with a heart-shaped tattoo on its protagonist’s ample polygonal bosom, which the player could leer at by looking down.

Considering that context, it’s a minor miracle that three original, female-protagonist-only shooters would come out in 2000 alone, and that Perfect Dark, an FPS featuring Carrington Institute espionage operative Joanna Dark, would become the year’s bestselling shooter. Twenty years later—and only three years short of the game’s 2023 setting—it retains the highest Metacritic score of any shooter on record.

Perfect Dark was primed for financial success because it was Rare’s spiritual sequel to GoldenEye 007, the 1997 blockbuster that topped the shooter sales charts for three years running. Upon its release, GoldenEye was widely hailed as the greatest console FPS and the best game based on a movie license. Its success earned Rare the opportunity to produce a sequel based on the next Bond film, 1999’s The World Is Not Enough, but the company turned it down. “Although we all really loved James Bond, we were pretty much sick of it,” says David Doak, a designer on GoldenEye and Perfect Dark. Doak and his colleagues thought they had done all they could with the Bond license, and the movie’s script restricted their storytelling. An original sci-fi scenario expanded the possibilities, and in the company’s quest to clear a path that diverged from 007’s, the protagonist’s gender, Doak says, was “another thing to change.”

When it came out, Perfect Dark was feted for its cutting-edge graphics and sound, its advanced enemy AI, and its customizable, endlessly replayable multiplayer modes. The choice of protagonist didn’t draw as much praise, but it was bold by late-’90s standards. “Before the game even had a title, I wanted to make a game starring a woman—in part because we’d just made a game which centered on a man, James Bond,” says Martin Hollis, who led GoldenEye’s development and steered Perfect Dark’s development until leaving Rare in late 1998. “I wanted a change, and for the sake of fairness I wanted the star to be a woman.”

When you’re making a game for people who love playing as Duke Nukem or space marines, how are they going to feel about getting flirted with by guys in a nightclub?Craig Hubbard

According to Doak, Joanna’s appearance was loosely modeled on Winona Ryder. He and Hollis mention a multitude of influences on her character, ranging from historical figures like Mata Hari and Joan of Arc to fictional figures like Dana Scully from The X-Files, Major from Ghost in the Shell, X-27 from Dishonored, and the titular characters of La Femme Nikita and Robert Heinlein’s Friday. The only video game character they cite as an influence on Joanna is Kim Kimberley, the protagonist of the first two installments of Silicon Dreams, a trilogy of text-based interactive fiction games developed by Level 9 computing in the mid-1980s. “Really the only effect that had was providing the realization, ‘Yes, it can be very cool to have a woman protagonist,’” Hollis says.

For many publishers in the late 1990s, a female FPS protagonist would have been a tough sell. Some of the skew toward male avatars in FPS games and other combat-oriented titles, Kocurek says, “has to do with who is imagined to be the player base. Some of it has to do with being risk-averse—the games like this that have made money mostly have male protagonists, and so to make money you should make a game with a male protagonist.” Although the Entertainment Software Association consistently reports a fairly even male-female split across the gaming audience as a whole, the ESA and other sources indicate that shooters are far more popular among men.

Neither Doak nor Hollis remembers any resistance to their project at Rare. “We were in a really lucky position, because we were allowed to make up what we wanted to do,” Doak says. Both Doak and Hollis had departed Rare by the time the game came out, but they weren’t aware at the time of any negative response to Joanna, although Hollis says he learned years later of a couple of critical letters.

Doak left Rare to form Free Radical Design, which chose PS2 launch title TimeSplitters as its first project. Like Perfect Dark, TimeSplitters was a sci-fi FPS, although its story played out over nine loosely related levels with settings scattered over a century. Each mission allowed players to select either a male or female playable character, with the 18 campaign characters making up a minority of the 64 playable characters available in the game’s multiplayer modes—a total that nearly doubled in TimeSplitters 2 and TimeSplitters Future Perfect, the third and final game in the series (so far).

Making multiple protagonists for each mission doubled the character design work, which would have made it easy for Free Radical to limit player choice by focusing on one gender. (A similar calculation helped fuel the rise of one of gaming’s most iconic female characters: 1996 smash Tomb Raider morphed from a game with a male-only protagonist to one with a choice of male and female characters before workload concerns forced Core Design to focus on the female Lara Croft.) But a limited array of characters would have conflicted with Free Radical’s mission statement for TimeSplitters, which Doak says was “to make a game which had something for everyone.” The studio wanted TimeSplitters’ wide assortment of settings and customizable maps to be matched by its character roster. “I’m fiercely proud of what we did with TimeSplitters in terms of having some diversity in gender and diversity in race in the characters,” Doak says.

