On Sunday night’s installment of The Last Dance, the ESPN docuseries about the rise of the Chicago Bulls, Michael Jordan retired from basketball to try his hand at baseball. It was an astonishing story back in 1994—Jordan leaving the NBA at the top of his game to pursue an MLB pipe dream—but it seems even more bonkers in retrospect. At that point in time, two-sport stars were relatively commonplace: Bo Jackson was in his final MLB season, while not one, but two former Atlanta Falcons defensive backs (Brian Jordan and Deion Sanders) were patrolling National League outfields.

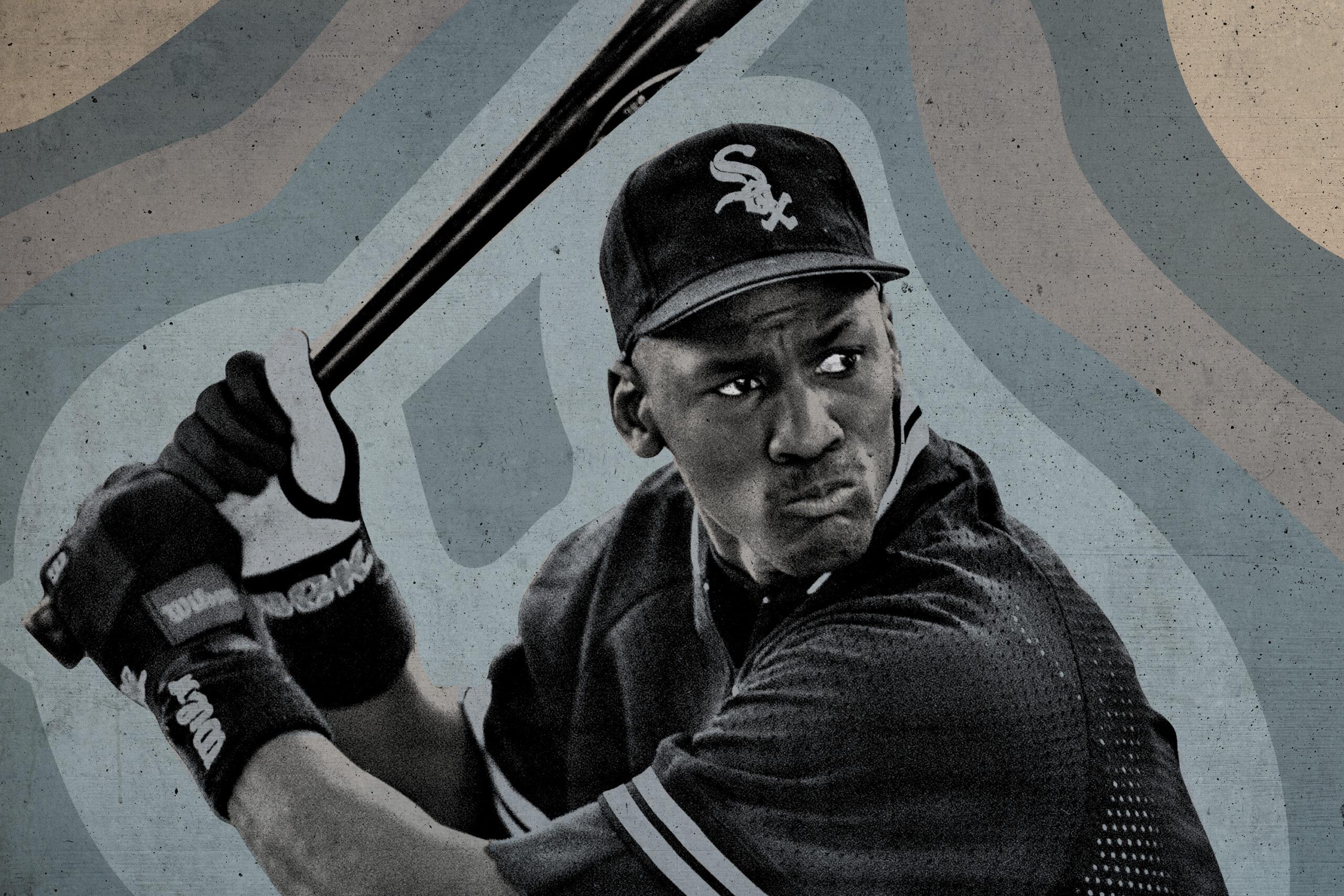

By those standards, it looked downright risible for Jordan to hit just .202/.289/.266 with 114 strikeouts in 497 plate appearances in his sole Double-A season. (He was also hit by four pitches, which, imagine being some anonymous minor league kid with no fastball command and plunking Michael Fucking Jordan. Yikes.) Even though Jordan stole 30 bases, his success rate was just 62.5 percent, well below the accepted break-even point of 70 percent. In a vacuum, Jordan was a very, very bad ballplayer. But take into account his history with the game (or lack thereof) and a few other factors, and it starts to look like a minor miracle that he was even as good as he was.

They say that the hardest thing to do in sports is hit a baseball. (Well, Ted Williams says that, so maybe we should account for some bias.) But that applies to people who weren’t jumping into the sport at age 31 after not having played competitively since high school. Learning to hit a baseball at a big league level is a lifelong process, one that can be derailed by even a momentary layoff. Rangers infielder Jurickson Profar was the no. 1 prospect in baseball heading into 2013, but after injuries wiped out his next two seasons’ worth of reps, he’s become a journeyman bench bat. Current Cardinals QB Kyler Murray was one of the most coveted high school infielders in the nation in 2015. But after skipping the 2016 season, he went 6-for-49 with no extra-base hits and 20 strikeouts at the University of Oklahoma in 2017. That he turned himself into a top-10 MLB pick the following year is a remarkable feat considering the layoff.

Jordan was nowhere near that level of high school baseball prospect, and by the time he arrived in White Sox camp, he hadn’t played a competitive baseball game in almost 15 years. He showed up having had a crash course in a skill that can’t be mastered without consistent practice over long stretches of time. And he was thrust back into the game at a difficult level.

Double-A is minor league baseball’s weed-out course. Most pitchers in the low minors have either a good fastball or a good breaking ball, but not both, and those who do have good raw stuff are still figuring out how to throw strikes. If a hitter with a pretty swing and good hand-eye coordination is going to struggle with off-speed pitches, Double-A is usually where we find that out. (Tim Tebow, who has a Forrest Gumpian propensity for inserting himself into sports debates, hit .273/.336/.399 at Double-A, but only after a season and a half at lower levels.)

