Adam Horovitz, a.k.a. Ad-Rock, a.k.a. one-third of the beloved NYC rap trio Beastie Boys, is back where he belongs: onstage, performing the group’s classic song “Girls.” Yes! “Girls”! Everyone loves “Girls”! You know “Girls,” off their smash debut LP, 1986’s License to Ill. Vibrant, irreverent, ramshackle, hilarious in context, boorish in the extreme, stupid as all hell. The stupidity, at least, holds up. Which is to say that along with performing “Girls,” Horovitz is now performing his profound chagrin that the song “Girls” even exists.

Girls

To do the dishes

It’s 2019. He is holding court at the Kings Theatre in Brooklyn, an affable titan on the softer side of 50, hair defiantly gray, clothes defiantly dadcore, rocking the mic though his rapping days are pretty much behind him. Instead, he recites these lyrics in an exasperated, apologetic, Thank you for ignoring my Ted Talk deadpan.

Girls

To clean up my room

The song was “supposed to be this, like, stupid and ironic joke, but understandably it wasn’t that funny,” he’d explained by way of introduction, though the nostalgia-drunk capacity crowd is still chuckling a little. But now, with Horovitz’s tacit encouragement, they’re laughing at him, not with him.

Girls

To do my laundry

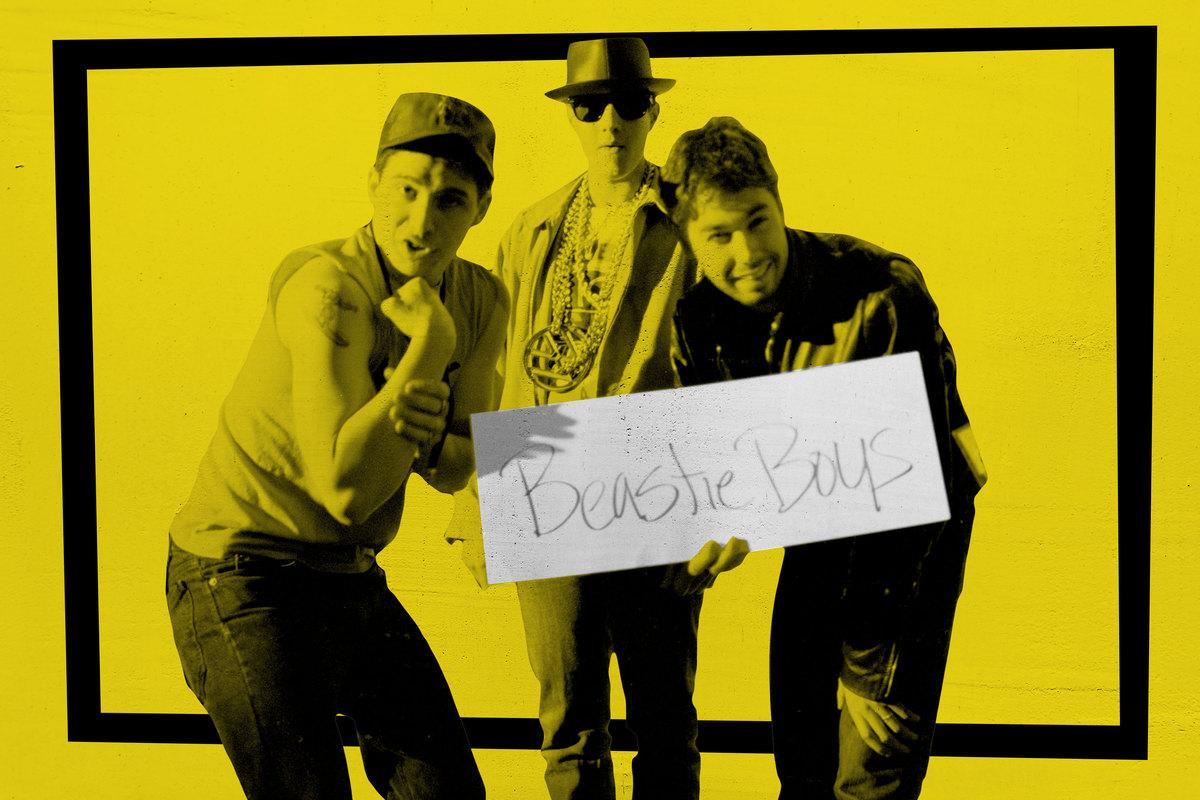

We’re about halfway through Beastie Boys Story, the new “live documentary” directed by Spike Jonze, starring Horovitz and his fellow surviving bandmate Michael “Mike D” Diamond, and premiering Friday on Apple TV+. (The third Beastie Boy, Adam “MCA” Yauch, died of cancer in 2012.) It’s a feature-length staging of a career retrospective the fellas briefly toured as a companion piece to their luxe 2018 autobiography Beastie Boys Book. The book is way deeper and better, as thought-provoking nostalgia exercises go, but it also retails for $50 and is fully bible-sized to the point where the binding starts to crack if you even glance at it. Plus there’s no substitute for looking Horovitz in the eyes, more or less, as he reckons with the more knuckleheaded aspects of his past.

Girls

And in the bathroom

Girls

Pause. Heavy sigh. Applause break. “So we didn’t know what was a joke and what wasn’t a joke at that time,” he concludes. “I mean, shit got really blurry.”