Doak encountered more resistance to diversity with TimeSplitters than he had at Rare. TimeSplitters was published by Eidos Interactive, which had previously published the hugely successful Tomb Raider. Yet Tomb Raider was an action-adventure game, and a shooter was viewed as a different beast. While Eidos U.K. was accommodating, Eidos U.S. required some cajoling. “It was, ‘Oh, we can’t sell a shooter if it doesn’t have a guy on the box,’” Doak says. “That was the reflexive answer you got to stuff stateside.” The sequels to TimeSplitters featured one campaign character, male space marine Sergeant Cortez, although TimeSplitters 2 allowed players to control Cortez’s female sidekick Corporal Hart in co-op mode.

Like Joanna Dark, No One Lives Forever’s Cate Archer, a 1960s covert operative for a counter-terrorism organization called UNITY, emerged as an alternative to James Bond. Whereas Perfect Dark was designed with a female protagonist in mind, NOLF’s original main character was a man named Adam Church. “He was conceived as the guy you call when the 007s of the world can’t get the job done,” lead designer Craig Hubbard recalls. Church was still slated to star when developer Monolith announced NOLF at E3 in 1999, only 17 months before the game was released. But the fledgling title sparked so many Bond comps that Bond distributor MGM got wind of the game and sent a cease and desist.

As a result, Hubbard says, “We started experimenting with how to avoid being sued out of existence. We tried a few variations, but I was having a hard time letting go of a sample scene I’d written where the hero is flirting with a female contact and she’s not having it. I’d been having a lot of fun subverting Bond tropes, especially regarding male-female relations. Then one day it occurred to me that it was the contact who actually owned that scene and that she could be the solution.”

Although the character concept arose more out of necessity than by choice, the protagonist swap gave the story a subtext that made it more meaningful. Cate is an ex–cat burglar who’s given a chance only because half of UNITY’s male agents have been wiped out. Her efforts to prove herself in a male-dominated field mirror NOLF’s struggle to stand out in a male-dominated genre. “You’re the first female operative UNITY has ever employed,” Cate’s mentor tells her in the game’s first cutscene. “The committee is old-fashioned. They need time to get used to the idea of a woman in this line of work.”

Cate’s gender drove some cosmetic (and kind of cringey) design decisions, including the addition of items like lipstick explosives, sleeping gas perfume bottles, and lockpick barrettes. But placing her in a 1960s setting allowed the game to expose and poke fun at the biases of the enemies and allies who fixate on her femininity. “One of the reasons I love that narrative is you’re playing as a woman agent who is basically constantly being sabotaged by the men who are around you, either the men in your agency or the men that you’re fighting,” Mejeur says. “And despite all of their efforts to shut you down, you basically thumb your nose at them and end up coming out on top.” In one memorable exchange, Cate rescues a sexist scientist who’s aghast at UNITY’s choice of agent. “They sent a woman to liberate me?” he asks. The cutscene stops as the player-controlled Cate mows down four male guards. “As I was saying,” she calmly continues when the cutscene resumes, “perhaps we should go.”

Cate’s characterization, Hubbard says, “was definitely a bit scary considering the target audience. We discussed it at length. It wasn’t simply her being a female player character, as that can be handled very superficially, but also the fact that I wanted her to be an actual woman. When you’re making a game for people who love playing as Duke Nukem or space marines, how are they going to feel about getting flirted with by guys in a nightclub?”

Hubbard wasn’t aware of any organized resistance to NOLF’s mid-development gender change. “That was still the print era,” he says. “It was a lot harder to mount a viable backlash campaign in the days before social media, YouTube, Reddit, etc.” But he found out firsthand that a female protagonist could suppress sales. “After the game shipped, I did happen to be in a game store when a customer came in to return his copy because he didn’t realize he’d have to play as a woman,” he says. “I’m not making that up. I asked the clerk if she had experienced that before, and she said once or twice.”