Even for players with lots of baseball experience, seeing a big-league-quality curveball for the first time is a lot like seeing an alien. And Jordan was no exception. His 22.9 percent strikeout rate doesn’t look that bad by modern standards, but the numbers don’t tell the whole story: He struck out that much despite hitting for no power with a swing that could euphemistically be described as “contact-oriented.” Moreover, the strikeout rate in 1994 was only about two-thirds what it is today. Jordan’s strikeout rate would have been among the 13 highest in MLB in 1994.

Jordan did manage to walk a lot considering his utter lack of power (51 times in 497 plate appearances) and hang the bat out there enough to hit .202 on mostly slapped singles and hustle doubles. That indicates that, in addition to having good hand-eye coordination, Jordan had at least some sense of the strike zone. Even if the physical mechanics of hitting let him down sometimes, he wasn’t just going up there and flailing like a frat boy in a dizzy bat race.

Which brings up the other thing Jordan had going against him: his body.

We’ve probably seen the last NFL/MLB crossover star, but it’s still positively commonplace to see exceptional athletes play both baseball and football. Murray is the most obvious example, though the top pick in the 2019 MLB draft, Adley Rutschman, moonlighted on the football team at Oregon State. The year after Auburn lost Bo Jackson to the NFL, Frank Thomas got to campus and played football as well as baseball. At one point, the Colorado Rockies had both Peyton and Eli Manning’s college backups on their roster—and there are hundreds of other examples.

But the physical demands of baseball and basketball are so different that it’s extremely difficult to play both at a high level. Basketball players, to paraphrase Jay Bilas, tend to have length. Long arms and legs take up space on defense and make it easier to shoot over opponents or reach the basket on dunks. When it comes to baseball, though, long limbs are really beneficial only for pitchers, who turn that extra distance between the shoulder and the hand into increased angular momentum—in other words, fastball velocity. That’s why the overwhelming majority of baseball-basketball crossovers are pitchers. Mark Hendrickson played in both the NBA and MLB, and Jordan’s Chicago Bulls teammate Scott Burrell was once a first-round pick of the Seattle Mariners. Milwaukee Bucks wing Pat Connaughton was a highly regarded pitcher at Notre Dame and a solid prospect in the Orioles system before he chose to play basketball full time. Hall of Fame pitchers Robin Roberts, Sandy Koufax, Bob Gibson, and Ferguson Jenkins all played high-level college or pro basketball, while basketball Hall of Famer Dave DeBusschere played for the White Sox in parts of two seasons.