Beastie Boys Story revels in various blurs, starting with the vivid dystopia of ’80s New York City, where the teenaged fellas first convened as a hardcore band. “I met Yauch and Mike and [early member] John Berry at a Misfits show in 1982,” Horovitz tells us. “It might’ve been Circle Jerks, but I like the Misfits more, so I’m gonna say that it was at a Misfits show.” That’s the last time he cops to revising history so as to look cooler, or smarter, or more enlightened.

That history, even before the giant (and delightful!) Beastie Boys Book, was well established even among casual fans. The group quickly shifts from hardcore to hip-hop. (The movie’s first great moment is TV footage of an underage Horovitz, lurking in a minor-talk-show crowd, asking one of his heroes, the DJ pioneer Afrika Bambaataa, if he’s ever heard the early Beasties prank-call single “Cookie Puss.” Bambaataa says that he has, and describes it as both “tough” and “funky” as Horovitz’s face lights up like a bodega Christmas tree.) The group meets evil-genius producer Rick Rubin and evil-genius rap-biz titan Russell Simmons, who together sign the Beasties to Def Jam Records and goad the boys into kicking out early drummer Kate Schellenbach and rebranding as brotastic pro-wrestling heels. Cue the rap-rock provocations of License to Ill, as typified by both “Girls” and “(You Gotta) Fight for Your Right (to Party),” an enormous hit and a lifelong albatross.

The movie’s second great moment concerns the Beastie Boys’ infamous early gig opening for Madonna. Again, Horovitz channels his younger and substantially dumber self, half-yelling as he recreates his stage banter at that particular time:

I’m the king Ad-Rock and I’m the fuckin’ king of the Kings Theater! And we’re the Beastie Boys, and we’re here tonight to crush all competition! After we leave tonight, you can burn this motherfuckin’ place down! ’Cause y’all motherfuckers ain’t shit!

“Just keep in mind,” Diamond interjects, “that this is who Adam was cursing out.” The giant screen behind them flashes to a vintage photo of beaming preteen girls, thrilled just to be seeing Madonna. Huge laugh break—everyone’s laughing this time.

Yes, License to Ill made the Beasties famous; yes, they quickly came to despise the culture that album both lampooned and further inspired. “We definitely didn’t think that the party-bro frat dudes that we were making fun of were gonna come,” Diamond says of the trio’s first blockbuster national headlining tour, whose stage props included, as you might recall, a giant hydraulic penis. “But turns out that they loved ‘Fight for Your Right (to Party).’ And, you know what? We liked being loved. So fuck it. ‘Pass me a 40, let’s get fucked up.’”