NOLF won awards from multiple gaming publications, and both the original and its 2002 sequel boast 91 ratings on Metacritic. But NOLF 2 still hasn’t received a sequel or reboot, and not solely because the franchise is stuck in copyright hell. “The NOLF games didn’t sell as well as we hoped,” Hubbard says. “Some research was done and the clear conclusion was that the issue lay with the major pillars of the series: female protagonist for a first-person game, humor, the ’60s setting, and stealth.” Instead of starting NOLF 3, Hubbard began working on F.E.A.R., the 2005 survival horror shooter, which featured a male protagonist, Point Man. An in-progress expansion for NOLF 2 was repurposed into a poorly received (and more action-oriented) prequel, Contract J.A.C.K., which starred male contract killer John Jack.

Medal of Honor: Underground, which starred French resistance agent Manon Batiste, didn’t deal as explicitly with feminist themes. “It wasn’t from a female or a male perspective ever, really,” recalls producer Scott Langteau. “It was always from a soldier’s perspective.” But given that much of popular culture—and a long line of World War II shooters beginning with Wolfenstein 3D—had conditioned players to expect male protagonists of WWII tales, Underground still subverted norms.

In the Medal of Honor series’ 1999 debut, Manon was an NPC who explained game mechanics and offered encouragement and assistance to protagonist Jimmy Patterson. The Resistance played a key part in the plot of the first game, and because players were familiar with Manon, “it seemed like an absolute natural thing to highlight her as the protagonist for the next game and to do a much deeper dive into that Resistance story and flesh out her character,” says Peter Hirschmann, who produced the original Medal of Honor. Hirschmann remembers self-doubt being a bigger obstacle to that plan than external opposition, but Langteau says some of the suits at publisher Electronic Arts balked at the idea of elevating Manon to the lead role.

“It was tough,” he says. “Our executives were not for it. We had to really kick and scream and fight and say that, no, this is a great story. There’s a lot of great material here. She’s a great character. This’ll be a good departure from what people expect.” It helped that Medal of Honor had been a big hit and that Manon was not a new character, but Langteau didn’t take any chances. “We just went in and said, ‘This is what we want to do and we don’t have any other ideas,’” he says. “Basically, leaving them with the no option but to say, ‘OK, let’s see where this goes.’”

Manon was an amalgamation of many of the real-life women who served as spies and resistance fighters during World War II, including Hélène Deschamps Adams, who consulted on Underground. Hirschmann says that “shining a light and getting some additional representation in there for what actually wins the war effort was part of the motivation” for focusing on Manon in the series’ second game. Langteau adds that his own identity as one of the first gay producers of a major game franchise was “another reason why I would have been open to, ‘It should be about anybody. It shouldn’t be just this big straight white macho guy. There are other people who sacrificed and lost their lives and who were in peril.’”

In August 2000, two months after Joanna Dark had graced the cover of GamePro, Manon made the cover too, accompanied by Regina from Dino Crisis 2. Although it didn’t launch until late October, Underground was the 10th-best-selling FPS of 2000 and compiled an 86 score on Metacritic. Just as precious as the critics’ compliments were the letters Dreamworks received from players who appreciated Manon’s starring role. “We heard from many women who just were so thankful and loved the game,” Langteau says.

The confluence of female FPS characters in 2000 had a special significance for Mejeur. “I hadn’t become aware of the fact that I was trans by the time I was playing these games, and I was really drawn to these games that had women protagonists because they were so different from everything else that I played, that I saw, that I saw in my male friends who were playing games,” Mejeur says. “And it gave me a space where I could see, yeah, you can be a powerful woman character who can go on and save the world.”

Mejeur acknowledges that many male players “didn’t come out of them with any particular new ideas about gender.” Although many men choose to play as women when games give them the option, they have varied reasons for doing so. Doak says he’s always played as women because, “I just enjoy that part of the roleplaying.” Others may opt for female characters because they’re typically less bulky and therefore potentially harder to hit. Some do it for voyeuristic reasons; the internet abounds with tutorials devoted to creating “attractive” female characters. “A lot of men, when they’re interviewed, will say things like, ‘Oh, when I use female avatars, I just want to do it because they’re hot,’” says Georgetown University assistant professor Amanda Phillips, author of the newly released Gamer Trouble.

Early incarnations of Lara Croft encouraged that kind of attention. Although Lara was a highly capable character—“She confounds all the sexist clichés apart from the fact that she’s got an unbelievable figure,” designer Toby Gard once said—her exaggerated proportions turned her into a sex symbol and monopolized much of the discourse surrounding the series. (For the first Tomb Raider film, Angelina Jolie wore a padded bra so as not to detract from what the actress called Croft’s “trademarks.”) Later installments in the series made Lara less voluptuous and less scantily clad, and the franchise’s marketing adopted a less sexualized tone.