For a position player, on the other hand, having long limbs carries all the mechanical complexity taller pitchers experience with very few of the benefits. Great hitters tend to be compact, generating bat speed and power with relatively short swings. Even the great hitters whom we think of as big guys usually strike out a lot, top out at about 6-foot-4, and have shorter limbs than Jordan.

At 6-foot-2, Babe Ruth was extremely tall for his era, but nobody has ever described him as “long.” Willie Mays and Mickey Mantle were both under 6-foot with broad shoulders and stubby limbs. Albert Pujols is a big, imposing figure and could squat an actual bull, but he’s also proportioned like a Duplo man and is three inches shorter than Jordan anyway. Giancarlo Stanton and Aaron Judge are both Jordan’s height or taller, but also made mostly out of torso—and both strike out 200 times a year.

Jordan was listed at 6-foot-6 and 205 pounds on the Double-A roster. It’s not literally impossible to become a big league outfielder at that size, but it’s close. In all of MLB history, only two position players listed at 6-foot-6 or taller have hit .300 in a season: José Martínez in 2018 and Dave Winfield—who’s one of the greatest all-around athletes of the 20th century—four times. Among position players listed at 6-foot-6 or taller and 205 pounds or less, only one, Darryl Strawberry, has a positive career-wins-above-average in a career of 500 games or more.

That’s why, even though you can’t take five steps in an MLB clubhouse without seeing someone who played college football, there are only a handful of position players who played high-level basketball. Tony Gwynn and Kenny Lofton—both smaller, stocky outfielders—played point guard in college. Hall of Fame shortstop Lou Boudreau and five-time All-Star Dick Groat were All-American basketball players at Illinois and Duke, respectively, but both played at a time when basketball had barely become organized. The most recent NBA-MLB crossover among nonpitchers is Danny Ainge, who played three seasons for the Blue Jays. A 6-foot-4 second baseman, Ainge hit .220/.264/.269 with 128 strikeouts in 721 plate appearances. Just like Jordan, that’s a lot of strikeouts for a player who hit for so little power.

Watching Jordan at the plate makes it easy to appreciate why it’s so hard to hit with his body type. His swing is not only long, but disjointed. The former makes it hard for him to hold off on breaking pitches or catch up to elite velocity, while the latter takes all the power out of his bat. You’d expect Jordan, being such a big, strong guy, to be able to hit the ball hard, but he’s not leveraging that strength the way a trained hitter would.

Mike Trout, on the other hand, has a short swing that maximizes the time the barrel spends in the zone. He generates power from his legs by driving off of his back foot in concert not just with his arms, but the twist in his torso. Compare his swing to Pujols or Barry Bonds and you’ll find subtle differences but the same economy of motion—and above all, a coordinated weight transfer.

Looking at Jordan’s swing, the very first thing that jumps out is how uncoordinated his weight transfer is. He looks hesitant, committing only partially to the swing and halting his forward momentum to the point where he sometimes knocks his knees together. He looks like a pitcher, or a baby deer.

So why does Terry Francona, who by some hilarious historical fluke served as Jordan’s manager in 1994, say that with another 1,000 at-bats Jordan could have made it in the big leagues?

Well, despite all those disadvantages, and despite having a swing that looks like Charles Barkley swatting at a mosquito with a five-iron, Jordan still went into Double-A cold and hit .202. By the time he got to the Arizona Fall League that year, he was starting to blend in and look more comfortable. The problems Jordan faced were technique-based, bad habits that could at least theoretically be trained out of him. And whatever his other faults, if any athlete could learn to hit a baseball through sheer brute force of training, Jordan probably could. If the wrong up-and-coming small forward had bet Jordan $50,000 during a golf game that he couldn’t crack the White Sox roster by Opening Day 1996, who knows what would have happened?