So the Beasties burn out, slowly but severely. “We missed being the people we used to be,” Horovitz explains, further lamenting their early stage props. “All the dumb shit we were saying, and the go-go cage, and the fuckin’ beer, and the dick in the box, and the whole thing was just getting fucking embarrassing.”

They break painfully from Def Jam, reconvene in L.A., rediscover their true selves, slowly craft their sample-packed 1989 classic Paul’s Boutique, wince when nobody buys it, soldier on, regain their commercial momentum with various subsequent jams including 1994’s mighty “Sabotage,” triumphantly tour America as their actual non-frat-bro selves this time, and endure as genre-blending elder statesmen right up until their headlining gig at Bonnaroo 2009, which they don’t realize in the moment is their last show together, before Yauch’s cancer diagnosis changes everything. None of this is new information; none of it is unwelcome territory to revisit.

Love these guys. I’ll hang out with these guys anytime. The two living Beastie Boys awkwardly high-five twice during this movie, the second time after Diamond references the early-’80s TV show Hart to Hart. They’ve got the intimate home videos, the goofy Soul Train footage of Diamond close-talking Don Cornelius, the ludicrous fashion choices throughout. Let’s just say that nobody in the ’90s better channeled the utter outlandishness of the ’70s.

What Beastie Boys Story doesn’t have is much of the high-concept whimsy you’d rightly expect from Spike Jonze, director, of course, of the band’s career-remaking “Sabotage” video. At one point they wheel onstage a re-creation of the reel-to-reel tape machine Yauch used to loop Led Zeppelin’s “When the Levee Breaks” into “Rhymin’ and Stealin’,” a License to Ill jam that has aged a little better. (Relatively.) Horovitz and Diamond occasionally misread the teleprompters, or the teleprompters fail them, or Jonze fails to deploy a goofy “CRAZY SHIT!” drop at the exact right moment. (It’s Bill Hader’s voice, apparently.) From the outtakes tacked on at the very end, I gather the shows had a running bit where a celebrity would emerge from the crowd to further elucidate the commercial failure of Paul’s Boutique. (Steve Buscemi: “When the tree fell in the forest, nobody heard that shit.”) But what you mostly get is two hypercharismatic 50-somethings telling stories, mocking old outfits, and making various apologies.

Those apologies hit a little harder in the book, but it’s still bracing now when Ad-Rock ruminates on the era when the Beastie Boys weren’t all boys: “It was decided at some point that we had to kick Kate out of the band, because she didn’t fit into our new Tough Rapper Guy identity,” he says. “Now how fucked up is that?” Later, in his Tough Rapper Guy heyday, he sees Schellenbach at a bodega but can’t bring himself to approach her: “I guess I didn’t say hi ’cause I was embarrassed thinkin’ about how much I’d changed.”

The absence of Yauch—perhaps the most adventurous and thoughtful of the Beastie Boys, who masterminded the Tibetan Freedom Concerts and declared that “the disrespect of women has got to be through” on a particularly memorable verse from 1994’s “Sure Shot”—is palpable both in print and on camera. Beastie Boys Book was remarkable for not really touching on that grief at all: “Too fucking sad to write about,” Horovitz demurred back then. But now he’s onstage, flashing back to Bonnaroo 2009; to hearing the enduring comfort of Al Green’s voice wafting from another stage; to the naivete of not realizing, there at the end, that it was the end. Horovitz chokes up; he lets the silence ring. “The rearview,” he tells us, “was nearly impossible to reposition.”

In their bandmate’s absence, all Diamond and Horovitz can do now is reposition the rearview: Beastie Boys Story is hopefully the last act in a pleasurable but awfully indulgent burst of multimedia brand management. They keep talking about their past mostly because they want us to know how much of it they regret, how much of it they’ve long since transcended. “It’s not so much that we settled down, it’s more like we settled in,” is how Horovitz puts it. “It’s not so much that we grew up, it’s more like we wised up.” Not the most memorable thing you’ve ever heard these guys say, no. But they won’t regret saying it, and you won’t regret watching them say it.