The female-fronted first-person shooters of 2000 weren’t conducive to the same sort of ogling. Malkowski says, “There was something bold, I think, about creating these games that you had to play as a woman, but you couldn’t objectify her in the same way that you could in Tomb Raider if you wanted to play that way.”

That’s not to say that the female-led shooters of 2000 were totally immune to Tomb Raider or Trespasser-style titillation, especially in their marketing materials. Manon Batiste’s appearance was based on the wife of Medal of Honor art director Matt Hall, but No One Lives Forever publisher Fox Interactive conducted a movie-style casting search to find the face and frame of Cate Archer. In a press release announcing the selection of actress and model Mitzi Martin, the publisher promised that the game would deliver “style and sexiness.” Hubbard says, “We absolutely didn’t want to objectify her, but we also didn’t want to masculinize her. The premise was that she doesn’t want to give up being a woman in order to be treated fairly.”

Cate didn’t don any outfits Felicity Shagwell wouldn’t have worn. Even her skintight attire was tame compared to a TV ad for Perfect Dark, in which a naked Dark, played by model Michele Merkin, gets dressed while a male voice-over says, “Meet special agent Joanna Dark in Perfect Dark, where you’ll find out that the only person man enough to handle a job like this … is a woman.”

The game itself, though, catered far less to prurient interests. “I think the game is better off without this kind of adolescent boy’s idea of femininity,” Hollis says, adding that “the core of Joanna Dark was the idea that she was not a sexual object, or a sex symbol, but that she was an extremely competent spy who might have been your older sister.” Doak says that part of the motivation for making Joanna a “very practical and not sexualized character” was an “internal rebellion against the rest of Rare,” which had produced salacious characters like Killer Instinct’s Orchid.

Doak and Hollis are critical of the character’s redesign for 2005 sequel Perfect Dark Zero, which Doak says “got pulled more towards the stereotype” of a so-called cyberbabe. “I think it was the wrong way to take it,” Doak says. “That’s a bit depressing, really.” To promote the sequel, Joanna appeared on the cover of a one-off gamer edition of FHM, provocatively unzipping her jumpsuit above a headline that blared, “Step aside God. The perfect woman—as created by man!”

In retrospect, Doak says, some of TimeSplitters’ female characters played into male fantasies in a way that “has dated quite badly.” Doak adds, though, that “As much as there are sexualized and scantily clad female characters in the TimeSplitters games, there are also very, very realistic military female characters, which basically are wearing the same kind of gear as the male guys. It’s not like it was Dead or Alive [Xtreme] Beach Volleyball.”

There are two ways in which Joanna, Manon, and Cate conform to convention. For one, they’re white, like Lara Croft—who was called Laura Cruz until Eidos demanded a more “U.K.-friendly” name. In his review of FPS games from 1991 to 2009, Hitchens found that 75 percent of the titles whose avatars’ races could be determined enforced exclusively Caucasian characters. Although TimeSplitters offered an African American female character and Turok 3’s Danielle Fireseed was Native American, female-fronted FPS games were racially homogenous: Of the 20 titles Hitchens identified with mandatory female protagonists, only Portal and Mirror’s Edge (2008) featured non-Caucasian playable characters. As Shaw wrote in Gaming at the Edge, “Representations of people of color in games are often discussed separately from gender, meaning that much of the discourse about female representation in games implies white, female characters.”

Second, although those three characters are all very capable of killing, they’re also all either spies or covert agents who operate in a somewhat stealthy manner. “If you think about gender stereotyping, of course women would be the ones to be the spies in a first-person game rather than the heavies,” Malkowski says. That gendered stealth-combat dichotomy recurs in more modern shooters with dual protagonists, as exemplified by Booker and Elizabeth in BioShock Infinite: Burial at Sea or Corvo and Emily in Dishonored 2.

The “more pernicious and sexist side” of that trend, Mejeur says, is that it reinforces conceptions of women as duplicitous or unsuited for the front lines, restricting female characters to what Phillips describes as “socially acceptable ways that women can be powerful.” As evidenced by more modern shooters like Overwatch, Apex Legends, the Borderlands games, and Gears 5, Phillips says, “the ways that we’re able to express gender have become a lot more flexible,” and for her, “to see these new women who are bulky and muscular and doing all the manly, beefy things is really affirming.”

As Phillips points out, though, when people equate strong female characters with hulking women who wield guns as big as the guys’, “what they’re essentially asking for is for women to kind of ascend to this place of manhood,” which is “perhaps not in the spirit of what a lot of feminists are asking for.” It’s also emblematic of a one-note understanding of masculinity. The most encouraging characters may incorporate aspects of violent and nonviolent protagonists. As the meme asks, why not both?

“For me, a strong character is someone like Kait [Diaz],” says Gears franchise narrative director Bonnie Jean Mah, referring to the series’ first female playable protagonist. “She’s vulnerable, she’s brave, she does whatever it takes to help the people that she loves. And sometimes that means that she is picking up the Lancer and she’s taking out the enemy and being that violent kickass character, but she also has the other sides to her personality that make her a well-rounded character. And that’s what I love about our industry, is that type of portrayal coming much more to the fore.”

Why was 2000 the year of equal opportunity FPS protagonists? Although she was more of a puzzle solver than a fighter, the Lara Croft precedent was probably partly responsible. “You can imagine the meetings where people are saying, ‘We want to have a female character,’” Doak says. “And you can’t say, ‘Well, that’ll never work because it never works.’ Because people say, ‘Well, actually, Lara Croft.’ It’s the counterexample that opens the door.”

The 1990s girl game movement may be another precursor. Although “girl games” trafficked in traditionally feminine interests, implying that women wouldn’t want to chainsaw their way through the hordes of hell, they did, at least, invite them into what had been a boys’ club. Kocurek, who wrote a book about one of the movement’s formative figures, says, “It’s really an effort to intervene and change the story about who games are for. That happens in the mid-1990s, and while some of those companies are short lived, you get a lot of evidence that, wow, girls will play games. Women are interested in games. That was not necessarily believed to be true at the time.”

Lastly, certain series—and the first-person shooter genre as a whole—were sorely in need of variety. “I suppose people just wanted to do something different,” Hubbard says. By 2000, Duke Nukem–esque characters had become a cliché that would be parodied the following year by Serious Sam: The First Encounter and its intentionally stereotypical protagonist, Sam “Serious” Stone.

It gave me a space where I could see, yeah, you can be a powerful woman character who can go on and save the world.Cody Mejeur

Although 2000 was a watershed year, it didn’t set off a flood of female protagonists. If anything, it provided a glimpse of a gaming landscape that wouldn’t return for 15 years. “That was one of those moments where we could go to the good place or the bad place, and we clearly went to the bad place,” Mejeur says.

Hitchens logged seven FPS games from 2000 in which it was possible to play as a female character, compared to nine male-only titles. That was the smallest gap since Doom debuted, but the numbers diverged from there. “After 2000 there is a noticeable shift, with male avatars increasingly predominating,” wrote Hitchens, who also observed that after 2000, the genre increasingly gravitated toward historical-warfare settings that were less likely to feature female protagonists (notwithstanding the Metroid Prime trilogy). For the rest of the decade, no year featured more than two female-protagonist-only shooters on non-handheld platforms.

In hindsight, Mejeur says, 2000 looks like a moment “that was really ripe for these games to exist. And then the way they developed after that, especially with FPS going more and more toward being a war-shooter genre, it disappeared very quickly. And we’ve only just started to see it come back, really since prominent discussions of representation started before and after Gamergate.” Nowadays, playable female protagonists pop up in formerly macho franchises, from Gears to Call of Duty: Black Ops III (which didn’t do a great job of gender-neutralizing its campaign mode but did feature female enemies and Cara Delevingne as a gamer in its trailer) and the rebooted Call of Duty: Modern Warfare to the latest offshoot of Wolfenstein 3D, Wolfenstein: Youngblood (which may not be a good game, but still seems like a sign of the times).

What’s more, whereas the non-voice-acting creators of Joanna, Cate, and Manon were all men—as was the original TimeSplitters team—women are playing integral roles in shaping contemporary characters. Manon will be back in the upcoming Medal of Honor: Above and Beyond, but this time, Hirschmann says, women make up almost half the writers’ room.

“We have more diverse games now than we had in 2000, for sure,” Mejeur says. “But there’s a lot of work to be done there, too. And maybe looking back at these games can help with that.”

Thanks to Mat Piscatella of the NPD Group for research assistance.